General elections in Bosnia and Herzegovina, 2 October 2022

Damir Kapidžić

Associate Professor at University of SarajevoIssue

Issue #3Auteurs

Damir Kapidžić

Issue 3, March 2023

Elections in Europe: 2022

Introduction

Bosnia and Herzegovina’s (BiH) elections are among the world’s most consistent. The ninth general election in Bosnia and Herzegovina since the end of the Bosnian War in 1995 was held on 2 October 2022. Under the intricate system of governance established by the Dayton Peace Agreement, elections were held for three levels of government. Voters could cast their votes in up to four election contests, depending on their place of residence. These include a tripartite presidency at the state level, 13 parliaments at three distinct levels — national, subnational, as well as local in the subnational entity Federation of Bosnia and Herzegovina (FBiH) —, and a subnational presidency election in the Republika Srpska (RS) entity.

For these elections the Central Electoral Commission approved 72 political parties, 38 coalitions, and 17 independent candidates for a total of 7257 candidates. The elections were called exactly four years after the previous elections in 2018 in line with the constitution and electoral law. However, in the lead-up to the election, there was much uncertainty regarding anticipated and much-needed changes to the electoral law, as well as political infighting over budgeting for elections. Election day was orderly with minor infractions that were addressed in line with laws and regulations. The counting of ballots, however, took more time, and several recounts were performed. The official results were confirmed one month after the elections, as per law.

The political and electoral system of Bosnia and Herzegovina

The country has a complex political system with a multiethnic population divided along religious lines: Catholic Croats, Muslim Bosniaks, and Orthodox Christian Serbs. The current system of governance places an emphasis on ethnic representation in institutions through a consociational model of democracy. It was created in 1995 following the Bosnian War and is part of the Dayton Peace Agreement, guaranteeing power-sharing and distribution of political offices along ethnic lines, as well as power-sharing between the national and subnational (or entity) levels of governance. The resulting electoral competition reinforces ethnic cleavages by emphasizing both the declared and perceived ethnicity of candidates, political parties, and voters. The electoral system of BiH consists of open list proportional representation for national, subnational, and local parliaments, and first-past-the-post contests for directly elected national and subnational presidents and mayors. Both the political and electoral system of BiH is heavily influenced by ethnic politics and the ethno-territorial distribution of the population. A peculiar element of the BiH political system is the Office of the High Representative, created to ensure civilian implementation of the peace agreement. The Office, and its current holder Christian Schmidt, have vast powers to make laws, veto legislation and dismiss officials, often compared to those of a viceroy.

The national level of government has limited competences and includes a directly elected three-member presidency consisting of one Serb member from the RS, and one Bosniak and one Croat member from the FBiH. The candidates run on separate ethnic lists, which discriminates against cCitizens not identifying with one of these three ethnic groups are excluded from running. The ballot in RS lists only Serb candidates with the winner decided by simple majority. In FBiH the Bosniak and Croat candidates are on the same ballot separated into two ethnic lists and voters have one vote. The winner is decided by simple majority on each list. The bicameral BiH Parliament consists of a 15-member House of Peoples whose members are equally distributed among the three ethnic groups and appointed by subnational parliaments, and the 42-member House of Representatives, whose members are elected from eight multimember districts (14 in three districts from RS; and 28 in five districts from FBIH). Only 30 members are elected directly through open-list PR, with a district size ranging from three to six members, while the remaining 12 seats are compensating seats awarded at the entity level to ensure proportionality of the vote and representation of parties whose support is dispersed (Kapidžić & Komar 2022). At the electoral district level, a 3% electoral threshold is applied with seats allocated using the Sainte-Laguë method, which also applies for subnational and local elections (Election Law of Bosnia and Herzegovina 2022). This low electoral threshold and method of distribution are designed to favor smaller and regional parties, which results in a highly fragmented legislature.

On 2 October 2022, concurrent elections were held for parliaments and offices at up to three levels of government. Voters in the FBiH could vote for either a Croat or Bosniak member of the BiH Presidency, the House of Representatives of the BiH Parliament, the 98-member subnational House of Representatives of the FBiH Parliament, and one of ten local Cantonal Assemblies. Voters in the RS cast their vote for the Serb member of the BiH Presidency, the House of Representatives of the BiH Parliament, the President (or vice-presidents) of the RS, and the 83-member subnational RS National Assembly. At most of these levels, the previous administration was made up of ethno-nationalist parties and leaders who were hesitant to work together and establish shared policies during their tenure, especially those related to constitutional and electoral change. Concurrent elections produced very similar outcomes across electoral contest at different levels of government and the analysis will focus on the contest at the national level.

Turnout, parties and ethnoterritorial voting patterns

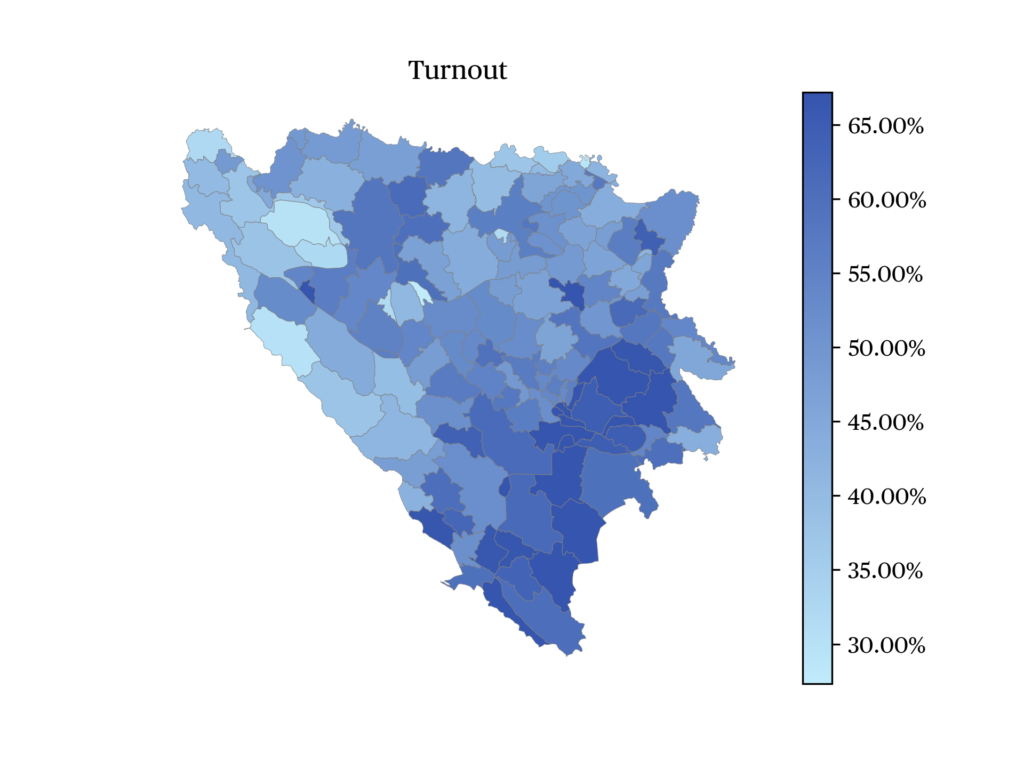

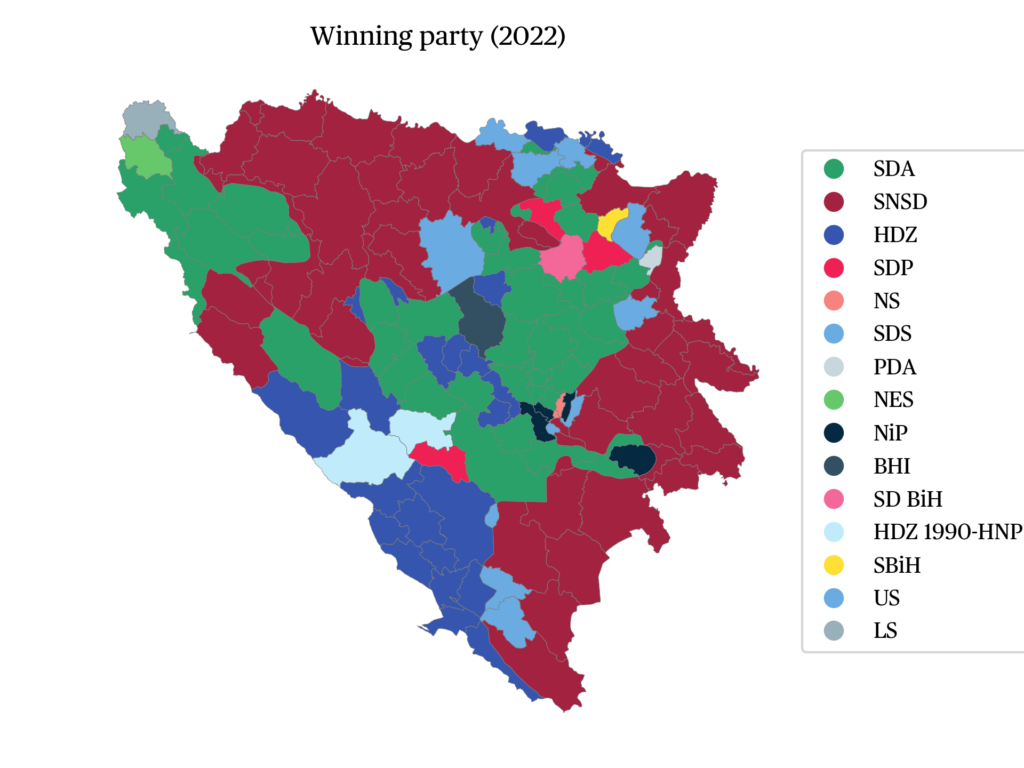

The turnout was 51.5%, slightly lower than in the previous elections (54% in 2018), with almost 80.000 less votes cast. Turnout was lower in municipalities in the northwest of the country that have experienced a larger rate of emigration, and higher in the east and southeast (see Figure a). Electoral competition is largely confined within ethnic party subsystems, among parties that represent one of the three main ethnic groups. The Party for Democratic Action (SDA), People and Justice (NIP), and the People’s European Union (NES) are the most significant ethnic parties among Bosniaks in these elections. For Serbs they are the Alliance of Independent Social Democrats (SNSD), the Serb Democratic Party (SDS), and the Party of Democratic Progress (PDP). Among Croats it is the Croatian Democratic Union of Bosnia and Herzegovina (HDZ BiH), and the Croatian Democratic Union 1990 (HDZ 1990). There are also multi-ethnic parties that regularly win a sizeable portion of the vote, but they mostly vie Bosniak voters. The Social Democratic Party (SDP), Democratic Front (DF), and Our Party (NS) are the most significant.

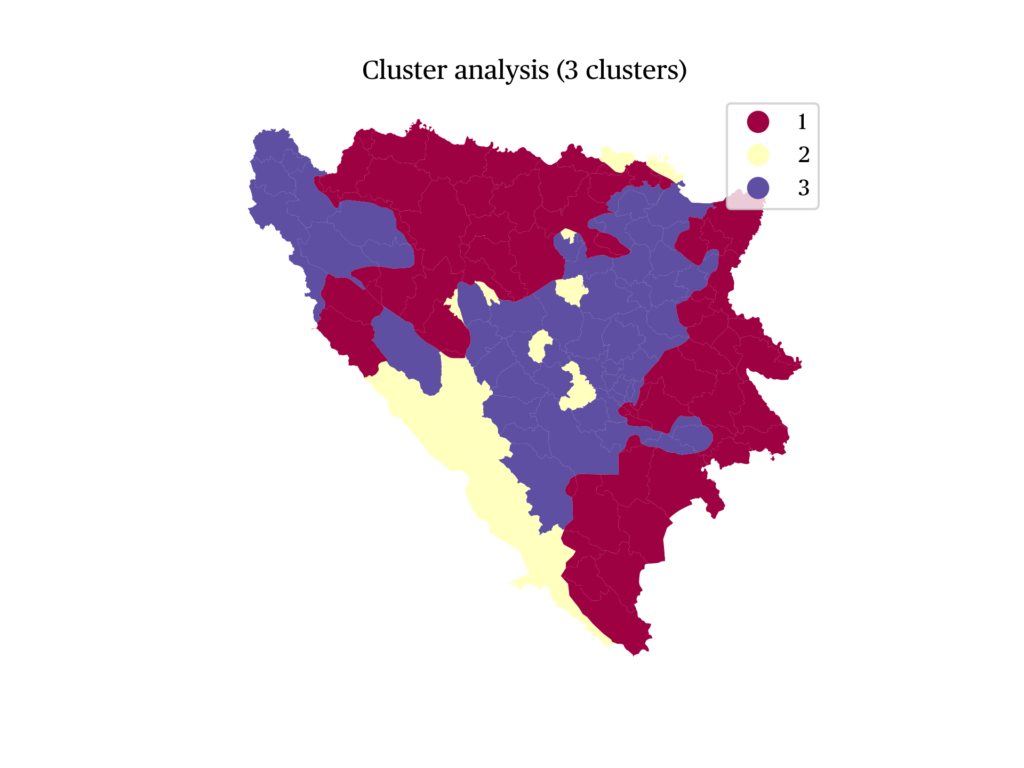

Even though there has been intense competition within ethnic party subsystems throughout the previous eight electoral cycles, hardly any voters have switched from one ethnic party to another (Kapidžić & Komar 2022). The majority of electoral competition is contained within the ethnic party subsystems. Bosniak parties compete among themselves for Bosniak votes, Serb parties for Serb votes, Croat parties for Croat votes, and multi-ethnic parties for secular (and some Bosniak) votes. As ethnic groups are territorially concentrated and most areas have a clear ethnic majority, this results in ethno-territorial patterns of competition that can be grouped into three clusters (see Figure b). A principal component analysis of election results at the municipal level confirms a domination of Serb parties in the RS, and Croat parties in Herzegovina (the country’s south), as well as individual municipalities. Bosniak parties have a strong show in central FBiH and in the northwest. Essentially, party support is territorialized segmented along ethnic lines, without significant impact of other socio-demographic variables. This has not changed in the 2022 elections, except for a shift in two municipalities where Croat parties lost their majority to Serb parties (Bosansko Grahovo) and Bosniak parties (Busovača), most likely due to increased Croat emigration.

Post-election drama

During election day there were a few minor incidences of electoral irregularities, but no significant setbacks. After the polls closed at 7 o’clock, everything changed when the High Representative Christian Schmidt made a public speech on election night announcing that he would enforce new amendments to the Election Law and the subnational Constitution of the Federation of Bosnia and Herzegovina. The changes did not affect the votes for direct contests that citizens had just cast but introduced changes to FBiH’s indirectly elected upper chamber of Parliament. Although the verdict decision addressed longstanding issues that benefit the functioning of FBiH, the timing could not have been worse. After casting their ballots, voters in FBiH were shocked uneasy to learn that their vote might (indirectly) affect how the FBiH Parliament is constituted. The full implications of the decision in relativizing democratic elections and for government formation and decision-making are still uncertain.

Vote counting proceeded very slowly and was plagued by delays and irregularities at the polling station level. Several municipalities had to do recounts to confirm results, due to mistakes in reporting or close contests. In the RS, the vote for the subnational President of RS went into a full recount amidst allegations of fraud and significant irregularities by the united opposition candidate Jelena Trivić (PDP), against incumbent Milorad Dodik (SNSD). After the recount was completed, the initial projection of Dodik’s win was confirmed, but with a smaller margin. The Central Electoral Commission confirmed the results one month after the elections on 2 November 2022, after the Court of BiH rejected all outstanding appeals.

Winners and losers

The first votes counted and confirmed were for the three members of the Presidency. Željka Cvijanović (SNSD) won against Mirko Šarović (SDS) and other Serb candidates, thus retaining the office for her party. Cvijanović will become the first female President of Bosnia and Herzegovina. Even though the role is largely ceremonial, she is expected to continue the policy of weakening central institutions to benefit the subnational RS. Voters elected Denis Bećirović (SDP) as the Bosniak member of the Presidency against Bakir Izetbegović (SDA) and Mirsad Hadžikadić (Platform for Progress). Bećirović is the first Bosniak nominated by a multiethnic party with support from a broad coalition of Bosniak and civic-oriented parties. His victory was a big upset for Izetbegović, the party leader of the conservative SDA that has held the office for the past three terms. The incumbent Croat member Željko Komšić (DF) won against Borjana Krišto (HDZ BiH), largely with support of non-Croat voters and after not having campaigned at all in Croat-majority areas. This is his fourth, but non-consecutive, term in office and his repeated victories have long been a thorn in the eyes of Croat ethnic parties. With two members of the Presidency coming from non-ethnic parties this could bring a new dynamic into the office.

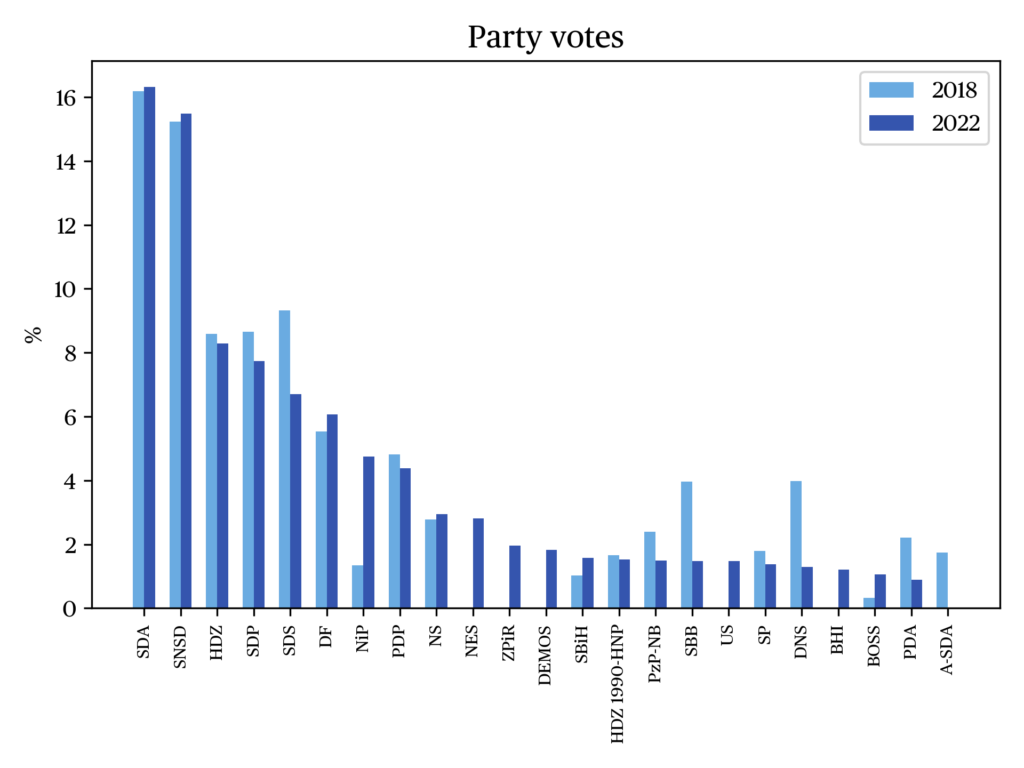

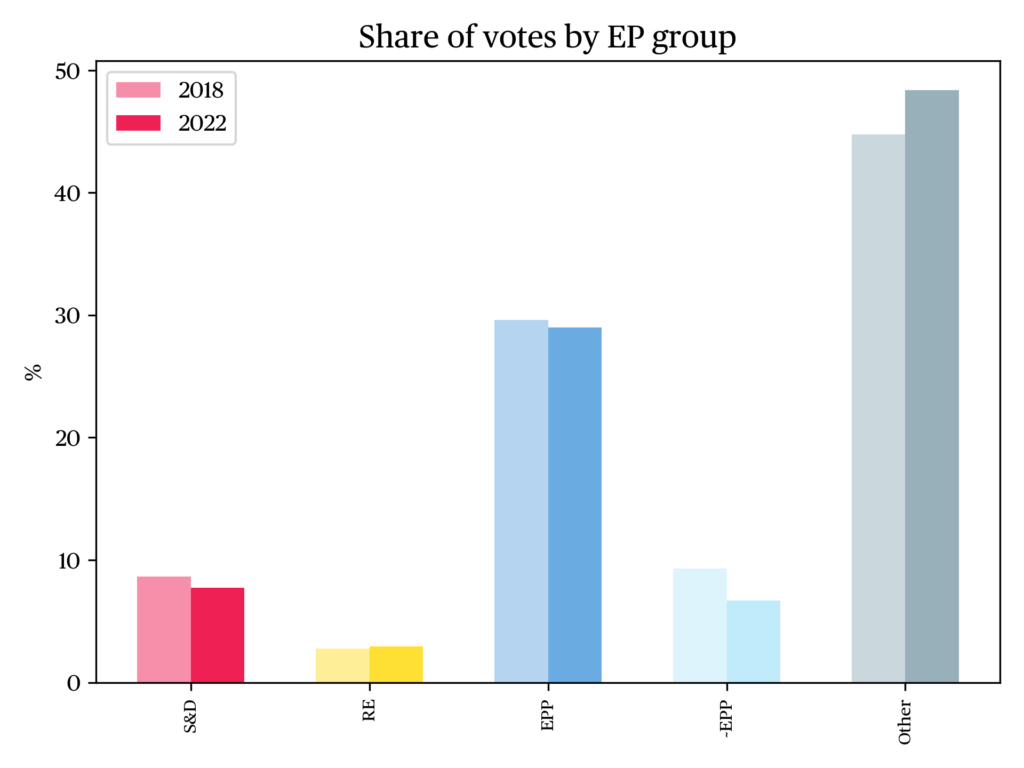

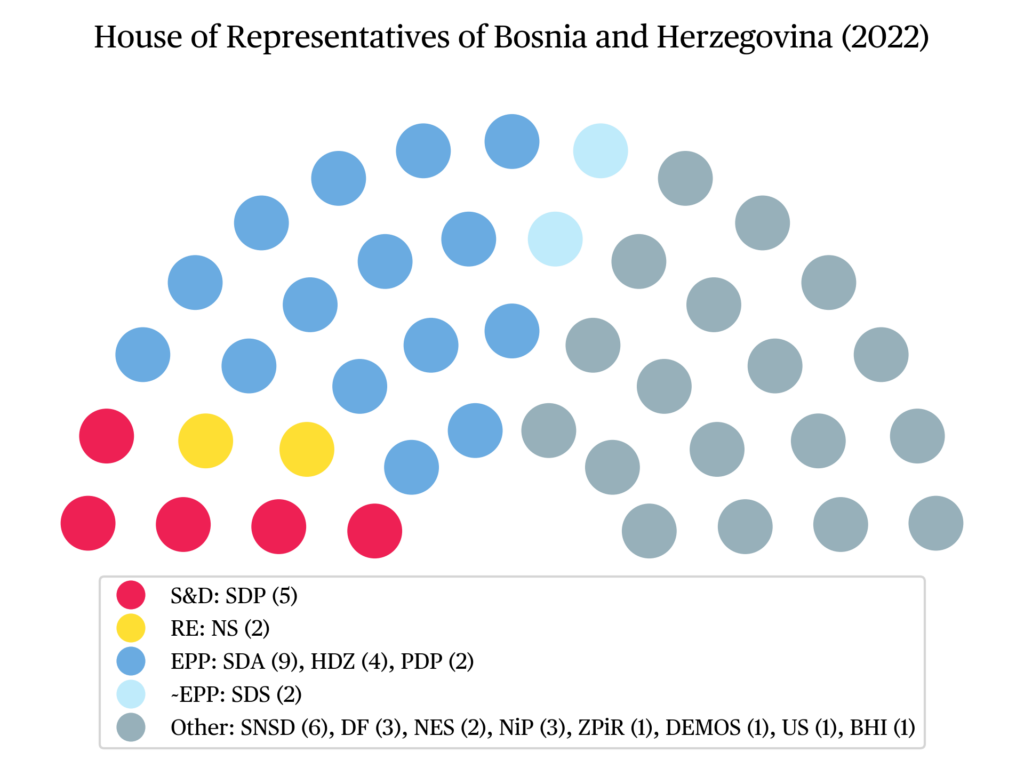

It is necessary to look at the results for the House of Representatives of the BiH Parliament both along ethnic party subsystems, and incumbent vs. opposition dynamics. The results indicate a strong and stable performance of the main incumbent Croat, Serb, and Bosniak parties, HDZ BiH, SNSD, and SDA, respectively (see panel “the data”). These largely managed to hold on to their share of votes and seats. HDZ is the only Croat party in Parliament and will play a key role in government formation. A slight decrease of vote share and seats for members coming from Croat parties is however noticeable. It is worth exploring whether this is due to higher emigration levels of BiH Croats towards the EU who, as Croat passport holders, hold EU citizenship.

The SNSD increased its dominant position in Parliament, while keeping the same number of seats. This is mainly because Serb opposition parties, SDS and PDP, lost votes. With now six Serb parties in Parliament, the opposition’s voice is splintered and weakened, which benefits the incumbent SNSD as it will be difficult avoid including them in governance. The three multiethnic, SDP, DF, and NS, parties managed to maintain their seats with minor changes in vote percentage. Among Bosniak parties the SDA was held on to its votes and seats but is still the big loser of the elections. This is largely due to a shift towards a more unified opposition of Bosniak parties in Parliament, led by NIP and NES (see panel “the data”). Together with some of the multiethnic parties this Bosniak opposition could bypass the SDA in government formation, despite the SDA having the most members of Parliament of any political party.

A fragmented Parliament and government formation

In order to form government at the national level, a coalition of Croat, Serb and Bosniak (and possibly multiethnic) parties is required under the consociational power-sharing system. This will be difficult to achieve as the Parliament remains highly fragmented with 14 parties, a consequence of a low electoral threshold and the Sainte-Laguë method. It is not certain that the largest three ethnic parties will come together. Government will likely include HDZ BiH and SNSD as they hold the majority in the upper chamber, the House of Peoples, where votes are needed to confirm government and pass legislation. However, Bosniak opposition and multi-ethnic parties have joined forces to oust the SDA out of government. Together with the Croat HDZ, eight multiethnic and Bosniak parties have signed a programmatic coalition agreement at the subnational level in the FBiH, which is seen as a precursor to forming a coalition at the national level. With the Presidency dominated by members from multiethnic parties, this might signal a nascent shift away from exclusive ethnic politics in BiH.

References

Kapidžić, D. & Komar, O. (2022). Segmental Volatility in Ethnically Divided Societies: (Re)Assessing Party System Stability in Southeast Europe. Nationalities Papers, 50(3), 535–553.

Election Law of Bosnia and Herzegovina (Unofficial consolidated text) (2022). Central Electoral Commission of Bosnia and Herzegovina. Retrieved 14.11.2022.

citer l'article

Damir Kapidžić, General elections in Bosnia and Herzegovina, 2 October 2022, Mar 2023, 161-165.

à lire dans cette issue

voir toute la revue