Issue

Issue #1Auteurs

François Hublet , Jean-Toussaint Battestini , Lucie Coatleven , Charlotte Kleine , Sofia Marini , Théophile Rospars

21x29,7cm - 102 pages Issue #1, September 2021 24,00€

Elections in Europe: December 2020 — May 2021

Introduction

The increasing interconnectedness of European politics requires a good knowledge of the political dynamics not only in the member states and their regions, but also beyond them, in the EU’s neighbourhood. In the constant flow of information and news, it becomes surprisingly easy to lose sight of the bigger picture. This first issue of BLUE therefore aims to provide the reader with a broad overview of the latest political developments, reporting on both macroscopic trends and smaller-scale dynamics, including at the local level.

Without sacrificing attention to detail, the contributions in this issue will therefore highlight the European issues at stake in the electoral events of the past six months. To facilitate comparison, a first part provides, in a concise manner, transnational elements that take up or extend the analyses contained in this volume: from participation figures to common themes (e.g. independence, the fight against corruption) and the impact of the Covid-19 pandemic, the main aspects of European politics over the past six months will be discussed.

With regard to national parliamentary elections, we start with the Romanian parliamentary election of December 2020, analysed by Ramona Bloj. This election, while leading to the formation of a centre-right government, also confirmed the position of the Social Democrats as the country’s largest party, and saw the emergence of a new right-wing formation. We then move on to the Dutch Lower House election of March 2021, covered by Simon Otjes’ contribution. It led to the renewal of the previous centre-right government. April saw parliamentary election in Bulgaria, reviewed by Dobrin Kanev, and in Albania, analysed by Ilir Kalemaj. Both elections saw a significant weakening of the position of the incumbent government parties vis-à-vis the opposition. In Bulgaria, a variety of new actors have emerged following the anti-corruption protests of last summer. Lastly, we discuss the parliamentary election in the Republic of Cyprus, which took place in May, and where all major parties lost ground to the radical right; it is presented by Vasiliki Triga and Gilles Bertrand.

Among the national elections, we also look at the Portuguese presidential election which happened in January, analysed by Eduardo Paz Ferreira. Despite the overwhelming victory of the conservative incumbent, the radical right came closer to the second-placed socialist candidate.

Other important elections were held at regional level in Spain, Germany and the United Kingdom. Martin Lepic and Robert Lineira discuss the unprecedented results of the Catalan election in February, marked by the demise of the liberal party and the parliamentary breakthrough of the radical right. Marius Minas and Oliver Drewes then comment the March elections in Rhineland-Palatinate and Baden-Württemberg, where the Social Democratic and Green Minister Presidents were largely reappointed. Finally, Fraser McMillan analyses the results of the Scottish election held in early May, where the dominance of the pro-independence forces reignited the debate on a new referendum. Finally, another particularly interesting election was contested in the Community of Madrid: the incumbent right-wing president gained a large majority, while the liberals disappeared; this election will be analysed by Francisco Cabezuelo.

Finally, the last section of this issue looks ahead to the important German elections at the end of September 2021. There, the reader will find the answers of the directors of the foundations of the three largest German parties, Martin Schulz (SPD), Norbert Lammert (CDU) and Ellen Ueberschär (Greens), to a series of questions posed by BLUE.

Evolution of the results of the European groups

In order to track the macroscopic developments and trends applicable to the whole of Europe, the analysis of aggregate data is essential. To analyse the dynamics of the different political families beyond their respective national contexts, we will rely on the affiliations to the groups in the European Parliament.

The final figures show an overall decline of the left and centrist forces, while the right-wing actors increased their share of the vote. However, the Greens and the radical right seem to contradict these general trends, with the former registering successes and the latter seemingly losing ground.

The radical left group GUE/NGL (European United Left/Nordic Green Left) experienced an overall decline (-6.23 pp on average), mainly due to poor performances in Portugal, Cyprus and the Netherlands, with a loss of 5.8, 3.3 and 2.45 points respectively. The mainstream left, embodied by the S&D group (Socialists and Democrats), was one of the most dwindling formations: it lost 12.13 points on average, with particularly large losses in Romania (-15.6 pp), Bulgaria (-14.47 pp) and Madrid (-10.51 pp), which were only partially compensated by results in Portugal (+7.98 pp), Catalonia (+9.3 pp) and Cyprus (+13.41 pp).

Parties affiliated with the Greens/EFA group in the European Parliament saw an overall increase (+8.3 pp), with particularly encouraging figures for Rhineland-Palatinate (+5.03 pp), and significant increases in Baden-Württemberg (+2.55 pp) and Madrid (+2.33 pp). In Bulgaria, the Greens also gained 4 seats in parliament, although this result is difficult to quantify in terms of vote share, as they ran in coalition with a right-wing party and other new formations (obtaining 9.45% of the total vote).

The centrist and liberal Renew Europe (RE) recorded moderate gains in most elections (between +2.41 pp in Rhineland-Palatinate and +5.07 pp in Baden-Württemberg), but poor performances in Catalonia (-19.84 pp) and Madrid (-16.08 pp) led to a negative balance of -13.8 pp. Therefore, they were the group with the largest variation in vote share in these recent elections.

The centre-right, embodied by the EPP (European People’s Party), increased its share of the vote by 8.45 pp on average. However, this overall figure hides some quite significant losses. For example, the centre-right lost 5 pp in the Netherlands and 4.14 pp in Rhineland-Palatinate, but also 11.68 pp in Bulgaria, against only a few important victories (+22.63 pp in Madrid and +8.7 pp in Portugal).

The conservative ECR group (European Conservatives and Reformists) seems to have benefited the most from the elections of the last months, with an upward trend in almost all elections (between +0.25 pp in Madrid and +11.9 pp in Portugal). The only exceptions to this trend are Bulgaria (-4.32 pp), Baden-Württemberg (-1.02 pp) and Cyprus (-25.97 pp).

Lastly, the radical right-wing group Identity and Democracy (ID) suffered slight declines (ranging from -2.25 pp in the Netherlands to -5.36 pp in Baden-Württemberg) wherever it participated in elections, with the exception of Bulgaria, where it increased by 2.37 pp. On average, it suffered a loss of 12.85 pp, among the most severe.

Some national parties still have no European affiliation. On average, with a gain of 11.22 pp, their share of the vote increased more than that of any of the European groups. Most of them are new players, often emerging after contests, as is the case for Bulgaria (+18.52 pp) and Cyprus (+11.9 pp) in particular.

Parties entering and exiting regional and national parliaments

The regional and national elections in the first half of 2021 were marked by the disappearance of some parties and the emergence of new ones. In Spain, the early regional elections in Catalonia and the Madrid region were devastating for Ciudadanos (RE). The liberal party, which had won the early regional elections in Catalonia in December 2017 with 25% of the vote and 36 seats, collapsed to 5.58% and won only 6 seats in the 14 February 2021 election. Worse, Ciudadanos disappeared from the Madrid assembly with only 3.6% of the vote in the May 2021 early elections compared to 19.5% in the 2019 elections. On the other hand, VOX (ECR) has anchored itself in the Spanish political landscape and won 7.67% of the votes in the early regional elections in Catalonia, entering the Catalan Parliament with 11 seats.

In Kosovo, where the vote took place on the same day as in Catalonia, the parliamentary elections resulted in the disappearance of the Democratic League of Kosovo (LDK, EPP) and Vakat (Bosniak minority interests) in favour of a centre-left party in support of the Union with Albania, Vetëvendosje. The SDU (Bosniak minority interests) and two parties defending the interests of the Roma minority are now represented in parliament.

In Liechtenstein, the Eurosceptic Democrats for Liechtenstein (DFL) replaced the other Eurosceptic party The Independents (DU) from which it had split. The Democrats won 2 seats and entered the parliament, while the Independents lost their 5 seats.

The early parliamentary elections in the Netherlands in March 2021 resulted in three new parties joining the House of Representatives. With 2.4%, the Pan-European federalist party Volt (Greens/EFA) and the JA21 (ECR), a split from the far-right party Forum voor Democratie (ECR) are represented by MPs each. The BBB, an agrarian party, won 1 seat and 1% of the vote.

The Rhineland-Palatinate Landtag election in March 2021 saw the Free Voters (FW, RE) enter the Landtag with 5.35% of the vote and 6 seats.

In Wales, the elections on 6 May were marked by the disappearance of the far-right and anti-devolution formations, UKIP (ID) and the Abolish the Welsh Assembly Party (AWAP, NI), which failed at getting re-elected to the Senedd with a score of around 1%.

Finally, in the Cypriot parliamentary elections on 30 May, the Democratic Front (DIPA, RE), a spin-off from the Democratic Party (DIKO, S&D), entered the House of Representatives with 4 seats.

No political parties entered or left the Scottish parliament or the Baden-Württemberg Landtag.

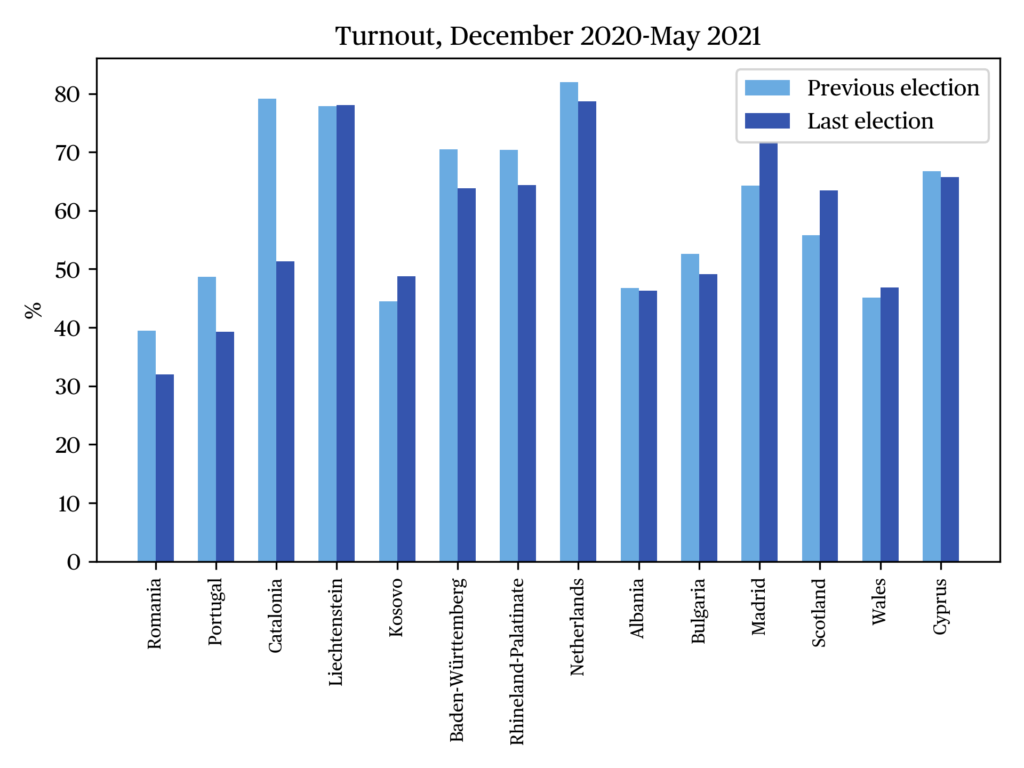

Participation and postal vote

Organising elections is a major challenge for the authorities in the context of the Covid-19 pandemic, since they are prone to a lack of social distancing. As a result, some elections have been postponed, such as the Calabria regional council election, which has been postponed to autumn 2021. However, despite the spread of the virus and thanks to the implementation of specific arrangements, a majority of these elections still took place. In most cases, postal voting was encouraged and standardised. Despite these arrangements, a drop in voter turnout was expected in view of the health context. However, this fear did not materialise everywhere — some countries such as Kosovo even recorded record turnouts, and elections where the stakes were perceived to be high were able to mobilise the electorate to a large extent.

The biggest drop in turnout was in Catalonia, down by 27.8 percentage points. Although this drop can be attributed in part to the pandemic, it is also explained by the reduced prominence of constitutional issues, which were one of the main stakes in the election. In contrast, three months later, the particularly high-profile and polarised election in Madrid saw a 7.47 point increase in turnout. Relatively large, though less dramatic, declines were also seen in Portugal and Romania, where turnout fell by 9.5 and 7.55 points respectively. It is worth noting that the Portuguese presidential election took place at a time when Portugal had one of the highest infection rates in the world and a nationwide lockdown was in place. Absentee voting was not allowed and the re-election of the incumbent, whose executive prerogatives are limited, appeared certain. In the end, although abstention in both Portugal and Romania reached the highest levels since the return of democracy in these two countries, the decline did not reach the proportions that had been feared.

More modest decreases in turnout, around 3 percentage points, were observed in the Netherlands (where almost 10% of the electorate voted by post) and in Bulgaria. In Germany, in the regional parliamentary elections in Rhineland-Palatinate and Baden-Württemberg, postal voting was highly successful, accounting for 65.9% and 51.31% of the votes respectively. However, the overall turnout decreased by 6 points in both Länder to 64%. Finally, in Cyprus and Albania, the ‘Covid effect’ did not seem to affect the turnout rate much, as it only decreased by 1.02 and 0.51 points respectively.

In contrast, in Kosovo, turnout increased by 4.2 percentage points compared to the last election. Similarly, Scotland recorded a significant increase in turnout (+7.69 pp) with a record turnout of 63.49%, the highest since the creation of the devolved Parliament in 1998. This was due in particular to the high profile of the independence debate — including the prospect of a new referendum — and the possibility of voting by post. Moreover, while some countries, such as Portugal, held elections when infetions rates were particularly high, it was relatively low in the United Kingdom on polling day on 5 May. Finally, the highest turnout was recorded in the parliamentary elections in Liechtenstein, where 77.82% of citizens voted, 97% of them by post — a voting method that was already widely used before the pandemic.

Interactions between elections

In three countries — the United Kingdom, Germany and Spain — several regional elections were held on the same day.

In the United Kingdom, elections to the devolved parliaments of Wales and Scotland were organised, while local elections also took place in England. In these the various parties in power were re-elected. While the Scottish National Party (SNP) maintained the same results as in 2016, Welsh Labour confirmed its dominance by winning almost an absolute majority (29 seats out of 60 in total). As for the results of the local elections in England, they confirmed the popularity of the Conservatives and their leader Boris Johnson: with 235 additional councillors (23% more than at the last elections), historic Labour strongholds, such as Hartlepool, passed to the Tories. Despite the UK-wide media coverage of the Scottish independence issue, it seems that the interaction between these different elections was ultimately quite modest. The results were mainly influenced by the electorates’ perceptions of the Covid-19 crisis management by the different regional governments. However, it was also noted that between 20 and 30% of Welsh people would support Welsh independence, a figure that is rising: the effect of the SNP’s success. The popularity of pro-independence ideas in Wales remains an open question.

Two regional elections in Rhineland-Palatinate and Baden-Württemberg kicked off Germany’s “super election year” (Superwahljahr). The results of these two Länder have therefore often been scrutinised as “weak signals” anticipating the outcome of the federal elections on 26 September. However, as the Länder are characterised by specific political cultures and very different socio-economic structures, it is difficult to make projections based on their results. Indeed, while the Social Democrats (SPD) scored very well in Rhineland-Palatinate (35.7%), the region where they are in power, they are in sharp decline nationwide where, according to the latest polls, they are only in third place behind the conservatives and the Greens. The very popular Baden-Württemberg Greens, the party of Minister President Winfried Kretschmann, campaigned on a more conservative and traditional line than the federal Greens and their list leader Annalena Baerbock. The regional effects of federal political dynamics are difficult to quantify: the so-called “masks affair” (a corruption case involving Christian Democrat parliamentarians) certainly affected the German public at large, but due to the widespread use of postal voting, many citizens had already voted when the scandal broke out.

Finally, although the constitutional issue has structured many Catalan elections in recent years, it seems that the health crisis has partly overshadowed it. Less expected, the relationship between the different levels of government was at the centre of the Madrid electoral campaign, which was a part of a frontal conflict between the regional Popular Party and Pedro Sánchez’s center-left national government, with the former opposing the government’s measures to control the pandemic and calling for regional “freedom”. However, the Catalan and Madrid elections are part of a wider Spanish dynamic. The collapse of the liberal unionists of Ciudadanos (RE) and the growing polarisation of the political space (along the right-left and pro-independence-unionist axes) are the main trends. Significant network effects are unfolding: the Madrid election was provoked by the reversal of alliances caused by Ciudadanos in the Murcia parliament; Pablo Iglesias, a historical figure of Podemos, resigned from the Spanish government to lead his party’s campaign in Madrid, retiring from politics after his defeat.

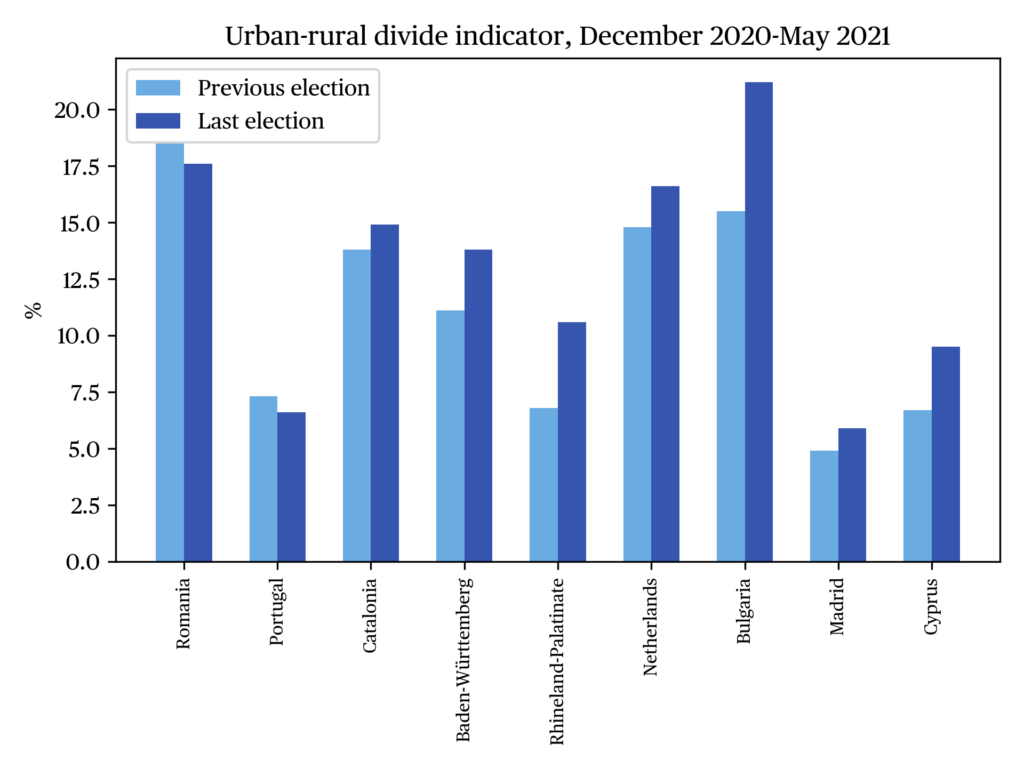

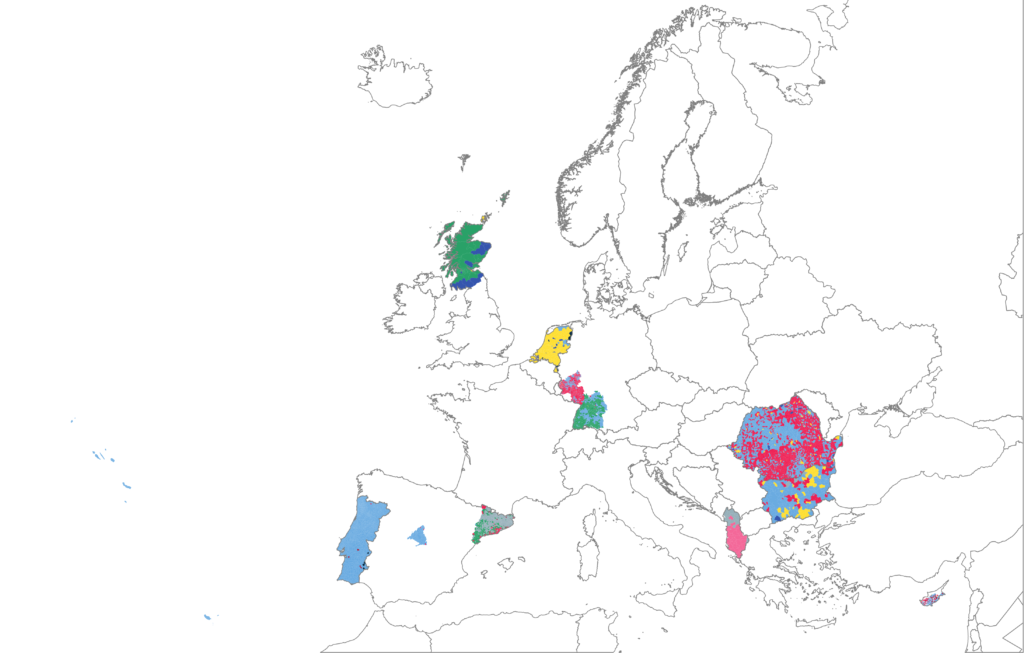

Urban-rural divide

BLUE has constructed an indicator to measure the polarisation of the vote between urban and rural areas in the elections presented in this issue. Given the aggregate score u1, …, up of the parties in the urban electorate and the aggregate scores r1, …, rp of these same parties in the rural electorate (in percent), we consider

1/2 ( |r1 – u1| + … + |rp – up| )

The result is a percentage that varies between 0% and 100%, where 0% means that the shares of the different parties in the urban and rural electorates are identical, and 100% means that the urban electorate votes for entirely different parties than the rural electorate.

The first observation that can be made is that the urban-rural divide was most pronounced in Bulgaria and Romania, where 21.2% and 17.6% respectively of urban voters voted differently from rural voters. This difference is up by 5.7 percentage points in Bulgaria, compared to a marginal decrease of 1 percentage point in Romania.

In Portugal, the presidential election in January saw the hugely popular Social Democratic Party (PSD, EPP) candidate win with 60.7% of the vote. Not surprisingly, due to his large victory, our indicator is only 6.6%. In other words, only 6.6% of urban voters voted differently from rural voters, down 0.7% from the 2016 presidential election. The high popularity of the candidate in both rural and urban areas strongly reduces the value of the indicator. A similar reasoning can be applied to the early regional elections to the Madrid Assembly, where the Popular Party (PP, EPP) candidate came out in the lead in a vast majority of municipalities.

In Catalonia, the split between urban and rural voters increased slightly between the 2017 and 2021 regional elections, from 13.8% to 14.9%. This result can be partly explained by the fact that rural areas (except for Val d’Aran) are more likely to vote for pro-independence parties than Barcelona, which tends to vote for anti-independence parties such as PSOE or Ciudadanos.

The regional elections in Baden-Württemberg and Rhineland-Palatinate highlighted an intensification of the urban/rural divide. The difference between the urban and rural vote increased by 2.8% and 3.8% respectively. Thus, 13.8% of urban voters cast a different vote from rural voters in Baden-Württemberg and 10.6% in Rhineland-Palatinate. In sum, in most cases where elections were held between December 2020 and May 2021, the urban-rural divide increased moderately. Only Romania and Portugal registered a decrease in this divide.

Socio-economic determinants of the vote

Table c presents the result of the estimation of a least squares model evaluating the effect of eight socio-economic factors on the electoral shares of the different European political groups, aggregated at NUTS 3 level.

| Group | Positive effect | Negative effect | R² |

| GUE/NGL | Birth rate* median age* | 0.85 | |

| Greens/EFA | Univ. degree* GDP/capita PPP* | Pop. dens.*** net migr. *** median age* | 0.76 |

| S&D | Pop. dens.* | Birth rate* GDP/capita PPP* univ. degree* | 0.58 |

| RE | Net migr.* birth rate* median age* pop. dens.** | Univ. degree* | 0.79 |

| EPP | Univ. degree** GDP growth** | Pop. dens. | 0.75 |

| ECR | Univ. degree** | 0.81 | |

| ID | Median age*** | 0.82 |

Controls: member states, source: Eurostat, last available year

Parties considered close to a group have been counted together with this group.

221 NUTS 3 regions: 28 BG, 1 CY, 80 DE, 5 ES, 40 NL, 25 PT, 42 RO.

c • Results of the statistical model at NUTS 3 level

All other things being equal, population density has a positive effect on the electoral share of the Social Democrat and Liberal groups, and a negative effect on that of the Greens/EFA (whose regionalist component played an important role in this term) and the European People’s Party. Conversely, the proportion of the population with a university degree has a positive effect on the electoral share of the Greens/EFA and the European People’s Party, and a negative effect on that of the Social Democrats and the ECR. The demographic situation has a significant effect for five out of seven groups: an older population tends to increase the share of the Liberals and the far right (ID) and to reduce the share of the radical left and the Greens/EFA.Liberals also benefit from a positive net migration rate and a higher birth rate, while left and centre-left groups perform better in areas with a negative migration rate (Greens/EFA) and a low birth rate (GUE/NGL and S&D). Perhaps more surprisingly, the effect of economic factors appears to be smaller: unemployment is not significant for any group at the 90% confidence level, the level of GDP per capita favours the Greens/EFA and disfavours the S&D, but has no effect on the scores of the other parties, and GDP growth has a significant (and positive, at the 95% confidence level) effect only on the scores of the European People’s Party.

Autonomy — independence

The issue of regional autonomy and independence played a key role in some of the elections in the first half of 2021. In Catalonia, regional elections were held in February following the dismissal by the Supreme Court for “disobedience” of the President of the Generalitat Quim Torra. This decision, accepted by the left-wing pro-independence party Esquerra Republicana de Catalunya (ERC), led to a split between the pro-independence ERC and Junts per Catalunya (JxCat) and precipitated the regional elections. As in every election since 2015, when the Junts pel Sí coalition in favour of the region’s immediate independence from Spain won the elections, the issue of Catalan independence has dominated the debate. Despite the low turnout of Catalans at the polls (51.29% compared to 79.09% in 2017), the pro-independence parties still obtained an absolute majority in seats with 74 out of 135. For the first time since the establishment of the Generalitat in 1979, the sum of the votes of the pro-independence parties reached the absolute majority of the votes cast, i.e. 50.73% of the ballots cast, which constitutes a symbolic victory for the Catalan pro-independence parties versus the Spanish state.

Similar issues marked the Scottish elections. The Scottish National Party (SNP), the main pro-independence force, pushed ahead with a campaign that claimed their re-election would lead to a second independence referendum. The Scottish Green Party also campaigned in favour of independence as they did in the first Scottish independence referendum in 2015. The SNP won 64 out of 129 seats, one seat short of an absolute majority. The sum of the seats of the pro-independence parties SNP and Scottish Green Party is 72, guaranteeing an absolute majority for the pro-independence cause in the Scottish Parliament. Here too, the British Prime Minister Boris Johnson ruled out the organisation of a new referendum on self-determination for Scotland on the evening of the elections.

In Wales, the pro-independence momentum that Plaid Cymru had hoped for did not materialise. The party achieved the same score in the May elections as in 2016, 20%, but made progress by gaining an extra seat, from 12 to 13 of the 60 seats in the Welsh Parliament.

In Romania, the Magyar Democratic Union of Romania, a historic party defending the interests of the Hungarian minority in Romania and the autonomy of the Szekler country, scored 5.74%, down 0.5 percentage points, but retained the same number of deputies and senators as in the previous legislature, i.e. 21 deputies and 9 senators. The Movement for Rights and Freedoms, defender of the interests of the Turkish minority in Bulgaria, which represents almost 10% of the country’s population, obtained 10.73%, up one point compared to 2017, and obtained 30 seats out of 240.

Anti-corruption movements

In the three elections held in Eastern Europe (parliamentary elections in Albania, Romania and Bulgaria) the fight against corruption was a central issue.

Past years have been marked by mobilisations against the corruption of the respective ruling parties. For example, the Rezist civil society movement led to the resignation of the Romanian social democratic government (Social Democratic Party, PES) in November 2019, paving the way for a centre-right minority government (National Liberal Party, EPP) after two years of massive protests. In Albania, the protests were initiated by the Democratic Party (EPP), starting in February 2019, against the backdrop of a boycott of local and parliamentary elections by opposition parties. This boycott followed the publication of audio recordings by the newspaper BILD proving the involvement of Prime Minister Edi Rama and his party (Socialist Party, associated with the PES) in vote-buying campaigns and intimidation of opponents. Finally, in Bulgaria demonstrations took place following an investigation by Radio Free Europe (RFE/RL) implicating members of Boyko Borisov’s centre-right government (GERB, EPP, in coalition with the United Patriots, ECR) as well as magistrates. This led to a major political crisis, supported by President Rumen Radev (Ind.), which continued until election day.

Although the context was similar, the electoral consequences of this dynamic were different. In Romania, the anti-corruption vote largely benefited the USR-PLUS (RE) alliance, which has its roots in the civil society and the 2015 anti-government protests, and saw its score rise from 8.9% to 15.6%, entering government alongside the liberal-conservative PNL (EPP) and the Hungarian minority party (UDMR, EPP). In Albania, the anti-corruption movement failed to challenge the institutional and political hegemony of the Socialist Party, which retained its majority (49 % of the vote, 53 % of the seats in parliament). However, the opposition unified under the Democratic Party and its leader, Luzim Basha, who gained 10 percentage points, almost reaching 40% of the votes cast. In Bulgaria, the right-wing governing coalition collapsed in favour of three anti-corruption forces. The new ITN party entered parliament in second place with 17 % of the vote, the new anti-corruption movement ISMV received 4.6 % of the vote, while the centre-right alliance Democratic Bulgaria (EPP/Greens) obtained 9 %. The ruling GERB lost 7 points (to 26%), having alienated part of its electorate — the party had itself been created to fight corruption. The socialist BSP ( PES), despite having supported the protests, lost 12% of its votes to the two new anti-corruption forces, stabilising at 14.5%. The three new parties, although big winners, failed to organise a governing coalition, paving the way for new elections in July.

Ideologically, all the anti-corruption parties in Eastern Europe are characterised by their Europhilia, or at times even their Euro-Atlanticism, with integration into Western organisations seen as a means of continuing the fight against a traditional national political class deemed corrupt and regularly supported by Russia.

Role of the diaspora

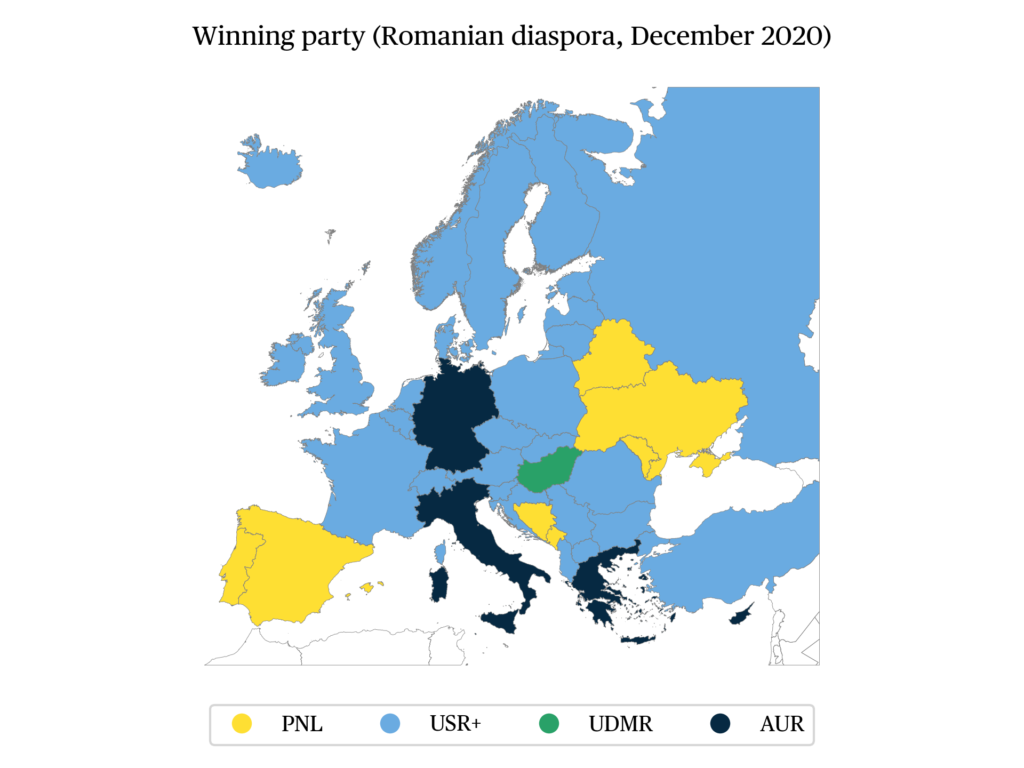

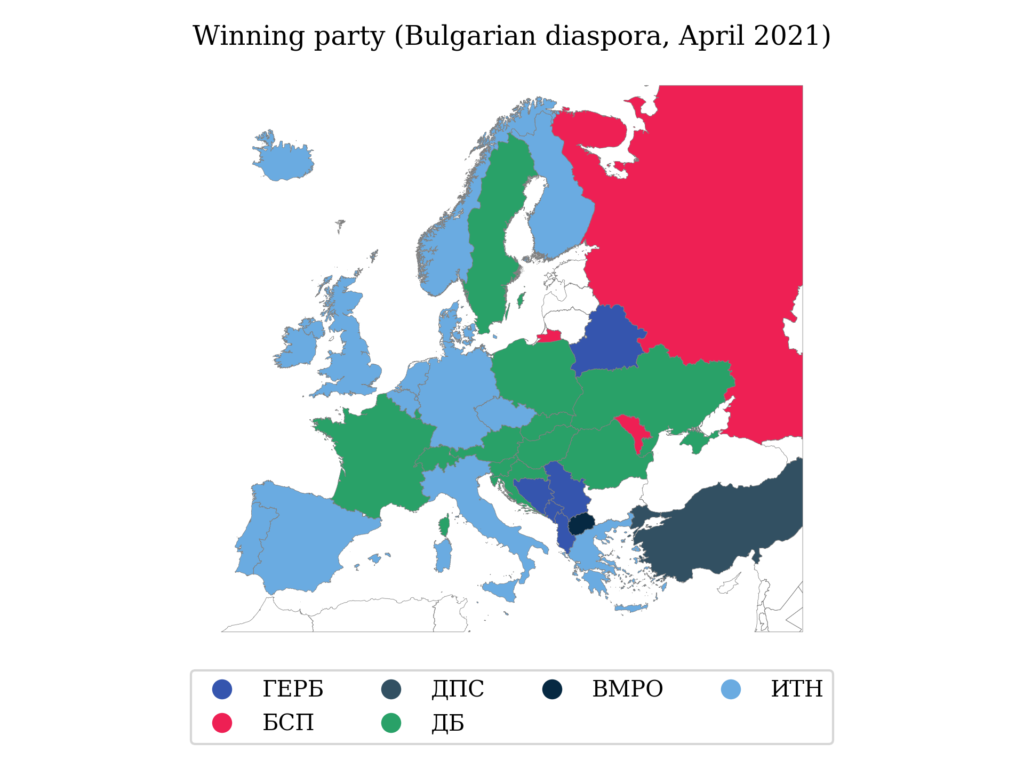

For five elections : the Bulgarian, Romanian, Cypriot and Catalan parliamentary elections, as well as the Portuguese presidential election, the data on diaspora voting was published.

Representing respectively 5% and 4% of the citizens who went to the polls, the large Bulgarian and Romanian diasporas voted more for the perceived ‘new’ parties, be they anti-corruption centrists or national-conservatives, than the average non-diaspora voter. In Romania, for example, the Social Democratic Party (S&D), which came first nationally with 28.90% of the vote, won only 3.37% of the vote among voters living abroad. The USR-PLUS alliance (RE, anti-corruption), which obtained 15.37% of the votes at the national level, won 32.59% of the diaspora votes; the young nationalist party Alliance for the Union of Romanians (AUR, ECR), whose total score was 9.08%, won 23.24% of the diaspora voters. In four EU Member States (Germany, Italy, Greece, Cyprus), the AUR came first. Its success in Germany and Italy, where almost half of the voters from the EU come from, and where the party won around 35% of the vote, contrasts with the scores much closer to the Romanian average in France and Spain, where the USR-PLUS won over the AUR by 5 to 10 points. The AUR, which is in favour of the union of the Republic of Moldova with Romania and is also present in this country, was not particularly successful among the Romanians in Moldova: the party only received 8.81% of the vote.

In a similar pattern, the Citizens for the Development of Bulgaria (GERB, EPP), the conservative party of the outgoing Bulgarian prime minister, received only 8.57% of the diaspora vote, compared to 25.80% at national level. Similarly, the left-wing alliance formed around the Socialist Party of Bulgaria (BSP, S&D) obtained only 6.46%, compared to 14.79% nationwide. In contrast, the centrist anti-corruption party “There Is Such A People” (ITN) received 30.45% of the diaspora vote compared to only 17.40% nationally, while the centrist Democratic Bulgaria coalition received 17.40%, again almost double its national score of 9.31%. One of these two parties came out on top in each of the EU states. Finally, the four main nationalist or far-right lists received 14.69% of the diaspora vote, compared to 11.25% nationally. The nationalist party IMRO (ECR), which advocates a rapprochement between Northern Macedonia and Bulgaria, obtained almost 40% of the vote in that country.

In both cases, the diasporas appear to be more receptive to anti-corruption rhetoric, but also more likely to support nationalist formations. The traditional centre-left and centre-right governing parties (with the notable exception of the Romanian PNL) now carter to only a very small fraction of citizens living abroad.

The diaspora’s tendency to support “alternative” candidates is also present, albeit to a lesser extent, in Portugal and Catalonia. Incumbent Portuguese president Marcelo Rebelo de Sousa (PSD, EPP), elected with 60.67% of the vote, won only 52.65% of the diaspora vote, and did not obtain an absolute majority of votes (46.03%) among Portuguese living in the EU. Ana Gomes, an independent centre-left candidate, won 18.51% of the diaspora vote (23.50% in the EU), compared to 12.96% at national level. The candidate of the new party Iniciativa Liberal (IL, RE) won 5.61% of the Portuguese abroad vote, compared to only 3.23% nationally, while the far-right and radical left candidates also improved their scores slightly. However, the significance of this analysis is limited by a very low level of participation: out of 1.5 million registered Portuguese abroad, only less than 30,000 (2%) turned out to vote.

In Catalonia, where the turnout of the diaspora is also very low (4%), its electoral behaviour is characterised by a slightly higher support for pro-independence parties than the regional average (54.87% against 50.77%). The scores of Vox (ID), the Socialist Party of Catalonia (PSC, S&D) and the Republican Left of Catalonia (ERC, Greens/EFA) are lower, those of JxCat (pro-independence, NI) of the radical left and Ciutadans/Ciudadanos (RE) higher than at the regional level.

Religious cleavages and political culture

Religion remains a significant factor in several of the polls studied.

In Rhineland-Palatinate, a North-South divide in voting behaviour was identified, which corresponds to the historical religious divide in the state. Thus the CDU (EPP), the offspring of the Catholic Zentrum party, has retained a significant electoral base in the Catholic north (Rhineland), while the SPD (S&D) retains a majority in most constituencies of the Protestant Palatinate. At the same time, the Free Voters (FW, RE) outperformed in predominantly Catholic areas, while the AfD (ID) saw its electorate concentrated in traditionally Protestant constituencies.

An equivalent pattern could be observed in Baden-Württemberg, where the Catholic regions in the south (Swabia and Baden) voted more than elsewhere for the CDU, and Protestant Württemberg, where the SPD had above-average results. Here, the other parties, and in particular the Greens, the big winners of the election, did not have a territorial division of their electorate coinciding with the religious map.

Although a North-South religious divide exists in the Netherlands between Protestants and Catholics, this did not translate into a significant differentiation in voting on this criterion. Only in the Bijbelgordel (the Dutch ‘Bible Belt’) in the centre of the country, marked by its very strong Calvinist conservatism, do the SGP (the Reformed Political Party, ECR) and the Christian Union (UC, EPP) enjoy significantly higher than average scores. The idiosyncrasies of the Christian parties in these regions remain very strong.

In other elections, notably in Romania and Bulgaria, the relation between party performance and the religious distribution of the population is mainly explained by the ethnic vote. The Bulgarian Movement for Rights and Freedoms ( RE ) has its electorate concentrated in areas with an over-representation of Islam, i.e. territories with strong Turkish ethnic minority communities. The Romanian UDMR (EPP) has its best results in areas with a Roman Catholic majority, i.e. departments in which the Hungarian minority is in the majority, while the parties reputedly close to the Romanian Orthodox Church (BOR) score much lower than their national averages, whether they are left-wing conservatives (PSD, PES) or populist and eurosceptic (AUR, ECR).

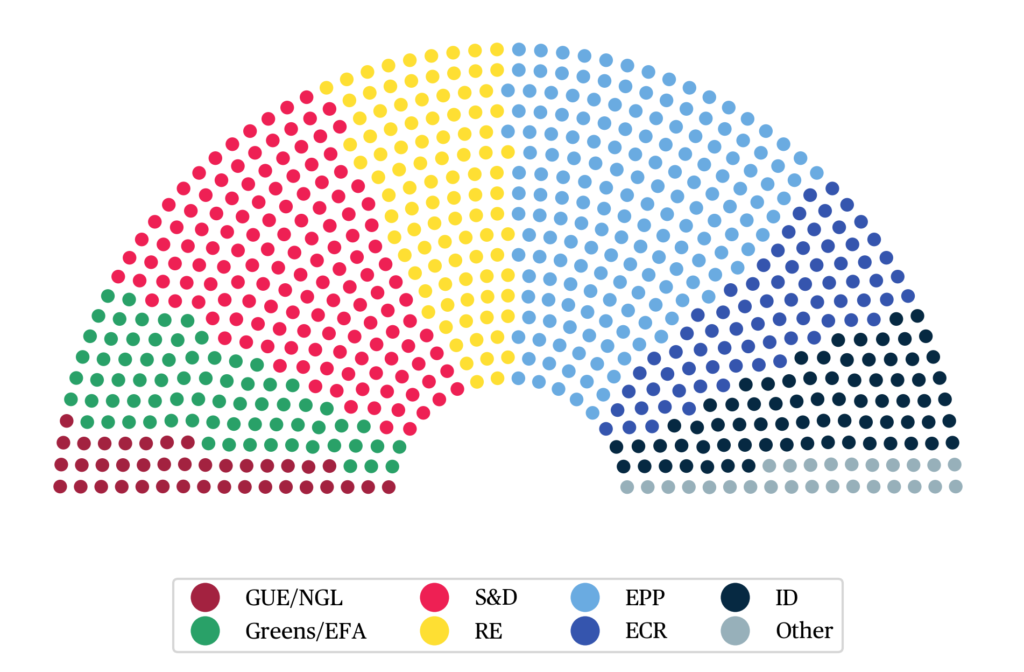

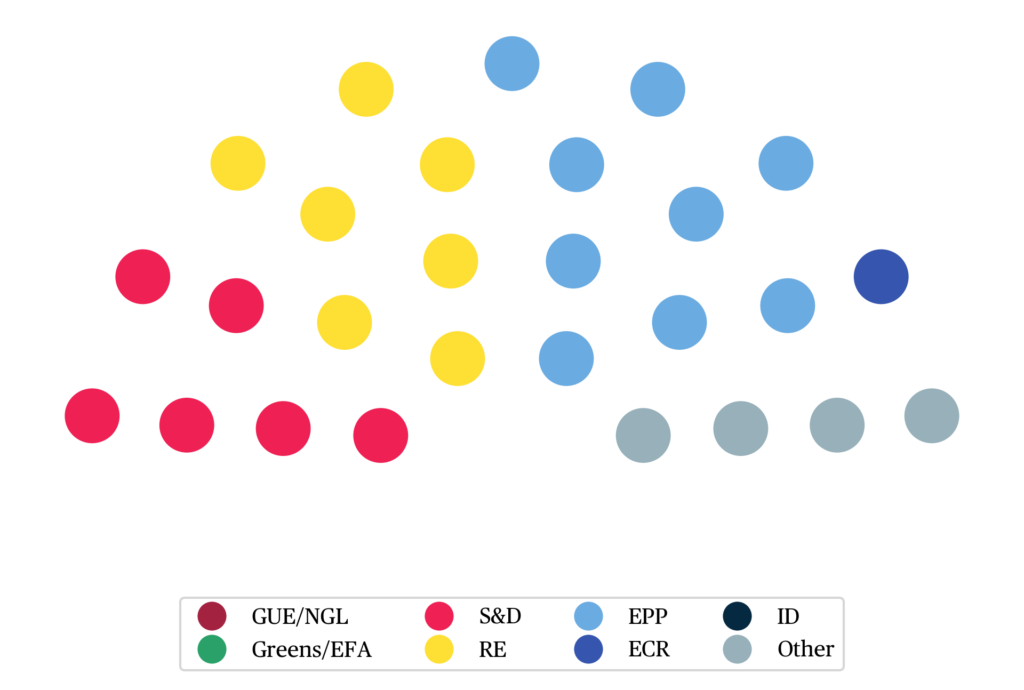

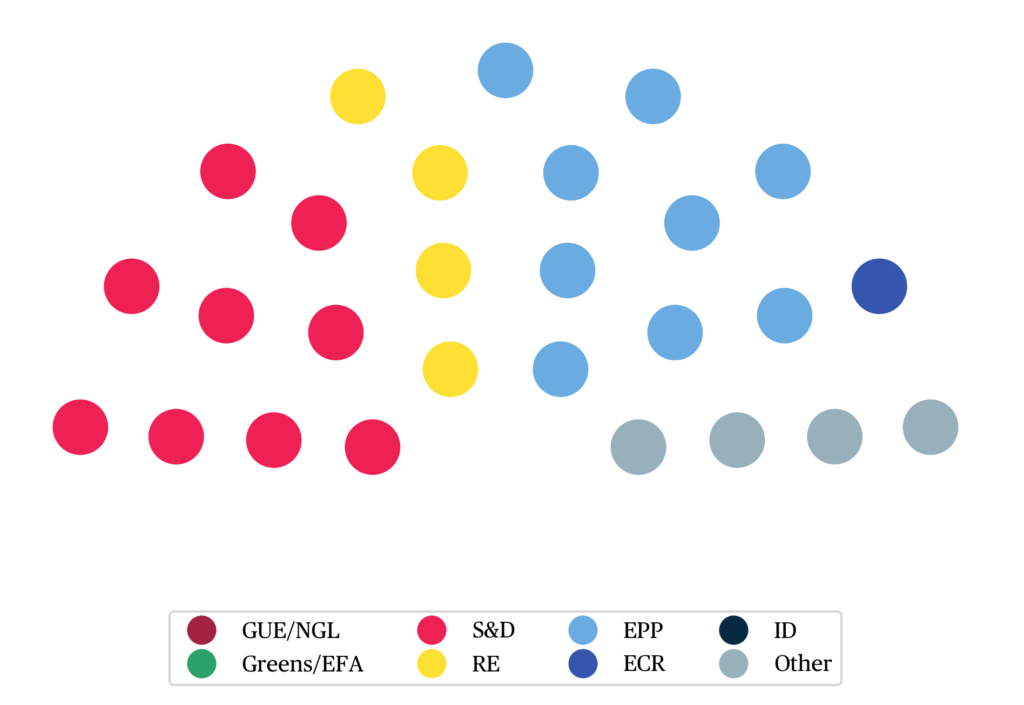

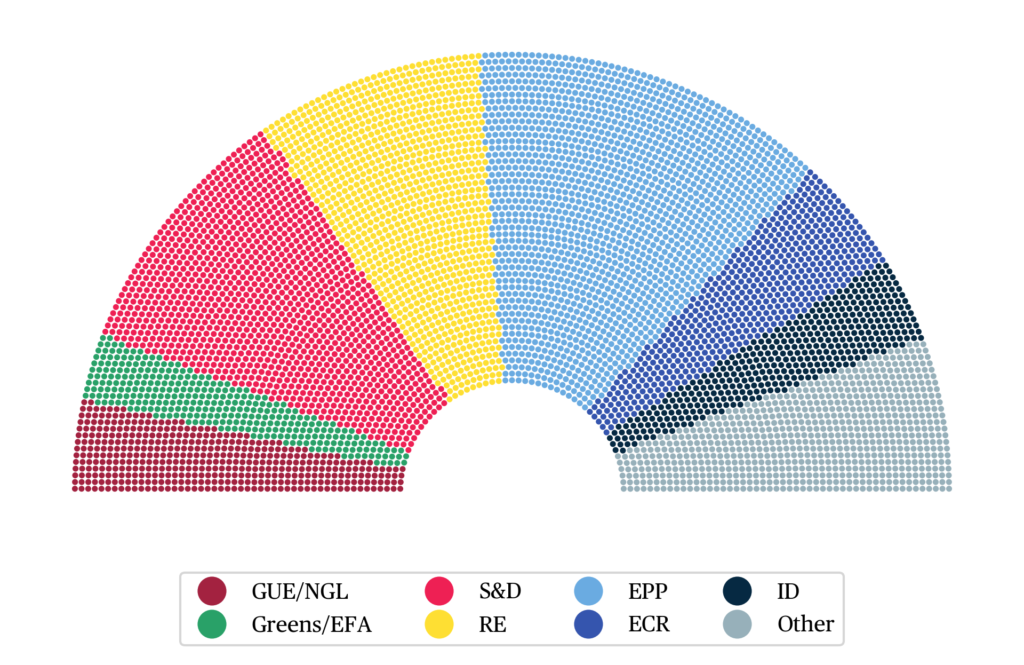

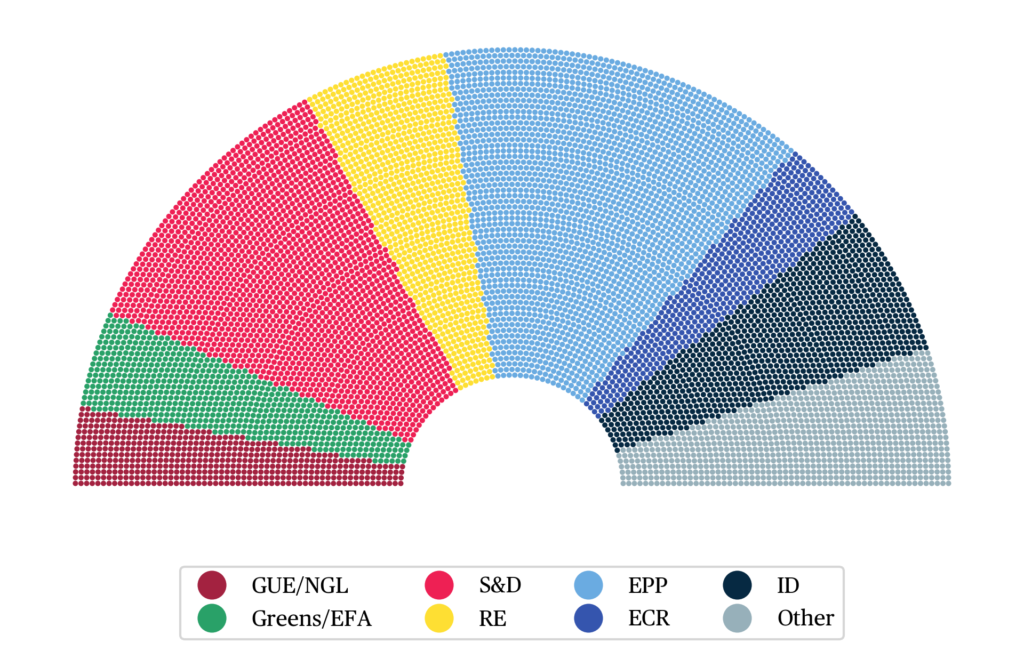

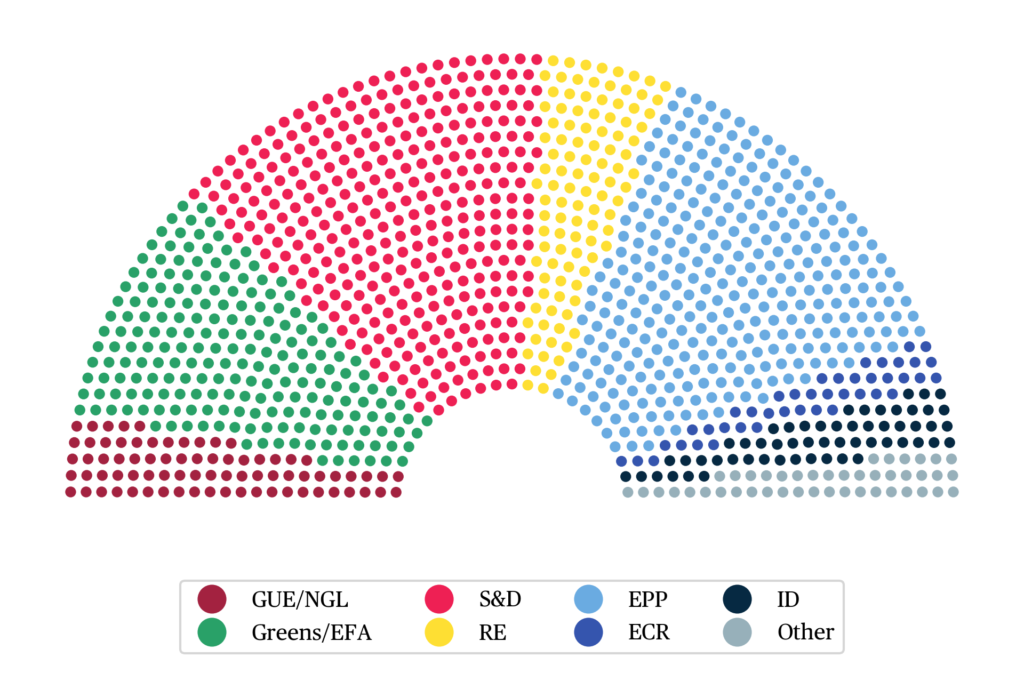

Seat shares of European political families, June 2021

The European Parliament

The European Council

The European Commission

Member states’ parliaments

Regional parliaments

City councils of the EU’s 15 cities with over one million inhabitants (« M15 »)

The Continental Map

citer l'article

François Hublet, Jean-Toussaint Battestini, Lucie Coatleven, Charlotte Kleine, Sofia Marini, Théophile Rospars, The Continental Review, Sep 2021, 7-19.

à lire dans cette issue

voir toute la revue