Parliamentary election in Germany, 26 September 2021

Andrea Römmele

Professor of Communication at the Hertie School of GovernanceIssue

Issue #2Auteurs

Andrea Römmele

21x29,7cm - 167 pages Issue 2, March 2021 24,00€

Elections in Europe : June 2021 – November 2021

Initial situation

The 2021 super-election year was special with regards to several aspects. For the first time in the history of the Federal Republic of Germany, the incumbent did not stand for re-election, i.e. there was no candidate who entered the election campaign with a chancellor’s bonus. For the first time, there were also three top candidates instead of the usual two; due to the persistent good poll ratings, the German Green Party Bündnis 90/Die Grünen also decided to enter the race with a female top candidate. Three state elections were also held in the 2021 super election year, which were also seen as a mood test for the 2021 federal elections: Baden-Württemberg and Rhineland-Palatinate in March 2021 and Saxony-Anhalt in June.

The following article is divided into three parts. First, the federal elections will be discussed as a “turning point in Germany’s electoral history” (Schmitt-Beck 2021: 10). What changes in citizens’ voting behavior can be identified? We then take a look at the election campaign strategies and dramaturgies of the individual parties. Lastly, the analysis concludes with possible coalition options. The article provides an overview of the chronology of the most important events and structures them on the basis of the academic literature and the author’s assessments.

Fluctuating approval ratings — changes in electoral behavior in the run-up to the election

In electoral sociology, three factors are assumed to determine voting preference: party loyalty (long-term factor), campaign issues, and candidates (both short-term factors) (Schmitt-Beck 2021: 10). Party identification develops during adolescence and early adulthood and is strongly influenced by education, parental home and peer groups. This party attachment is long-term and hardly changes over the course of a lifetime. The bond may weaken, but rarely turns to the other extreme. Short-term factors, on the other hand, are the elements that change from election to election, namely campaign issues and candidates (Schmitt-Beck 2021: 11). In practice, however, this looks different in many cases — we have been observing a significant decline in party loyalty and a concomitant increase in the volatility of voting behavior for a long time (cf. Arzheimer 2017). In addition, there is a creeping but continuous decline of the mainstream parties and an increasing fragmentation of the party system. This is not a uniquely German phenomenon, but a development that we can observe throughout Europe (cf. Ford & Jennings 2020).

Even though these developments are not new, they correlate with two other important phenomena in Germany. First, the distinctive strength of the Green Party, which even sent a top candidate into the run-up to the Bundestag elections and was considered the most dangerous rival to the Christian Democrats CDU/CSU for an extended period of time (cf. Lees 2021). Second, the nationalist Alternative for Germany (AfD) has established itself in federal politics as a party that no other party would consider as a possible coalition partner. This significantly shifts the overall dynamics of the political system toward a six-party system, in which two parties will rarely be sufficient to form a governing coalition. Thus, finding coalitions is likely to become much more difficult in the future (see Dostal 2021).

With the decline in party ties as a long-term factor, the short-term factors in an election campaign, namely candidates and campaign issues, have become all the more important. Since these usually differ from election to election, their communication, i.e. a party’s respective campaign, also becomes more important. Therefore, as we have witnessed repeatedly in the recent past: campaigns do matter! We saw this in the 2016 U.S. election campaign, in the 2017 Brexit referendum, and in the 2021 German election campaign (see, for example, Römmele & Gibson 2020). This is also reflected in the increased role of social media as an important campaign element. This medium is used by both parties and individual candidates to communicate political content and establish personal proximity relationships (cf. Haßler, Kümpel & Keller 2021).

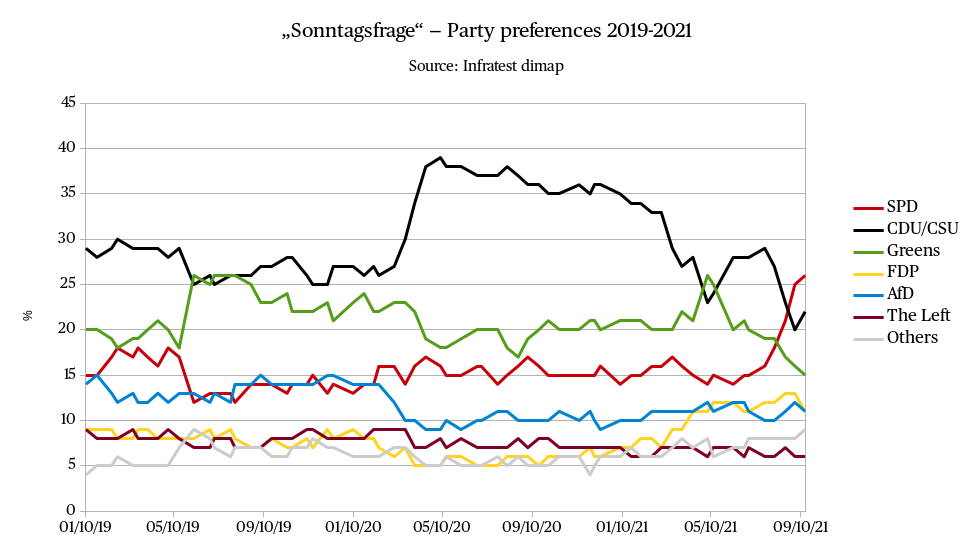

It has been often emphasized that voting behavior has changed significantly due to greater volatility in elections and the perceived complexity of political issues and increasing uncertainties (cf. Schmitt-Beck 2021). This long-term development poses a particular challenge to parties and candidates in election campaigns. The graph below showing a comparison of the Sunday polls from January 2019 to September 2021 illustrates just how unstable voter’s opinions have been. Despite supposedly constant support for the individual parties, unusually rapid jumps within the poll results are apparent.

In this context, we saw the CDU/CSU on a constant course below 30 percent in 2019 — the signs of wear and tear after 15 years in government, a weak party leader (Annegret Kramp-Karrenbauer) who could not unite the party behind her and a party that was facing massive competition from the AfD, especially in eastern Germany, are visible (cf. Pesthy, Mader & Schoen 2021). Similar swings, albeit in a positive direction, could be seen among the Greens in 2019. The two party leaders, Annalena Baerbock and Robert Habeck, succeeded in uniting the party and putting it back on course for the government. The increasingly pressing climate policy challenges put the Greens’ core issue at the top of the political agenda — tailwind in polling heaven. A party that garnered just 8.6% of the vote in the 2017 federal election is starting to dream of the chancellorship (see also Lees 2021). In contrast, there were fewer swings in 2019 for the other parties. The Social Democrats (SPD) were trailing behind, sometimes slightly above the 15% mark, sometimes slightly below. The left-wing party leaders, Saskia Esken and Norbert Walter-Borjans, managed to bring the party into calmer waters, but this did not yield an increase in the poll ratings. The FDP and the Left Party were also relatively constant at around 10% and the AfD was holding steady between 14-15% in 2019.

The pandemic changed the picture quite radically: under Angela Merkel’s crisis-tested leadership in the first and second Covid waves (until mid-March 2021), the CDU/CSU experienced a poll high of nearly 40%. Crises are the watchword of the executive, but the executive must also deliver. And that is what Angela Merkel and her team were doing in the first as well as second pandemic waves. People trusted her, she struck the right note as a natural scientist and enjoyed great popularity in her 16th year as chancellor. The Greens fell back again and settled around 20%. Almost silently, the SPD elected its candidate for chancellor, Olaf Scholz, vice chancellor and finance minister of the grand coalition, in August 2020, the first pandemic summer. This was hardly newsworthy; some observers even feared that the SPD could fall below the 10% mark.

While everything was running smoothly (unusually for the SPD), however, rifts were breaking open in the CDU/CSU. With the resignation of party chairwoman Annegret Kramp-Karrenbauer, the battle for the party leadership and thus also for the chancellor candidacy in the CDU/CSU had begun. Three candidates stood for election. In a runoff election, Armin Laschet, then Minister President of North Rhine-Westphalia, won against Friedrich Merz. While Laschet, in winning the party chairmanship, assumed that he had first dibs on the chancellor’s candidacy, in Munich, CSU Chairman and Bavarian Prime Minister Markus Söder prepared to take over. He was a good and strict Covid crisis manager, always campaigned for sharp and consistent measures together with the chancellor and thus also earned the position of primus-inter-pares in the ministerial presidency. Söder suddenly enjoyed a high level of popularity, far beyond Bavaria, and challenged Armin Laschet. The tug-of-war over the chancellor candidacy in the CDU/CSU dragged on for 3-4 weeks in the spring of 2022 and brought the worst conceivable start for the CDU/CSU in the super election year. Laschet was elected by the party executive in a brute cloak-and-dagger action, against Söder’s high approval rating in the party. Söder thus lost out as the “candidate of the heart” and made Armin Laschet feel this during the election campaign.

Campaign strategy

But let’s look at the parties’ election campaign strategies. The SPD proclaimed its candidate for chancellor, Olaf Scholz, early on and rallied the entire party behind him. No divisions, no discord. The ones responsible, Lars Klingbeil and Wolfgang Schmidt, relied on the vice chancellor’s experience and government expertise and skillfully presented Olaf Scholz as Merkel’s natural successor. He was the real incumbent in this Bundestag election campaign. Scholz radiated confidence, took part in the crisis management in the first and second Covid waves, and was thus able to score, with his past experience and successes, as a quasi-incumbent. For the CDU this made him difficult to attack (see Schmitt-Beck 2021). As for the SPD, this was the strategic masterstroke of their campaign.

The CDU got off to a false start to the election campaign with their personnel quarrels and also relied on the wrong strategy. The CDU election campaign was focused on Armin Laschet as the incumbent, a candidate who has government experience as minister president of Germany’s most populous state. The opponent was to be Annalena Baerbock, the young Green Party chairwoman, who also openly admitted that she lacked precisely this experience but had the fresh new look that was needed. Only in recent months has it become clear that the decisive opponent was not Annalena Baerbock, but Olaf Scholz. And in this duel, Laschet was the challenger, a role that he did not slip into and that did not suit him. This became more than clear, especially in the TV debates. In addition to this strategic misjudgment and misplanning, the chancellor candidate also made a crucial mistake: due to the flood disaster in the Ahr Valley in western Germany (the Ahr Valley is located in Rhineland-Palatinate and North Rhine-Westphalia), Armin Laschet was forced to engage in crisis management in his own “Bundesland”. This was actually an opportunity for the candidate chancellor — as part of the executive, you can always score points in crises (see also Dostal 2021). However, he made a momentous mistake: during a speech by the Federal President in the Ahr Valley, Armin Laschet could be seen in the background joking and laughing with his team. This insensitivity and unprofessionalism stuck with him and, in retrospect, was a turning point in the CDU/CSU election campaign.

The Christian Democrats also lacked support from within their own party. Some state associations would have preferred Markus Söder to be their candidate for chancellor and nearly refused to follow Armin Laschet. The chancellor election machine, which used to function so well, had come to a standstill. Even Angela Merkel’s half-hearted support two weeks before the election date arrived too late.

The Greens also struggled during the election campaign. While Annalena Baerbock’s election as the first female candidate for chancellor was still a magnificent staging of the party and briefly led the Greens at a polling high (see Lees 2021), the chancellor candidate’s own mistakes — unnecessarily embellished resume, plagiarism in a book published during the campaign — quickly brought the Greens back well below the 20% mark in the polls. The female candidate could not get rid of this stigma during her entire election campaign. Although the core issue of the Greens, climate change and environmental protection, was more dominant than ever, it was also overshadowed by the flood disaster in the Ahr Valley and the ongoing Covid crisis (cf. Venghaus, Henseleit & Belka 2022).

To understand the election campaign and the very good result of the Liberal Party (FDP), one has to take a closer look at its role in the last two years. First, the FDP has played a very visible constructive opposition role in the Corona crisis. They have repeatedly raised the issue of civil liberties in times of lockdown and thus also revived the brand essence of the liberal party. In doing so, they were no longer perceived merely as an economically liberal party, but also as a civil rights party. Second, the FDP had already put digitization on the political agenda as a key issue in the 2017 election campaign, and the pandemic made this even more urgent (see Merten 2021).

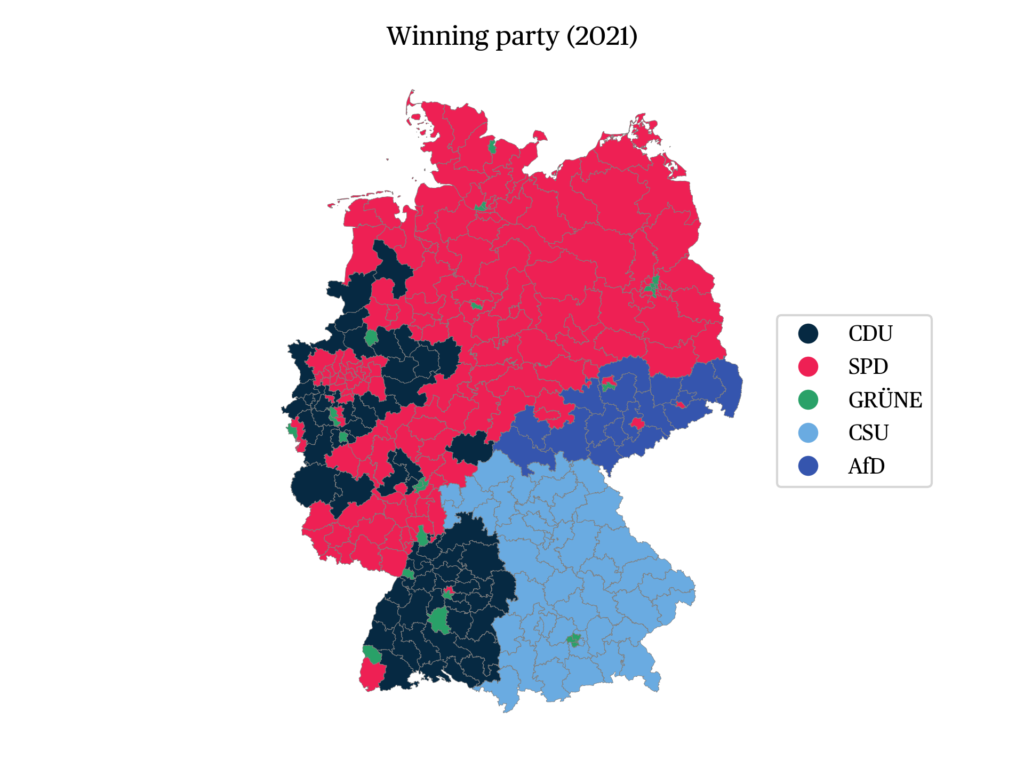

The AfD had several problems in their election campaign: as a party that vehemently opposed the admission of refugees in 2017, it had simply lost their core campaign issue in 2021. Furthermore, there were and still are internal party disputes that hurt the party. Moreover, being the party of anti-vaccinationists did not do themselves any favor during the pandemic either. Nevertheless, they still have their supporters and strength in eastern Germany, where they are a strong regional party (see Pesthy, Mader & Schoen 2021)

Election result

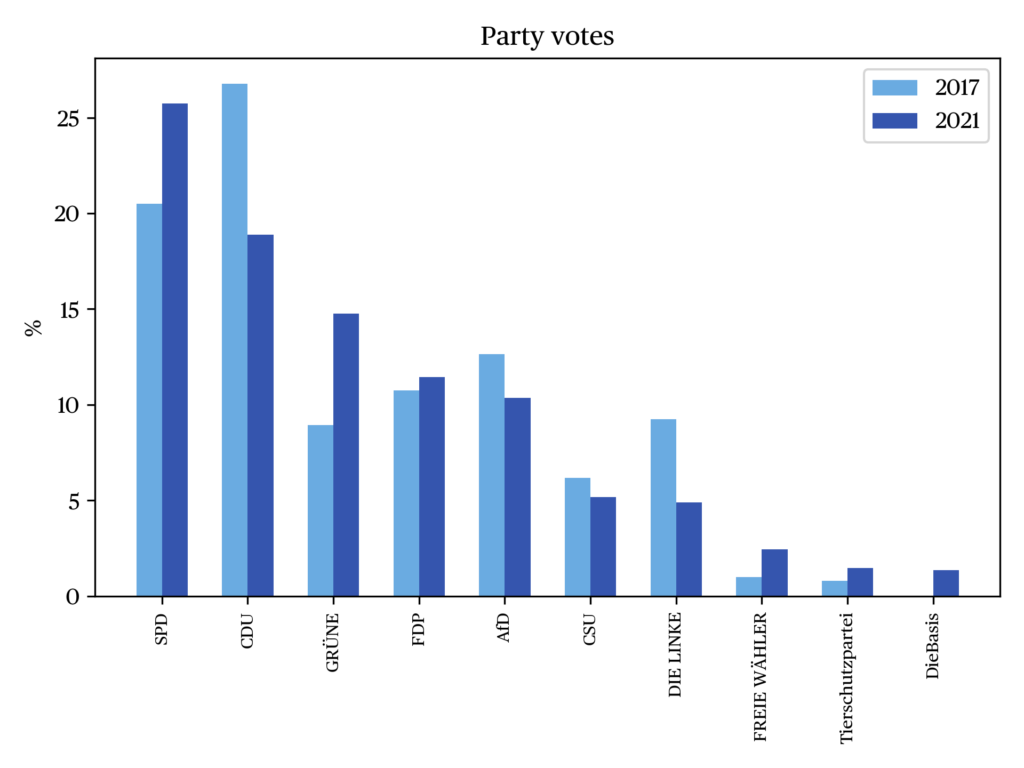

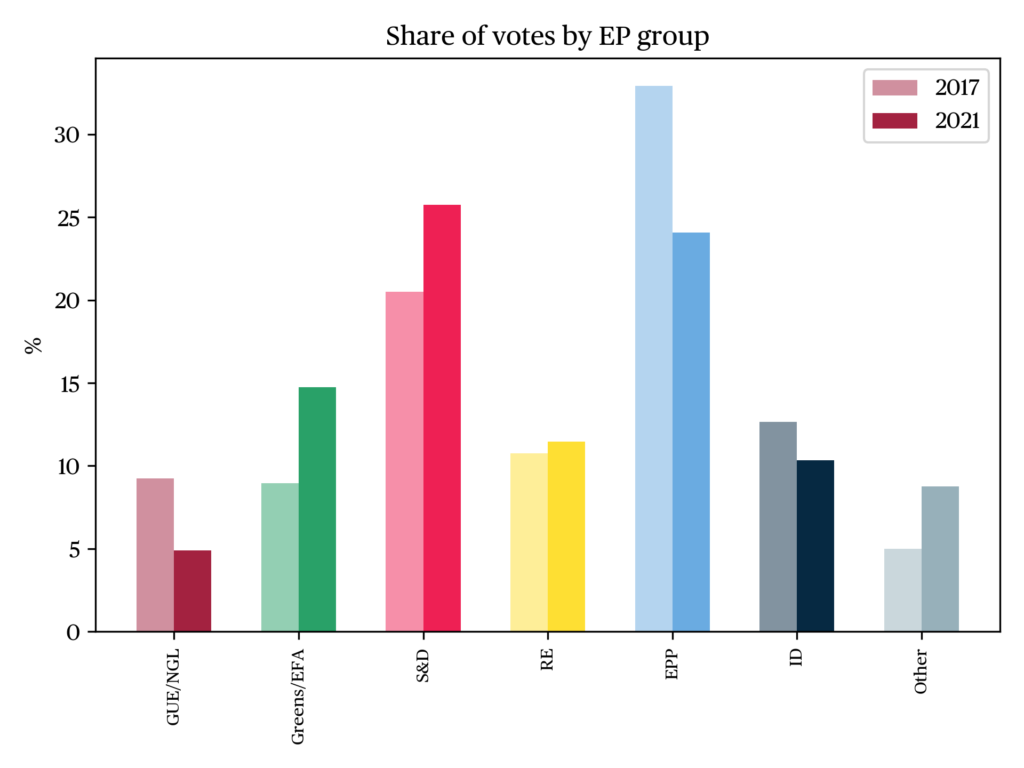

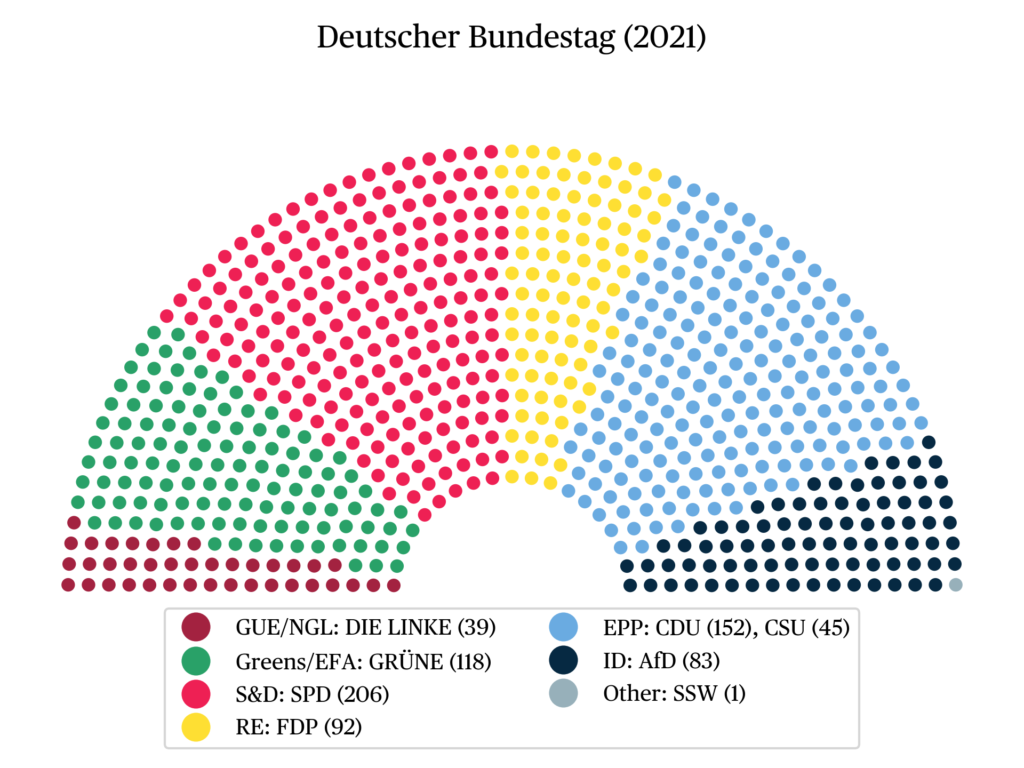

In the weeks leading up to the election, a neck-and-neck race between the SPD and the CDU/CSU emerged – which the SPD won with a 1.6% lead. The CDU/CSU achieved their worst result, falling at 24.1%. The Greens were both pleased and disappointed. Although they gained 5.8 percentage points and ended up in third place with 14.8%, they fell well short of their goal of the “chancellorship”. Once again, the Greens experienced that polls are not votes. The FDP made slight gains, AfD and the Left lost significantly — but without question: the loser of the election night was the Christian Democrats. Several reasons can be cited for this: (1) The top candidate was a burden in the election campaign and was at no time uncontroversial. (2) The Christian Democrats failed to retain the votes that elected Angela Merkel (and not CDU) in 2017. (3) The CDU/CSU realized too late that the SPD’s strategy of taking the incumbency bonus with Olaf Scholz would be most dangerous to the CDU.

The Greens and FDP scored particularly well with first-time voters. In each case, 23% of first-time voters chose either the FDP or the Greens.

Coalition options

With the huge weakening of the mainstream parties SPD and CDU/CSU, it had been clear for some time that, with a certain degree of probability, a three-party alliance would form the next government — the traffic light (SPD, FDP, Greens) was discussed, as was a possible Jamaica coalition. The latter was, after all, already negotiated unsuccessfully in 2017 between the CDU/CSU, FDP and the Greens, however it failed after tough exploratory talks with the FDP. In the weeks before the election, rumors were already circulating in Berlin’s political environment that the FDP and the Greens would meet to discuss who among them would become chancellor. After all, it was clear that there would hardly be a government without these two parties, even if a renewed “Grand Coalition” would have been mathematically possible.

This was exactly what was confirmed in the days after the election: after the historic loss of the CDU/CSU, it quickly became clear that a coalition with the big election loser would not be possible. Moreover, the CDU virtually imploded: the candidate for chancellor, Armin Laschet, resigned from the party chairmanship, the search for a new party leader began, and it soon became evident that the CDU was not fit to govern in this state. Therefore the SPD, FDP and the Greens promptly began exploratory and then coalition negotiations. As early as December 8, 2021, Olaf Scholz was elected as the fourth Social Democratic Chancellor after Willy Brandt, Helmut Schmidt and Gerhard Schröder.

The new coalition now presents itself as a progressive government that wants to launch far-reaching and forward-looking projects and transformations. The tasks are enormous. But because of the greatly altered balance of power between the parties, the government’s work will be characterized by a three-party alliance in which each party wants to set its own priorities. These are in part very different. This complication was already evident during coalition negotiations, in which the FDP in particular, despite being the smallest partner, was able to achieve several concessions. The Greens in particular could possibly have much to lose here.

This analysis of the federal election has also been published in German in the l’IDS-Jahrbuch 2021 of the Leibniz-Institut für Deutsche Sprache.

Literature

Arzheimer, K. (2017). Another Dog That Didn’t Bark? Less Dealignment and More Partisanship in the 2013 Bundestag Election. German Politics 1/2017, pp. 49–64.

Dostal, J. (2021). Germany’s Federal Election of 2021: Multi-Crisis Politics and the Consolidation of the Six-Party System 2021, The Political Quarterly, 92(4), pp. 662-672.

Ford, R. & Jennings, W. (2020). The Changing Cleavage Politics of Western Europe, Annual Review of Political Science 23/2020, pp. 295–314.

Haßler, J., Kümpel, A. & Keller, J. (2021) Instagram and political campaigning in the 2017 German federal election. A quantitative content analysis of German top politicians’ and parliamentary parties’ posts. Information, Communication & Society.

Lees, C. (2021) German federal election: are the Greens on the cusp of government? LSE European Politics and Policy (EUROPP) blog. Blog. Online.

Merten, H. (2021). Wählen in Zeiten der Pandemie. Aus Politik und Zeitgeschichte, 71(47-49), pp. 26–33.

Pesthy, M., Mader, M. & Schoen, H. (2021). Why Is the AfD so Successful in Eastern Germany? An Analysis of the Ideational Foundations of the AfD Vote in the 2017 Federal Election. Polit. Vierteljahresschr. 62, pp. 69–91.

Roemmele, A., Gibson, R. (2020). Scientific and subversive: The two faces of the fourth era of political campaigning. New Media & Society, 22(4), pp. 595-610.

Schmitt-Beck, R. (2021). Wahlpolitische Achterbahnfahrt. Wer wählte wen bei der Bundestagswahl 2021? Aus Politik und Zeitgeschichte 71(47-49), pp. 10–16.

Venghaus, S., Henseleit, M. & Belka, M. (2022) The impact of climate change awareness on behavioral changes in Germany: changing minds or changing behavior? Energ. Sustain. Soc. 12, 8.

citer l'article

Andrea Römmele, Parliamentary election in Germany, 26 September 2021, Mar 2022, 124-128.

à lire dans cette issue

voir toute la revue