Presidential election in the Czech Republic, 13-14 January 2023

Michal Kubát

Professor of Political Science at Charles University in Prague and the University of West Bohemia (Pilsen)Issue

Issue #4Auteurs

Michal Kubát

Issue 4, January 2024

Elections in Europe: 2023

Introduction

The 2023 Czech presidential election occurred at a time of political tension and societal fatigue caused by the coronavirus pandemic and the war in Ukraine. From a domestic political perspective, the election, which took place approximately one and a half years after the narrow defeat of populist forces in the 2021 parliamentary vote, was characterized by an effort to overcome the discourse which had dominated the mainstream of Czech politics since 2017. The election was also viewed as an opportunity to challenge President Zeman’s political style and direction, while providing the opposition with a platform to voice their discontent with the incumbent government’s policies. It thus raised great concerns and expectations, particularly among pro-democratic and pro-Western segments of society, who saw it as part of a decisive struggle for the Czech Republic’s political future. Despite their limited constitutional powers, Czech presidents have often exercised significant political and social influence, which explains the high level of attention and interest that voters have in presidential elections.

The aim of this text is to bring the reader closer not only to the results of the presidential election, but also to its broader political context. It is is divided into three parts. First, I characterize the institutional role of the Czech president. Next, I discuss the history of presidential elections. Finally, I present the political context of the election and its results.

The Presidency of the Czech Republic: A unique institution

The institution of the Czech presidency is highly specific, with presidents traditionally enjoying an extraordinary position in Czech society and politics. In their institutional role as heads of state, Czech presidents tend to be attributed irrational qualities, a perception which is also common within society and the political class at large. Presidents thus benefit from a quasi-monarchical image as the bearers of universally revered authority. However, they are not ruling presidents with strong powers and their influence is not as much of an executive kind as it is political or even moral.

The reasons for the extraordinary status of the Czech President are historical and cultural. These can be traced back to the times of the Austro-Hungarian Empire, when Francis Joseph I was highly respected in Bohemia. After 1918, the tradition was revisited and developed by the “President-Liberator” Tomáš Garrigue Masaryk and later, to some extent, by the “President-Builder” Edvard Beneš. The presidential institution was so revered and prestigious that even the communists did not abolish it following their February 1948 coup, when they opted against introducing the collective head of state of Soviet-inspired regimes. Czechoslovakia was thus the only European communist country that had a President of the Republic throughout its entire existence. After the fall of communism in 1989, Václav Havel (1989–2003) played a significant role in upholding the tradition of presidential exceptionalism. The subsequent president, Václav Klaus (2003–2013), followed in his footsteps to some extent. However, during the presidency of Václav Klaus, especially in his second term, the prestige of the presidential office began to decline. A controversial general amnesty in 2013 caused significant damage to the institutional reputation of the presidency. Klaus’s successor Miloš Zeman (2013–2023) dealt an even more severe blow to the prestige of the presidency due to his controversial populist political and communication style, which was rejected by a significant portion of society. Moreover, some, though not all, of the Czech electorate opposed Zeman’s pro-Russian positions. The newly elected President Petr Pavel is expected by his voters to restore the traditional seriousness and dignity of the institution. This was one, and perhaps the main, factor that contributed to his election.

A brief history of Czech presidential elections

The 2023 presidential election was only the third direct and general presidential election in Czech history. All previous Czech (and Czechoslovak) presidents were elected by the parliament. From 1918 to 1992, there had been 19 presidential elections in Czechoslovakia. The record office-holder was the first Czechoslovak president Tomáš Garrigue Masaryk, who was elected four times (1918, 1920, 1927 and 1934). Although, according to the Constitution, a person could only be elected for two consecutive terms, Masaryk benefited from an exception to this rule, and could therefore be reelected more than once. The term of office at that time was seven years. The second President was Edvard Beneš, who was first elected in 1935 and successfully ran for re-election in 1946. Meanwhile, after the dissolution of the first Czechoslovak republic, Emil Hácha was elected President (in 1938). He later became the State President of the Protectorate of Bohemia and Moravia (1939–1945).

A similar pattern materialised after the communist coup in 1948. The term of office was still seven years (shortened to 5 years in 1960), and no one could be elected more than twice in a row (in 1960, this restriction was lifted). There were five communist presidents – Klement Gottwald (elected in 1948), Antonín Zápotocký (1953), Antonín Novotný (1957, 1964), Ludvík Svoboda (1968, 1973) and Gustáv Husák, who was elected three times (1975, 1980 and 1985).

After the fall of the communist regime, Václav Havel was elected President in 1989 and subsequently re-elected in 1990. The last Czechoslovak presidential election took place in 1992, but the parliament then failed to elect a new president. In Czechoslovakia, presidents were usually elected unopposed, with the exception of the elections between 1920 and 1935, when Masaryk and Beneš faced a single opponent, and of the 1992 election, contested by 6 candidates. Most of the votes were by secret ballot, except in 1918 (by acclamation), from 1948 to 1964, and in 1989, when public ballot was used instead.

Under the Czech Republic, the parliament elected the president four times. Václav Havel was elected in 1993 and 1998 and Václav Klaus in 2003 and 2008. Direct and general presidential elections were introduced in 2012, with the first direct election taking place in 2013. Miloš Zeman was elected president in 2013 and re-elected in 2018. In both cases, Zeman was elected in the second round of voting, obtaining 54.8% of the vote in 2013 and 51.36% in 2018.

Electoral system

The President of the Czech Republic is elected in a direct and general election by secret ballot for a five-year term of office. Any citizen of the Czech Republic over 40 years of age who is nominated by 20 deputies, 10 senators or 50,000 individual citizens can run for President. A two-round majority electoral system is used. In the first round, any candidate receiving an absolute majority of the vote is elected. If no-one is elected, a second round of voting takes place 14 days later, to which the two most voted candidates of the first-round advance. In the second round, the candidate with the most votes is elected. The second round is held even if only one candidate participates – a situation which has never occurred so far.

As for parliamentary elections, voting traditionally takes place on two days, always on Friday (from 2 to 10pm) and on Saturday (from 8am to 2pm). Voters must vote in person either at regular voting stations or at Czech embassies abroad. There is no possibility of postal voting.

The political context of the election and the election campaign

Eight candidates took part in the 2023 presidential election: MP and former Czech Prime Minister Andrej Babiš (ANO movement, RE), MP Jaroslav Bašta (Freedom and Direct Democracy, SPD, ID), businessman Karel Diviš (ind.), senator Pavel Fischer (ind.), senator Marek Hilšer (ind.), economist and former rector of Mendel University Brno Danuše Nerudová (ind.; the only woman among the candidates), retired general and former Chief of the General Staff of the Army of the Czech Republic and former Chairman of the NATO Military Committee Petr Pavel (ind.) and professor of laboratory medicine and former Rector of Charles University Tomáš Zima (ind.). Pavel Fischer and Marek Hilšer were candidates for the second time, having already run in 2018.

According to the polls, the initial favourites of the election were Andrej Babiš, Danuše Nerudová and Petr Pavel. However, after surpassing the 20% mark early in the campaign, Nerudová’s support gradually waned, and Andrej Babiš and Petr Pavel appeared as the two candidates most likely to advance to the second round of the election – which they eventually did. Danuše Nerudová represented the more liberal segments of society and raised several “progressive” issues in her campaign, such as LGBT rights and sustainable development. Before the second run, Petr Pavel included some of these issues into his campaign in an attempt to expand his voter base.

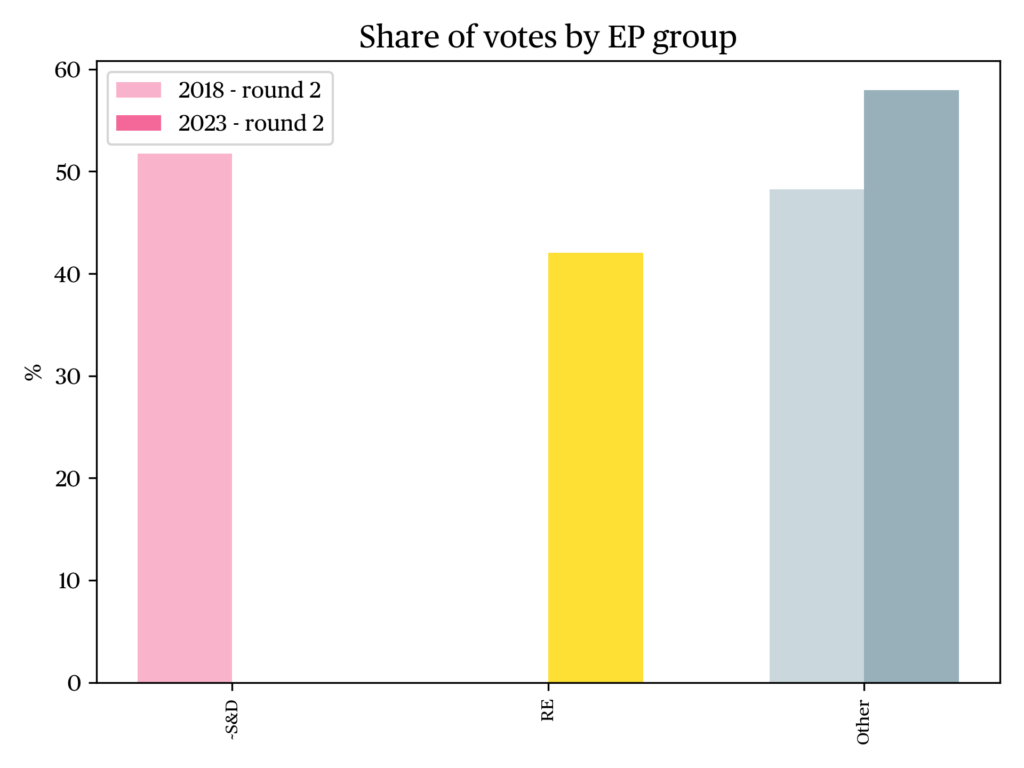

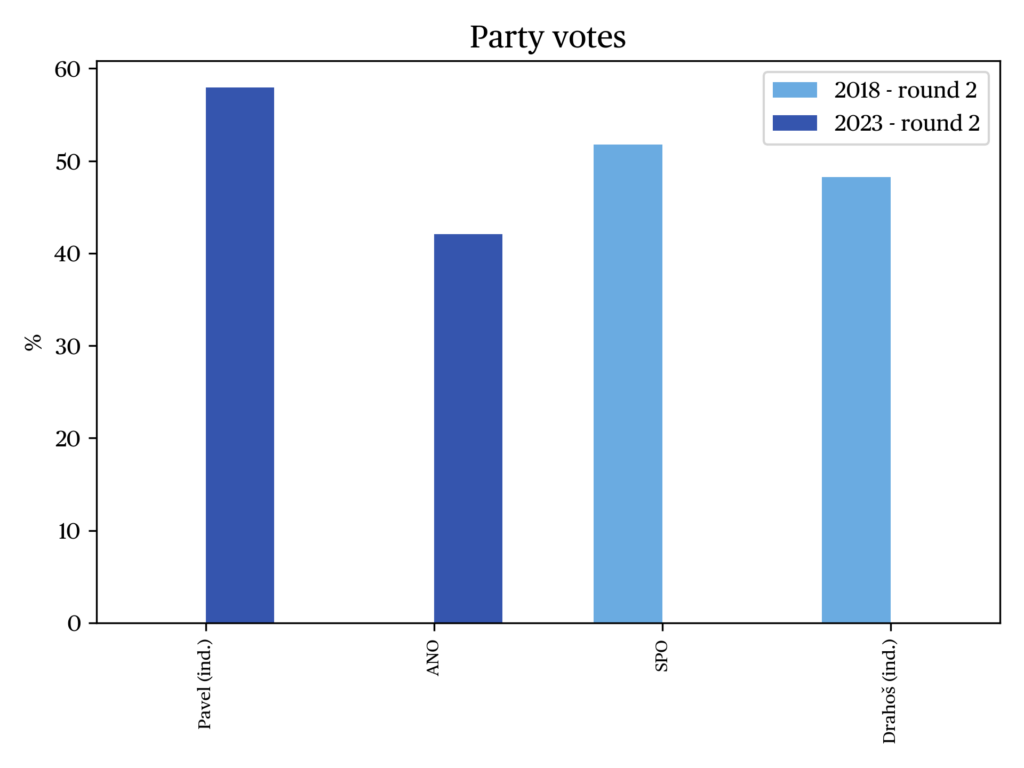

In the second round, two very different personalities stood against each other. Petr Pavel presented himself as a politically moderate, non-populist and pro-Western candidate with a combination of liberal and conservative positions. Before the second round, he was supported by the right-wing SPOLU coalition, which consists of the Civic Democratic Party (ODS, ECR), the Christian Democratic Union – Czechoslovak People’s Party (KDU-ČSL, EPP) and TOP 09 (EPP). He was also supported by the Pirates (Greens/EFA) and the Mayors and Independents (STAN, EPP). These are the government parties that together defeated ANO in the 2021 parliamentary election. Petr Pavel was also supported by a majority of Czech cultural personalities. Between the two rounds of voting, Petr Pavel gained support from those unsuccessful first-round candidates who had campaigned on a pro-democratic, anti-populist platform: Danuše Nerudová, Pavel Fischer and Marek Hilšer. It is worth underlining that Pavel’s candidacy was also publicly endorsed by some well-known ANO members, most notably Ostrava Mayor Tomáš Macura (Ostrava is the third biggest city in the Czech Republic) and Moravia-Silesia Regional Governor Ivo Vondrák.

On the other hand, Andrej Babiš did not give up his populist orientation and rhetoric. In addition to his ANO movement, of which he is the founder, main donor, and chairman, Babiš was also supported by President Miloš Zeman and various extremist left-wing and right-wing forces, including the Communist Party of Bohemia and Moravia (KSČM, GUE/NGL), the Tricolour Citizens’ Movement and implicitly also the extreme right-wing SPD. While not directly endorsing Babiš’s candidacy, SPD leader Tomio Okamura explicitely called his voters not to vote for Pavel.

The political and mental differences between the two main candidates were also evident in their respective electoral campaigns. Petr Pavel ran a relatively moderate campaign, presented himself with the slogan “Let’s restore order and peace to the Czech Republic”, emphasized that he wanted to reconstruct the dignity of the presidential office and did not hide his pro-Western stance. On the other hand, Babiš’s took a much sharper and more aggressive tone. The confrontation escalated before the second round of elections when Babiš aligned himself on Orbán’s “peace” strategy. Using billboards, Babiš tried to create the impression that Pavel, as a retired general and supporter of Ukraine, would drag the Czech Republic into war (the president does not have such power), or that he does not believe in peace. This campaign sparked outrage and was labeled as deceitful, amoral and unethical. As a consequence, Marek Prchal, one of the campaign’s creators, was expelled from the association of advertising professionals Art Directors Club Czech Republic on January 25, 2023.

Results

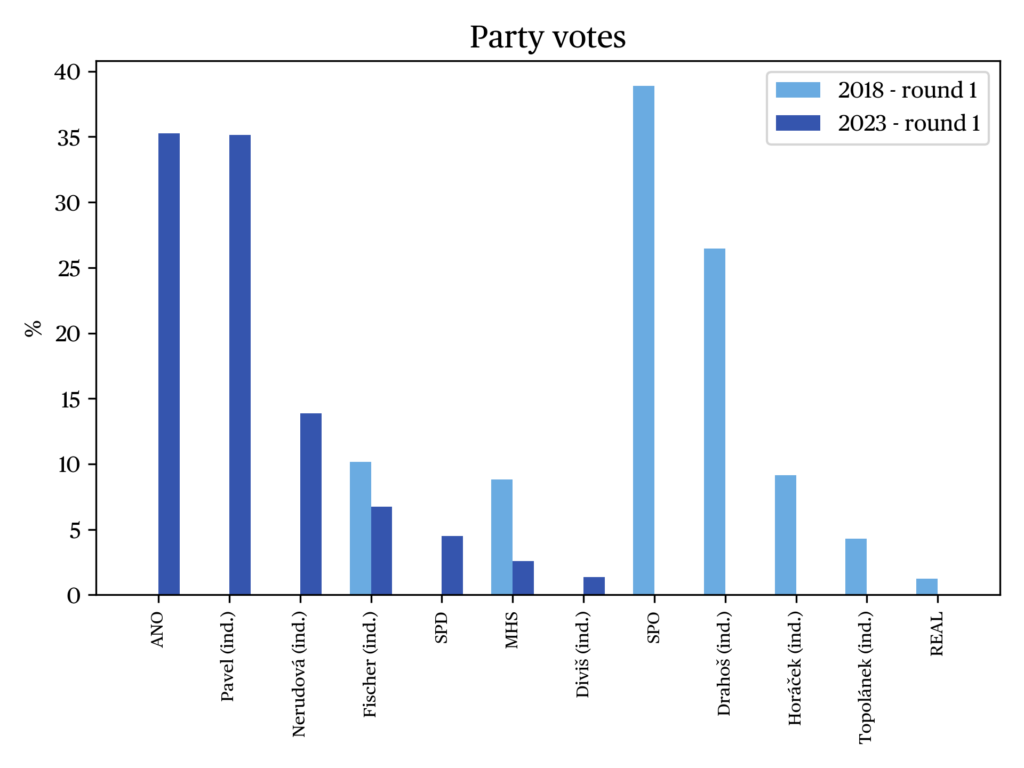

In the first round of elections, no candidate received the majority of votes needed to be elected. Petr Pavel narrowly defeated Andrej Babiš. Danuše Nerudová, once considered a favourite (see above), ended up falling far short of expectations. As had been anticipated by the pollsters, none of the other candidates attracted a significant portion of the electorate. Only one of them – Petr Fischer – obtained more than five percent of the vote.

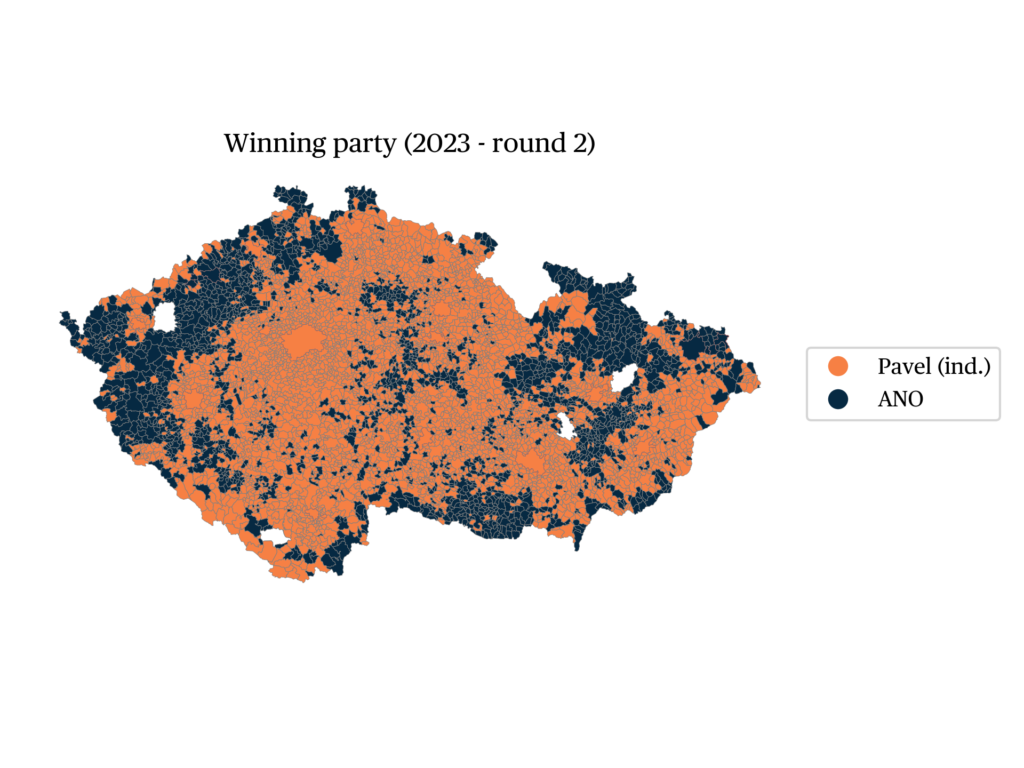

Andrej Babiš and Petr Pavel advanced to the second round of voting, which Pavel won by a large margin, receiving 959,403 more votes than Babiš (Pavel received 3,359,301, Babiš 2,399,898 votes). A closer outcome had been expected.

| Candidate | % Of Votes | |

| 1. Round | 2. Round | |

| Andrej Babiš | 34.99 | 41.67 |

| Jaroslav Bašta | 4.45 | – |

| Karel Diviš | 1.35 | – |

| Pavel Fischer* | 6.75 | – |

| Marek Hilšer** | 2.56 | – |

| Danuše Nerudová | 13.92 | – |

| Petr Pavel | 35.40 | 58.32 |

| Tomáš Zima | 0.55 | – |

* Pavel Fisher received 10.23% in 2018 presidential elections.

** Marek Hilšer received 8.83% in 2018 presidential elections.

Source: https://www.volby.cz

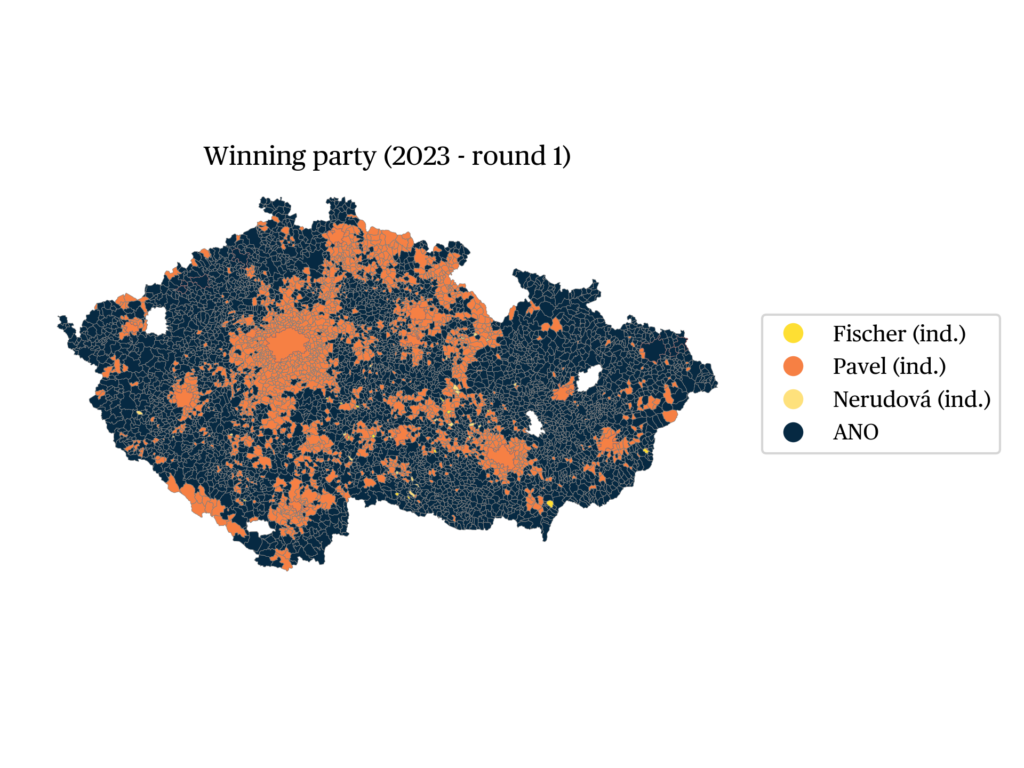

Petr Pavel won in 11 regions (including the capital of Prague), achieving its best results in large cities, while Andrej Babiš placed first in only three regions: Moravia-Silesia, Ústí nad Labem and Karlovy Vary. The regions won by Babiš rank amount the most disadvantaged regions in the Czech Republic in both economical and social terms.

The presidential election was characterized by high voter turnout by Czech standards. Voter turnout was higher than in the previous presidential elections in 2018 and 2013. Notably, there was a higher voter turnout in the second round than in the first round (the same thing happened in the 2018 election). For comparison, voter turnout in the elections to the Chamber of Deputies ranged between 60–65% in the years 2002–2021, with a record of around 75% in the 1990s.

| 2023 | 2018 | 2013 | ||||

| 1. Round | 2. Round | 1. Round | 2. Round | 1. Round | 2. Round | |

| 68.24 | 70.25 | 61.92 | 66.60 | 61.31 | 59.11 | |

Source: https://www.volby.cz

Conclusion

Although the powers of the President under the Czech constitution are limited, the presidential elections hold significant importance in the country’s political landscape. Therefore, they cannot be considered “second-order elections”. Rather, Czech presidential elections are first-order elections, ranking second in importance after the elections to the Chamber of Deputies. Consequently, the public and media interest in these elections is high. This was especially evident in the 2023 presidential election, which generated great expectations. Many voters expressed their desire for change and rejected both the controversies associated with President Miloš Zeman’s term and the populist chaos represented primarily by Andrej Babiš, his ANO party and his political supporters.

The data

First round

Second round

References

Balík, S. et al. (2003). Politický systém českých zemí 1848–1989. Brno: MPÚ MU.

Brunclík M., & Kubát M. (2019). Semi-presidentialism, Parliamentarism and Presidents. Presidential Politics in Central Europe. London and New York: Routledge.

March, M. (2000). Second-Order Elections. In Rose, R. (ed.), International Encyclopedia of Elections (pp. 287–289). Macmillan.

Odvárková, D., & Pohůdka, P. (2023, 23 January). Andrej Babiš kandiduje na prezidenta. Program, názory a priority bývalého premiéra. e15.cz.

Odvárková, D. (2023, 7 January). Danuše Nerudová: Volební program, názory a kandidatura na prezidentku 2023. e15.cz.

Odvárková, D., Sudová, K., & Kanta, A. (2023, 23 January). Generál Petr Pavel: Program, názory a kandidatura na prezidenta 2023. e15.cz.

iRozhlas (2023, 1 February). Od roku 2026 by se mohlo volit jen jeden den. Vláda schválila novelu zákona. iRozhlas.

Trousilová, A. (2023, 26 January). Marketéři vyloučili ze svých řad Prchala. Novinky.cz.

Parliament of the Czech Republic. Historie parlamentarismu a české ústavnosti. Online.

Hromková, D., & Dohnalová, A. (2023, 18 January). Stojíme za Babišem, tvrdí ANO. Vondrák a Macura ale nejsou jediní, kdo volí Pavla. Aktuálně.cz.

citer l'article

Michal Kubát, Presidential election in the Czech Republic, 13-14 January 2023, Nov 2023,

à lire dans cette issue

voir toute la revue