Issue

Issue #3Auteurs

François Hublet , Jean-Toussaint Battestini , Lucie Coatleven , Jean Cotte , Charlotte Kleine , Mattéo Lanoë

Issue 3, March 2023

Elections in Europe: 2022

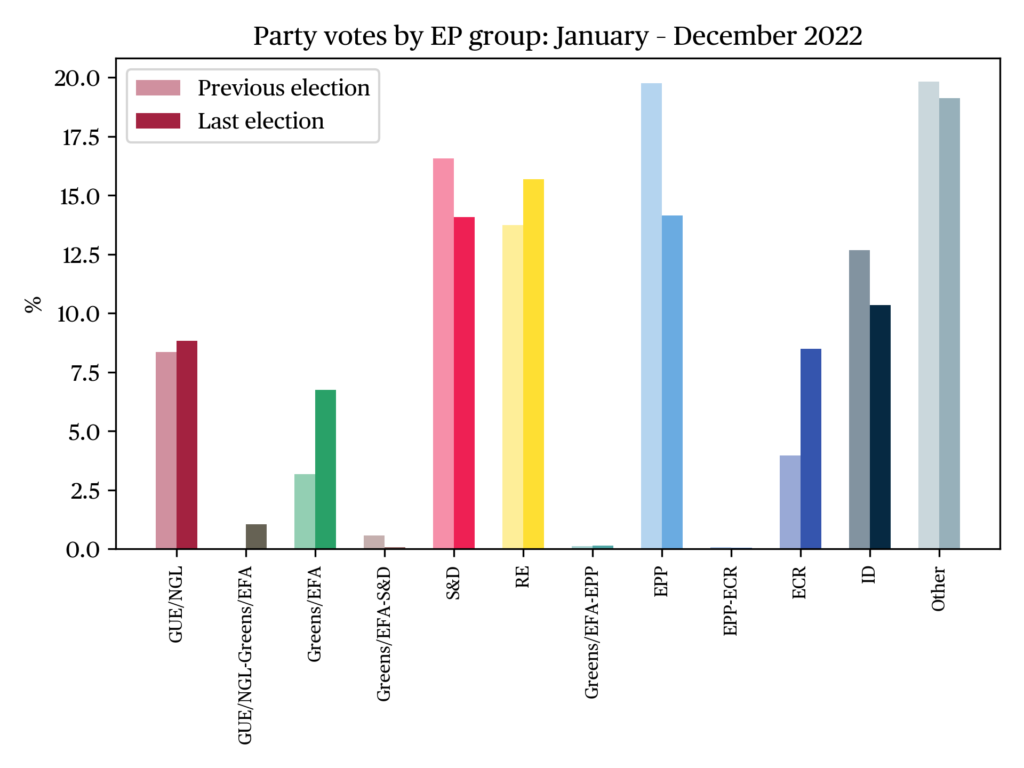

Evolution of the results of European groups

We open this summary with an analysis of the evolution of the balance of power between the different European political families in 2022. For this purpose, as in previous issues of BLUE, the results of national and regional parties are aggregated according to their groups in the European Parliament. 1

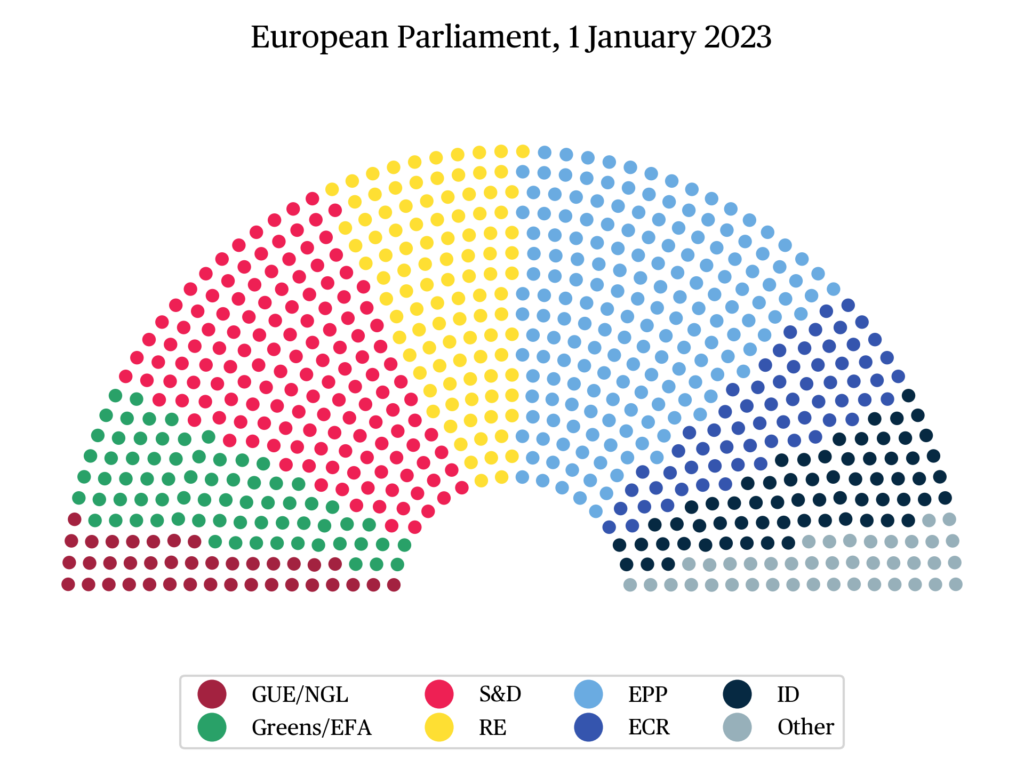

Overall, this year has seen a weakening of the traditional center-left (S&D) and center-right (EPP) groups, while the Greens and regionalists (Greens/EFA), and the neonationalist right (ECR) gained votes. The tradical left (GUE/NGL) experienced a downward trend in many regions — with the notable exception of France —, while the historical group of the European far-right (ID) suffered important overall losses.

In most ballots, the radical left parties in the GUE/NGL group are losing ground, confirming the negative trends of the previous year. The sharpest declines were observed in Saarland (-8 pp), where Die Linke seems to have lost its historical bulwark, Portugal (-5.5 pp), and Slovenia (-4.9 pp). Only the French presidential elections saw a rebound, despite scattered candidacies, making for a sightly positive overall trend (+0,5 pp); the group saw a gain of 4.3 pp in the first round, but was unable to qualify a candidate to the second round. In the French general elections, the LFI (GUE/NGL) party took the lead in the electoral alliance New Popular, Ecological and Social Union (NUPES) coming in second place in the second round, a gain of 19.73 pp compared to the results of PCF (GUE/NGL), LFI (GUE/NGL), PS (S&D) and EELV (Greens/EFA) in 2017.

The Green and regionalist parties in the Greens/EFA group are up for the third consecutive quarter, with an average gain of 3.6 pp. Gaining ground in all elections in which they were present except in Portugal (-1.9 pp), Hungary (where the LMP party ran in a coalition, making it impossible to assess its individual performance) and the Austrian state of Tyrol, the Greens experienced strong growth in North Rhine-Westphalia (+11.76 pp), Schleswig-Holstein (+7.94 pp), Lower Saxony (+6,33 pp) and France (+4.63 pp). The Green president of Austria, Alexander Van der Bellen, was reelected in the first round of voting in a landslide victory (56,7%).

After six months of relative stability, the Social Democratic S&D group again suffered significant losses, averaging 2.5 pp. The group’s vote share went down in Latvia (-15 pp), Schleswig-Holstein (-11.6 pp), France (-4.6 pp), Castilla y León (-4.9 pp), and North Rhine-Westphalia (-4.6 pp). The Social Democrats, however, had three spectacular victories — each time gaining an absolute majority — in Portugal (+4.3 pp), Malta (+0.1 pp), and Saarland (+13.9 pp), three historical S&D strongholds. They consolidated their majority in Denmark in the snap elections, giving the outgoing minority government a (theoretical) outright majority (+1.6 pp).

Despite significant losses in some regions, the liberal-centrists of the Renew Europe (RE) group gain 1,9 pp on average. Defeats in Andalusia (-15,2 pp), Denmark (-15 pp), Castilla y León (-10.6 pp), Latvia (-7 pp), North Rhine-Westphalia (-6.4 pp) and Schleswig-Holstein (-4.9 pp) are outset by more modest successes, albeit in larger electoral contests, in France (+3.8 pp in the presidential election in April, but with incumbent Macron obtaining only a minority government after the June parliamentary elections), Portugal (+3.9 pp) and Saarland (+2.8 pp), and only one clear victory, that of Robert Golob’s Freedom movement in Slovenia (+13.9 pp for all RE-affiliated parties). Hence, this good overall performance, which newly places RE ahead of all other groups with 15,7% of the vote, is more fragile than what vote figures suggest. When considering only parliamentary and regional elections, the RE group suffers a net loss of seats.

The European People’s Party (EPP) has experienced major setbacks, losing 5,6 pp on average. Apart from the reelection of the conservative Latvian government (+12,45 pp), their only victories were in local elections, first in Andalusia (+22,5 pp), and later in the German Länder of North Rhine-Westphalia (+3.0 pp) and Schleswig-Holstein (+10.0 pp), where incumbent Minister-President Daniel Günther saw his popularity confirmed. All other elections resulted in losses, some of them severe: in France (-15.2 pp), Saarland (-12.1 pp), Slovenia (-4.4 pp), Portugal (-2.1 pp) and Malta (-1.9 pp), the electoral weight of traditional right-wing parties declined.

Despite competing in only 8 elections in BLUE’s main program, the national-conservative ECR group was by far the biggest winner of this electoral year, with +4.5 pp on average. The neonationalists within the ECR celebrated a series of major successes with Fratelli d’Italia’s victory at the general election (+20,7 pp), the second place of the Sweden Democrats (+15,1 pp), the victory of the FI/Lega/FdI coalition in Sicily, and the good results of Vox in Castilla y León (+12.3 pp). Giorgia Meloni (FdI) now leads the Italian government, while in Sicily, Castilla y León and Sweden, an ECR member party is part of the parliamentary majority in a coalition with the center-right.

The far-right ID group continues its decline (-2.3 pp). Despite significant gains in Portugal (+6.0 pp), France (+1.9 pp in the first round of the presidential elections, 7.7 pp in the second, +5,6 pp in the first round of the general election, +8,5 pp in the second), in the Austrian state of Tyrol (+3,3 pp) and the German state of Lower Saxony (+4,8 pp) at the expense of the traditional center-right, the group has faced hard setbacks. They declined in the three other German Länder that voted this year (from -0.5 to -2.0 pp), in the Austrian presidential election (-17,3 pp), in the Italian general election (-9,2 pp) and the Danish general election (-6,1 pp).

Non-affiliated parties and cross-group coalitions lost slightly (-0.7 pp), but their vote share remains higher than that of any EP group. Outside of Hungary, the Danish general election saw the strongest increase in the vote share of non-affiliated parties (+23 pp), via the appearance of two new parties in June 2022: the Moderates, a split from the Liberal Party, which came in third place, and the Danish Democrats, a split from the Danish People’s Party, which came in fifth place. These two new parties, if they join a European group, would be close to the positions of RE and the EPP respectively. Owing to the presence of ultranationalist candidate Éric Zemmour, the French presidential election also saw a strong increase in the score of non-affiliated parties (+7.8 pp).

Parties entering and exiting regional and national parliaments

With the exception of those in North Rhine-Westphalia, Malta, Sicily, Sweden and Tyrol, all parliamentary elections in the first semester of 2022 saw parties entering or leaving the respective regional or national legislatures.

Slovenia was the country with the most party upheaval. Between the elections of 2022 and 2018, nine new parties from the centre, the right, the environmental movement and also a conspiracy-inspired party in reaction to the anti-covid19 policy competed in the general elections. Only the Movement for Freedom, which brought together a large coalition of centrist parties, made it into parliament by winning the elections against the outgoing right-wing Prime Minister, Janez Janša, who was accused of undermining the rule of law and press freedom in the country. The Slovenian Pensioners’ Interest Party left parliament, dropping from around 5% to less than 1%, which was not enough to remain in the Slovenian parliament.

In Latvia, the parliamentary elections saw the entry of three parties and the exit of four others. The Russian minority and Eurosceptic party For Stability, founded in 2021, entered parliament with 11 seats and a score of 6.9%. The right-wing populist party Latvia First, founded in 2021, also entered parliament with 9 seats (6.3%). The Progressives (Greens), who had failed to win a seat in the 2018 elections manage to enter parliament with 6.2% of the vote (10 seats). The Conservatives (-16 seats), Harmony (S&D, Russian minority interests, -23 seats), For Development (RE, centrism, -13 seats) and For a Humane Latvia (populist right, -16 seats) all lost representation in the Latvian parliament, failing to reach the 5% mark.

In the French National Assembly, the NUPES coalition enabled Europe Écologie Les Verts (EELV) to obtain 23 seats, allowing it to make a comeback in the National Assembly after a gap between 2017 and 2022 when there was no group representing this party. While the National Rally (far right) already had just under 10 seats between 2017 and 2022, the breakthrough in June 2022 allows the party to be fully represented in the National Assembly and to have a group.

In Bulgaria, where a general election was held for the fourth time in 18 months, the anti-corruption party There is such a people, founded in 2020 with the aim of fighting corruption and which had previously finished second in the April 2021 general elections (17.4% of the vote, 51 seats), then 1st in the July 2021 early elections (24.1%, 65 seats), only to fall to 5th place in November 2021 (9.4%, 25 seats), obtained only 3.7% of the vote, losing all of their seats in parliament. The national-conservative party Bulgarian Awakening, founded in May 2022 by former Prime Minister Stefan Yanev, entered parliament with 12 seats and 4.5% of the vote.

In Hungary, the far-right party Our Homeland, founded by dissidents of Jobbik, a former ultranationalist party but which has made its aggiornamento towards the conservative right, and which then guided the coalition of the United Opposition against Viktor Orban, entered the Hungarian Parliament winning 6 seats.

In Portugal, where early elections were held following the collapse of the left-wing coalition, the center-right Popular Party, which held 5 seats, lost its representation in the Portuguese Parliament, dropping from just under 5% to 1.60%.

Italy’s early general election on September 25 saw the regionalist and populist party Sud chiama Nord (“South Calls North”), founded in 2022 by former Messina mayor Cateno de Luca, win one seat in the Italian Chamber of Deputies and one in the Senate. The centrist “Third pole” coalition Azione-Italia Viva (RE), an alliance between Carlo Calenda’s Action Party and Matteo Renzi’s Italia Viva, confirms its presence in the Chamber of Deputies (21 seats) and the Senate (9 seats).

Following the snap elections held in November, two parties are newly present in the Danish parliament: the Moderates (liberalism, centre-right) with 16 seats (9.3%) and the Danish Democrats (populist right, euroscepticism) with 14 seats (7.9%).

Ciudadanos (center-right) continues its process of disappearance from the Spanish political scene, but manages to save a meager representation in the regional parliament of Castilla y León, going down from 12 seats to 1. In Andulasia, Ciudadanos loses all of its 21 seats after obtaining only 3% of the vote, compared to 18.3% in the 2018 regional elections The movement for the defense of the interests of rural Spain, “Empty Spain,” obtained 3 seats and entered the regional parliament of Castilla y León.

Finally, in Schleswig-Holstein, the far-right Alternative for Germany (AFD) party leaves the regional parliament, losing its 5 seats acquired in the 2017 elections. In Lower Saxony, the FDP (RE) left the regional parliament by failing to pass the 5% threshold, losing the 11 seats it held.

Outside the Union, the general election in Bosnia-Herzegovina saw six new parties gaining parliamentary representation: the centre-right People and Justice party with three seats (5%), the pro-European European Union of Citizens of Bosnia-Herzegovina party with 3% and two seats. Finally, 4 parties obtained one seat each with about 2% of the vote: Justice and Order (Serbian nationalism), Initiative of Bosnia and Herzegovina (Pro-EU), Serbian Unity (Serbian nationalism), and the Democratic Union (Serbian conservatism).

In Northern Ireland, the Green Party, which does not take a position on the institutional future of Northern Ireland, lost its 2 seats and joined the extra-parliamentary opposition. The party had had seats in the Northern Ireland Parliament since 2007. Between 2016 and 2022, the party obtained between 16,000 and 18,000 votes without making any progress.

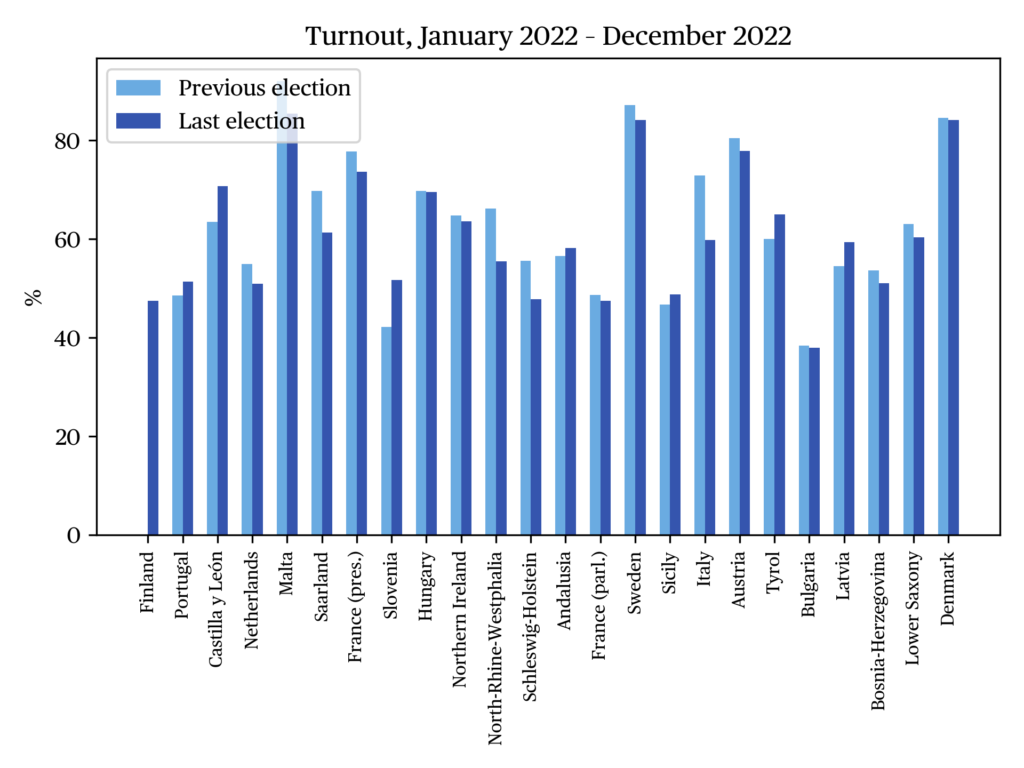

Turnout

In the period covered by this issue, the average voter turnout decreased. This trend affected several crucial elections, despite Europe facing major crises.

In France, two major elections took place between April and June 2022: the presidential election on April 10 and 24, and the legislative election on June 12 and 19.

The two rounds of the presidential election attracted fewer voters than in 2017. There was a -4.1 pp drop for the first round compared to the last election, and a -2.6 pp drop for the second round. As the war in Ukraine began, incumbent President Emmanuel Macron ran a relatively low-key campaign, and there were fewer public debates between candidates. This produced a form of ‘non-campaigning’ which was abundantly discussed in the French media.

As regards the legislative election, no clear trend emerges. Turnout was down -1.2 pp in the first round compared to the 2017 election, but up 3.6 pp in the second round. However, turnout remains very low, below 50%.

In Portugal, an early parliamentary election was held after the Left Bloc (BE) and the Unitary Democratic Coalition (including the Greens and the Portuguese Communist Party) withdrew their non-participatory support for António Costa’s Socialist government. The turnout in this crucial general election increased slightly compared to 2019, exceeding the symbolic threshold of 50%: it gained +2.9 pp from 48.6% to 51.4%.

In Hungary, turnout remained stable at 69% as Victor Orbán succeeded in mobilizing his electorate, in particular by organizing, on the same day, a referendum on issues of sexual education, officially aimed at ending the alleged “promotion of homosexuality and transidentity” in Hungarian schools.

In Malta, despite a well above-average turnout in a European comparison (85.4%), voter mobilization decreased. The March 26, 2022 election saw the lowest turnout since 1955, down 6.6 pp from the 2017 election.

Despite high stakes, turnout in the Italian general elections was much lower than in 2018 (-9 pp). On the same date, early elections were called for the renewal of the Sicilian Regional Assembly. Due to general elections taking place the same day, turnout was higher than in the last election, with a slight increase of +2.1 pp.

In Germany, four regional elections were held in 2022, which all saw severe drops in turnout. In Saarland and Schleswig-Holstein, turnout plunged by more than 8 points (-8.1 pp and -8.8 pp respectively) compared to the previous elections, falling below the 50% mark in the latter. In North Rhine-Westphalia (NRW), turnout fell even more sharply, losing more than 10 percentage points (-10.6 pp). The loss in participation was more moderate in Lower Saxony (-2.8 pp, at 60.31%).

In Austria, the election for President of the Republic, whose executive power is limited, was nevertheless marked by relatively high turnout (65.19%), down by 3.3 pp.

In Bulgaria, turnout, although low in historical comparison, was up by +0.9 pp in October compared to the previous election in November 2021.

The election renewing the Northern Ireland Assembly saw for the first time the Republican and Irish nationalist party Sinn Féin come out on top, in a context where participation remained relatively stable, falling by only -1.2 pp.

In Finland, the first elections for the new regional councils were held on January 23, 2022. Less than half of all voters turned out to vote (47.5%).

In Denmark, two important electoral moments took place in 2022. In the referendum on ending the opt-out from participation in the Common Security and Defence Policy (CSDP) in the European Union, turnout was 65,8%, with a large majority in favor — given the complexity of the matter, such a high turnout is noteworthy. Early general elections were also held on November 1, 2022 for the renewal of the Folketing, the Danish parliament. Turnout remained relatively stable (and high), at 84.2%, down by only 0.4 pp.

Finally, municipal elections were held in the Netherlands. The turnout was historically low, at just over 50%, whereas figures in previous elections were usually around 55%. The large parties dominating the Dutch political scene (VVD, CDA, and the Socialist Party) have seen a considerable decline in their vote shares, with more local parties gaining ground.

In contrast to this overall trend, five elections showed a significant increase in turnout, in Slovenia (parliamentary and presidential), Castilla y León, Latvia, and Tyrol.

In the Slovenian parliamentary elections, turnout rose by 18.3 pp from 52.6% to 71.0%. A presidential election was also held on October 23 (first round) and November 13 (second round). Turnout was up sharply in the first round (+8.2 pp), and in the second round (+11.8 pp).

In the regional elections in Castilla y León, voters turned out in large numbers. Turnout on February 13, 2022, increased by more than 10 points compared to the 2019 election, partly to increased mobilization around the future of the region’s rural areas. In contrast, in Andalusia, turnout went up only slightly (+1.6 pp).

In Latvia, the election campaign saw a confrontation between a camp described as “pro-Western” and another described as “pro-Russian.” A significant increase in participation was observed, with turnout rising to almost 60% (+5.1 pp).

Finally, in Tyrol, a snap election was called following the resignation of the regional governor. The turnout was up by 5 points, and the outgoing coalition lost its absolute majority.

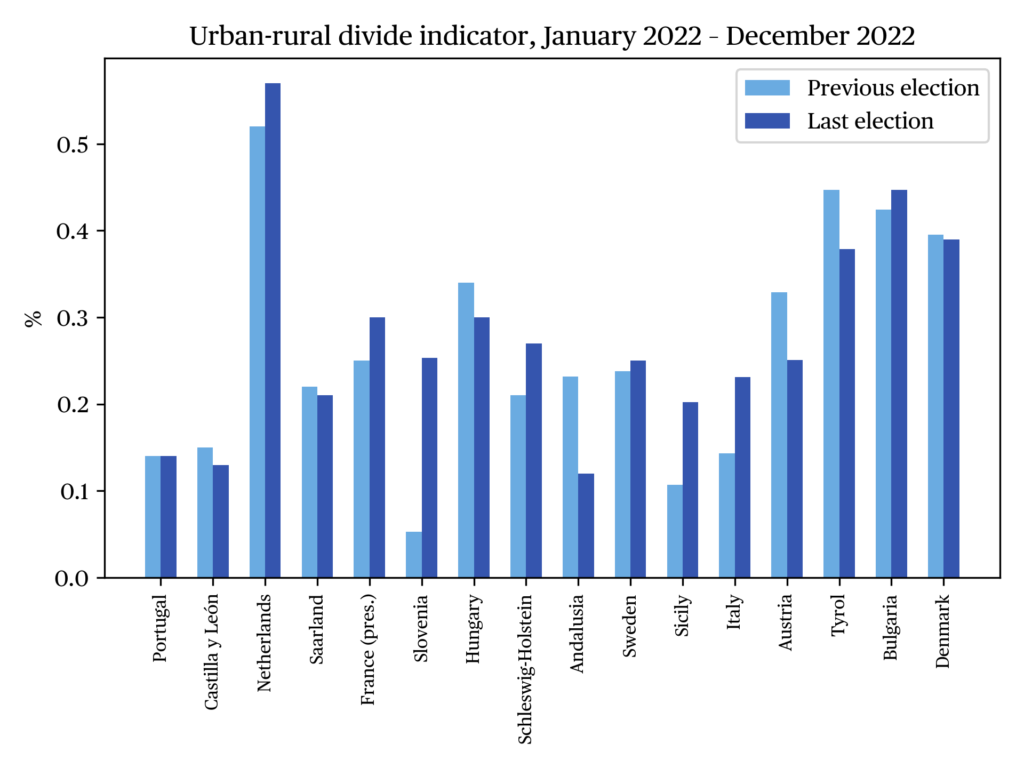

Urban-rural divide

BLUE constructed an indicator to measure the polarization of the vote between urban and rural areas. Given the aggregate vote shares u1, …, up of the parties in the urban electorate and the aggregate vote shares r1, …, rp of these same parties in the rural electorate (in percent), we consider

1/2 ( |r1 – u1| + … + |rp – up| ).

The result is a percentage that varies between 0% and 100%, where 0% means that the shares of the different parties in the urban and rural electorates are identical, and 100% means that the urban electorate votes for entirely different parties than the rural electorate.

For most of the elections covered by this issue, our indicator remained stable. The main exception concerns the Dutch municipal elections, where the indicator is also much higher than in other regions. In fact, 57% of urban voters voted differently from rural voters. In these municipal elections, which showed the lowest turnout since 1955, the rural/urban divide increased even further, by 5 pp.

In the French presidential elections, the gap also widened, increasing by 6 pp from 24% in the previous election of 2017, to 30% in 2022. A clear divide could be observed between the larger metropoles, where support for Jean-Luc Mélenchon was high, the countryside in the North and South of the country which rather voted for Marine Le Pen, and the West of France dominated by the Macron vote. The 2022 election thus saw a deepening of the trends already observed in 2017.

In the Italian general election, the picture is relatively similar. There was an increase of 8 pp, with the indicator rising from 14% to 23%. In the Sicilian regional elections, the indcator also increased from 10% to 20%. The 2022 elections have thus seen a strengthening of the rural-urban divide in Italy.

In Slovenia, the gap only widened slightly by +2 pp, with the indicator raising from 29% to 31%. Overall, the electoral divide between urban and rural voters remained relatively stable. The same holds of the parliamentary elections in Portugal, where the indicator is relatively low (14%), Sweden (25%), Denmark (39%), and Bulgaria (44%, +2 pp). For the Danish opt-out referendum, we do not have a previous point of comparison, but the gap is very small, at 8%.

Hungary, on the other hand, stands out for a decrease in the vote gap between urban and rural voters. In these parliamentary elections, won by incumbent Viktor Orbán, the indicator has dropped by -4 pp, from 34% in 2018, to 30% in April 2022 election.

In Austria, the gap has also shrunk in the presidential election, as the indicator decreased by 8 pp down to 25%. As similar trend can be observed in the Tyrolese regional ballot (-7 pp).

In Germany, the results of two regional elections can be analyzed, in Saarland and Schleswig-Holstein. In Saarland, the indicator fell slightly, losing -1 pp, from 22% to 21%. In Schleswig-Holstein, on the other hand, it increased by 6 pp, to 27%; the divide has thus been reinforced in this state.

After an electoral campaign marked by the issue of rural exodus, Castilla y León showed a decrease in the gap, which was already very low in the last election. The indicator declined by 2 pp compared to the last regional elections, to 13%. The gap shrinks even more strongly in Andalusia, reaching only 12% (-11 p).

Socio-economic determinants of the vote

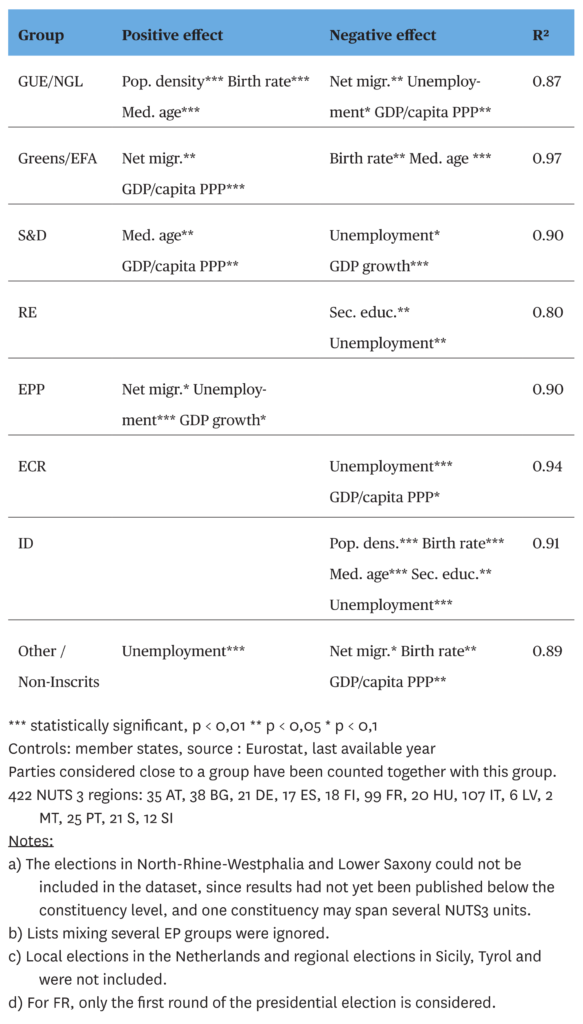

Figure d shows the results of an OLC regression model measuring the effect of seven socio-economic variables observed at the NUTS 2 or NUTS 3 level

2

on the vote for the various European groups.

The vote for the radical-left GUE/NGL group is characterized by a significantly higher prevalence in high-density, high-birth rate, and older regions, and a significantly lower prevalence in areas with high net migration, unemployment, and GDP per capita.

The profile of the Greens/EFA group shows almost entirely inverse effects: a lower age or birth rate positively affects their vote share, as does a high net migration rate or GDP per capita. Overall, the Greens/EFA appear to be overrepresented in affluent, attractive, and younger areas, while the GUE/NGL group performs better in dense areas whose population is older and less affluent, but where unemployment remains comparatively low.

The S&D obtain more votes in older, prosperous regions, while their vote share is negatively affected by both unemployment and economic dynamism (measured by GDP growth). In contrast, the EPP appears to perform better in growing, but high-unemployment regions with a positive net migration rate.

On the other hand, unemployment affects negatively the vote share of the RE and ECR groups, which however seem to perform better in areas with lower educational attainment levels (for RE) and lower GDP per capita (for ECR). This is untypical or urban environments and more typical of environments featuring an intermediate level of economic development.

The far-right ID group is more successful in low-density, low-birth rate, younger, less-educated and lower-unemployment areas. These features can be matched with peripheral, less-attractive areas facing limited economic difficulties, and make for an overall profile diametrically opposed to that of the far-left.

Finally, unaffiliated parties obtain more votes in areas with high unemployment, low net migration rates, low birth rates, and low GDP per capita, which is typical of structurally weaker regions. These parties, which may be either new or located at one end of the political spectrum (most frequently far-right), appear to grow stronger in regions facing the biggest economical and social challenges.

Autonomy — independence

The historic victory of Sinn Féin (far left, Irish nationalist) in Northern Ireland, taking advantage of the partial collapse of the Democratic Unionist Party (radical right, unionist) to become the leading political force in the region, is a major development in Northern Irish politics. For the first time since the formal independence of the Republic of Ireland in 1922, republicans have been able to win in this historically Protestant and unionist region. If Sinn Féin hopes to capitalise on this victory and accelerate the unification of the island, the result of the nationalist party is not a plebiscite and should be put in perspective with the emergence of a third non-partisan party, positioned in the centre of the political spectrum. By obtaining 17 seats, 9 more than in the 2017 elections, the Alliance wants to be a pivotal force in Northern Irish politics, especially as the issue of the Northern Ireland Protocol, allowing the free movement of goods and people between the North and the South of the island of Ireland, is at the heart of political tensions in the region. While the Unionists would like to denounce the agreement, the Nationalists and the Alliance are keen to preserve it for reasons of identity, culture and trade.

In the French National Assembly, the Corsican autonomists of Femu a Corsica and Partitu di a nazione corsa keep the 3 seats out of 4 obtained in June 2017. The 1st constituency of Corse-du-Sud remains in the hands of the insular right, allied to the party of former Prime Minister Edouard Philippe. The 3 autonomist deputies will undoubtedly be part of the negotiations on the institutional future of Corsica initiated following the unprecedented riots in Corsica in March 2022, following the death in prison of pro-independence militant Yvan Colonna, murdered by a fellow prisoner. Brittany officially elects Paul Molac, who ran under the regionalist banner, formerly a Socialist MP and then LREM. He left the LREM group during the 2017-2022 legislature to form the “Liberté et Territoires” group with centrists and Corsican autonomists. In the overseas territories, the Tahitian and Martinique independence parties and the Reunionese regionalists also obtained seats and strengthened the NUPES coalition (left to far left) in the National Assembly.

In Sicily, the Movement for Autonomy, a member of the centre-right coalition of President Renato Schifani, maintains its presence in the regional parliament with three seats, while regionalist Sud chiama Nord (SCN) newly holds eight seats. In the Italian general elections, the various autonomist currents (in the Aosta Valley, South Tyrol, and Southern Italy) maintained their overall influence in the two houses of parliament: the Union valdôtaine (Greens/EFA) holds one seat in the Chamber, the South Tyrolese People’s party (SVP, EPP) holds three seats in the Chamber and two in the Senate, and SCN controls one seat in each house.

Anti-corruption movements

While corruption issues were discussed in the campaign preceding some of the elections, most notably Hungary, Slovenia, Malta, and Bulgaria, it seems that only in Slovenia these accusations translated into concrete political change.

There are obvious corruption issues in Hungary, additionally to breaches in the rule of law and biases in the campaign funding. Yet the anti-Orbán coalition did not manage to become a credible anti-corruption movement and they eventually lost the election — as Eszter Farkas explains, this can be explained, among others, by the different parties themselves not being free of corruption scandals.

In Slovenia, whose political scene has been characterized by relative political instability since 2008, several corruption scandals emerged during the COVID-19 pandemic, as well as allegations of meddling with independent state institutions. This led to anti-government protests centered on anti-corruption demands, which especially targeted the incumbent populist Prime minister Janez Janša (SDS, EPP) and his inner circle. Janša’s government distributed energy vouchers to the general population just two weeks before the election. Relative newcomer Robert Golob (Svoboda, RE), who encouraged anti-government feelings, was eventually elected Prime minister. In the run-up to the election, Golob himself was accused by opponents of having undeclared foreign bank accounts; these allegations, however, seems to have had little impact on his election. A similar scenario unfolded in the presidential election leading to the election of independent president Nataša Pirc Musar.

Malta was shaken by large scale corruption scandals in the past few years. The “Golden Passport Scheme” as well as the murder of journalist Daphne Caruana Galizia and the revelations of the Panama and Pandora papers influenced national politics in the last few years and impacted this year’s election. Similarly to Slovenia, the Maltese government distributed “supplementary cheques” and offered tax rebates in the weeks prior to the election. Despite consistent negative press on the island, the anti-corruption movement did not manage to capitalize on the dissatisfaction; on the contrary, it seems that citizen’s anger rather resulted in abstention, with participation dropping by 7 pp (from 92% to 85%).

In Bulgaria, where accusation of corruption against long-serving Prime minister Boyko Borisov (2009-2022) triggered massive protests in 2020-2021, citizens were called to vote for the fourth time in eighteen months. In the aftermath of the protests, several new political movements emerged, among which TV moderator Slavi Trifonov’s There is such a people (ITN, populist) and liberal-centrist Continue the change (PP) led by Harvard graduates Kiril Petkov and Asen Vasilev. The far-right pro-Russian party Revival (NI) also gained ground in the course of 2022. Following a first ballot in April 2021, the incapacity of the various political parties to negociate a stable government coalition has led to snap elections being held in July and November 2021, as well as in October 2022. The new anti-corruption and former opposition parties mostly reject government collaboration with Borisov’s GERB (EPP) party, but are also internally divided between ‘Russophiles’ and ‘Russophobes,’ as well as by diverging policy preferences. The holding of a fourth snap election in 2023 cannot be excluded.

Oversea territories

Four elections discussed in this issue have taken place in part in Outermost Regions (OMR) and Oversea Countries and Territories (OCT) of the EU: The French presidential and legislative election has been held in all French oversea territories, the Portuguese general election in the Portuguese OMRs of Azores and Madeira, and the Danish general election in the Danish OCT of Greenland.

The result of the vote of French oversea residents diverged strongly from the national average. In the first round of the presidential election, third-placed Jean-Luc Mélenchon (FI, GUE/NGL) won a majority of the vote in three OMRs (Guadeloupe, Martinique, Guyane) and a plurality in two others (Saint-Martin and Réunion), while in Mayotte — the EU’s least developed first-level region —, Marine Le Pen (RN, ID) obtained 43% in the first round. Unlike a majority of left-wing voters in mainland France, and largely due to dissatisfaction with the incumbent’s performance after years of unresolved social and political tensions, oversea voters more often supported Le Pen against Macron in the second round, giving her a majority in all OMRs. In two other OCTs located in the Atlantic Ocean (Saint-Pierre-et-Miquelon and Saint-Barthélémy), similar trends were observed, while in the Pacific OCTs of French Polynesia, New Caledonia, and Wallis and Futuna, Emmanuel Macron came out on top in both rounds. Turnout was lower than average in all oversea territories, with the very low figures registered in New Caledonia (35%) largely reflecting pro-independence parties’ refusal to participate in the voting process. Overall, the vote of oversea residents highlighted the growing disconnect between metropolitan French dynamics and the public opinion of oversea territories, as well as the dissatisfaction of the latter vis-à-vis central authorities.

In comparison, the electoral behavior in the autonomous regions of Azores and Madeira, whose level of political autonomy is larger than that of their French OMR counterparts, was less distinctive. In the two regions, the PSD (EPP), unlike in other constituencies in the country, ran on a common list with other right-wing parties. The PSD-led coalition won in the Madeira constituency (its only victory in a Portuguese constituency), obtaining its third best result nationwide, while the PS won in the Azores constituency. Both the far-left BE and the far-right Chega underperformed in the two regions.

Much like in the case of Portugal, the results of the Danish snap elections in Greenland demonstrate the relative autonomy of the country has from mainland Danish politics. As part of the Danish Kingdom, Greenland has 2 seats in the 179-strong Folketing. Both seats have been controlled by the same two parties since 2001. These parties are both pro-independence and have a left-wing program. As Greenland is not a part of the EU since it left the EEC in 1985, none of them has a European affiliation, although Siumut (“Forward”), the dominant party since Greenland’s autonomy in 1979, seats with the Social-Democrats (S&D). In line with their 2021 drop in the Greenlandic parliamentary election, the left-wing nationalists from Inuit Ataqatigiit (“Community of the People”) lost votes, finishing second with 24,6% (-8,8 pp). This loss benefited Siumut (37,6%, +8,2 pp), who won the election for the first time in 15 years. The Democrats, the centre-right unionist party affiliated to the Danish Social Liberals (RE), reaffirmed their status as the main unionist party and had their best scores in 17 years, with 18,5% (+7,6pp). As it already was 3 years earlier, voter turnout continued to plummet below 50%, with 47,78% of registered voters participating.

European issues

These elections were also impacted by EU news and developments, and in some cases, their outcome is likely to have consequences for EU decision-making, especially in the European Council.

Firstly, the invasion of Ukraine on 24 February 2022 largely captured media interest, turning the coverage of national and regional elections into a secondary priority. In the Netherlands, Malta or Castilla y León, the elections were less covered by the national press. It is also likely that the onset of the war disserved pro-Russian parties and those with close ties to the Putin regime — except in the case of Hungary, where Fidesz won a parliamentary majority. The impacts of the war — in particular the European sanctions on Russia, its consequences on supply chains, and the energy situation — were also at the heart of electoral debates within member states. In Hungary, the victory of Viktor Orban’s Fidesz party, which since the beginning of the war has pursued a policy of strategic ambiguity towards the Putin regime, threatened European unity. Indeed, while Hungary accepted the first five packages of European sanctions against Moscow, it blocked the adoption of the sixth package, which included an embargo on Russian oil. Hungary finally obtained a temporary exemption for oil imports by pipeline, allowing it to continue buying cheap oil from Russia. Since then, Orbán has met with Russian Foreign Minister Lavrov in Moscow to discuss the purchase of 700 million cubic meters of gas.

The resurgence of war on European territory has led Denmark to renounce its opt-out clause concerning the European Union’s Common Security and Defence Policy (CSDP). On June 1, 2022, the referendum on CSDP integration won broad support with 66.87% of the vote. Traditionally Atlanticists, the Danes are now fully participating in the EU’s foreign policy.

In the second half of 2022, the war and the resulting energy crisis further monopolized the electoral debates in several states and regions, again relegating national or regional issues to the background. In Bulgaria, the elections were held early due to the fall of the Petkov government, due in part to differences of opinion over support for Ukraine. While the government — especially the PP (~RE) and DB (EPP) parties — wanted to support Ukrainian citizens in a more assertive way, the president, Radev, was in favour of more moderate aid. Similarly, while the government was heavily criticized for diversifying its energy supply sources, driving up the price of electricity, the caretaker government put in place by Radev after the call for early elections tried to reverse the coalition’s positions by starting talks with Gazprom to restore gas supplies to Bulgaria.

Beyond the Russian-Ukrainian war, other political trends are also of European relevance. In the following, we underline a) the new nationalist majority in Northern Ireland b) the election of a pro-European presidency in Bosnia and Herzegovina and c) the continued rise of neonationalist and eurosceptic parties throughout Europe.

In Northern Ireland, the Irish nationalist Sinn Féin became for the first time the leading party in the Northern Ireland assembly with 27 seats, relegating the Democratic Unionist Party (DUP) to the second place with 25 seats. After DUP First Minister Paul Givan resigned in February to protest against the implementation of the Northern Ireland Protocol as part of the Brexit process, his party still refuses to form a new government unless border controls are abandoned. Although British MPs unilaterally voted to revise the protocol in June, this decision is subject to an infringement procedure by the European Commission, leaving the conflict unresolved. The appointment of a new First Minister in Northern Ireland remains suspended to the renegotiation of the protocol. As of December 2022, the position of First Minister is still vacant.

This issue also features a special analysis dedicated to the presidential and parliamentary elections in Bosnia and Herzegovina, which has been a candidate for entry into the Union since 2016, and whose official candidate status was approved by the European Affairs Ministers on December 13, 2022. The election of the collegiate presidency on October 2, 2022 saw the victory of the Bosnian Denis Becirovic, the Croatian Željko Komšić and the Serbian Željka Cvijanović, all three pro-Europeans.

Several eurosceptic, neonationalist, and populist parties gained (additional) parliamentary or government representation in 2022. In Hungary, Fidesz strengthened its position while the far-right parties in Spain and Portugal saw their vote share increase. The second half-year also saw the rise of the far right in Italy and Sweden. In Italy, the parliamentary elections of September 25 were won by the centre-right coalition with 43.82% of the vote. FdI (ECR) obtained 119 seats — 87 more than in 2018 — making its leader Georgia Meloni the new head of government. While she once claimed to be a eurosceptic, Meloni has since then moderated her positions in order to broaden her electoral base. Her FdI party, however, still advocates a restrictive immigration policy and a ‘return’ to conservative values regarding LGBT and reproductive rights. Similarly, for the renewal of the Riksdag in Sweden, while the Social Democratic Party came out on top with 30.33% of the vote, the nationalist and populist Sweden Democrats managed to come in second, obtaining 20.54% of the vote, 3 points more than in 2018. The party is openly eurosceptic, Islamophobic and anti-immigration.

On the other hand, Volt, a pan-European political party, was represented in the Dutch municipal elections and the Maltese parliamentary elections. In the Netherlands, it was only present in a few municipalities, while in Malta, its result appeared disappointing, partly due to its pro-abortion position which is not consensual on the island. The party currently polls over 10% in the Netherlands, and officially supports the PP coalition in Bulgaria.

Finally, the European news is also marked by the biggest corruption scandal in the history of the European Parliament. Eva Kaili, Vice President of the institution, is defeated from her duties after being indicted for corruption. She is suspected of having received large sums of money from Doha to “influence the political and economic decisions” of the Parliament.

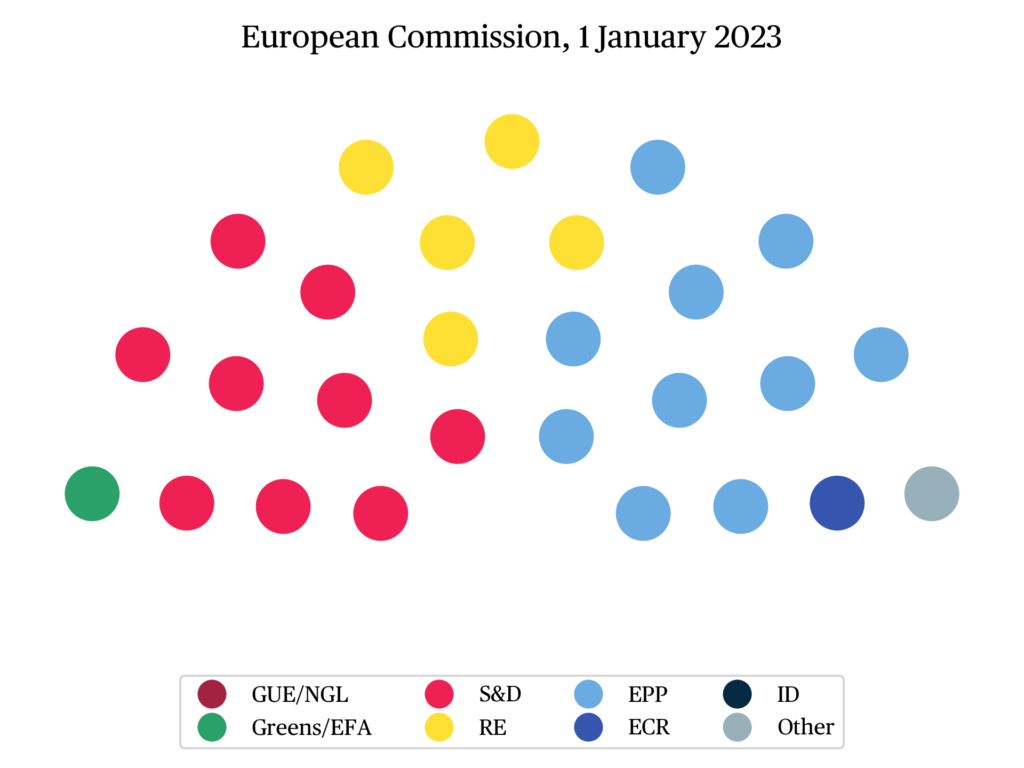

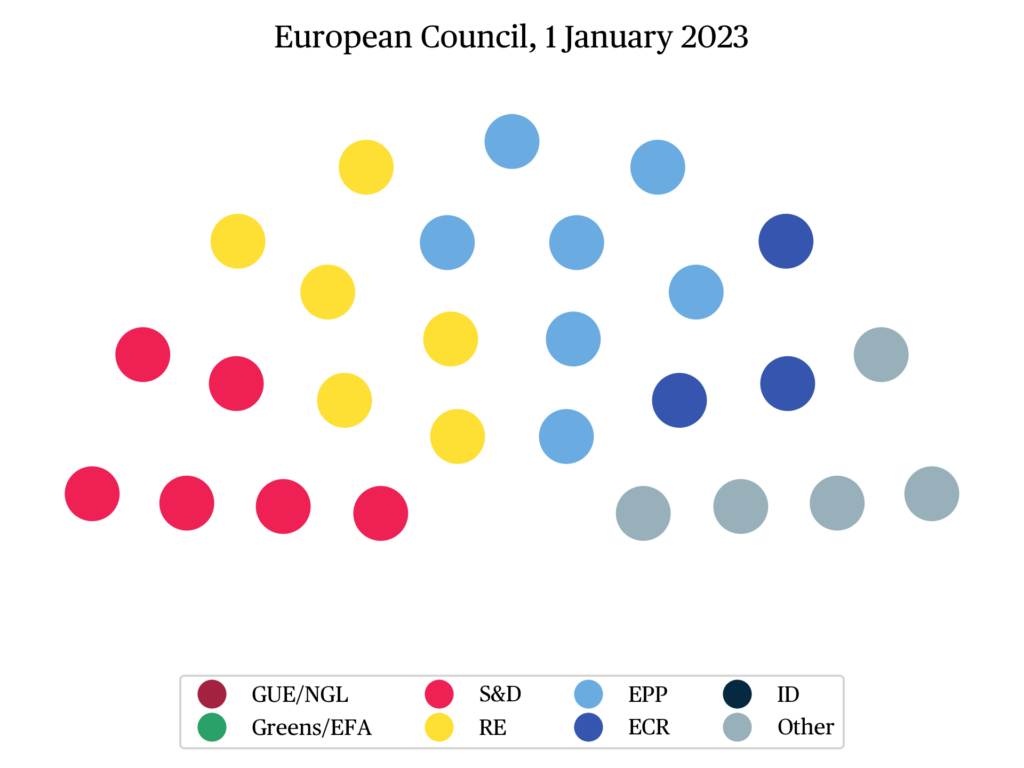

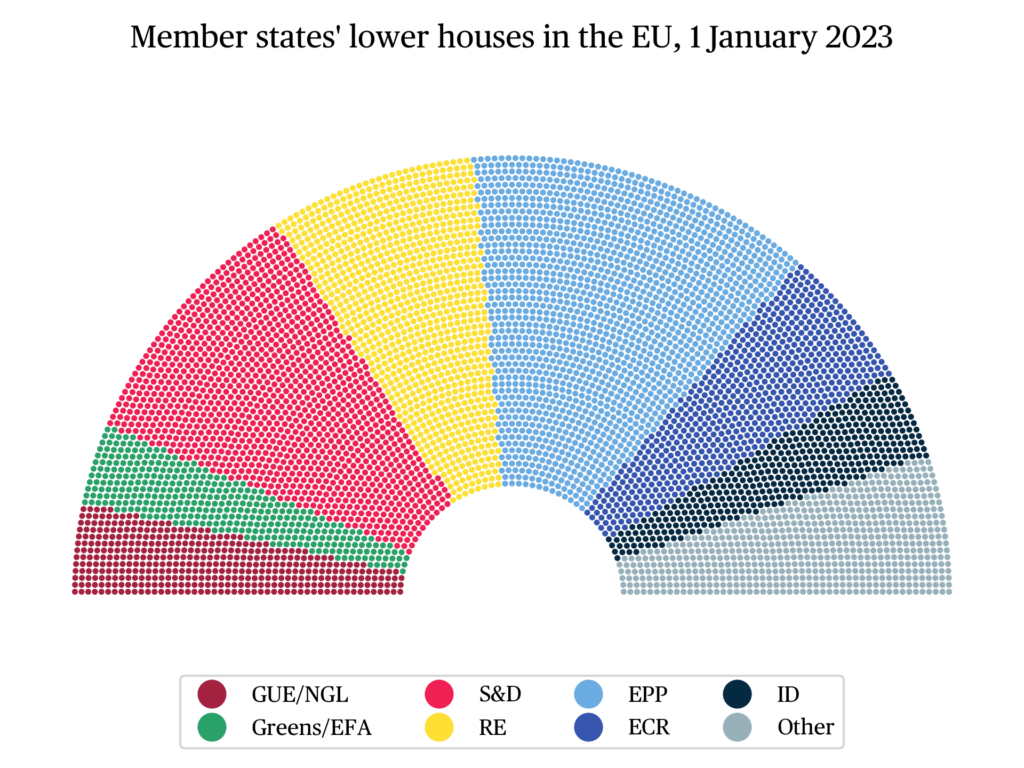

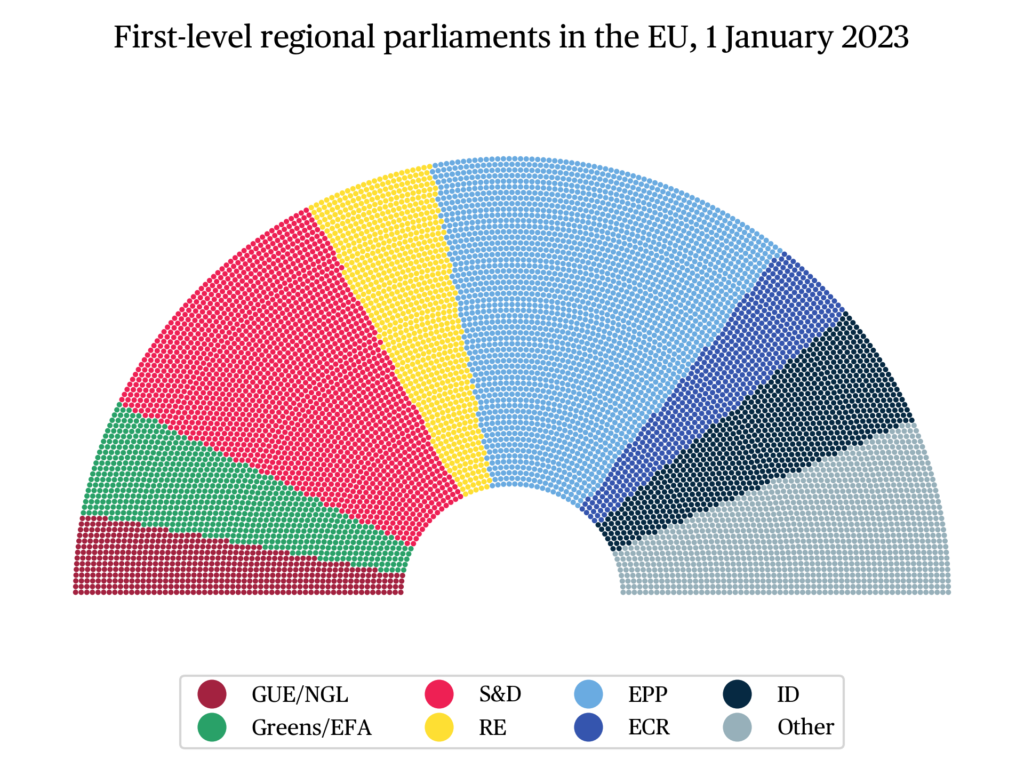

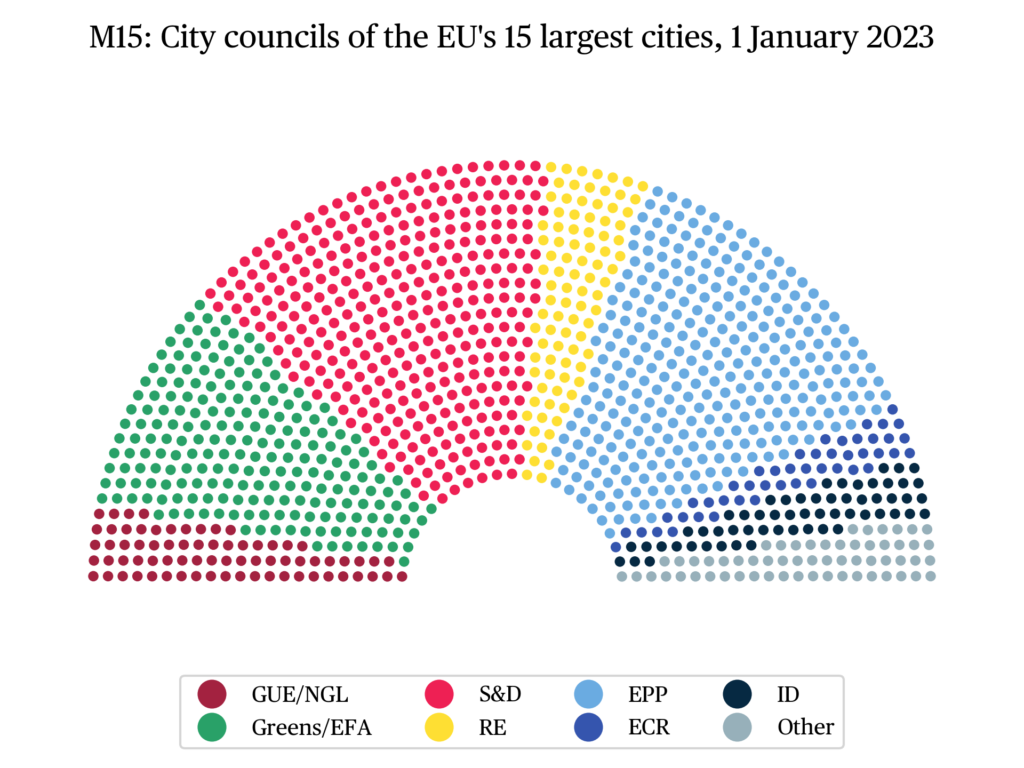

Seat shares of European political families, 1 January 2023

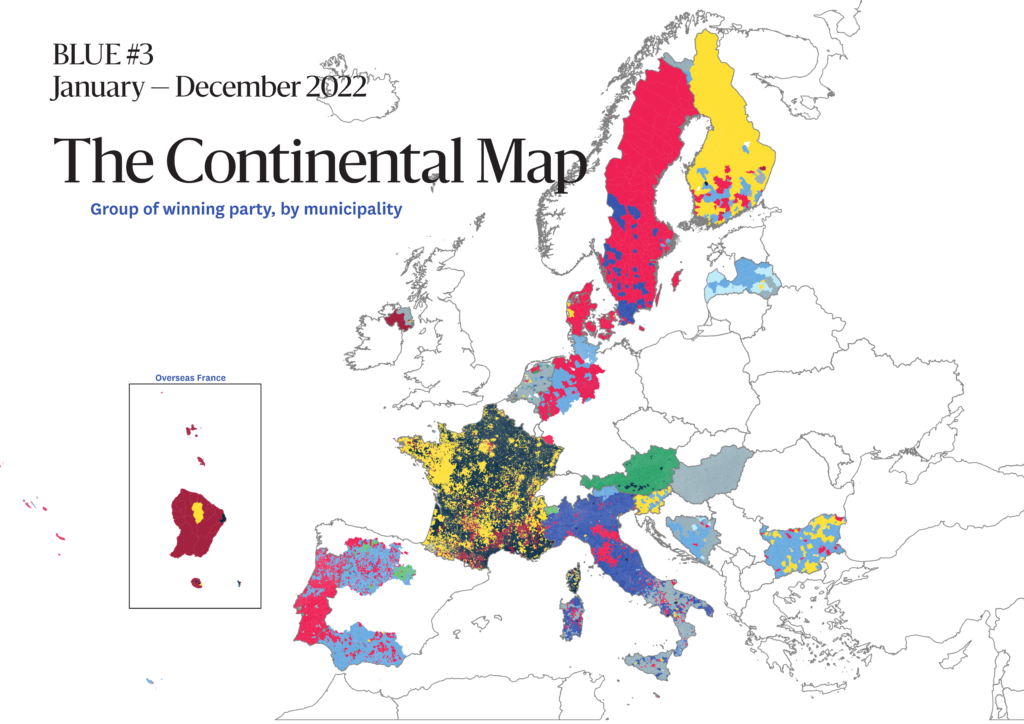

The Continental Map

Notes

- In order to facilitate inter-semester comparison, the average values presented below exclude elections in Northern Ireland and local elections in the Netherlands, which are dealt with in a special section of this issue, to include only national and regional elections.

- Namely: population density, birth rate, median age, net migration rate, unemployment rate, GDP per capita (PPP), growth of GDP per capita (PPP), share of individuals with secondary education.

citer l'article

François Hublet, Jean-Toussaint Battestini, Lucie Coatleven, Jean Cotte, Charlotte Kleine, Mattéo Lanoë, The Continental Review, Oct 2022,

à lire dans cette issue

voir toute la revue