Parliamentary and presidential elections in Romania, November-December 2024

Issue

Issue #5Auteurs

Sorina Cristina Soare , Claudiu D. Tufiș

Issue 5, January 2025

Elections in Europe: 2024

Romania’s post-communist electoral history has been marked by remarkable chronological stability. Both parliamentary and presidential elections have consistently occurred at the natural conclusion of their respective electoral cycles. During this time, Romania held ten legislative and nine presidential elections. Following the volatility of the early 1990s, this pattern of regularity was further consolidated by a relatively closed party system, characterized by predictable competition for governmental power and routinized inter-party relations (Casal Bértoa & Enyedi, 2021). More specifically, under various names and in different configurations, a small group of parties, the Social Democratic Party (PSD), the National Liberal Party (PNL), and the Democratic Alliance of Hungarians in Romania (UDMR), maintained continuous parliamentary representation and played central roles in forming governing coalitions. This entrenched dominance was mirrored in presidential politics, where electoral runoffs consistently featured the PSD candidate opposing a center-right, anti-communist challenger, typically allied with or eventually incorporated in the current PNL.

However, political competition increased over time: the combined vote share of mainstream parties in the Chamber of Deputies has declined from 90% in the 2008 elections (the first held after Romania’s accession to the European Union), to 89% in 2012, 72% in 2016, and just 61% in 2020. Simultaneously, the presence and influence of challenger parties, ranging from progressive reformists to traditionalist and nationalist actors, have expanded. While none of these parties gained parliamentary representation in 2008, their cumulative vote share rose to 14% in 2012, 9% in 2016, and 25% in 2020.

The year 2024 was expected to follow this trajectory of increasingly pluralistic yet institutionally stable electoral politics, broadly aligned with the prevailing political direction of the European Union (EU). It was anticipated as a “mega-electoral” year, including all four major elections: local and parliamentary elections (held every four years) and presidential and European Parliament elections (held every five years). This rare alignment, occurring once every two decades, happened for the first time since Romania’s accession to the EU in 2007. But what began as a promising opportunity to test the resilience of Romania’s democratic institutions and its pro-EU orientation quickly deteriorated into a major political turmoil.

The elections were overseen by a PSD-PNL coalition government, which initially appeared capable of managing the electoral calendar without surprises. The local and European Parliament elections were held on 9 June 2024. Although largely uncontroversial, they produced one major surprise: the emergence of SOS România, a recently created party that secured representation in the European Parliament (EP). Its political agenda echoed nativism, authoritarianism, and populism and reflected the increased appeal of radical right-wing populism in contemporary politics (Mudde, 2007). The party, led by Diana Șoșoacă, made its mark on Romanian politics with an aggressively vocal style. Its rhetoric was characterized by anti-vaccination conspiracies, openly anti-NATO and anti-EU positions, and regular antisemitic remarks. Significantly, the party’s electoral breakthrough owed much to support from Romanian diaspora. Despite receiving only 4.83% of the vote at the national level (slightly below the electoral threshold), the 28,457 votes cast for the party by overseas voters were enough for it to secure representation in the EP.

What started as a routine electoral cycle rapidly devolved into a highly polarized and destabilizing sequence of events. Romania was thrust into a major political crisis, on top of the ongoing external threat posed by Russia’s war on Ukraine and mounting concerns over a looming economic downturn. In this context, the 2024 elections underscore the dynamics of what V. O. Key (1955) famously termed “critical elections”, electoral moments marked by exceptionally high levels of voter mobilization and public concern. In the Romanian case, the critical nature of the 2024 electoral cycle extended beyond these core features. It was also characterized by intensified political engagement from a heterogeneous range of domestic actors (e.g., political parties, political leaders, intellectuals, influencers, and civil society organizations), as well as international actors (including non-resident Romanian voters, foreign political influencers, third countries, and high-ranked politicians). As such, what underscores the critical dimension of these elections is both the intensity of political mobilization and a fundamental reconfiguration of the country’s underlying political cleavages. Indeed, the 2024 electoral sequence revealed the consolidation of a new and deeply polarized political alignment, one likely to persist and shape the contours of electoral competition for the foreseeable future.

Structural Constraints, Contextual Shocks, and the Rise of Challenger Parties

How did Romania end up in this unpleasant situation? The answer can be traced to both long-standing structural characteristics of its party system and to the accumulation of external and internal stresses that have fed public discontent and a new political supply. At the core of these tensions lies a constrained political opportunity structure, marked by limited alternance in government and a growing mismatch between political supply and societal demand.

Romania’s post-accession period has been characterized by an increasingly open yet structurally rigid party system. The government composition and agenda-setting have been monopolized by two dominant parties, the PSD and the PNL. This alliance has led to a form of constrained alternance, limiting both innovation and substantive policy reform. This monopolistic configuration in government was counterbalanced by a gradual erosion of trust in traditional parties and the emergence of new political actors with a challenger profile (De Vries and Hobolt, 2020), which have been able to capitalize on the shortcomings of the mainstream parties.

The Save Romania Union (USR), which entered Parliament in 2016, and the Alliance for the Union of Romanians (AUR), which did so in 2020, exemplify this phenomenon. Both parties deploy a form of anti-establishment rhetoric aimed at delegitimizing conventional political elites while amplifying their own narratives, centered on an anti-corruption pledge for USR and national identity and conservative values for AUR. Although ideologically divergent, USR and AUR share important structural similarities. They both emerged from segments of civil society (Grama, 2025), and their political style reflects a rejection of established parliamentary norms. Their use of disruptive tactics, including public protests within Parliament, sit-ins, and symbolic confrontations, represents a deliberate challenge to ‘politics as usual’ and a break with the informal norms that mainstream political parties developed over the years for negotiating and cooperating.

Beyond these political aspects, the 2020–2024 period has been marked by a series of destabilizing contextual shocks that have further undermined the legitimacy of established political actors. The 2020 parliamentary elections, held amidst the COVID-19 pandemic, resulted in the lowest voter turnout in post-communist Romanian history (32%), raising concerns about the representative legitimacy of the resulting government. The coalition formed between the PNL, USR, and UDMR proved short-lived, collapsing within a year due to intra-coalitional conflicts, particularly between the PNL and USR. As the negotiations for the new coalition were proceeding, the threat of Russia invading Ukraine, Romania’s neighbor, helped the parties reach an agreement on a new coalition government, composed of the PSD, PNL, and UDMR, which governed until the 2024 elections. This pragmatic but ideologically incongruous arrangement further blurred the lines between opposition and government, weakening the capacity of voters to clearly identify alternatives and eroding democratic responsiveness. Thus, by the beginning of 2022 the only parliamentary opposition was composed of the USR, which was part of the governing coalition during 2020-2021, and AUR, whose radical discourse increasingly occupied the space vacated by discredited mainstream narratives.

The pandemic imposed severe public health restrictions and triggered a broader economic downturn. The war in Ukraine compounded these challenges: concerns over energy insecurity and the significant influx of Ukrainian refugees placed additional pressure on Romania’s already fragile public services and welfare infrastructure. Despite positive macroeconomic indicators in recent years, Romania consistently ranks among the worst-performing EU member states on key social indicators, particularly those relating to poverty risk, material deprivation, and inequality (Borțun, 2025). The perceived disconnect between headline economic growth and lived material conditions has generated widespread disillusionment with the post-socialist economic model, which has largely adhered to market-liberal orthodoxy, associated with the precarization of labor, underfunded public services, and insufficient social protection.

The mega-electoral year

As the government was starting to prepare the 2024 elections, the main parties in power, the PSD and PNL, realized that they would have to pay a high price for governing during a polycrisis. As a result, they started worrying about their performance in the upcoming elections. Based on the dates of the previous elections, the 2024 electoral calendar should have started with the elections to the European Parliament (EP, in June) and continued with local elections (in September), presidential elections (in November), and parliamentary elections (in December). Afraid of underperforming in the EP elections (second-order elections usually have rather low turnout), the PSD and PNL sought to capitalize on the mobilizing power of their mayors by organizing both local and EP elections the same day, on June 9. The decision has been criticized by civil society organizations and the opposition and has been interpreted as an attempt to minimize the votes obtained by challenger parties (Pârvu, 2024).

During the electoral campaign for the local and EP elections, the PSD and PNL adopted a strategic focus on local governance issues, seeking to consolidate their electoral base by emphasizing the administrative performance of their incumbent mayors. This strategy was consistent with their objective of maximizing returns in the local elections. Smaller parties chose to differentiate themselves by emphasizing issues beyond the local level (Tufiș 2024): in contrast to the local-focused approach of the main parties, the USR, the People’s Movement Party (PMP), and several former USR Members of the European Parliament (MEPs) running as independents prioritized the European agenda during their campaigns. Their strategy aimed at increasing their visibility and electoral share in the European contest. By emphasizing topics such as rule of law, a green economy, democratic accountability within EU institutions, and the future of EU integration, these actors positioned themselves as pro-European reformists, seeking to reclaim relevance in a fragmented political landscape.

At the opposite end of the spectrum, AUR and SOS România adopted a Eurosceptic and nationalist discourse, focusing on a critical reassessment of Romania’s relationship with the EU. Their rhetoric appealed to voters dissatisfied with the perceived erosion of national sovereignty, as both parties framed the EP elections as an opportunity to ‘put Europe in its place’ (Ioana, 2024). While AUR did not question Romania’s EU membership, their discourse nonetheless mirrored the broader repertoire found across Central and Eastern Europe, emphasizing cultural protectionism and the defense of national identity. More radically, the leader of SOS România introduced a discourse that directly questioned Romania’s future within the EU. While this position remains marginal in the Romanian political mainstream and has rarely been subject to serious debate, its emergence marks a significant discursive shift, suggesting that hard Euroscepticism, though still peripheral, is becoming more vocal within the public sphere (Soare, 2024).

The official results of the EP elections (Biroul Electoral Central, 2024) showed that the strategy was not entirely successful. While the PSD and PNL obtained the same number of seats as in the 2019 elections, the extremist parties, AUR and SOS România, managed to get almost 20% of the vote and to send eight members in the European Parliament (the six AUR MEPs joined the European Conservatives and Reformists Group, ECR, while the two SOS România MEPs remained non-attached). After four years of isolation in the Romanian Parliament, AUR came out of the EP elections as the second most important Romanian party in the EP, a position that increased its appeal among some of the voters.

AUR’s performance in the 2024 local elections tells a different story. As a relatively new political formation, AUR lacks the organizational strength typically required to achieve electoral success in local contests. Unlike national or European elections, where the party leader and media visibility can compensate for organizational deficits, local elections in Romania are significantly shaped by institutional and structural constraints that tend to favor entrenched actors. One of the key institutional barriers is the first-past-the-post electoral system used to elect mayors and presidents of county councils. This electoral design tends to amplify the advantages of incumbency, rewarding candidates who benefit from name recognition, established patronage networks, and local party organizations. As such, new parties like AUR often struggle to gain traction in local races, where electoral outcomes are less determined by national narratives and more by local power dynamics.

Additionally, the political economy of local governance in Romania amplifies these difficulties. Local administrations remain heavily dependent on central government funding, often distributed according to partisan criteria. This structural dependency creates strong incentives for local candidates to align with governing parties, as access to central funds can significantly influence local development prospects. Last-minute party switching where local candidates abandon smaller or opposition parties in favor of those in government is a recurrent feature of local electoral politics in Romania. Such dynamics further disadvantage parties like AUR that lack access to state resources or established patronage channels. SOS România, whose performance in the 2024 local elections was also modest, faced similar challenges. Together, the PSD and PNL won about 60% of the contests (county council presidents, county councilors, mayors, local councilors), while AUR came on the fourth place in the mayoral races and on the third place for county councilors (10.7% of the votes) and local councilors (9.5% of the votes).

The second part of the 2024 electoral cycle in Romania unfolded as an almost uninterrupted campaign, stretching from the spring local and EP elections into autumn. This prolonged mobilization period created an intense political climate, marked by sustained partisan activity in the media and voter exposure to repeated electoral messaging. Over the summer, campaign efforts intensified rather than subsided, contributing to a sense of electoral fatigue among both voters and political actors.

A key feature of this second electoral sequence was the temporal overlap between the parliamentary and presidential campaigns, which led to a significant imbalance in public and political attention. Despite the institutional significance of the parliamentary elections, the dominant focus of both parties and the electorate was on the presidential race, which commanded greater visibility and symbolic weight. This dynamic resulted in the parliamentary elections being overshadowed, with lower salience and strategic engagement compared to the presidential contest.

The parliamentary elections took place on December 1, following a subdued campaign period during which political parties, their candidates, and platforms attracted limited public attention. The turnout rate increased significantly with respect to the parliamentary elections of 2020, from almost 32% to slightly over 52%, explained both by the fact that the 2020 elections were held during the pandemic and by the highly polarized political context in 2024.

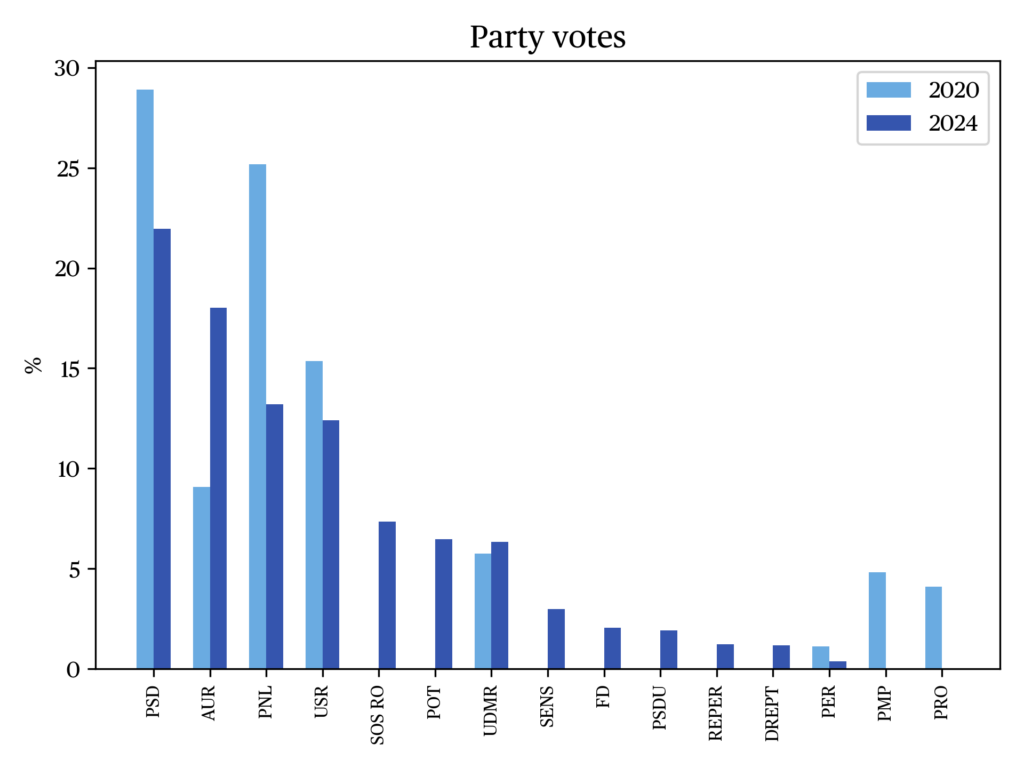

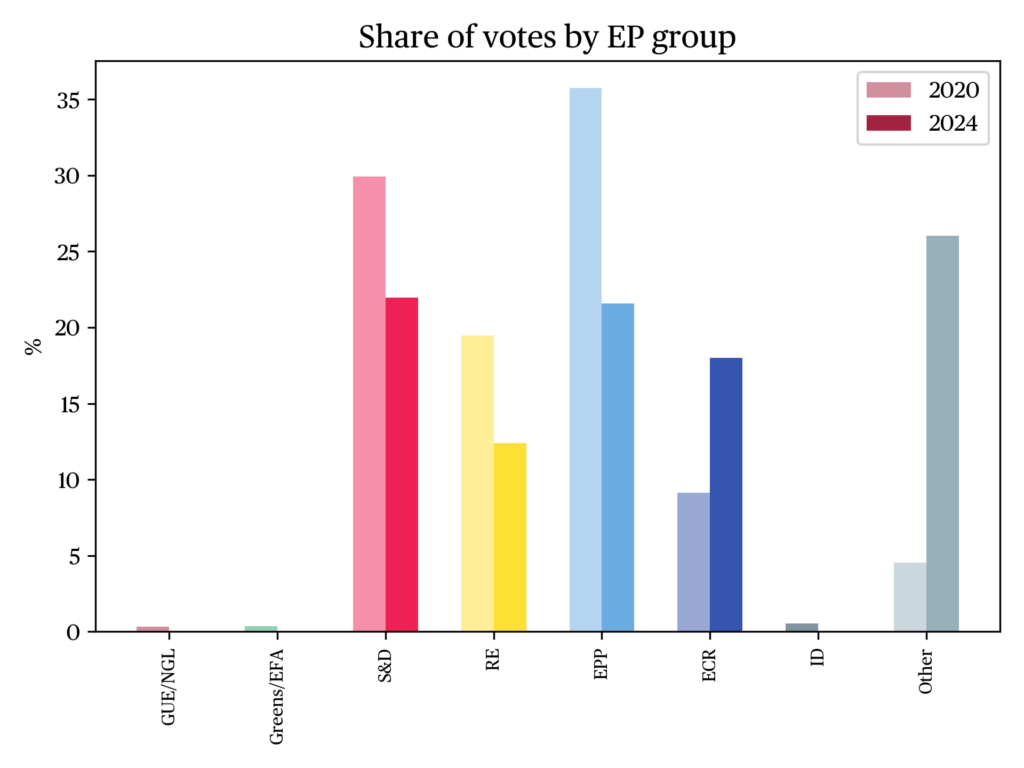

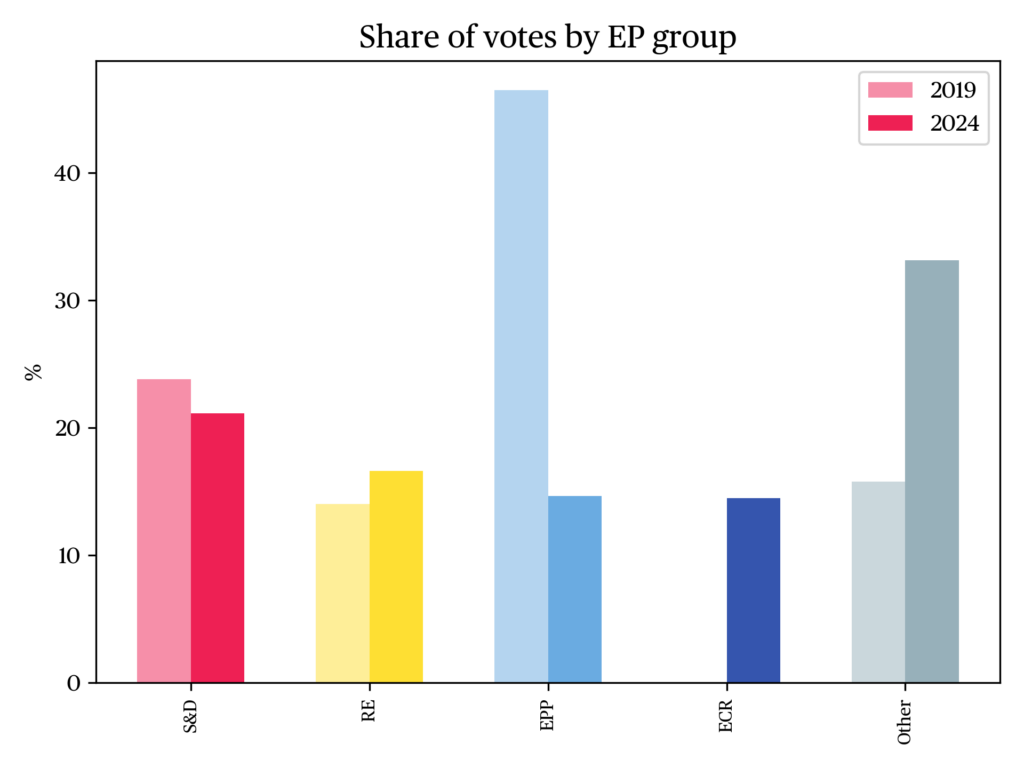

The results offered a clear verdict on the prevailing mood throughout the year: widespread voter discontent with the governing parties, primarily the PNL–PSD coalition. This electoral backlash was fueled by a range of grievances. For some, the government’s handling of the pandemic remained a source of frustration; for others, Romania’s foreign policy alignment with Ukraine provoked criticism; economic performance, particularly the persistence of inequality and precariousness, also figured prominently; and a notable portion of the electorate expressed anger over the PNL’s decision to form a governing coalition with the PSD in 2022, an act perceived as betraying prior commitments to political renewal. These diverse sources of discontent converged into a unified electoral response: a punitive vote against the parties in power. These dynamics are reflected clearly in the data presented in Figure a, which compares the results of the 2024 parliamentary elections with those of 2020.

| Political party / alliance | 2024 votes (%) | 2020 votes (%) | 2024-2020 difference |

| Social Democratic Party – PSD | 21.96% | 28.90% | -6.94 |

| Alliance for the Union of Romanians – AUR | 18.01% | 9.08% | +8.93 |

| National Liberal Party – PNL | 13.20% | 25.19% | -11.99 |

| Save Romania Union – USR PLUS | 12.40% | 15.37% | -2.97 |

| SOS România – SOS RO | 7.36% | – | +7.36 |

| Party of Young People – POT | 6.46% | – | +6.46 |

| Democratic Alliance of Hungarians in Romania – UDMR | 6.33% | 5.74% | +0.59 |

| Other parties / candidates | 12.45% | 13.15% | -0.70 |

| Cancelled votes | 1.83% | 2.57% | -0.74 |

Data source: Romanian Permanent Electoral Authority.

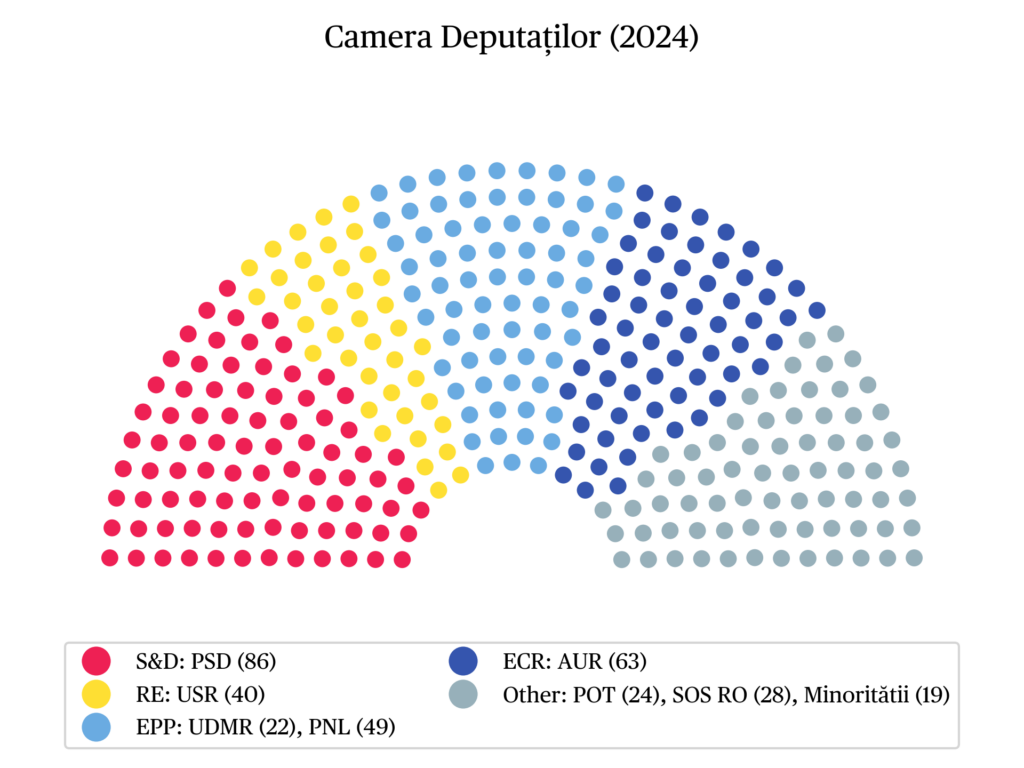

The main governing parties, PSD and PNL, lost a combined 19% of the vote compared to 2020. This loss confirms the depth of public disaffection with the political establishment and validates the interpretation of the 2024 elections as a punishment vote targeting those in power. The UDMR, which primarily represents the Hungarian-speaking minority and draws strong support from majority-Hungarian regions in Transylvania, benefited from a highly disciplined electorate. It successfully increased turnout within the Hungarian community to keep pace with the expected rise in overall voter participation. The USR, despite not being part of the ruling coalition at the time of the elections, also experienced a modest decline, losing nearly 3% of the vote compared to its 2020 performance. This underperformance can be attributed to internal party conflicts, leadership struggles, and the public perception that USR bore partial responsibility for the collapse of the 2020 governing coalition (Dumitrescu, 2024). Despite these significant electoral losses, the post-election power balance remained largely unchanged. The two main parties were able to reconstitute their governing coalition, once again joined by the UDMR and with the support of the parliamentary group representing national minorities. This continuity underscores the structural inertia of coalition politics in Romania, where electoral setbacks do not necessarily produce a change in the dynamics of political power. Despite significant losses at the ballot box, the main parties remain capable of retaining control over government formation through elite negotiations.

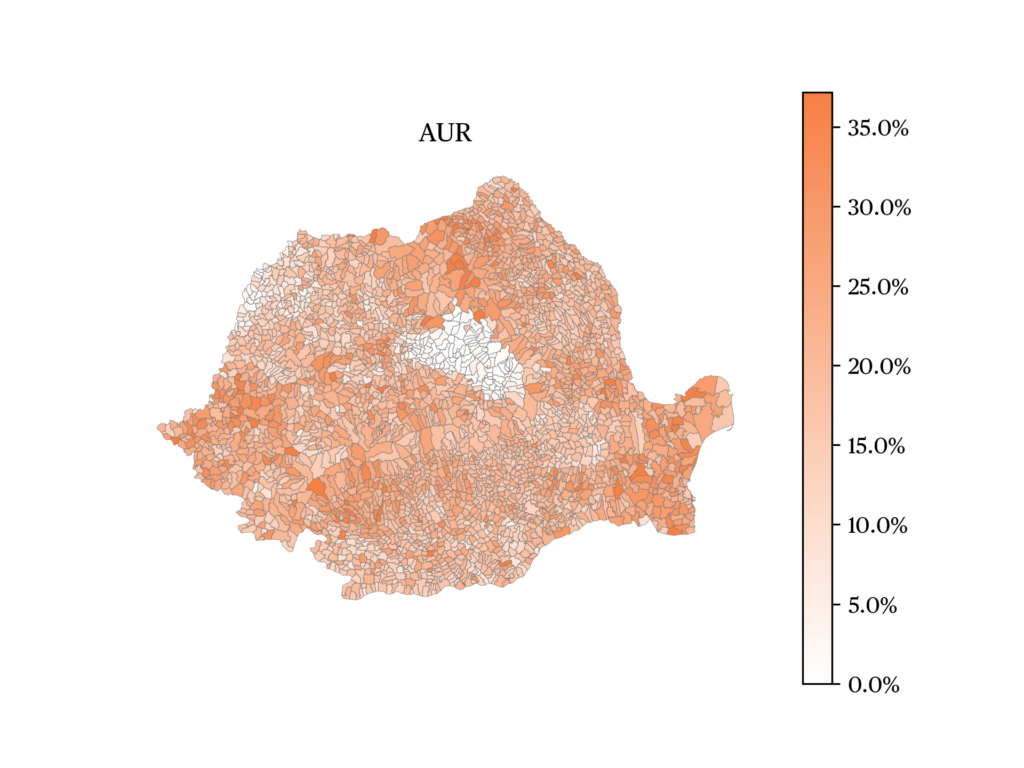

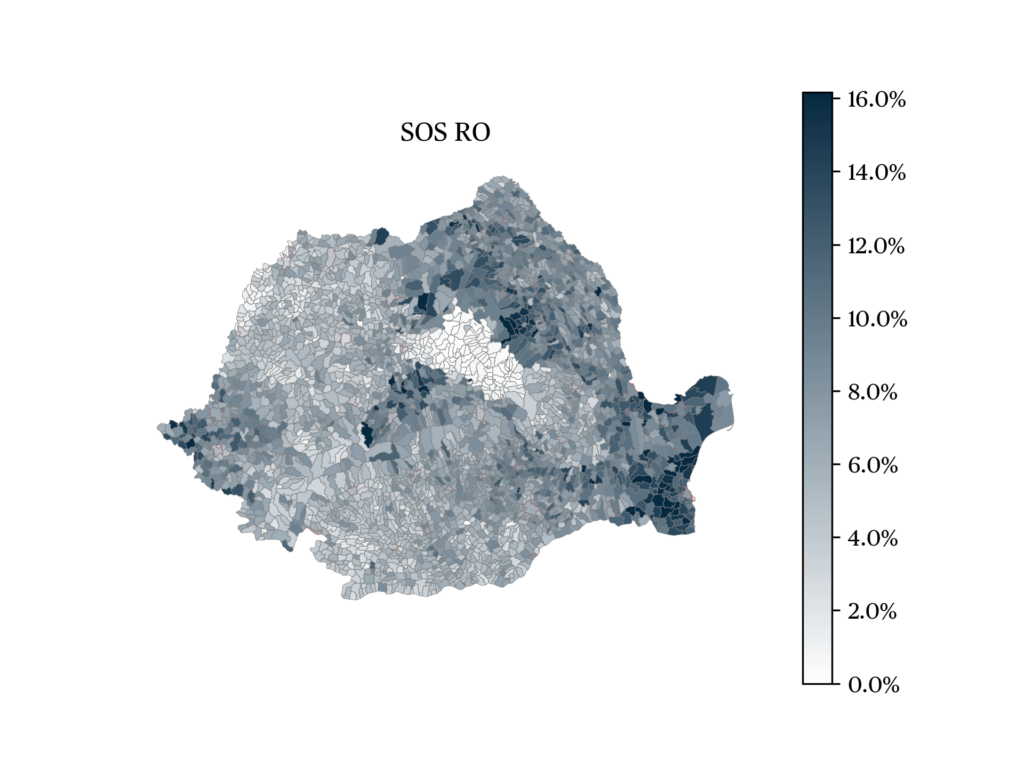

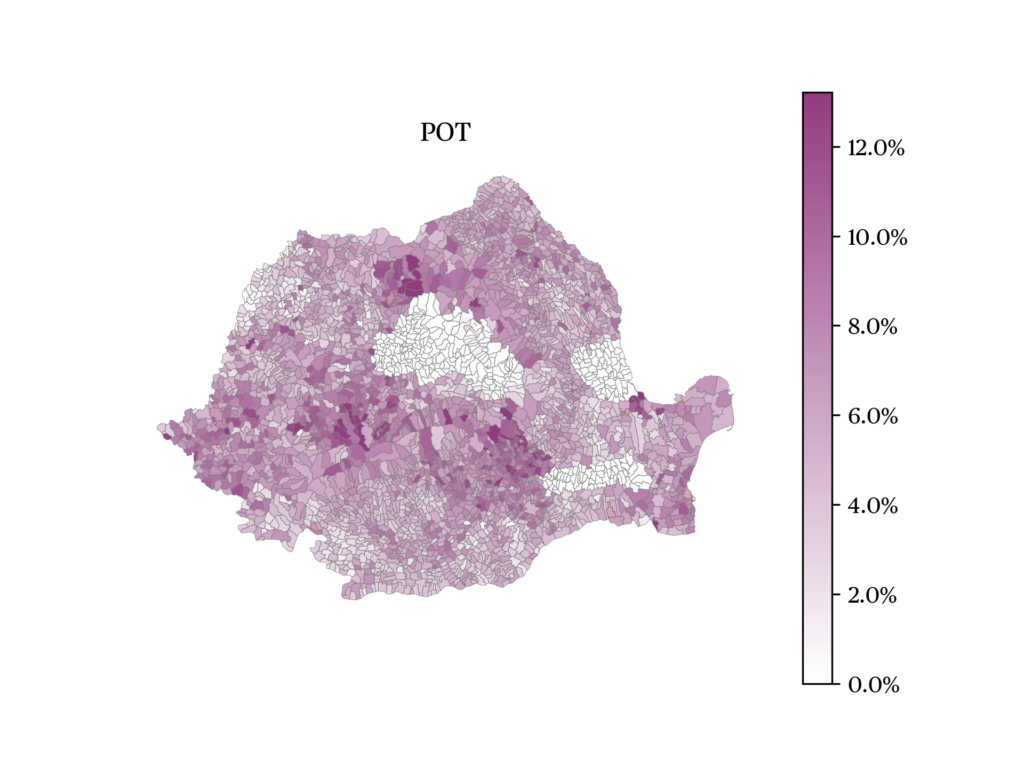

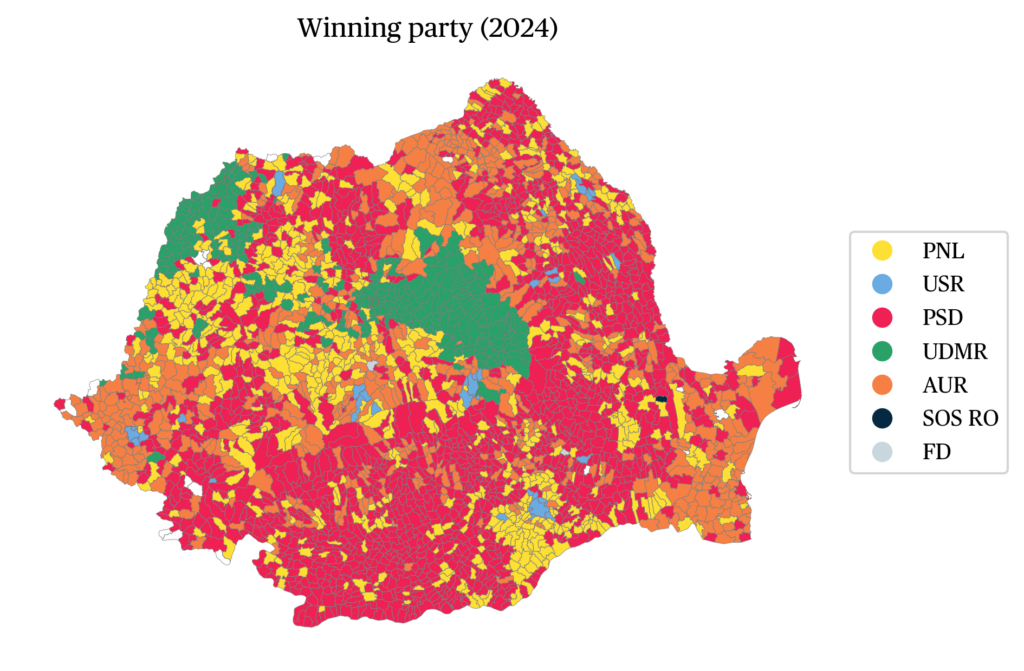

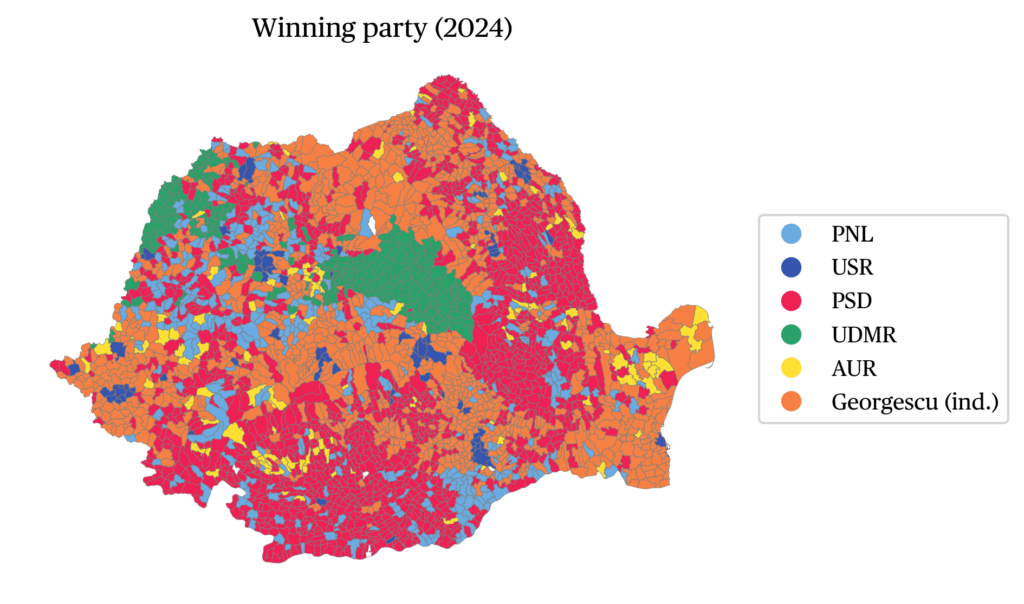

The upholding of the cordon sanitaire policy against populist radical right parties has emerged as a second major axis of continuity in Romanian politics. While this informal barrier against radical or anti-establishment parties has not always functioned hermetically, as illustrated by the temporary 2021 collaboration between USR-PLUS and AUR to submit a motion of no confidence against a PNL-led government, it nonetheless remains a structuring feature of coalition formation and elite political behavior. However, this exclusion pattern also appeared to contribute to diversifying and consolidating the support base of radical right populists. AUR almost doubled its vote share, from 9.08% in 2020 to 18.01% in 2024. Two new parties, both led by former AUR members, also managed to pass the 5% threshold and to win seats in the Parliament: SOS România, with 7.36% of the votes, and the Party of Young People (POT) with 6.46% of the vote. Together, the three parties have grown from 9.08% of the vote in 2020 to 31.83% of the vote in 2024. The distribution of the votes for the three populist parties by municipality (see Figure b) shows that they have support throughout the country, with the exception of the two counties where the Hungarian population represents a majority (Covasna and Harghita) and, in the case of POT, of two more counties in which the party did not have time to find candidates (Galați and Ialomița).

Data source: Romanian Permanent Electoral Authority.

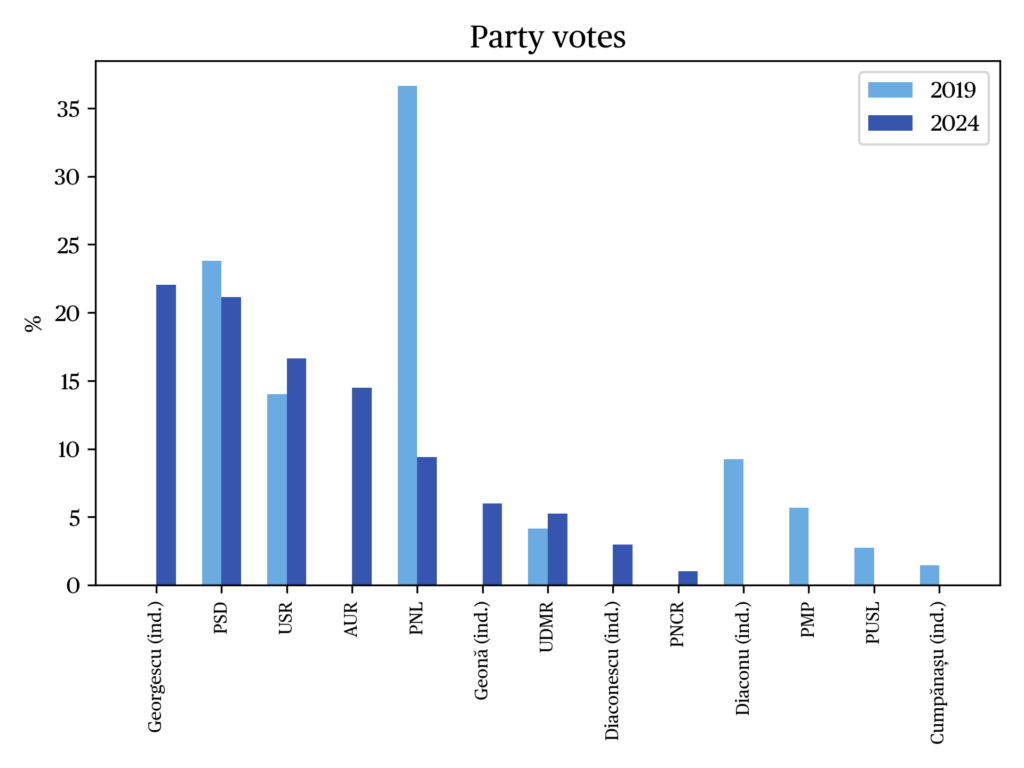

The 2024 presidential elections emerged as the central event of Romania’s mega-electoral year. This reflects the enduring significance attributed to executive leadership within Romanian public opinion, with almost eight out of ten Romanians (79%) believing that the country would benefit from a strong leader unconstrained by Parliament and elections according to the 2018 World Value Survey (Comșa, 2020) 1 . Fourteen candidates entered the race, of whom ten were supported by political parties and four ran as independents, in what was initially expected to be a relatively predictable contest (for a detailed overview, see Stoica, 2025). Following the disqualification of Diana Șoșoacă by the Romanian Constitutional Court (CCR), only four candidates were consistently viewed as serious contenders for advancing to the second round: Marcel Ciolacu (PSD), Nicolae Ciucă (PNL), George Simion (AUR), and Elena Lasconi (USR). Each of these candidates enjoyed explicit backing from established political parties, signaling the continued centrality of partisan support in presidential politics. However, the presence of Lasconi and Simion, two representatives of challenger platforms institutionalized in 2016 and 2020, respectively, demonstrated the growing competitiveness of non-traditional actors within Romania’s evolving party system.

The PSD had high hopes that 2024 would be the year to break the curse of the presidential elections: although the largest political party in Romania, the PSD has failed to win a presidential contest since 2004, with its candidates losing in the second round to Traian Băsescu in 2004 and 2009 and to Klaus Iohannis in 2014 and 2019. Informal accounts suggest that the PSD sought to engineer a second-round confrontation between its own candidate, Marcel Ciolacu, and AUR candidate George Simion, thus framing the election as a stark choice between a pro-European incumbent prime minister and a euroskeptic populist candidate. This strategy was complicated by the CCR’s October 5 decision to exclude Diana Șoșoacă from the race. While the legal justification was widely viewed as tenuous (see Iancu, 2025), critics interpreted the ruling as an indirect maneuver to facilitate Simion’s progression to the second round, eliminating one of his most vocal critics on the nationalist right.

Unexpectedly, in the final week before the election, Călin Georgescu, an independent candidate, emerged as a serious contender, driven by a highly effective campaign on TikTok. Although relatively unknown to the general public, Călin Georgescu was far from a political outsider. Originating from a privileged milieu that benefited from study visits abroad during the late communist period, Georgescu had long belonged to the upper echelons of Romania’s administrative and political structures. Since the early 1990s, he has held senior positions across various ministries, particularly during the late 1990s and early 2000s, building a profile that combined administrative and policy expertise. More recently, in 2021, Georgescu was nominated by AUR as their candidate for prime minister during consultations with President Klaus Iohannis, an episode that further confirmed his proximity to political power and alignment with certain segments of the far right.

Despite his limited name recognition in public debates prior to the first round of the presidential elections, Călin Georgescu emerged as a hybrid political figure: a technocrat and long-time political insider who strategically adopted the rhetorical posture of an independent outsider. His unexpected electoral surge was facilitated by a discursive amalgam of old and new themes, combining nostalgic appeals with contemporary anxieties. His platform was structured around three guiding principles—“Food, Water, Energy”—which, in his own terms, reflect “Christianity applied to the real economy,” and are framed as a triad embodying harmony between God, Man, and Nature.

This ideological framing was underpinned by a pervasive discourse of inclusiveness evoking an organic, traditional community capable of resisting modern-day disintegration, which crossed religious and socio-economic lines, e. Central to his platform was a call for national sovereignty in decision-making, paired with an endorsement of distributism: a socio-economic model that he sees as privileging local production, participatory democracy, and a vision of freedom rooted in brotherhood and solidarity. This model, while couched in spiritual and nationalist language, was also presented as universally applicable, positioning Romania not merely as a beneficiary but as a global source of moral and political inspiration.

Georgescu’s rhetoric frequently adopted a quasi-messianic tone, aligning his persona with a lineage of Romanian heroes and historical figures engaged in struggles against foreign domination and internal moral decay. This discourse resonated with elements of protochronism, a nationalist historiographic tradition that claims Romania as the cradle of global civilization and spiritual renewal (Verdery, 1991). At the same time, Georgescu’s public statements often combined esoteric references, to spiritual energies and metaphysical “balance,” with ambiguous, loosely evidenced propositions, inviting broad interpretation and allowing diverse audiences to project their expectations onto his message. This hybrid and often cryptic discourse gained virality within Romania’s fragile media ecosystem, where traditional journalism has been weakened and social media platforms, especially TikTok, have become dominant sources of political information, particularly among younger demographics. Data from 2024 suggests that Romanians spend approximately 32 hours per month on TikTok, compared to only 13 hours on Facebook, underscoring the platform’s capacity to amplify non-mainstream voices and facilitate the rapid dissemination of simplified, emotionally charged political content (Dincă, 2024). Romania is also the EU country with the highest TikTok penetration as of 2024 (Statista, 2024).

The first-round results defied all initial expectations, throwing the presumed stability into disarray. Georgescu came in first with 22.94% of the vote, followed by Elena Lasconi with 19.18%. The anticipated frontrunners, Marcel Ciolacu and George Simion, finished third (19.15%) and fourth (13.86%), respectively. Four days later, on November 28, the Supreme Council for National Defense (CSAT) announced that Romanian intelligence services had uncovered evidence of foreign electoral interference, prompting the CCR to order an unprecedented nationwide recount. However, logistical and procedural shortcomings marred the process: the Central Electoral Bureau (BEC) conducted only a partial recount, excluding approximately 600,000 votes cast abroad, and independent election observers were not permitted to monitor the process. Despite this, on December 3, the CCR abruptly validated the contested first-round results. In a dramatic reversal, on December 6, as the diaspora vote for the second round was already underway, the CCR intervened again, annulling the entire presidential election on the grounds that recently declassified intelligence confirmed foreign support for Călin Georgescu’s candidacy, thereby creating an unbalanced and unfair electoral competition. This decision sparked widespread criticism from civil society, the media, and the electorate. Observers pointed out a lack of transparency, insufficient evidence, and weak legal reasoning (the CCR ruling was only four pages long) behind the annulment of the most consequential electoral process in the country.

The government rescheduled the presidential elections for May 4–18, 2025, ostensibly to allow time for candidates to prepare new campaigns and for the public to process the extraordinary political developments of late 2024. However, the institutional credibility of Romania’s electoral and constitutional oversight bodies emerged significantly weakened, raising profound concerns about democratic stability, the rule of law, and electoral integrity in the wake of unprecedented judicial and intelligence agency interventions.

Final remarks

The 2024 electoral year marks one of the most disruptive episodes in Romania’s post-communist political history. Characterized by the emergence of unpredictable candidates, escalating legal contestations, and the increasing politicization of foreign policy, these elections exemplify what V. O. Key famously described as critical elections, those junctures at which established party structures stumble, new political alignments emerge, and the underlying rules of democracy are questioned.

The growing divide between traditional political actors and a diverse array of challengers, including traditional national-populists and ideologically hybrid candidates, was far more than rhetorical. It resulted in a profound reconfiguration of Romania’s political arena, driven in part by a mobilized and increasingly decisive diaspora electorate. Once considered peripheral, this non-resident voting bloc has become a strategic political constituency capable of decisively influencing outcomes. Electoral data from the presidential and parliamentary contests underscore a significant shift in diaspora preferences. In 2019, Klaus Iohannis secured an overwhelming 94% of the diaspora vote in the second round, reflecting support for a centrist, pro-European vision. By 2024, this consensus had fragmented. Independent candidate Călin Georgescu led in the diaspora vote in the first round with 43.16%, followed by Elena Lasconi (26.95%), another figure standing outside the mainstream political establishment. Established party leaders such as Marcel Ciolacu (2.86%) and Nicolae Ciucă (4.63%) fared poorly. In the 2025 presidential rerun, George Simion dominated the diaspora vote again with 60.8% in the first round and 55.86% in the second, despite losing the overall election to Nicușor Dan.

The 2024 parliamentary elections also reflected this trend. AUR more than tripled its diaspora support compared to 2020, while new platforms such as POT and SOS România collectively secured over 30% of the diaspora vote. In contrast, traditional parties such as the PSD and PNL were relegated to marginal roles, with the latter disqualified from the diaspora ballot entirely due to non-compliance with gender parity requirements. This shift not only highlights the diaspora’s evolving political preferences but also signals their increasing autonomy from domestic party structures.

A defining moment of this electoral year was the annulment of the 2024 presidential election following the first round, a decision that sent shockwaves through Romania’s institutional framework. The ensuing legal disputes extended beyond domestic jurisdictions, engaging European legal bodies and underscoring a broader process of judicializing politics. The exclusion of high-polling candidates such as Călin Georgescu and Diana Șoșoacă from the 2025 re-run on national security grounds further deepened tensions and eroded trust in institutional neutrality.

This period also highlighted the transnational and digital nature of contemporary Romanian politics. The electoral campaign was increasingly shaped by a globalized online ecosystem, where narratives of technocratic overreach, elite conspiracies, and national sovereignty gained traction. Public debates were no longer confined to domestic platforms: foreign influencers, including Elon Musk, publicly engaged with Romanian electoral controversies, while TikTok and other digital platforms amplified these discourses well beyond national borders. Journalistic investigations also revealed extensive digital mobilization strategies dating back to the post-2016 period, blurring the lines between organic political participation and orchestrated influence campaigns.

Despite the eventual victory of Nicușor Dan, a centrist and pro-European candidate, in the 2025 runoff, the legitimacy of the process remains contested. The campaign’s turbulence and the unresolved institutional disputes left deep divisions. Dan’s win, while symbolically important for the political center, did not arrest the populist momentum. Simion’s strong national support and continued diaspora dominance affirm that the structural conditions sustaining populist and anti-establishment sentiment remain firmly in place.

Romania’s democracy has withstood this volatile moment, but it has emerged from it more fragmented, more contested, and more dependent on transnational constituencies than ever before. These elections were not simply about the alternation of political power, but rather about the foundations of democratic legitimacy, the evolving geography of political participation, and the fragility of institutional trust.

The data

Parliamentary election

Presidential election: first round

References

Biroul Electoral Central (2024, 9 June). Comunicat BEC privind lista partidelor politice, organizațiilor cetățenilor aparținând minorităților nationale…

Borțun, V. (2025, 16 May). Romania Is About to Experience Disaster. New York Times.

Casal Bértoa, F., & Enyedi, Z. (2021). Party System Closure: Party Alliances, Government Alternatives, and Democracy in Europe. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Comșa, M. (2020). Raportarea la politică și sistemele de guvernare. In B. Voicu, H. Rusu & C. Tufiș (Eds.), Atlasul valorilor sociale: România la 100 de ani (pp. 71–80). Cluj Napoca: Presa Universitară Clujeană.

De Vries, C., & Hobolt, S. (2020). Political Entrepreneurs: The Rise of Challenger Parties in Europe. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

Dincă, T. (2024). TikTok a câștigat bătălia atenției în România. 2024 – primul an când TikTok va depăși Facebook în România. Profit.ro.

Dumitrescu, V. (2024). Cronica unei morți neanunțate. Decăderea USR de la partidul star anti-sistem, la prăpastia irelevanței electorale. Cronica unei morți neanunțate. Panorama.

Grama, A. (2025). The revenge of civil society. Journal of Contemporary Central and Eastern Europe, 33(1): 211–19.

Iancu, B. (2025). Militant Democracy and Rule of Law in Three Paradoxes: The Annulment of the Romanian Presidential Elections. Hague Journal on the Rule of Law.

Ioana, C. (2024). Este AUR de capul lui la europarlamentare? Cum i se aude mesajul în corul partidelor de extremă dreapta din Europa. Panorama.

Key, V. O. (1955). A theory of critical elections. The Journal of Politics, 17(1): 3–18.

Mudde, C. (2007). Populist Radical Right Parties in Europe. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Pârvu, L. (2024). Marile mize ale comasării alegerilor: cum vor PSD și PNL să-și conserve puterea și să taie din elanul AUR și al Dianei Șoșoacă / Toate calculele făcute în culisele partidelor. Hotnews.

Soare, S. (2024). Charting Populist Pathways: Romanian Populism’s Journey to the European Parliament. In G. Ivaldi & E. Zankina (Eds.), 2024 EP Elections under the Shadow of Rising Populism, European Center for Populism Studies.

Stoica, C. (2025). Turul doi care n-a fost: Autopsia sumară a unui moment electoral (sperăm) unic. București: Humanitas.

Tufiș, C. (2024). Les élections parlementaires européennes de 2024 en Roumanie: Une élection dominée par les enjeux locaux. Politique européenne, 86: 230–38.

Verdery, K. (1991). National Ideology Under Socialism: Identity and Cultural Politics in Ceausescu’s Romania. Berkeley: University of California Press.

Notes

- Usually, this question is part of a set of four items measuring attitudes towards democracy and its alternatives. Romanians have an ambivalent position on these issues: on the one hand, 90% of the respondents consider having a democratic political system is good for the country, while on the other, 79% support the idea of a strong leader, 84% support the idea of a technocratic government, and 34% support the idea of a military regime.

citer l'article

Sorina Cristina Soare, Claudiu D. Tufiș, Parliamentary and presidential elections in Romania, November-December 2024, Sep 2025,

à lire dans cette issue

voir toute la revue