Parliamentary election in Malta, 26 March 2022

Mark Harwood

Director of the Institute of European Studies at the University of MaltaIssue

Issue #3Auteurs

Mark Harwood

Issue 3, March 2023

Elections in Europe: 2022

Introduction

Malta is the EU’s smallest and most densely populated country, situated south of Italy in the central Mediterranean. A British colony for 160 years, it gained independence in 1964 and joined the EU in 2004. A unitary state, its political system is based on the Westminster model and its main political parties were established over a century ago (Harwood 2014). After independence all minor parties lost their seats in parliament and since 1966 Malta has been a two-party system, only the Social Democrats and Christian Democrats being elected to parliament, meaning that governments always enjoy absolute control over parliamentary business (the Democratic Party entered parliament in 2017 in an electoral coalition with the Christian Democrats but lost their seats in 2019 when both its MPs resigned from their party). Through patronage, the political parties have become exceptionally powerful and have consolidated their grip on the country through ownership of the main commercial TV channels, newspapers and online media.

While powerful, the parties must satisfy a broad spectrum of interests if they hope to win an election because the electoral system entails few wasted votes; Malta has utilised the Single Transferable Voting (STV) system since 1921, a ranked preferential system based on multiple member constituencies with the country divided into 13 districts with 5 seats available for each district. STV allows voters to rank candidates, normally up to the number 10 with the candidate listed ‘1’ being their preferred candidate, and then based on the valid votes in each district, a quota is established which candidates must reach to be elected. Few candidates automatically reach this quota and most are elected after repeated rounds of counting where they inherit the surplus votes of the candidates who performed best (and met the quota) or inherit the votes of those who performed worst (and who were eliminated). Voters can spread their preferences across multiple parties but their first preference denotes their support for the party of the candidate they have voted for and will determine the final balance of seats in parliament.

To ensure that the composition of parliament reflects this balance and assuming that party candidates may have won more seats than the final balance entitles their parties to, additional seats are allocated and, consequently, parliament often has more than the 65 seats stipulated in the General Election Act (2021). The result is an electoral system where few votes are wasted but voters might not always know who they elected as their ballot might have included several candidates who eventually reached the quota and gained a seat. While protracted, for over 50 years turnout was in excess of 90%, indicating popular support for the electoral system.

The 2022 General Election

Before beginning a discussion of the 2022 general election, two points should be mentioned to provide a wider context to the election. The first relates to the 2018 constitutional amendment lowering the voting age to 16, injecting a degree of uncertainty as to how the 16-18 age group would engage with the elections. Second, in an attempt to address the under-representation of women in Maltese politics, constitutional amendments enacted in 2021 meant that, should the final tally of female members of parliament not reach 40% of the total, that 12 extra seats would be added to the final number of seats so as to increase the number of ‘the lesser represented gender’ in parliament, the extra seats being distributed equally between the two parties (Constitution of Malta 2021, No. 52A). Interestingly, few people knew about this new system and many were surprised when the mechanism was put into effect in March 2022.

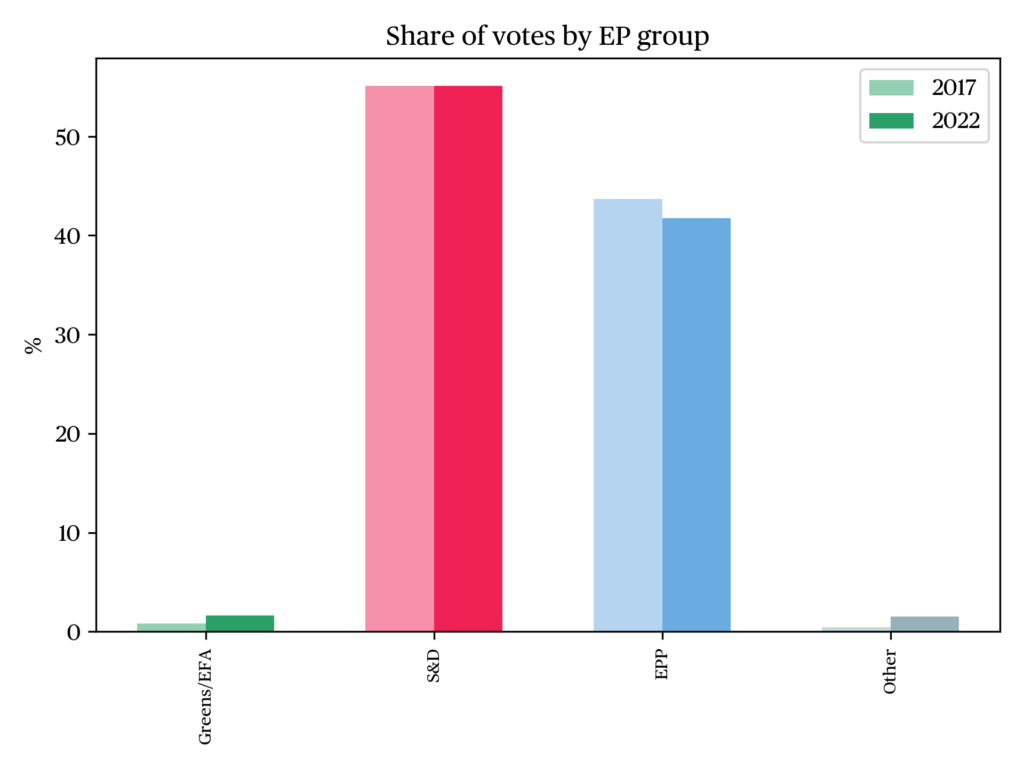

The Government announced the election on 20 February with the date set for 26 March.1 The ruling Social Democrats, the Labour Party (PL, S&D), had been in power since 2013. In that year it had won the largest majority in Malta’s post-independence history, a feat it repeated in 2017. This was a significant reversal of fortunes for a party which had, effectively, been in opposition since 1987, undermined by its staunch anti-EU membership policy.2 Since 2013 the country’s economy has grown strongly with one of the highest growth rates in the EU and economic growth has been accompanied by social reforms with Malta now the European leader for LGBTIQ rights (ILGA-Europe 2021) though abortion remains taboo, reflective of the continued influence of the Catholic Church. The ruling PL was also buoyed by its COVID-response measures which had seen Malta become the first EU country to reach herd immunity in 2021 and predicted by the Commission to be the EU economy least impacted by the pandemic. However, the PL government also had to contend with negative press, especially following the murder of a prominent journalist in 2017 and revelations in the Panama and Paradise Papers which saw the PL prime minister resigning in 2020, replaced by Robert Abela (PL), the son of a former president. On the other side of the House, the Christian Democrats, the Nationalist Party (PN, EPP), in power from 1987-1996 and 1998-2013 has struggled to re-establish its place in Maltese politics, having had 4 different leaders in the last 10 years and riven by discord on social progress as the party tries to balance traditional and more progressive party members. Going into the 2022 general election, parliament was composed of 67 members, 36 for the PL, 28 for the PN and three independents (two being the former members of the Democratic Party and the last being a former PL minister) (Parliament of Malta 2022).

The Parties, Candidates and Campaigns

Six parties contested the 2022 general election with the ruling PL fielding the largest number of candidates with 122 while the PN fielded 108 candidates. ABBA (ultra-conservative), established in 2021, fielded 28 candidates across all thirteen districts, the AD+PD party (a merger of the Democratic Alternative (commonly referenced as the Green party) (AD, EGP) and the Democratic Party (PD, ALDE)) fielded 20, the People’s Party (PP) (far-right) fielded 15 while Volt Malta (a branch of Volt Europa – European federalists) fielded only 4 candidates and were not represented across the 13 districts. There were also four people who stood as independent candidates (Electoral Commission 2022a).

The general consensus across the media was that the 2022 general election campaign was lacklustre and overshadowed by the war in Ukraine with a notable shift to online advertising as the Maltese remain some of the highest users of social media in Europe, second only to Cyprus (European Commission 2020). The main parties ran highly confusing advertising campaigns with party logos missing, party slogans which never took hold and were difficult to differentiate (the PL went with Malta Flimkien (Malta Together) while the PN went with Mieghek ghal-Malta (With You for Malta)) while polls maintained that a PL victory was inevitable. The PL promised continued economic growth, free childcare, a slash in corporate tax rates and investment in green areas. In a dubious move, cheques rained down on the country in the weeks before the election as every household received one-off tax rebates and ‘supplementary cheques’ which compensated lower income workers and pensioners most. The PN, eager to portray itself as capable to maintain the country’s economic growth, promised a ‘€1 billion investment programme’, building of a tram system to combat the growing problem of traffic congestion and the creation of more green areas. Outside the main parties, the AP+DP focused on promising a ‘green’ clean sweep of the political system while ABBA, with several candidates linked to anti-LGBT and anti-migrant statements in the past, spent most of the time warning against the introduction of abortion, a warning echoed by PP candidates which also included individuals previously associated with far-right policies, primarily anti-migrant.3 On the other side, Volt Malta was of note for being the first party to advocate in favour of the decriminalisation of abortion. Of the independent candidates, even the promise of Nazareno Bonnici, a repeat candidate who often helped alleviate the intensity of elections with his irreverent statements and pledges, struck an unpleasant note when he promised to provide €4000 to women for breast augmentation, a pledge made on International Women’s Day. Against the war in Ukraine, the election seemed superficial, the messaging incoherent and popular engagement seemed to falter, the election never actually ‘taking off’.

The Results

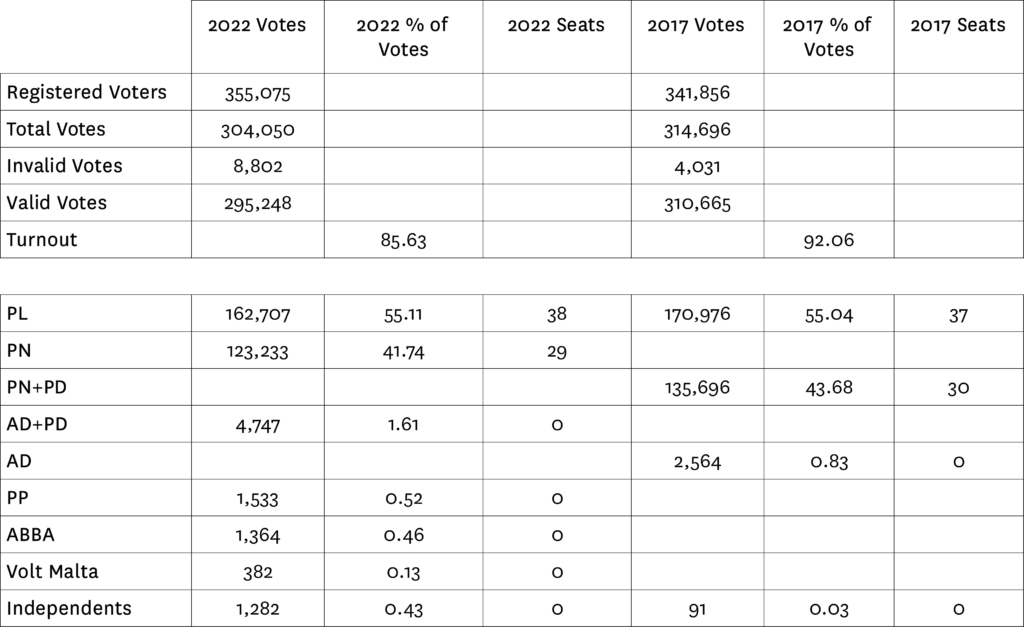

Voting took place on Saturday 26 March and counting began soon after 9:30 am on Sunday 27. As in previous elections, counting began with ballots being opened in public view at the Counting Hall in Naxxar. From this exercise, party members can begin to predict the final vote by counting a sample of first preference votes and within 90 minutes and in an unprecedented manner, the PM phoned into the state broadcaster and announced on-air that his party had won. Celebrations began soon after with the main focus being on calculating the margin of victory for the Social Democrats. That said, as the morning progressed it became increasingly apparent that the 2022 election was going to be seismic for the drastic drop in turnout, a key variable as the main parties are synonymous with pushing loyalists to vote, often using ‘street leaders’ to monitor who has not yet voted before calling and encouraging them to vote. Even though pollsters had predicted that turnout would dip, no one could predict it would drop so steeply; Malta has always had turnout for general elections above 90%, reaching a peak of over 96% in 1996 and 2003. For the first time since 1966, turnout dropped below 90% and fell to a dramatically low 85%, see Figure a. Some continued to argue that this was still exceptionally high but the fact that the PM, in his first address after being sworn in, spoke to those who did not vote indicated how serious this development was, seeming to bring into question the two parties’ hold over the electorate. Ultimately, for a political system where each vote counts, the loss of 15% of the electorate brings into question the tried and tested methods of the main parties and the overall support for the electoral system. While analysis remains ongoing, allegations of misconduct by members of both parties, persistent negative press (Malta’s greylisting by the FATF and the European Commission’s infringement procedure against Malta’s ‘golden passport scheme’ both happened in 2021), a growing number of independent news-portals and an economic boom which actually frees people from the need for seeking political favours might help explain the record drop in turnout.

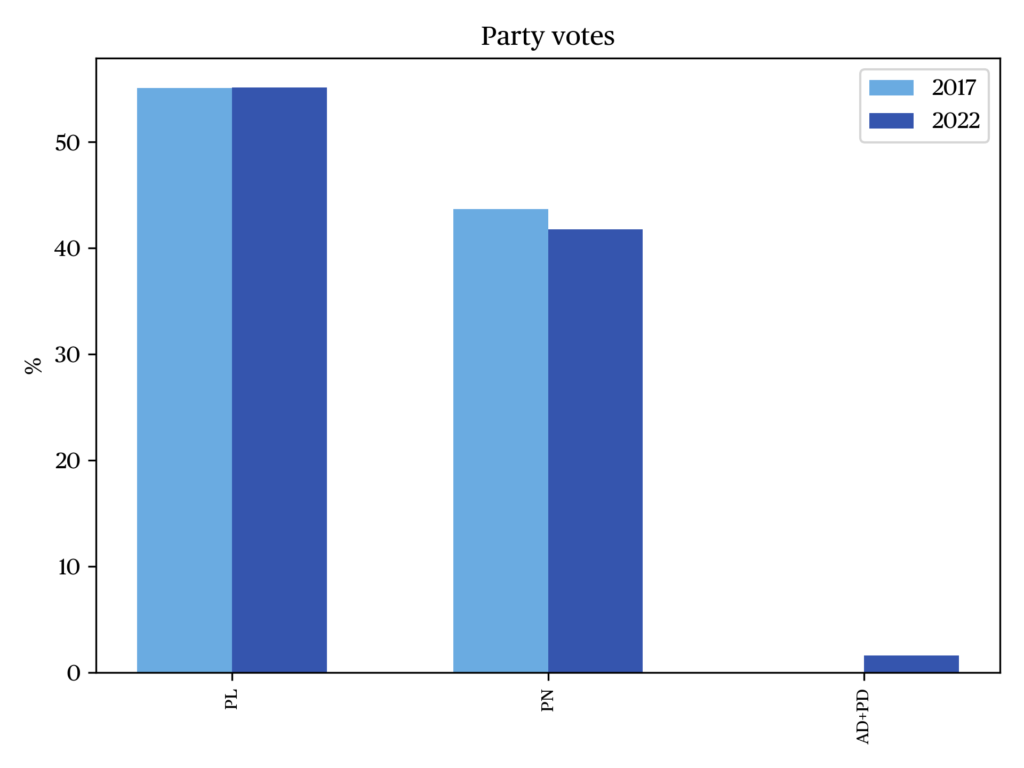

Beyond the issue of turnout, the result was far from convincing for any party. While the PL scored a notable victory over the PN with a majority of nearly 40,000 votes, in actual fact it won fewer votes in 2022 than it did in 2017 despite the number of eligible voters increasing due to the voting age being lowered. As Figure a shows, the PL lost 8,000 votes while the PN lost even more dropping by 10,000 votes (if we do not include the 2017 votes for PD candidates with which the PN had formed an electoral coalition). Outside the main parties, the performance of AD+PD was of note, not simply because it gained the third largest number of votes but because it indicated that AD remains a united party though they have lost some of their most prominent members while PD, which was synonymous with its two MPs before their resignation, remains a viable party with the amalgamation of the two parties also appearing to be working. Outside the main parties, PP and ABBA failed to gain much traction with the electorate while Volt Malta performed poorly, potentially as a consequence of its pro-abortion stance or because of the fact that it did not run across all districts so was precluded from participating in several, high profile party-leader debates.

In terms of gender balance, a central aim of the election was to increase female representation but with only ten women winning a seat (and often through casual elections), it was a very poor showing and while female representation was bolstered by the additional 12 seats, it will still mean that only 25% of the seats in parliament are occupied by women.

Conclusion

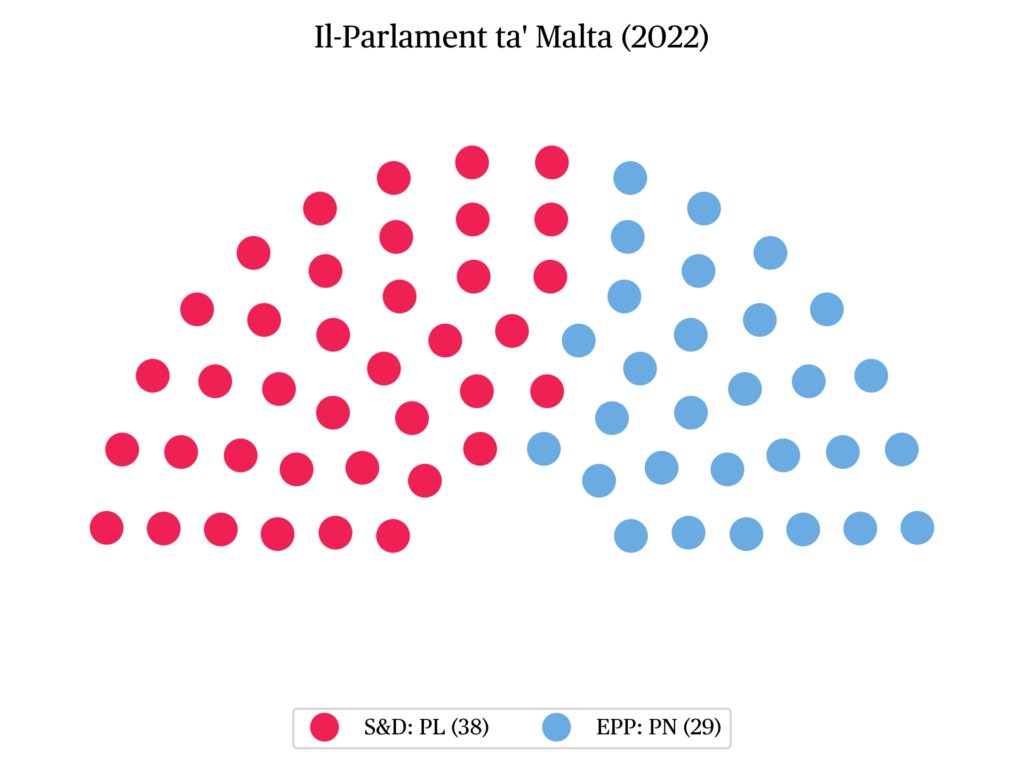

The final tally of the general election of 2022 sees a parliament of 79 members, 44 for the PL and 35 for the PN (which includes the extra seats for female candidates). The PM, appointed after the resignation of Joseph Muscat (PL), will be empowered by the result as indicating his ability to win the popular vote. The leader of the PN has announced he will seek re-election as party leader but the party remains a shadow of its former self. While the leader of the PN might manage to re-establish his party, many PN supporters are turning their gaze to Strasbourg; Roberta Metsola, the PN MEP who was elected President of the European Parliament in 2021, kept a low-profile during the campaign but many in the party will see her as the only viable leader for the future and though she has not indicated a wish to return to national politics, her shadow will loom large over the party. Outside the interests of the main parties, the Maltese election of 2022 will become a turning point in Maltese politics due to the historic disengagement shown by the electorate. The main parties will scramble to understand why 15% of the population stayed away (as well as the doubling of invalid votes) and it will be the shadow of the disengaged voter which will dominate Maltese politics over the next five years.

Nota bene: These graphs/maps show first preference votes by constituency. Northern Ireland uses the Single Transferable vote (STV) system.

References

Constitution of Malta (2022). Constitution of Malta. Online. Retrieved 30.3.22.

Electoral Commission (2022a). General Election 2022 – All Nominations. Online. Retrieved 30.3.22.

Electoral Commission (2022b). General Elections 2022 Results. Online. Retrieved 30.3.22.

European Commission (2020). Directorate-General for Communication, Media use in the European Union : report. Online. Retrieved 30.3.22.

General Elections Act (2021) Chapter 354 General Elections Act. Online. Retrieved 30.3.22.

Harwood, M. (2014). Malta in the European Union. UK: Palgrave.

ILGA-Europe (2021). Rainbow Europe. Online. Retrieved 30.3.22.

Parliament of Malta (2022). Political Groups. Online. Retrieved 30.3.22.

citer l'article

Mark Harwood, Parliamentary election in Malta, 26 March 2022, Oct 2022,

à lire dans cette issue

voir toute la revue