Parliamentary election in Iceland, 25 September 2021

Eva H. Önnudóttir

Professor of Political Science at the University of IcelandIssue

Issue #2Auteurs

Eva H. Önnudóttir

21x29,7cm - 167 pages Issue 2, March 2021 24,00€

Elections in Europe : June 2021 – November 2021

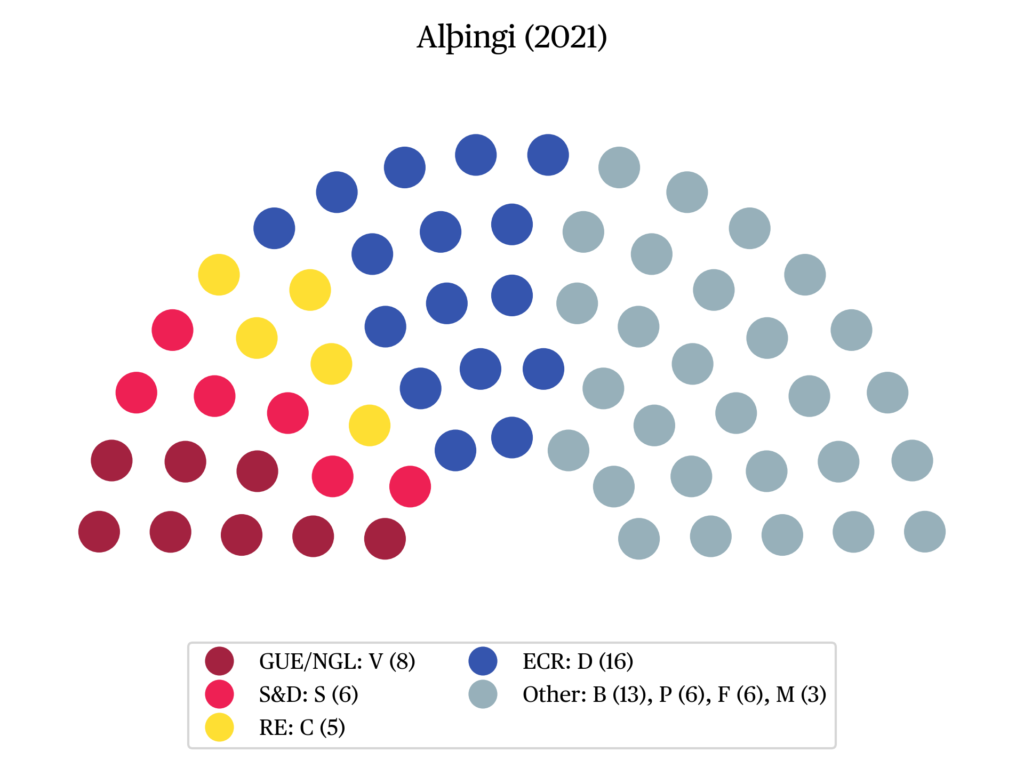

A parliamentary election took place in Iceland on the 25th of September 2021. Turnout was 80.1%. In the election the government coalition survived with a slight increase in its’ combined majority, and it is the first government that survives an election in Iceland since the collapse of the country‘s financial system in 2008 following the Great Recession. Since then, politics have been turbulent with three early elections in 2009, 2016 and 2013, and only two government coalitions have survived their whole term, including the incumbent government in the 2021 election. The 2009 government was brought down after months of protests following the economic crash, while the government coalitions that did not last for the term broke down due to scandals concerning ministers in the government (e.g. Harðarson and Önnudóttir 2018). The incumbent coalition was formed following the 2017 election when eight parties were elected to the parliament. The coalition is unusual in the sense that it includes three ideologically distinct parties, the Left-Green Movement (a left-wing party), the Progressive Party (a centre party) and the Independence Party (a right-wing party).

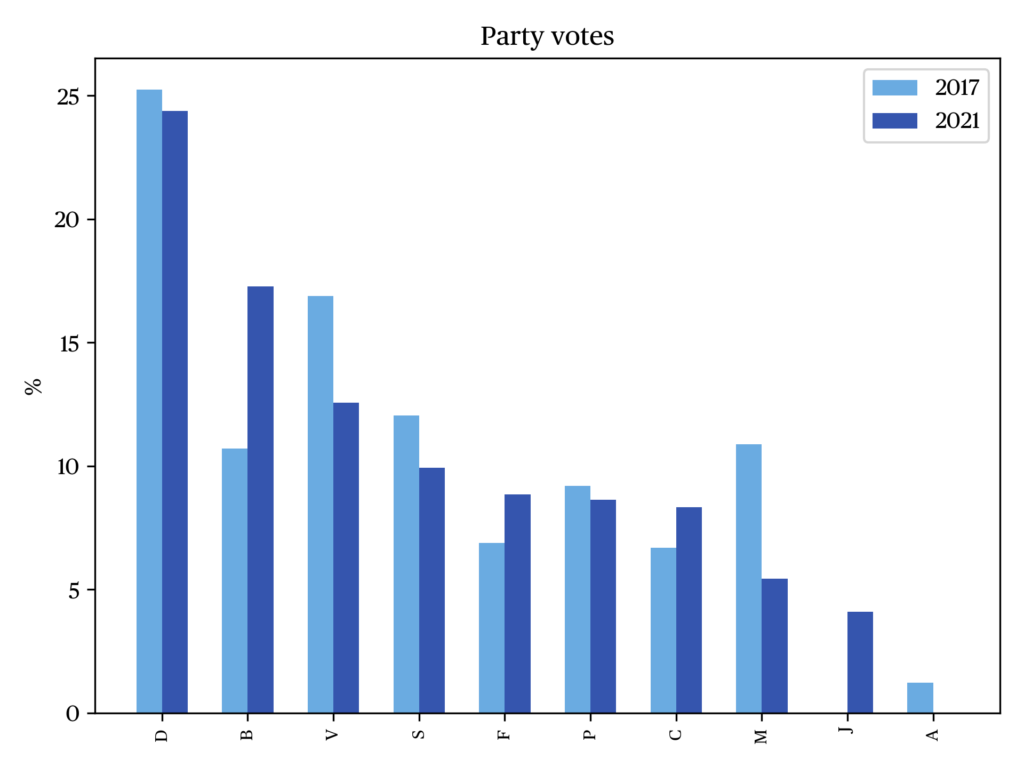

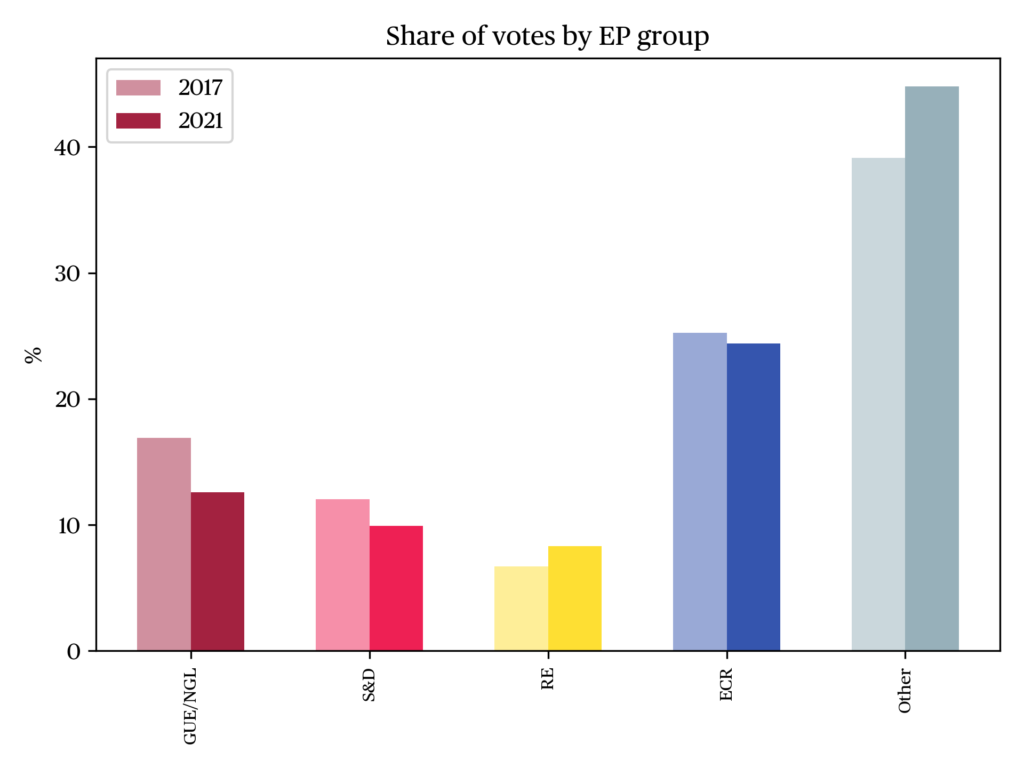

Among the government parties, the Progressive Party (B) was the main winner of the election, increasing its’ electoral support by 6.6 percentage points, while the Left-Green (V) and the Independence Party (D) lost support (-4.5 and -0.8 percentage points) (see Figure 1). Ten parties fielded candidates nation-wide, the eight parliamentary parties and two new parties, the Socialist Party (J) and the Liberal Democratic Party (O), and one party, Responsible Future (A) fielded candidates in one constituency. None of the three new parties got enough votes to reach the electoral thresholds, but for a party to get elected it must either reach a 5% threshold of the vote nation-wide or have a member elected in one of the six constituencies in Iceland. Prior to the election, polls had indicated that the Socialist Party would get between 6 to 9% of the vote, but their final result gave them 4.1% and no MPs. The two other new parties got less than then 0.5% of the vote. Among the opposition parties the People’s Party (F — a centre-left welfare party) and the Reform (C — a centre right liberal party) increased their support slightly (+1.9 and +1.6 percentage points), while the three other opposition parties, the Social Democratic Alliance (S, -2.2 percentage points), the Pirate Party (P, -0.6 percentage points) and the Centre Party (M, -5.5 percentage points) lost support. The result of the election was largely in line with what the polls had shown prior to the election, however with some twists. For example, the government parties seem to have been systematically underestimated in the polls, while some of the other parties (e.g. the Pirate Party and the Reform) were systematically overestimated. These discrepancies could be due to several reasons, e.g. whether that is due to systematic errors in the polls or that there were certain trends among voters in whom to vote for in the last days before the election.

The election campaign during covid

The election took place during covid times. However, the pandemic and how to deal with it was not an electoral issue. That could be due to that at the time of the election over 70% of people living in the country had been fully vaccinated. Also, in general people were happy with how the government and health care authorities had handled the covid crisis1. The government had largely followed the advice of the health care authorities when fighting the pandemic, and it was the scientists that were at the forefront of the fight, e.g. in regular briefings on TV, while the government ministers were not in the limelight. The government had increased spending and support to firms that were suffering due to the crisis and on both fronts, how to fight the pandemic and the economic actions taken, the government’s actions were largely supported by the opposition parties. Thus, covid and how it had been dealt with was not a divisive issue in the election campaign.

Instead, the main issues that the voters said to be of importance were about the health care system, the economy, social welfare and living standards, and environmental issues and climate change2. Respectively these were the main issues discussed in the election campaign. Even if covid and the government’s response to the pandemic was not an issue of the campaign, the impact of the pandemic was reflected in the discussions about the status of the health care system, the economy, and social welfare and living standards. In the case of the health care system the pandemic had brought to light shortcomings in the national health care system e.g. it being short of staff and that it was already overcrowded prior to the pandemic when it came to bed space. As in other countries, the economy was suffering due to the pandemic, unemployment increased, and businesses closed either temporarily or permanently. Thus, it is not a surprise that those issues and how to deal with them were one of the main issues of the electoral campaign and the discussion lined up on the ideological left-right scale about what would be the proper actions of the government.

One could say that the fifth main issue of the campaign was whether the government would survive or not. The opposition parties campaigned for a change in government, which is of course not unusual. What was more unusual is that even if the three government parties from left to right disagree about policies of the main issues of the election, e.g. about how to run the health care system and how much public funding the government should divert to businesses so they can stay afloat during the covid pandemic, the parties stood united advocating for a continuation of their coalition and stability in Icelandic politics.

Why certain parties fared better than others as a result of their campaign can only be speculated on at this time-point. However, it can be assumed that the government parties were successful in advocating for stability and a continuation of their coalition. Given that the only government party that increased its support, was the centre Progressive Party, might indicate that voters who supported a continuation of the incumbent government opted for the party in the middle as a strategy to keep the government in power. Meaning, instead of giving the right or the left-wing government parties their support, which might have resulted in a change in the government (to the left or the right), voters opted for the government party in the middle and by that increasing the probability that the government might continue.

A rural-urban divide

Historically the rural-urban cleavage, a conflict between the interests of urban and rural areas, has been one of the main cleavages in Iceland (in addition to the economic left-right cleavage). In Iceland the largest urban area includes the capital and the surrounding towns. For example, in 2016, 63% of Iceland’s voter population (332,529) resided in the capital area with the rest of the voters being scattered around the country in smaller towns, villages and rural areas.

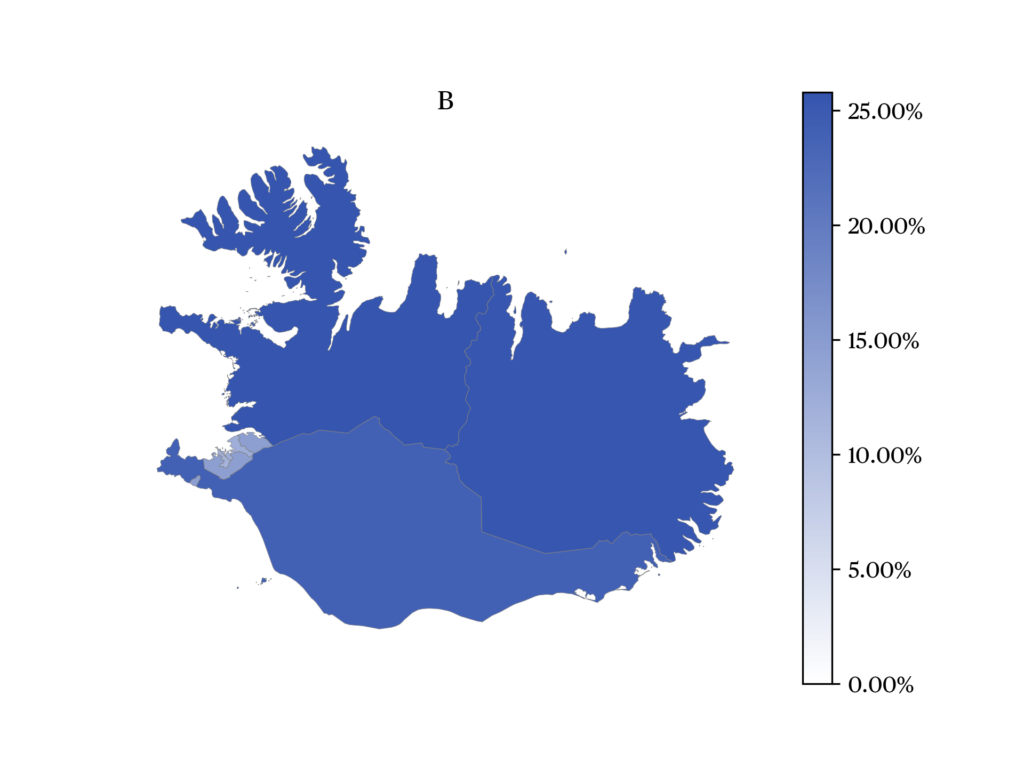

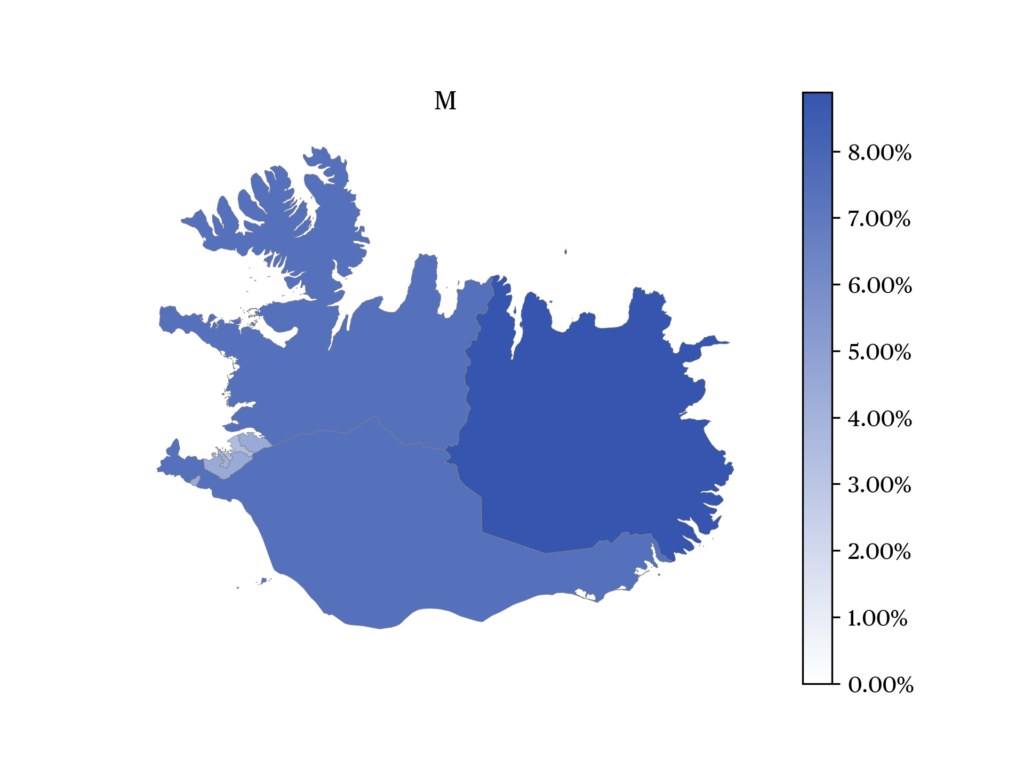

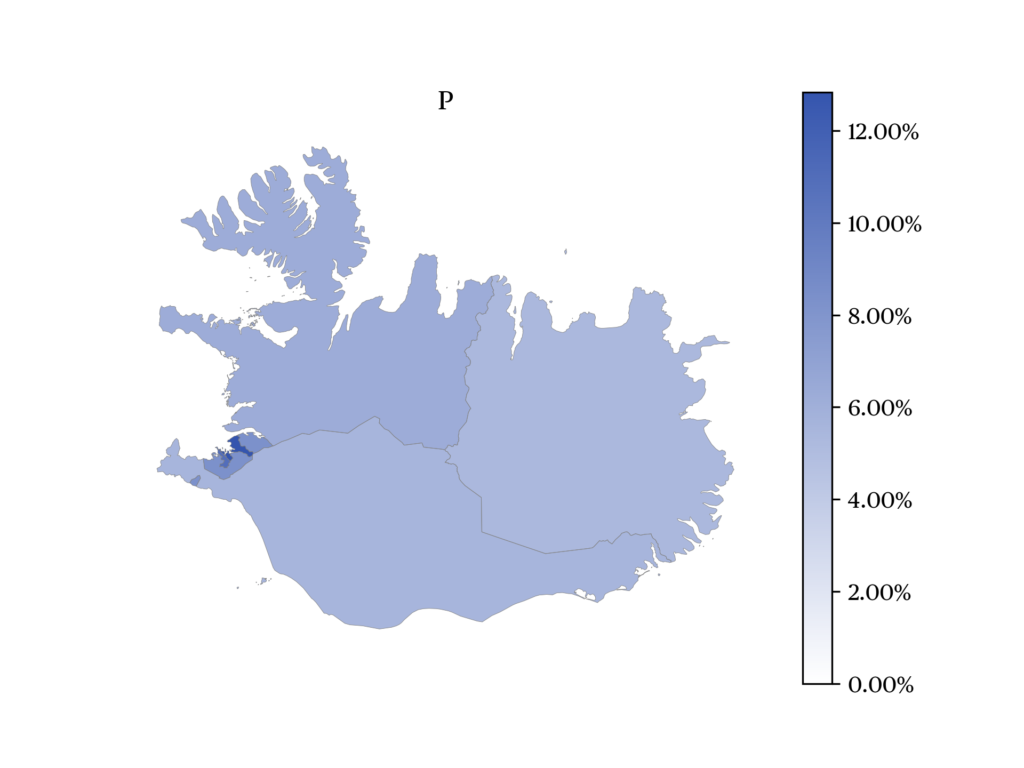

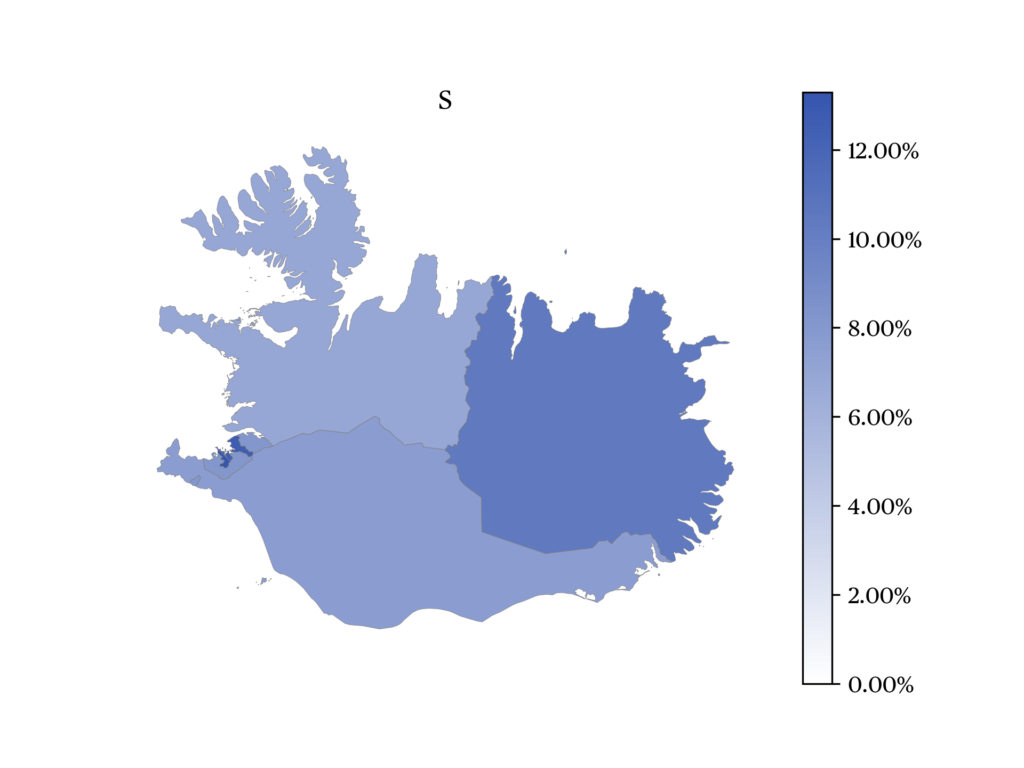

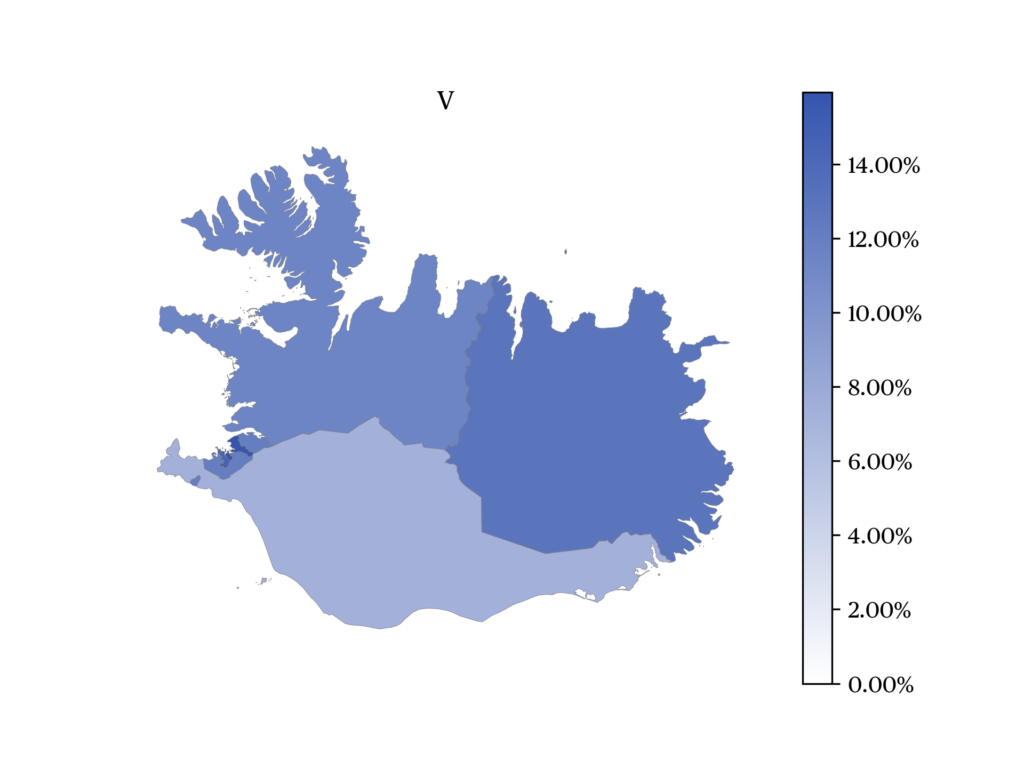

The six constituencies in Iceland are equally divided between the capital area, with three geographically small but urban constituencies (Reykjavik North, Reykjavik South and South West), and the countryside, with three rural constituencies (North West, North East and South), that cover most of the country. Historically, the countryside has been overrepresented in the Icelandic parliament. After the latest changes in the electoral system, which came into the effect with the 2003 election, this disproportionality between the capital area and the countryside was reduced to some extent but not eliminated. This rural-urban divide is reflected in the support of the parties, for example the Progressive Party and the Centre Party (see Figures 2 and 3) both have more support in the countryside compared to the capital area, while parties such as the Pirate Party, the Social Democratic Alliance and Left-Green Movement are stronger in the capital (see Figures 4, 5 and 6).

The election and recount

For the first time in the history of established democracies it seemed that female representation would exceed 50% (33 out of 63) of the MPs after the votes had been counted for the first time around. That only lasted for a few hours. After a recount in one of the constituencies (North-West) female representation dropped down to 48% (30 out of 63 MPs). This recount did not change the total number of seats won by each party, but it changed the allocation of adjustment seats within parties. At first it seemed that this recount would not be an issue other than changing the allocation of adjustment seats within parties. However, once it got out that the ballots had been left in a room, in which the staff at the hotel where the count took place had access to between the two counts, and that the ballot boxes had not been sealed as the election law in Iceland requires, people started to question the result of the election. One candidate decided to press charges to the police and several candidates and voters decided to press charges to the parliament, questioning the results of the election in the North-West constituency. The police investigation led to that the election officials in charge of the election in North-West were all fined for breaking the election law concerning the preservation of the ballots. As a result of the investigation of the parliament that took over a month, three proposals were voted on in the parliament. Two of the proposals were that a re-election should be held in the whole country or in the North-West constituency and they were both rejected. The third proposal, that the result of the recount should be valid, was accepted.

a • Results of the Progress Party (Framsóknarflokkurinn, B)

b • Results of the Center Party (Miðflokkurinn, M)

c • Results of the Pirate party (Píratar, P)

d • Results of the Social-Democratic Alliance (Samfylkingin, S)

e • Results of the Green-Left movement (Vinstrihreyfingin – grænt framboð, V)

The electoral system and bonus MPs

In 1999 there was made a change in the constitution that made it possible to make changes in electoral law that would guarantee equality between parties – without changing the constitution as was before. Prior to this change the Progressive Party had always been overrepresented in the parliament due to that the electoral system favoured the rural areas. At first this change was successful in the sense that in the 2003, 2007 and 2009 elections, all parties that reached the threshold to get elected were allocated MPs that reflected their share of votes. However, in 2013 this changed when the Progressive Party obtained a bonus MP at the cost of the Left-Green Movement, and this has been repeated in every national election since then. In 2016 the Independence Party got one bonus member from the Left-Greens, in 2017 the Progressive Party got a bonus member from the Social Democratic Alliance and in 2021 it got a bonus member at the cost of the Independence Party. The parliament can easily eliminate this discrepancy between votes and MPs, by changing the electoral law. All parties say that they support equality between parties. However, the parliament has not yet corrected this discrepancy that has now occurred four elections in a row.

Party system fragmentation

Prior to the Great Recession in 2008 the number of parties in the Icelandic party system was rather stable with four main parties, the Left-Green Movement, the Social Democratic Alliance, the Progressive Party and the Independence Party, and usually with one minor party in the three decades prior to the crisis. Until the 2013 election, apart from 1987, the number of effective parliamentary parties was from 3.2 in June 1959 to 4.2 in 2009. Since then, the number of effective parliamentary parties has increased, first to 4.4 in the 2013 election, to 5.1 in 2016, 6.5 in 2017 and 6.3 in the 2021 election. Thus, in the last decade party system fragmentation has increased. That has created challenges for the parties, one of them being that more than two parties are needed to form a government coalition as was the norm prior to the economic crisis.

Government formation

All three leaders of the government coalition parties stated in the campaign that their first option would be to continue their coalition if their majority would hold. Shortly after the election they started formal negotiations for a continuation of their coalition. The negotiations took two months, and at the end of November it was announced that Katrín Jakobsdóttir, the leader of the Left-Green Movement, would continue as prime minister. Katrín Jakobsdóttir has been by far the most popular politician in Iceland for a long time. Surveys show that approximately 40-50% of people prefer her as prime minister, even if they do not support her party, which got 12.6% in the recent election. It is safe to assume that her popularity, outside of the ranks for her own party, makes her the most credible leader of the ideological distinct parties in the government.

What the future holds for the next government

One of the key challenges for the next government will be to steer the economy on a path of recovery after the recession due to the covid pandemic. In 2020 there was the largest contraction in economic growth since 1920. The government’s response was among other things to divert public funding to businesses so they could either stay open or would stay afloat while they had to shut down due to the pandemic. In the next few years we might see increased public spending to speed up the recovery of the industries, specifically the tourism industry which has been a major source of income in Iceland in the last ten years.

Many people predicted that the current government would not last for the term when it was formed following the 2017 election. They were wrong, the government survived the whole term. Some say that the Covid pandemic saved the government as the fight against it removed potentially dividing issues from the political sphere. The continued government coalition has a good chance of surviving as they have already worked together for four years laying a solid foundation for their cooperation in the current government.

Literature

Önnudóttir, E. H. & Harðarson, Ó. Þ. (2018). Political cleavages, party voter linkages and the impact of voters’ socio-economic status on vote-choice in Iceland, 1983-2016/17. Icelandic Review of Politics and Administration, special issue on power and democracy in Iceland, pp. 101-130.

Önnudóttir, E. H., Helgason, A. F., Þórisdóttir, H. & Harðarson, Ó.Þ. (2022). Politics Transformed? Change, Fluctuations and Stability in Iceland in the Aftermath of the Great Recession. Routledge.

Harðarson, Ó.Þ. and Önnudóttir, E.H. Election report Iceland. (2018). Scandinavian Political Studies, 41(2), pp. 233-237.

citer l'article

Eva H. Önnudóttir, Parliamentary election in Iceland, 25 September 2021, Mar 2022, 152-156.

à lire dans cette issue

voir toute la revue