Parliamentary elections in Norway, 13 September 2021

Stine Hesstvedt

Research fellow at the Institute for Social Research in OsloIssue

Issue #2Auteurs

Stine Hesstvedt

21x29,7cm - 167 pages Issue 2, March 2021 24,00€

Elections in Europe : June 2021 – November 2021

Introduction

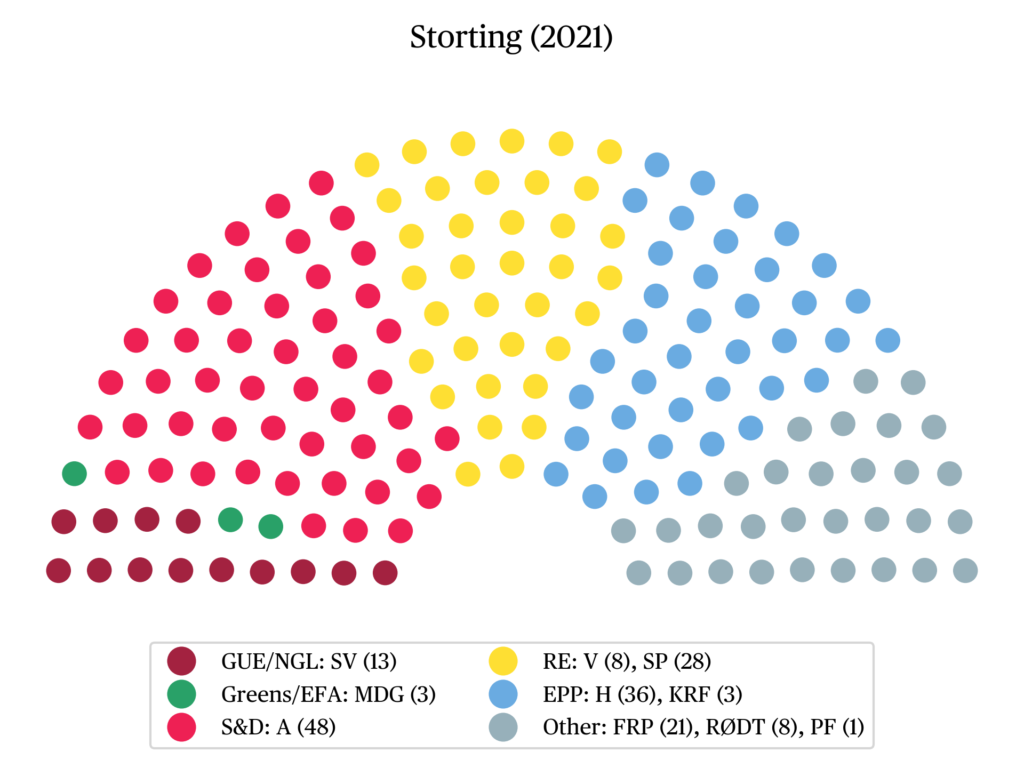

After eight years in power, the Conservative-led coalition government of Erna Solberg had to step down on the 13th of September 2021. The left bloc in Norwegian politics — headed by the Labour Party leader Jonas Gahr Støre — had received an overwhelming share of the votes: Results revealed a historic majority to the left-bloc with 100 out of 169 seats in the Norwegian Storting. While the polls had predicted a left-wing majority for quite some time, the election results nonetheless offered a few surprises. For one, the fragmentation of the party system reached new heights in the evening of September 13th. Second, and relatedly, the election left the left-bloc historically fragmented, as the former communist party Rødt multiplied support and surpassed the electoral threshold. Third, the popular support of the former right-wing governmental parties declined more than expected, especially for the populist right party Fremskrittspartiet and the Christian democratic party Kristelig Folkeparti. Moreover, the election campaign took some unexpected turns; the ‘code red’ UN climate report hit in the midst of the campaign in addition to a political scandal related to MPs’ housing benefits. Lastly, government formation was unanticipated, as the negotiations resulted in a two-party, minority coalition between the agrarian Centre Party and the Labour Party – without the expected presence of the Socialist Left.

In the rest of this article, these key observations are laid out in greater detail. First, however, the next section provides a brief background to the election and describes key features of Norway’s party and electoral system.

The Norwegian electoral and party system: A brief introduction

Political cleavages and the party system

As an advanced social democratic state in Northern Europe, the Norwegian party system bears both resemblance and distinctness to other European countries. When political scientists Stein Rokkan and Seymour Lipset wrote their seminal work on early state formation and political cleavages in Western Europe (Lipset & Rokkan, 1967), the Norwegian political conflict structure was coined ‘multidimensional’ compared to other countries. As a former colony of Sweden and Denmark

1

with strong popular scepticism to urban elites; a vocal nationalist counterculture in the periphery; strong religious lay movements in rural areas; and a powerful working class movement, early state-building resulted in a distinct and multi-faceted political cleavage structure (ibid).

Decades after Rokkan and Lipset’s description, old political cleavages still and to some extent structure Norwegian party competition. As in other Western European countries, new issues related to immigration, climate change, and globalization have become salient and spurred new political conflicts (Hooghe & Marks, 2018). Also, as a wealthy, oil-producing welfare state with an open economy, issues related to Norway-EU relations/EEA and the oil and gas industry are examples of ‘new’ political conflicts with a specific Norwegian flavor (see Bergh, Haugsgjerd and Karlsen, 2021).

Today, Norway is characterized as a moderately polarized and fragmented party sytstem (Lijphart, 2012). As in other European countries, the Norwegian party system has gradually become more fragmented with an all-time high in the 2021 election (see below). Up until the election of 2013, the party system had traditionally consisted of seven parties. The left bloc includes three parties: the Labour Party (Arbeiderpartiet), the new left party Socialist Left (Sosialistisk Venstreparti), and the agrarian, centre-left Senterpartiet that represents rural interests. The right-wing bloc includes two centre-right parties – the Liberals (Venstre) and the Christian Democrats (Kristelig Folkeparti) – as well as the Conservatives (Høyre) and the right-wing Progress Party (Fremskrittspartiet). In 2013, two additional parties entered parliament with one MP each: the Green party (Miljøpartiet De Grønne), which proclaimed a neutral left-right position, as well as the former communist and currently radical socialist party, Rødt.

Party competition and government formations

Norwegian party competition has been — and still is — structured by the economic left-right dimension, with the Labour Party being the most dominant actor (but the party’s support has been declining, see below). In every election since the Second World War, the Labour party has received the lion’s share of the votes (in total 20 elections between 1945 and 2021), in total occupying 13 out of 21 prime minister posts in the period. Along with the other Scandinavian countries, Norway used to exhibit some of the highest levels of class voting in the world, and the two main competitors have mostly been, and still are, the Conservative party and the Labour Party. As such, competition adherse to a two-bloc logic: With the exception of a center-based government in the 1990s, political power has shifted between the left and the right.

As for party cooperation, coalition governments have become more common over time. Minority governments have also been the rule. While the Labour Party ruled as single-party cabinets until the 2000s, former Prime Minister Jens Stoltenberg (2005-2013) induced a three-party coalition between Labour, the Centre Party and the Socialist Left after receiving a decline in support.

When the former Prime Minister Erna Solberg took office in 2013, yet another historic coalition was born. The Conservative party was joined by the populist Progress Party in government, making Norway one of the first countries in Western Europe to be governed by a populist right-wing party. However, after the Liberals and the Christian Democrats joined in 2018-2019, the cooperation turned out to be fragile. The four-party majority coalition lasted until January 2020, when the Progress Party resigned due to discontent with the government’s immigration policy. Up until the election in September 2021, Solberg therefore ruled a minority government with the support of the Liberals and Christian Democrats.

The electoral system

Lastly, some details about the electoral system (see also Aardal, 2011). In particular, the 4 percent electoral threshold concerning 19 adjustment seats deserves notice, as it had important implications for the 2021 results. In short, Norway has a proportional (PR) electoral system where votes from 19 election districts are translated into a total 169 seats in parliament. 2 Of the overall 169 seats, 150 are district seats distributed according to the constituencies. In addition, 19 seats are so-called adjustment seats (also called levelling seats or compensatory seats). This is to compensate for the fact that the electoral system is skewed in favour of the peripheral electoral districts and the biggest parties. 3 As a result, the electoral system systematically disfavours the smaller parties; in particular the smaller parties that receive most of their support from the urban and populous electoral districts. To account for these biases and increase proportionality, 19 out of 169 seats therefore serve the purpose of adjustment. However, in order to compete for the 19 seats, parties need at least 4 percent of the national vote. This 4 percent requirement is — quite confusingly — referred to as the “electoral threshold”. In practice, a party may receive less than four percent of the national vote and lose out of the 19 adjustment seat competition, while still receiving some of the 150 constituency seats if its support is strong enough in a single electoral district. In the 2013 election, this was the case for the Greens and the Radical Left party Rødt, which entered parliament with one MP each from the capital Oslo, even though they received less than 4 percent at the national level. As we will see, this threshold had important implications in the 2021 election.

Run-up to the 2021 election: The long and short election campaign

When Norway entered the election year of 2021, things did not look too bad for the incumbent government of Erna Solberg. Indeed, winning the election and embarking on a third victory would have been most extraordinary in historical terms, as Norwegian prime ministers rarely sit for more than two terms. Nonetheless, after eight years in power, Erna Solberg started 2021 with quite a solid lead in the polls. One year earlier, the COVID-19 pandemic had thrown Norway into one of its most urgent crises since the Second World War. As elsewhere, the Solberg government had received a considerable rally-around-the-flag boost in support, and this effect retained well into the election year of 2021. However, when the vaccines arrived and the political agenda slowly started to normalize, the Left flank made a leap. By the summer, the pandemic boost to the government’s support had disappeared, and cards were turned.

Throughout the campaign, two issues that are consistently favourable for the left flank dominated the media’s agenda; namely social inequality, as well as discussions about rural areas and centralization policies. In addition, IPCC’s sixth climate report — with the alarming “code red” message — hit amidst the Norwegian campaign, dominating the traditional news press almost entirely for a week or two. For some time, then, commentators were convinced that the 2021 election would be the climate election (Aftenposten, 2021). However, in the end, the green parties did not receive a landslide of votes as expected after the UN report. While the reasons for this are manifold, there is no doubt that other issues entered the agenda; in particular a scandal about MPs’ housing benefits. The scandal broke the last week before the election, involving a range of MPs as well as the Christian Democrats Party leader, Kjell Ingolf Ropstad. According to the Aftenposten newspaper that brought the story, Ropstad had for years received free housing from the Norwegian Parliament on dubious grounds, and on purpose (although not illegally). While talks of fraud and prosecution were quickly rejected, Ropstad resigned as minister and party leader shortly before the election. The scandal did arguably steal some of the limelight in the crucial last week of the election campaign.

2021 election results: Some key elements

In short, the election results revealed an overwhelming majority for the Left in Norwegian politics and a sharp decline in support for the former governmental parties. Below, the outcome is summarized in four key points: 1) increased fragmentation of the party system, 2) a historic majority (and fragmentation) of the Left, 3) the steep decline in support to the former cabinet, and 4) the surprising outcome that the Green party did not surpass the electoral threshold.

Increased fragmentation of the party system

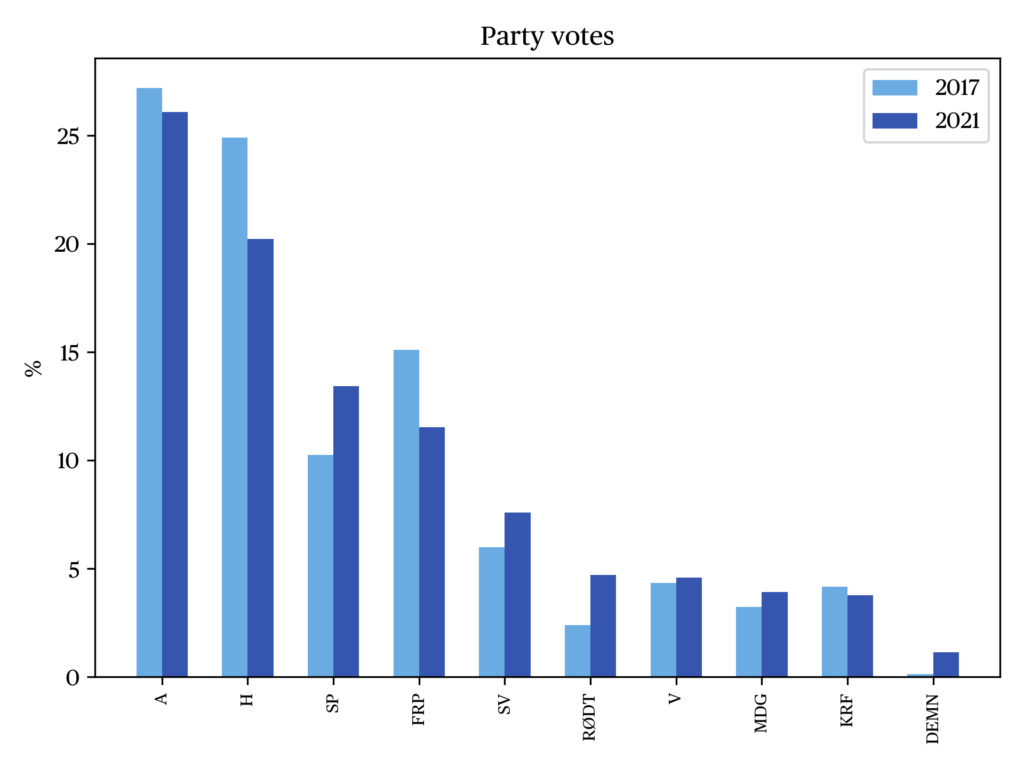

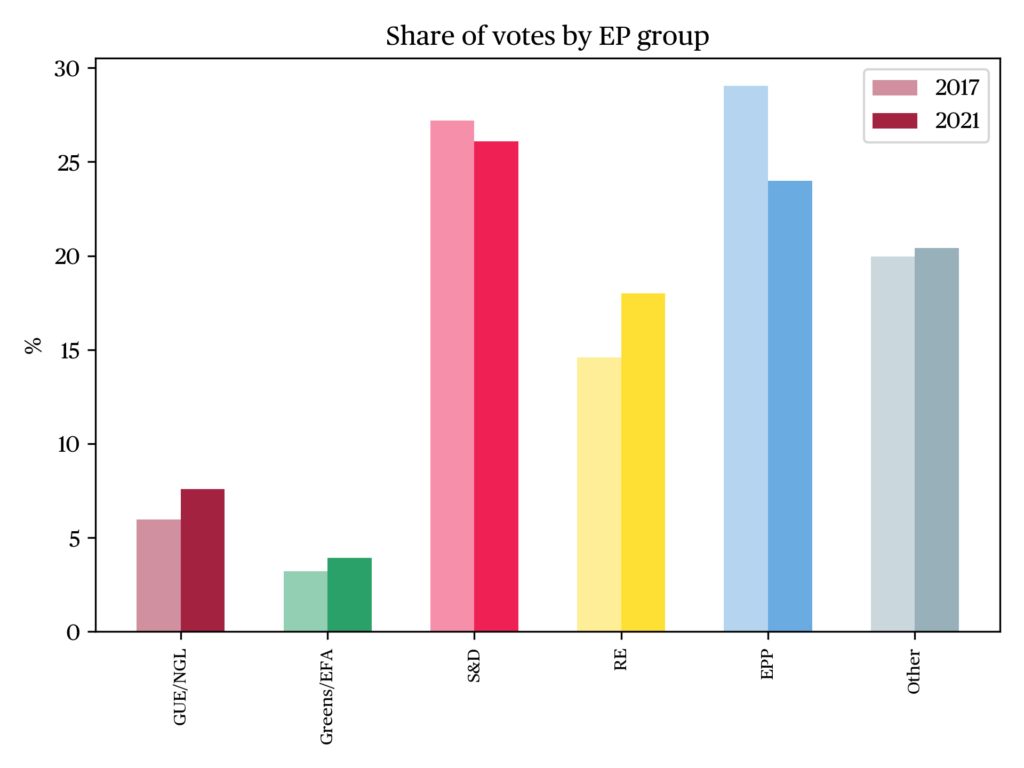

With the effective number of parties rising from just below 5 to 6.5 parties, the fragmentation of the Norwegian party system hit a new high on the night of 13th of September. The main factor driving this fragmentation was that the largest parties became smaller — namely the Labour Party, the Conservatives and the Progress Party, while middle-sized parties (the Center Party and the Socialist Left) became larger. Moreover, Rødt passing the threshold and the Christian Democrats failing to do so contributed to increased fragmentation. In addition, a new single-issue party campaigning for a hospital in Northern Norway (Pasientfokus) entered the parliament with one seat.

Overall, Norway followed a trend of fragmentation familiar elsewhere in Western Europe. It also seems clear that the parliament may have become more polarized after the election. For the first time in history, the Norwegian Storting comprises two weighty parliamentary groups at the far left as well as the far right: On the left flank, the former communist party Rødt, and on the right flank, the populist Progress Party.

The Left bloc’s historic majority (and fragmentation)

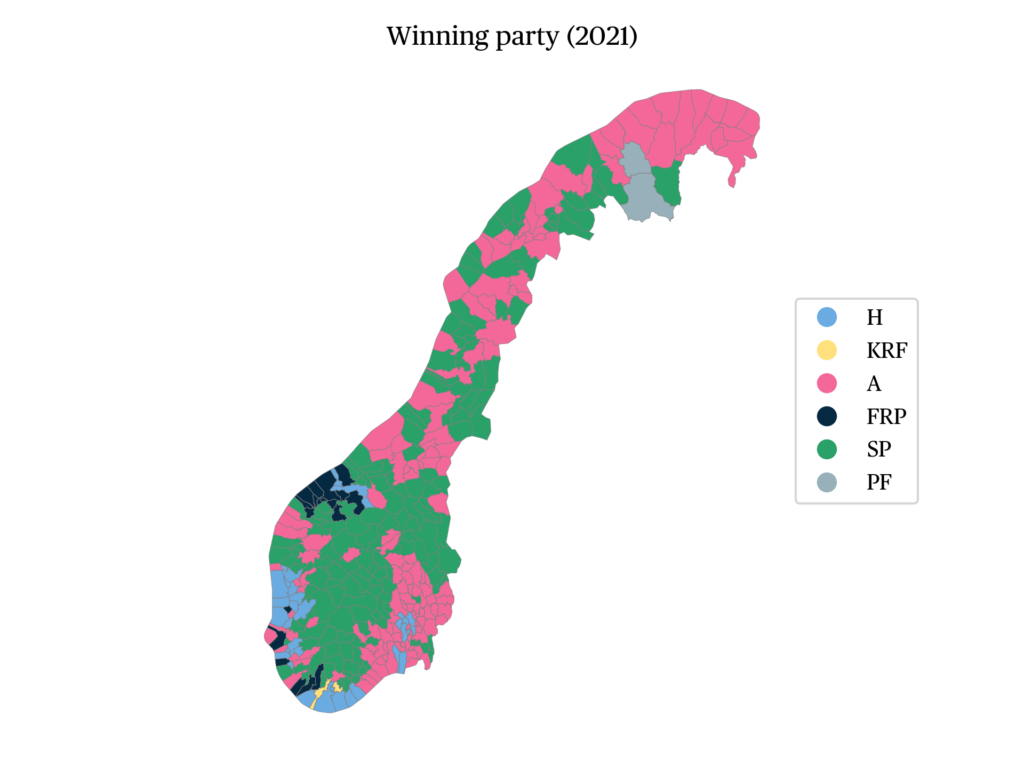

The five Left parties — the Labour Party, the Centre Party, the Socialist Left, the Red party Rødt, and the Greens —– received 100 out of 169 seats; the largest majority the left bloc had seen in years. While the election result was not particularly uplifting in absolute terms for the Labour Party (the party saw a slight drop in votes and lost one seat in parliament compared to 2017), it did much better than expected. About a year before the election, the party had seen polls down in the low twenties, and —for a short period — the Center Party was Norway’s biggest party. In the end, on Election Day the Labour Party managed to retain its much-needed support in the traditional and important strongholds in the industrial municipalities in middle of the country, as well as in the regions in the North. Overall, Jonas Gahr Støre’s Labour Party retained its position as Norway’s largest and expanded their lead in seats over the Conservatives compared to 2017.

As the third biggest party, the agrarian Senterpartiet could celebrate one of its best elections ever, with an increase of nine MPs (from 19 to 28) and the largest increase in support among all parties (3.2 percentage points). In particular, the party benefitted from opposition to the former government’s centralization reforms, that among other things concerned amalgamations of municipalities and administrative regions. As such, the Center Party’s leap in support was by and large driven by the high saliency of periphery issues, and its strong increase mainly came from voters in rural and peripheral municipalities.

To many commentators, the biggest winner of the 2021 election was the radical socialist party Rødt. Not only did the party obtain its best result ever; it was also able to surpass the adjustment seats threshold at 4 percent, which is vital for small parties as it implies allocation of adjustment seats (see above). Up until 2021, Rødt had twice been represented in the Storting with a single Member of Parliament; in 1993-1997 (the party’s predecessor Rød Valgallianse) and in 2017-2021 when the party leader Bjørnar Moxnes gained a seat from the capital Oslo. Up to 2021, however, Rødt — together with other small and newly established parties — had never been able reach the 4 percent national threshold for the much-needed adjustment seats. Thus, when the radical left party received 4.7 percent of the votes and increased their parliamentary group from 1 to 8 MPs, it secured a historic win. Interestingly, the party seems to have significantly broadened its voter base.

4

Up until 2021, the former communist party, which had abandoned explicit reference to revolution and Marxism in its party platform only a few years earlier, had a somewhat limited appeal to the highly educated in the largest cities. In this election, Rødt increased its support all over Norway– both in rural and urban areas, in the South and North. Quite tellingly, Rødt’s support grew in all but one municipality in Norway (355 out of 356).

Furthermore, the Socialist Left Party had a good election, increasing their support by two mandates in parliament. However, given the favourable campaign and media agenda (cf. social inequality and the IPCC report), the party did not grow as much as expected. The same disappointment was also apparent among the Greens, which failed to reach the electoral threshold despite receiving increased support (see also discussion below).

All in all, the election turned out to be a small landslide for the left in Norway, which won by a solid majority after eight long years in opposition. As the Labour Party retained its position as the largest party, the Norwegian 2021 election did not reflect the steep trend of declining support for traditional social democratic parties as seen elsewhere in Europe. Nonetheless, the election did indeed show increased fragmentation of the left flank and new and fragile patterns of leftist party cooperation. The growth of a more complex party landscape of medium and small sized left-leaning political parties with various ideological shadings and issue emphases seems to be a trend that could stick well into the future, and is something we observe elsewhere in Europe too.

Erna Solberg’s defeat and the decline of the former government parties

The biggest loser of the election was the Conservative party and the former government parties the Progress Party and the Christian Democrats. The past few years, the Conservative party Høyre had been fiercely criticised from the Left bloc opposition about centralization reforms, tax cuts, and generous spending of the Norwegian oil revenues. Combined with a somewhat limited public enthusiasm towards the government project due to the pandemic as well as the cabinet’s eight years in power, few — if any — were in the end surprised to see the party decline in the 2021 election.

The fall of the Progress Party was also more or less predictable. In the previous election in 2017, their primary issue — immigration — was on top of the Norwegian agenda following the refugee crisis. By 2021, voters no longer considered the issue important, as the pandemic essentially stopped most immigration to Norway.

In addition, the Christian Democratic Party fell below the electoral threshold for the first time since 1936, making the election results even grimmer for the right wing. The Christian Democrats had been ripe with internal conflict over the decision to enter the right-wing cabinet in 2020 while the Progress Party took part in it. Indeed, this conflict eventually led to a party split that probably contributed to the Christian Democrats falling just below the adjustment seats’ electoral threshold. Finally, as mentioned, their party leader was involved in a housing scandal in the middle of the campaign, having obtained free housing from the parliament on questionable grounds. All in all, this contributed to the decline in the Christian Democratic Party’s support from 4,2 to 3,6 percent and a total of 3 mandates (down from 8).

The only right-wing party to perform rather stably was the small Liberal party, which seems to have capitalised on the climate agenda.

Not so green after all? The surprising turn in support for the Green party

Lastly, among the more surprising results, the Green party was not able capitalise on the salience of the climate issue in the election campaign. As mentioned, the UN IPCC Climate Report announced “code red” for humanity in the middle of the campaign, spurring tense political debate about climate and oil issues. One of the world’s largest oil-dependent economies, 20 percent of Norway’s national income comes from oil and gas production and more than 150,000 citizens are employed in the oil and gas sector. The IPCC report therefore not only spurred heated debate about climate change but also the future of Norwegian economy; a debate that more or less dominated the election agenda, including the televised political debates, for a couple of weeks following the report. The Green Party, which entered parliament as late as 2013, rose sharply on the polls and obtained a record 3,000 new members in the period. In these few weeks, polls predicted that the Greens would rise comfortably above the electoral threshold, granting them access to the above-mentioned harmonising seats. However, in the 13th of September, the Greens received 3.96% of the votes, falling a few thousand votes short of the threshold. In contrast to the radical socialist party Rødt, the Greens did not fare too well in rural areas and outside the big cities. Despite some growth in support and their best election so far, the failure to cross the electoral threshold was overall a disappointment for the party.

Government formation

Labour’s preferred majority coalition of the Socialist Left and the Centre party (with whom they governed in 2005-2013) did eventually obtain a majority in parliament. Both the Labour Party and the Socialist Left preferred this three-party coalition, while the Centre Party would rather not have the Socialist Left aboard.

The three parties embarked on government pre-negotiations in September, of which the Socialist Left Party withdrew after a week, citing their disagreement over issues like petroleum and welfare. All three parties had committed to the ambitious goals of the Paris Agreement, slashing emissions by 50-55% by 2030, but disagreed strongly about how to get there.

On the 14th of October, Jonas Gahr Støre therefore became the prime minister of a minority government. Paradoxically, because the Socialist Left left government negotiations, he was not able to capitalize from the landslide election of the left flank after eight years in opposition. Nonetheless, the Labor Party and Centre party cabinet enjoys parliamentary support and cooperates with the Socialist Left in parliament.

Literature

Aardal, B. & Bergh, J. (2018). The 2017 Norwegian election. West European Politics, 41(5), pp. 1208-1216.

Aardal, B. (2011). The Norwegian electoral system and its political consequences. World Political Science, 7(1).

Bergh, J., Haugsgjerd, A., Karlsen, R. (2020). Valg og politikk siden 1945–Velgere, institusjoner og kritiske hendelser i norsk politisk historie. Oslo: Cappelen Damm Akademisk.

Hooghe, L. & Marks, G. (2018). Cleavage theory meets Europe’s crises: Lipset, Rokkan, and the transnational cleavage. Journal of European public policy, 25(1), pp. 109-135.

Lipset, S. M. & Rokkan, S. (1967) Cleavage structures, party systems, and voter alignments: an introduction. In S.M. Lipset and S. Rokkan (eds.), Party Systems and Voter Alignments: Cross-National Perspectives, Toronto: The Free Press, pp. 1–64

Lijphart, A. (2012). Patterns of democracy: Government forms and performance in thirty-six countries. Yale: Yale University Press.

Notes

- The kingdoms of Norway, Sweden and Denmark were united in the Kalmar Union between 1397 and 1523. After the abolishment of the Kalmar union, Norway was ruled as a province of Denmark until 1814, when Denmark was forced to cede Norway to Sweden after its defeat in the Napoleonic wars. Norway then became a independent constitutional monarchy, ruled by the Swedish king in a two-state confederacy until 1905.

- The 19 electoral districts used to overlap with the borders of the administrative counties or regions of Norway (fylker). Due to a major regional reform implemented by the Solberg government in 2020, where the number of administrative counties was reduced to 11, this is however not the case anymore.

- While the Northernmost electoral district Finnmark (75 800 citizens) has five MPs, the capital Oslo (635 000 citizens) has 20 MPs. The seat allocation is conducted by modified Sainte-Laguë method with a first divisor of 1.4.

- At the time of writing this article, we are still awaiting the Norwegian National election survey to arrive; we do therefore not know much about the new Rødt voters’ socio-economic background.

citer l'article

Stine Hesstvedt, Parliamentary elections in Norway, 13 September 2021, Mar 2022, 146-151.

à lire dans cette issue

voir toute la revue