10 Key Lessons of the 2024 European Parliament Election

François Hublet

Editor-in-chief, BLUEIssue

Issue #5Auteurs

François Hublet

Issue 5, January 2025

Elections in Europe: 2024

BLUE is releasing BLUE_EP, the first dataset of Europe-wide, local-level results of the 2024 and 2019 European Parliament elections. This dataset covers approximately 100,000 local administrative units and over 500 parties for the 2024 election alone. In this article, we provide an overview of the main insights offered by this unique dataset, focusing on key European-level developments.

Throughout this article, results are reported for the seven European Parliament groups, with non-affiliated and “Non-Inscrits” parties classified into four categories based on their ideological profile: Other (left), including left-wing nationalists; Other (center-right), including center-right regionalists/nationalists; Other (radical right); and Other, for parties without any clear position on the left-right axis. This classification is an integral part of the BLUE_EP dataset. Coalitions of well-identified members of distinct political groups are reported separately. We further combine the seven groups, the four non-affiliated categories, and the cross-group coalitions into four broader “political families”: Left (including The Left, Greens/EFA, and S&D); Center-right (including Renew Europe and the EPP); Radical right (including the ECR, ID/PfE, and ESN); and Other (for other non-classified parties and alliances spanning beyond political families).

Minor discrepancies may exist between the results reported below and those reported by member states’ election authorities, as the BLUE_EP dataset relies solely on local data and uses a standardized method to compute vote shares that may differ from national calculations.

BLUE_EP is open data. To obtain additional information about and access the BLUE_EP dataset, our academic readers can check the corresponding Zenodo entry.

1. A Rightward Shift and the Erosion of Green and Liberal Aspirations

The 2024 EP election saw the Parliament shift to the right in both votes and seats, a development that could be expected early on. This rightward shift was mostly driven by Green and Liberal losses, with the two groups’ vote shares contracting by 32% (3.21 pp) and 26% (3.17 pp), respectively, alongside a simultaneous increase in far-right votes (+25%).

The Left group GUE/NGL and the right-wing ECR were the only groups to increase their vote share, while the far-right Patriots for Europe (PfE, formerly ID) nominally lost votes against the backdrop of the formation of a smaller AfD-led group, Europe of Sovereign Nations (ESN). Meanwhile, the vote shares of traditional center-left (S&D) and center-right (EPP) groups remained relatively stable. The 2024 election also saw broad alliances spanning across the political center taking first place in both Poland and Romania.

As a result, the share of left-wing votes decreased from 43.08% to 36.86% (-6.22 pp), while the share of center-right votes contracted slightly from 33.41% to 31.11%. In contrast, the share of radical-right votes increased from 21.84% to 27.25% (+5.42 pp). While, following the 2019 election, the median voter in the EU27 was a Renew Europe voter, it is now a center-right EPP voter—a shift with potentially momentous institutional consequences (see point 3 below).

The overall trend of a weakening left and a strengthening radical right was relatively homogeneous across member states. Only in Finland, Italy, and Poland—three countries currently or recently governed by at least one radical-right party—did the radical right lose electoral ground, while the left only made significant gains in Finland and Sweden. The situation on the center-right was more contrasted, with a few major successes (Slovakia, Slovenia, Germany, Malta) as well as clear electoral defeats (Lithuania, Spain, Austria).

2. Steady Voter Turnout with Notable National Differences

The overall turnout at the European level appears stable, at 50.74% versus 50.66% in 2019 (+0.08 pp). However, this figure masks important national differences in both levels and trends.

Turnout was highest in Belgium with 89%, followed by Luxembourg with 82% and Malta with 73%. At the other end of the spectrum, only 21% of Croatian registered voters and 29% of Czech and Latvian voters went to the polls.

Significant increases in turnout were observed in Hungary (+15 pp), Cyprus (+14 pp), Slovenia (+13 pp), and Slovakia (+11 pp). The number of countries with less than a third of voters turning out decreased from 5 to just 2 (Lithuania and Croatia). At the same time, several member states with relatively high turnout in 2019 saw a marked downward trend, such as Lithuania (-24 pp), Greece (-18 pp), and Spain (-15 pp). In all three cases, the 2019 election had been held simultaneously with local or national elections, while the 2024 election was not. The Belgian, Hungarian, and Romanian ballots coincided with other elections in 2024.

3. The New Coalition Landscape: the EPP as King and Kingmaker

The rightward shift in vote shares is reflected in the composition of the new European Parliament. The median MEP is now a member of the European People’s Party group, whereas it was previously a member of the Renew Europe group. The EPP not only remained the largest group by far with 188 seats, gaining ground (+11 with respect to 2023), but also became the central group in the new European assembly. The Greens (53 seats, -19) and Liberals (77 seats, -24) went from being the third and fourth largest groups respectively to taking fifth and sixth place behind the radical-right PfE (84 seats, +18) and ECR (78 seats, +12) groups, a symbolic blow for centrist forces. Meanwhile, the Left made limited gains, at 46 seats (+9), and the newly formed ultranationalist ESN holds 25 seats.

As had been anticipated before the vote, the EPP can now leverage two different parliamentary majorities: the traditional centrist coalition with the S&D and RE, optionally also extending to the Greens/EFA group, that supported Ursula von der Leyen’s new bid for Commission president; and a new, informal coalition with far-right forces that was activated in October when the EP passed several ESN-backed budget amendments. Meanwhile, the left-liberal coalition between GUE/NGL, Greens/EFA, S&D, and RE is no longer close to holding a majority of seats, reducing their previous influence on key matters such as environmental law and stripping the Liberals of their role as kingmakers in the EP.

4. The Centrist Coalition’s Shrinking Majority

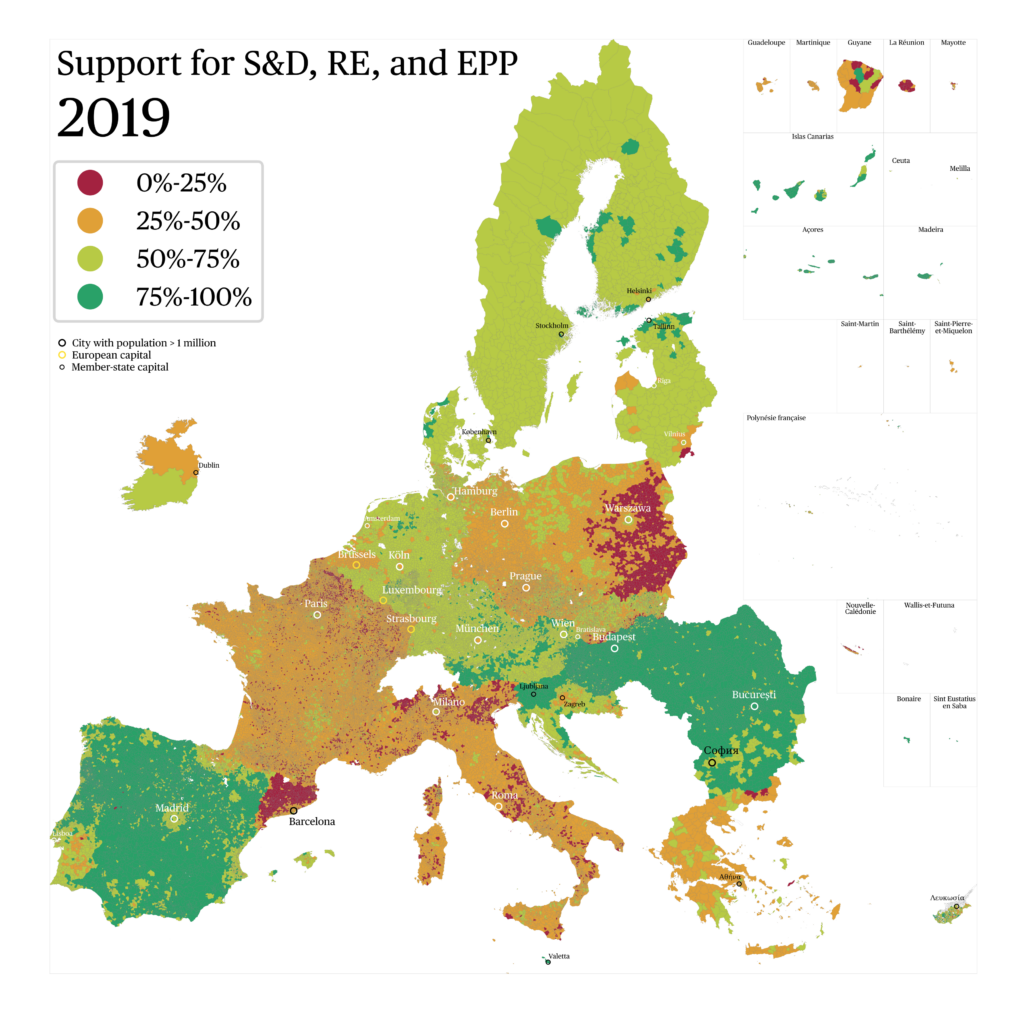

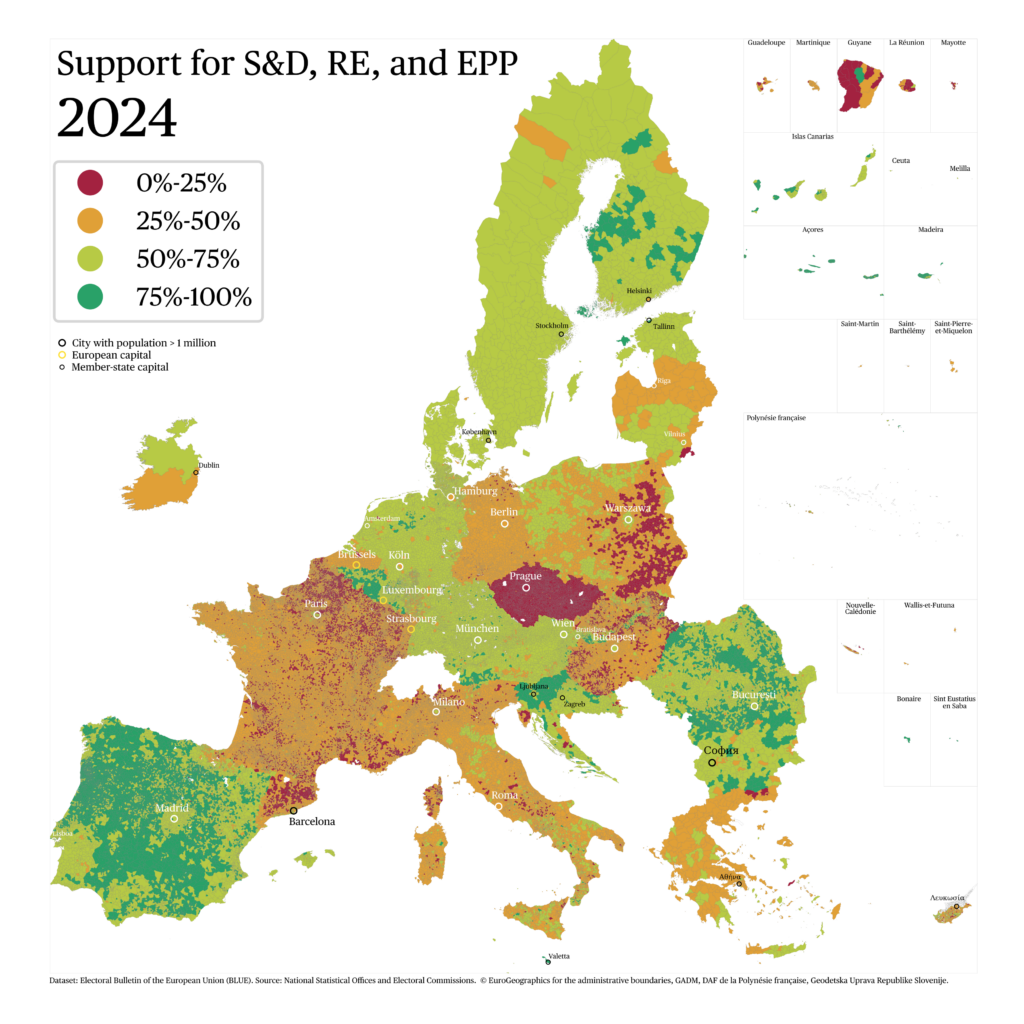

Support for the centrist coalition of S&D, RE, and EPP has decreased since 2019. The parties of the coalition remain strong in the Iberian Peninsula (except Catalonia and the Basque Country), the Nordics, the Benelux (except Flanders), German-speaking regions (except Eastern Germany), Slovenia, and Croatia. However, even in these historical strongholds, its total vote share has regressed, sometimes dramatically.

With Orbán’s Fidesz leaving the EPP for the PfE group, Fico’s Smer’s suspension from the S&D group, and Babiš’s ANO switching from RE to PfE, the former nominal centrist strongholds in Hungary, Slovakia, and the Czech Republic have disappeared. The center has also lost its majority in Latvia, where right-wing parties are on the rise. Some areas with low centrist presence show a slight increase in the coalition’s vote shares (Catalonia, Eastern Poland, Italy) while in France and Eastern Germany, the remaining pockets of support have further weakened.

On average, regions with a low level of support for the three centrist groups tend to be characterized by a less positive opinion of the European Union among their electorate. In the 2024 EU post-electoral survey, the lowest rates of overall positive opinions were measured in the Czech Republic, France, and Greece. The share of positive opinions in Belgium, Poland, Latvia, and Slovakia was equal to or slightly below the EU average. At the same time, some member states display both high rates of Euroscepticism and a comparatively high level of support for centrist parties, as is the case in Slovenia or Austria.

5. The Far-Right’s New Geographic Dominance

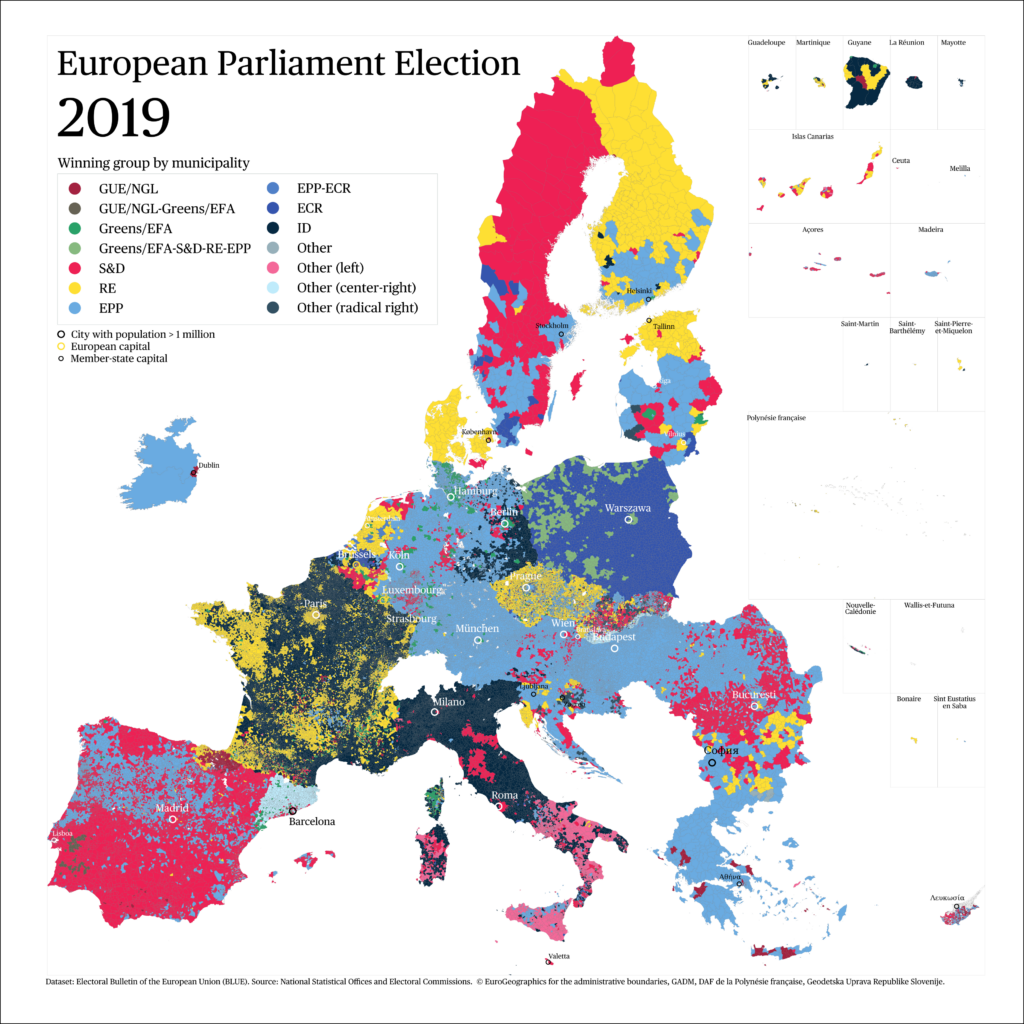

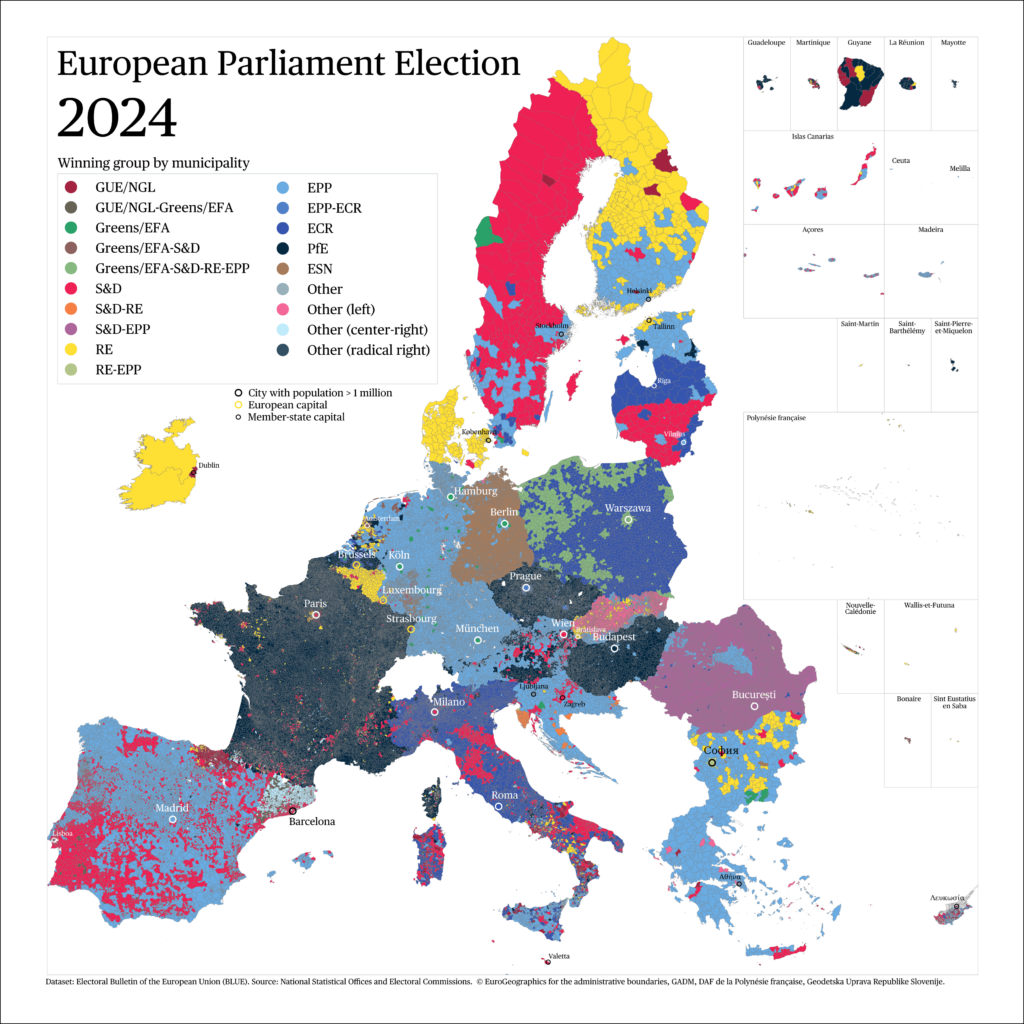

The growth of the far-right is particularly evident when comparing the maps of municipality-level winners in the 2019 and 2024 elections.

In both elections, the French RN, the Hungarian Fidesz, and the Czech ANO (all now PfE) have won the vast majority of their respective member states’ municipalities. Radical right-wing parties have also won in most Flemish, Polish, and Italian municipalities, with Meloni’s FdI replacing Salvini’s Lega as the dominant right-wing player in Italy. In 2024, the French RN, the German AfD, and the Austrian FPÖ have all further improved their geographic reach, with an overwhelming majority of French, Eastern German, and South-Eastern Austrian municipalities now placing PfE candidates in the lead.

As a result, across all local administrative units in our dataset, 47.61% (or 42,363 administrative units) are won by the PfE, 21.10% (or 18,772) by the EPP, 8.58% (or 7,637) by the ECR, against just 7.37%, 2.22%, and 0.15% for the S&D, RE, and Greens/EFA respectively. In 2019, the share of municipalities won by the ID group was 33.17%, followed by the EPP with 26.54%, RE with 17.52%, and the S&D with 11.61%. In 2024, for the first time, more than half of the EU’s municipalities have been won by radical-right candidates.

However, the radical right’s results are significantly inflated according to this metric by the large number of very small municipalities in France (a PfE stronghold) and the dominance of the ECR, PfE, and ESN groups in many sparsely populated, rural areas.

6. People Vote, not the Land: Why There is No Far-Right Hegemony

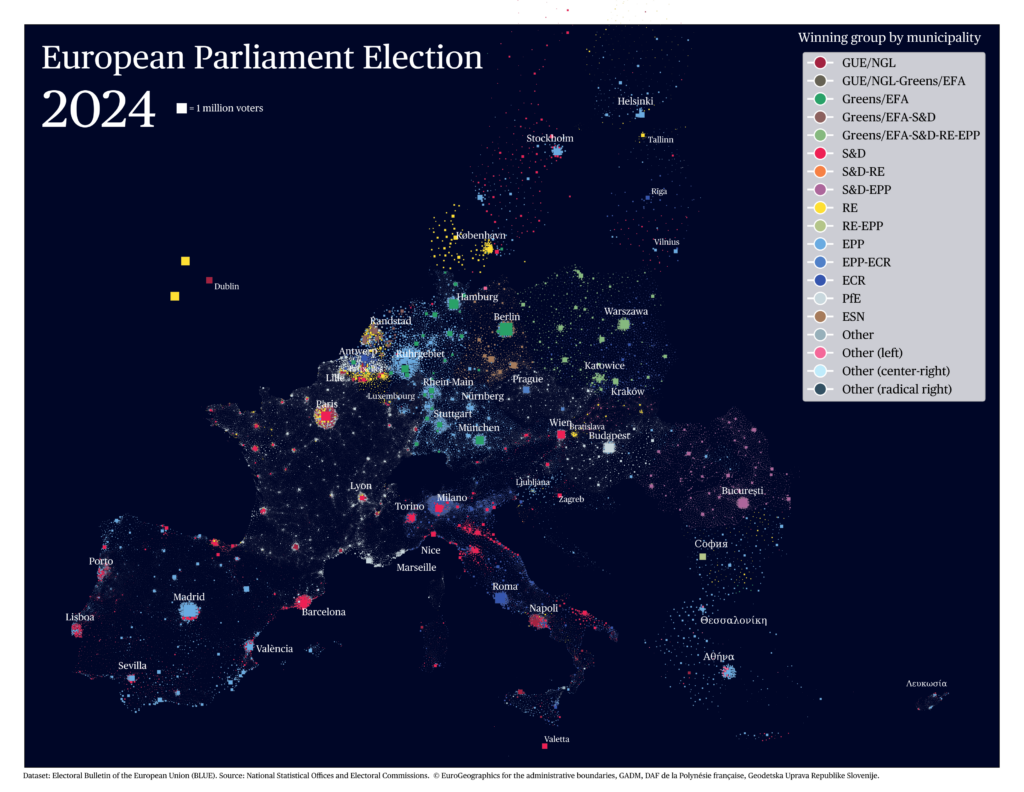

The map below shows a different view of the distribution of municipality-level winners, with every municipality represented as a square proportional to the number of voters in the 2024 EP election. All metropolitan areas with a population larger than 1 million inhabitants are marked.

When taking into account absolute voter counts, the far-right dominance can be qualified and (partly) relativized. While by far the strongest force in rural areas and towns of France, Eastern Germany, Hungary, Italy, Poland, Czechia, Flanders, etc., radical right-wing parties have won few major metropolitan areas: only Budapest, Marseille, and Nice have been won by the PfE group, while the ECR won Rome, Prague, and Antwerp. Among the 15 European municipalities with over 1 million inhabitants, 4 have been won by the Greens/EFA (Berlin, Hamburg, Munich, Cologne), 4 by the S&D (Paris, Milan, Barcelona, Vienna), 2 by the EPP (Madrid, Athens), 2 by other centrist coalitions (Bucharest, Sofia), 2 by the ECR (Prague, Rome), and only 1 by the PfE (Budapest). The 47.6% of municipalities won by the PfE at European level are only home to 17.17% of voters.

When weighting the municipalities by their population, the EPP takes first place with 30.92% (+3.37 pp with respect to 2019), followed by the PfE (17.17%, +0.34), the S&D (12.44%, -6.85 pp), the ECR (12.14%, +6.89 pp), RE (5.79%, -8.59 pp), and the Greens (3.97%, -3.06 pp). These results reflect the Greens’ and Liberals’ severe losses and the right’s success, but do not support the claim of a “far-right hegemony” suggested by a simplistic analysis of the land map.

7. The Local Level: A Continent of Many Political Nuances

Despite contrasting results, all political groups in the European Parliament have obtained high vote shares in their historical strongholds. The table below shows the largest vote shares obtained in local administrative units with over 1,000 inhabitants by each of the groups. The largest vote shares are generally secured by parties representing linguistic or ethnic minorities (AR, DPS, SFP, UDMR, LLRA-KŠS…).

8. The Growing Divide Between Urban and Rural Communities

For the first time, the BLUE_EP dataset provides direct insights into the behavior of different sizes of municipalities at the European level.

The graph below shows the difference in voting behavior in urban and rural areas in the 22 member states for which complete data is available at the level of Eurostat’s Local Administrative Units (LAUs). In 18 member states, left-wing and center-left parties obtain more votes in urban than rural areas, with margins as high as 13 points (Germany) or 12 points (Finland). Similarly, in 18 member states, radical-right parties secure more votes in rural areas, with the difference reaching 12 points in Hungary and 10 points in France. However, there is no homogeneous trend for center-right parties and non-voting.

Overall, the gap in voting patterns between urban and rural areas has widened between the 2019 and 2024 elections in 15 of 22 member states (all except Bulgaria, Spain, Croatia, Italy, Lithuania, Luxembourg, and Poland). In particular, the gap in radical-right vote has increased in 18 member states, paralleling the rise in radical-right vote in mostly rural communities. The available empirical data supports the claim of a rising gap in far-right vote between urban and rural voters over the course of the last legislative term.

9. The Realignment of Europe’s Nationalist Parties

Following the June 2024 election, the landscape of European nationalist parties has undergone significant reorganization.

The RN-dominated Identity and Democracy Group (ID) was rebranded as Patriots for Europe (PfE) and welcomed Orbán’s Fidesz (formerly EPP, then NI) and Babiš’s ANO (formerly RE) within its ranks. The two populist leaders thereby realigned themselves with their closest nationalist allies after years spent in opposition to the mainstream pro-European course of their former European groups. PfE was also joined by Vox’s 6 MEPs (ex-ECR), previously considered close Meloni allies.

The ID/PfE group lost the Finnish PS to the right-wing conservative, Atlanticist ECR group in 2023. The ECR also welcomed the Latvian LVŽS’s single MEP (formerly Greens/EFA) and grew in size thanks to the good performance of many of its member parties, especially Meloni’s FdI, now the largest political force.

The AfD, expelled from the ID group following a series of scandals, created its own Europe of Sovereign Nations (ESN) group together with a few other ultranationalist forces. The group is the current parliament’s smallest, with only the AfD, Polish Konfederacja and Bulgarian Văzrazhdane holding more than 3 seats.

A limited number of other nationalist parties did not join any group, among which are the left-wing nationalist Smer-SD (Slovakia) and Se Acabó La Fiesta (Spain).

10. A Shift in Parliamentary Power Among Member States’ Delegations

The election of EP leadership and Committee leadership revealed a modified balance of power between member-state delegations. These offices are primarily distributed among the European political groups, with no obligation to respect national quotas.In 2024, as in 2019, the PfE and ESN groups have been excluded from the distribution of elected offices, while the ECR has not, in application of the “cordon sanitaire” policy.

Italy, Poland, Romania, Spain, and Sweden, five countries with strong centrist parties and (except for Spain) also a strong ECR component, have secured the largest gains in elected offices in the new European Parliament. Countries with a high share of non-centrist vote such as France, the Czech Republic, and Greece obtained fewer offices than their share of the overall population. France, which has a high proportion of radical-right and radical-left voters, ranks only sixth in number of elected MEPs, behind Germany, Italy, Spain, Poland, and Romania, gaining only one elected member—a relative loss given the higher number of parliamentary offices available per member state following the UK’s withdrawal.

citer l'article

François Hublet, 10 Key Lessons of the 2024 European Parliament Election, Jan 2025,

à lire dans cette issue

voir toute la revue