Parliamentary election in Estonia, 5 March 2023

Piret Ehin

Professor of Comparative Politics at the University of TartuIssue

Issue #4Auteurs

Piret Ehin

Issue 4, January 2024

Elections in Europe: 2023

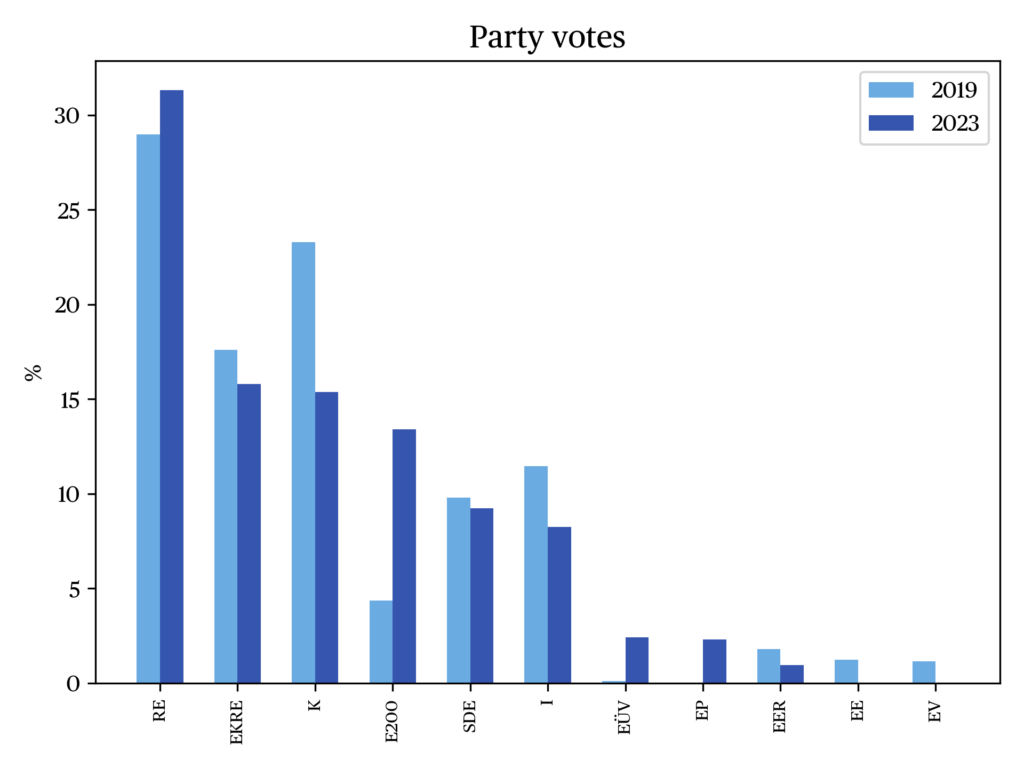

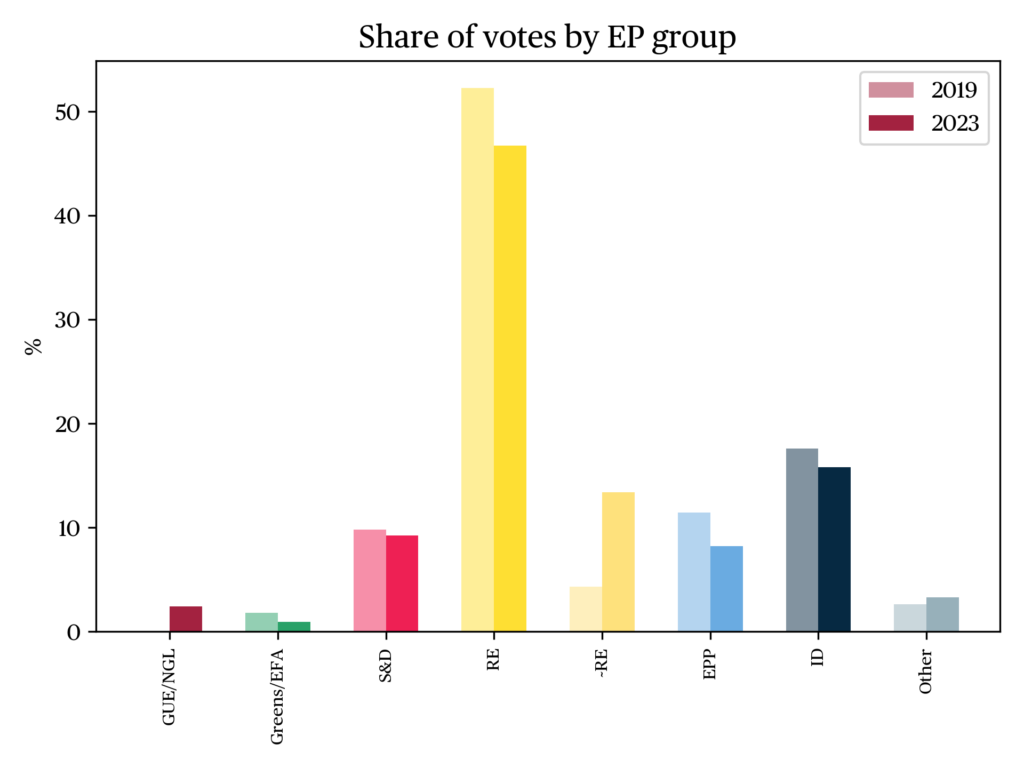

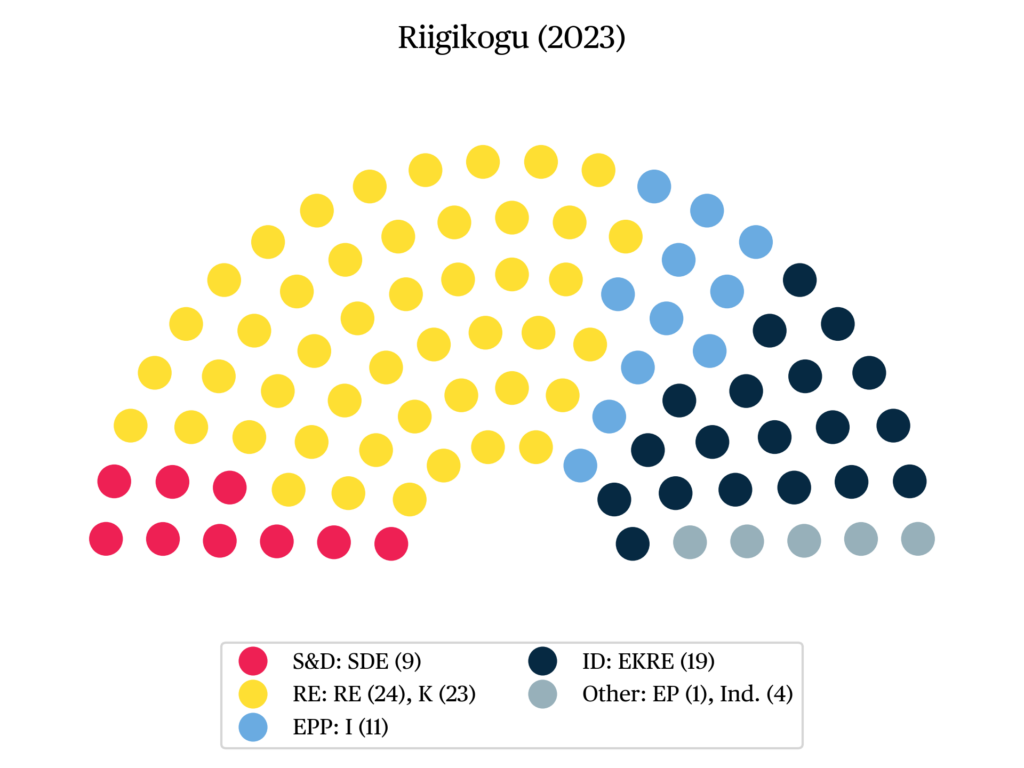

Held in the context of Russia’s war of aggression in Ukraine, the 2023 general election in Estonia saw a landslide victory of the liberal, centre-right Reform Party led by incumbent Prime Minister Kaja Kallas. Turnout, at 63.53%, was almost the same as in the previous general election held in March 2019. Six parties gained representation in the 101-member Riigikogu, Estonia’s unicameral parliament. The liberal, pro-market and firmly pro-Western Reform Party took 31.2% of the vote and 37 seats (up 3 from the previous election). The Conservative People’s Party of Estonia (EKRE), which is classified as a populist radical right party, placed second with 16.1% of the vote and 17 seats (two less than in 2019). The Centre Party, which is popular among Russian-speaking voters, won 15.3% of the vote and 16 seats (a loss of 10 from 2019). Estonia 200, a liberal party founded in 2018, entered the parliament for the first time, winning 13.3% of votes and 14 seats. Social Democrats took 9.3% of the vote and 9 seats (one less than in 2019), while the conservative Pro Patria won 8.2% of the vote and 8 mandates (down from 12 in the previous election).

Electoral system and voting arrangements

The Riigikogu is elected for a four-year term through a proportional open-list system from 12 multi-mandate districts. The number of seats per electoral district varies from 5 to 16. Voters cast a vote for a candidate from the district party list or support an independent candidate. The electoral threshold is 5%. There is a three-tier system for distributing mandates (personal, district, and compensation mandates).

Estonia offers a number of special voting arrangements, including early voting (during the week leading up to election day), postal voting, voting at diplomatic representations, mobile ballot boxes, and remote internet voting. Notably, Estonia remains the only country in the world to offer all voters the option of casting a ballot online (from any Internet-connected computer from any location in the world). Internet voting took place during the week leading up to election day (in previous elections, it was possible up to four days in advance). To vote online, voters download a voting application, launch it on their computers, authenticate themselves using the Estonian ID-card or a mobile-ID, view the list of candidates running in their district, make their choice, and confirm their vote with a digital signature. Remote internet voting, which was introduced in 2005, is highly popular and widely trusted (see Ehin, Solvak, Willemson and Vinkel 2022). The March 2023 Riigikogu election was the first election where more than half of the votes (50.97%) were cast electronically over the Internet.

Context

The election took place in the context of Russia’s war of aggression in Ukraine. Having restored its independence in 1991 after a half-century of Soviet occupation, Estonia has been a member of the EU and NATO since 2004. The small country shares a 340-kilometer border with the Russian Federation. Under the government led by the Reform Party, Estonia has been a staunch supporter of Kyiv, providing military, economic and humanitarian assistance as well as political support: relative to GDP, Estonia has provided more government support to Ukraine than any other nation (Kiel Institute for the World Economy 2023). During the first year of the full-scale war, Prime Minister Kaja Kallas (Reform Party) emerged as one of Europe’s most outspoken supporters of Ukraine, with the Prime Minister’s and her party’s strong stance leading to a significant increase in public support for the Reform Party (by about 10 percentage points between February and May 2022).

During the first year of the full-scale war, nearly 125,000 Ukrainian refugees entered Estonia (which has a population of 1.3 million), of which about a half were in transit and 70,000 stayed in the country (Tammark 2023). While ethnic Estonians, who make up 69% of the country’s population, have been overwhelmingly supportive of Ukraine and in favor of admitting Ukrainian refugees, the views of ethnic Russians, who constitute a quarter of the population, have been mixed and often influenced by narratives promoted by pro-Kremlin actors. Thus, the war has intensified the ethnic cleavage in Estonian politics. Tensions were on display at Estonia Easternmost city, Narva, in August 2022, when the government removed a Soviet-era war monument (a Red Army tank on a pedestal) despite strong opposition among the city’s Russian-speaking residents.

The election took place in the context of a cost-of-living crisis which was, at least partly, triggered by Russia’s invasion of Ukraine. In the second half of 2022, Estonians experienced some of the highest inflation rates in the EU, which exceeded 20% for several months. Energy and food prices rose rapidly. In this context, opposition parties, especially the radical right EKRE, sought to capitalize on a growing dissatisfaction with the increased cost of living (Euractiv 2023).

Contenders and campaigns

Nine political parties and ten independent candidates registered to take part in the 2023 parliamentary election. Three parties – Reform, Pro Patria, and the Social Democrats – were part of the governing coalition led by Prime Minister Kaja Kallas. The Centre Party, led by Jüri Ratas, and the Conservative People’s Party (EKRE), led by Martin Helme, were the main opposition forces. A number of extra-parliamentary parties contested the election, including the Greens, founded in 2006; the Right-wingers, formed in 2022; the liberal Estonia 200, formed in 2018; and the United Left Party, a marginal left-wing and pro-Russian minority party whose origins can be traced back to the Communist Party of Estonia. In the 2023 election, the United Left Party had formed an informal alliance with Together, a pro-Kremlin social movement that emerged in spring 2022 in the wake of Russian invasion of Ukraine.

The issues discussed during the campaign period were the cost-of-living crisis, national security and defense, the war in Ukraine and its multiple repercussions (including the refugee crisis), as well as tax reforms and the proposed transition to Estonian-language education in Russian-language kindergartens and schools.

The ruling Reform Party’s main rival in this election was EKRE, a party that had consistently ranked second in the polls. Public debates between Prime Minister Kaja Kallas (45) and EKRE’s leader Martin Helme (46) were often heated. While the Reform Party stands for liberal values, fiscal conservatism, pro-market policies, and firmly anti-Kremlin and pro-Western policies, EKRE is widely described at populist, provocative, nationalist, nativist, socially conservative, traditionalist, xenophobic and Euroskeptic. While the Reform Party is viewed as representing well-off, educated, urban and liberal elites, EKRE is preferred by the less educated, rural voters, and men. Formed in 2012, EKRE had first gained parliamentary representation in 2015 in the context of the European migration crisis. In the 2023 campaigns, EKRE politicians opposed the pro-Ukrainian agenda of Kaja Kallas and her party, and blamed the government for the cost-of-living crisis. Members of EKRE played up the dangers posed by the influx of war refugees, and emphasized the cost of Estonia’s assistance to Ukraine.

The biggest stir during the campaign period was caused by an article published by Politico on February 18, about three weeks before the election. The article claimed that Russian oligarch and head of the Wagner private military company, Yevgeny Prigozhin had tried to influence the 2019 elections in Estonia by conducting a disinformation operation through EKRE media and communication channels. EKRE rejected the claims and Estonian counter-intelligence agencies did not confirm any links between Prigozhin and EKRE. However, the widely discussed scandal may have diminished electoral support for the party.

Analysis of the results

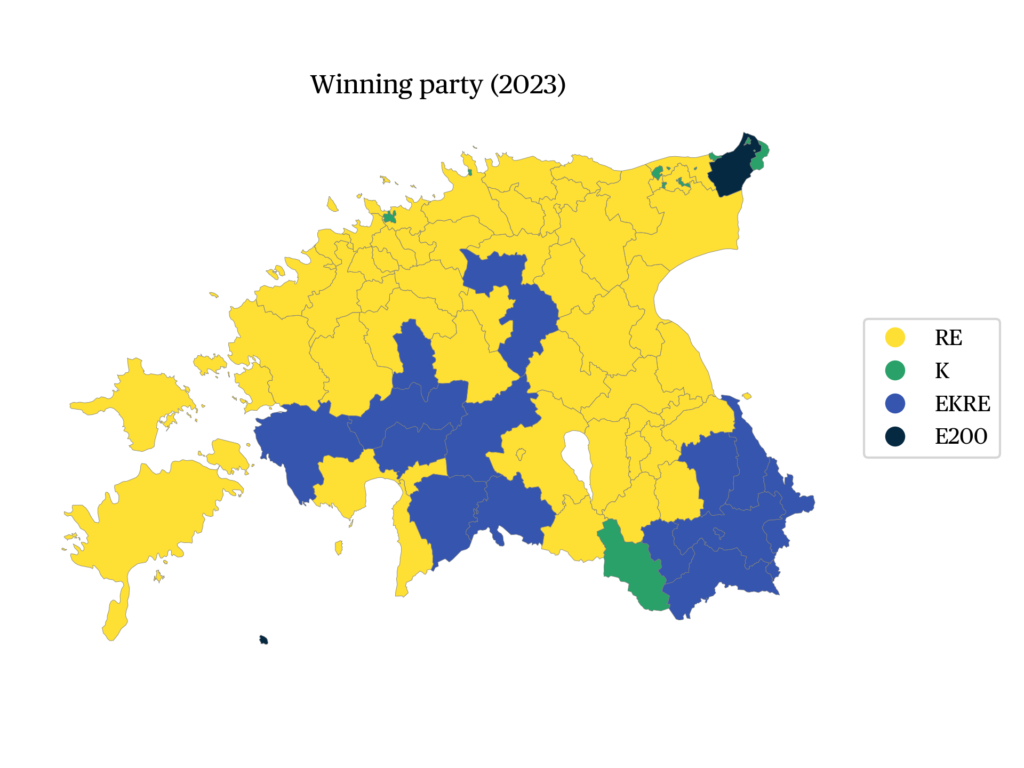

Overall, 613,801 voters cast a vote in the 2023 general election – almost 50,000 more voters than four years ago. Although voter numbers set a new record, the official turnout rate (63.53%) was effectively the same as in March 2019. This is due to a change in turnout methodology (over 80,000 Estonian citizens living abroad were added to the register). Turnout was highest in Harju and Rapla counties (70.1%) and lowest in the predominantly Russian-speaking Ida-Viru county in the North-East (46.6%).

The Reform Party’s vote share exceeded expectations. With 31.2% of the vote (almost twice as much as the second-placed EKRE) and 37 seats, the party got a strong mandate to continue to govern. Prime Minister Kaja Kallas became the biggest vote-getter in the history of Estonian elections (31, 816 votes). Her principled stance on Russia and Ukraine and the party’s effective campaigning around national security clearly contributed to this electoral feat.

EKRE’s performance fell short of expectations. With 16.1% of the vote, the party lost 2 seats. The party’s strategy of focusing on economic woes and the cost-of-living crisis, while taking a relatively soft stance on Russia and opposing the admission of Ukrainian refugees appears to have been a questionable approach in the context of very strong public support for Ukraine.

The Centre Party was the biggest loser of these elections, giving up 10 seats in parliament. The party had been in crisis for several years. Marred by cooperation with the far-right EKRE in a governing coalition led by Jüri Ratas in 2019-2021 as well as by corruption scandals that led to the resignation of the Ratas government in 2021, the party struggled to position itself vis-à-vis the war in Ukraine. Trying to appeal to both ethnic Estonians and Russian-speaking voters, the party could not satisfy either, coming off as either too soft or too harsh on Russia.

With 14 seats, Estonia 200 performed very well, gaining parliamentary representation for the first time. The party succeeded in positioning itself as a convincing alternative to Reform, appealing to liberal-minded, educated and young voters.

Pro Patria’s meager performance (8 seats) seems to reflect its inability to clearly distinguish itself from competitors – recently, the party has often been referred to as EKRE-light. The Social Democrats ran a campaign that tried to emphasize both security issues and economic concerns but the party’s main election slogan “Coping is national security” was not particularly compelling.

In terms of regional results, election outcomes in the predominantly Russian-speaking Ida-Viru country were widely referred to as a ‘a shock’ and ‘a wake-up call.’ The biggest vote-getters were Mihhail Stalnuhhin, an independent candidate who, in the context of the removal of the tank-monument in Narva, had called the Estonian government ’fascist’, and Aivo Peterson, a candidate of the United Left Party who prior to the election had toured occupied territories of Ukraine, making pro-Kremlin statements. These results can be seen as a testament to dissatisfaction with the national government in the region as well as the appeal of pro-Kremlin narratives among segments of the Russian-speaking population in Estonia.

Government formation

Before the election, Kaja Kallas had ruled out a government with EKRE. The remaining four parliamentary parties – Centre, Pro Patria, Social Democrats and Estonia 200 – remained potential coalition partners, although Reform’s relations with the Centre Party had been strained for several years. A new liberal government, consisting of Reform, Estonia 200, and the Social Democrats, with Kaja Kallas continuing as the Prime Minister, was sworn in on 17 April. The three parties’ policy agendas overlap in many respects and the new coalition has a comfortable majority of 60 seats in the 101-member parliament.

The Data

References

Ehin, P., Solvak, M.,Willemson, J., & Vinkel, P. (2022). Internet voting in Estonia 2005–2019: Evidence from eleven elections. Government Information Quarterly, 39:4.

Euractiv.com with Reuters (2023, 2 March). Estonia faces election amid cost of living crisis. Euractiv.com

Kiel Institute for the World Economy (2023). Ukraine Support Tracker: A Database of Military, Financial and Humanitarian Aid to Ukraine. Online.

Tammark, M. A. (2023, 1 March). Ukrainian refugees in Estonia. Estonian World Review.

citer l'article

Piret Ehin, Parliamentary election in Estonia, 5 March 2023, Nov 2023,

à lire dans cette issue

voir toute la revue