Regional election in Castilla-La Mancha, 28 May 2023

Josu Mezo

Lecturer in Sociology at the University of Castilla-La ManchaIssue

Issue #4Auteurs

Josu Mezo

Numéro 4, Janvier 2024

Élections en Europe : 2023

Introduction

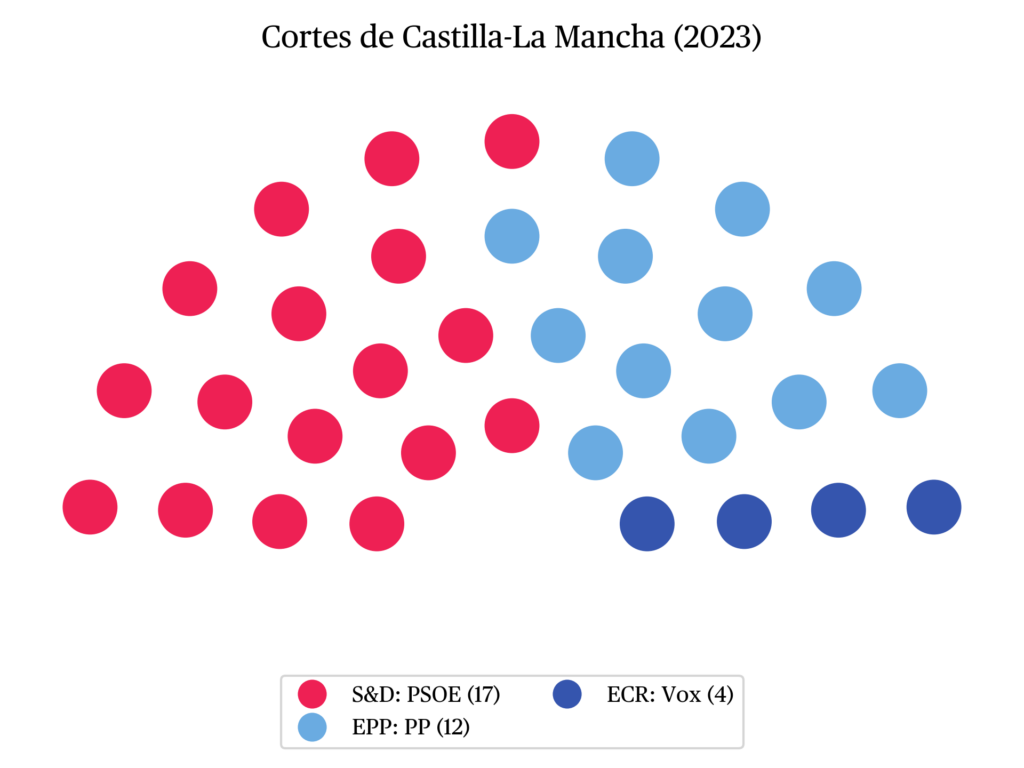

The elections to the Cortes, the regional parliament of Castilla-La Mancha, were held on May 28, 2023, with the governing centre-left Spanish Socialist Workers’ Party (PSOE) managing to maintain, by the narrowest of margins (17 out of 33 seats), the absolute majority it enjoyed since 2019. Two right-wing parties, the moderate Popular Party (PP) and the far-right Vox party, which were expected to form a government alliance, if the numbers added up, were left in opposition, with 12 and 4 seats, respectively. Meanwhile, that same day, Spaniards chose all local councils and the parliaments of 11 other regions. The results were largely favorable to the PP and Vox, while the PSOE and its government partners faced negative outcomes.

Castilla-La Mancha is a sparsely populated region (2.1 million spread over 79,500 km2) to the South of Madrid, with 58% of the population living in towns below 20,000 inhabitants (vs 32% in Spain as a whole), and a strong rural character. It is also a relatively poor region.

Its politics were bipartisan until 2011, with the PSOE and the PP winning more than 80% of the vote, and the vast majority or all the seats in the Cortes. Since 2015, as in the rest of Spain, new parties won a sizable percentage of the vote: 19% in 2015 and 25% in 2019 (Mezo 2019). However, after an electoral law reform in 2014 the size of the Cortes was reduced to 33 deputies, elected in five electoral districts (the five provinces of the region), which choose between 5 and 9 deputies each. Thus, the electoral system is technically proportional (closed list voting with the D’Hondt distribution rule, and a legal minimum threshold of 3%), but clearly favors the big parties, and has left several of the new parties, with up to 8.6% of the vote, out of Parliament (Fernández Esquer 2016 and 2020).

National political context

In Spain, regional elections are often highly influenced by national political dynamics. National debates irremediably infiltrate local and regional politics and make it difficult for public discussion to focus on the specific problems of each region. This is particularly clear in the current period of strong political polarization (Torcal and Comellas 2022; Torcal 2023). The imperfect two-party political system of Spain gave way in 2015 to a period of instability that has not yet ended, with the birth, rise and disappearance of a centrist party (Ciudadanos), the lightning rise, crisis and reconfiguration of a coalition of far-left parties (called Podemos, then Unidas Podemos, and most recently Sumar), and the success of a far-right party (Vox). In practice, we are now in a two-bloc system with PP plus Vox, on the right, and PSOE plus Podemos/Sumar, on the left, in which radical voices have more weight and visibility than in the past. The two blocs collide not only along the right-left axis, but also on the centre-periphery axis, dealing with the demands for self-government, particularly in the Basque Country and Catalonia. Broadly, the right has been more centralist, reluctant to transfer powers to the autonomies, and wary of the efforts to promote the language and identity of the regions or nationalities. The PSOE, and even more the parties and coalitions to its left, have been much more open to decentralization, and more comprehensive or even active promoters of nationalist policies to favour regional languages and identities. This overlapping of the left-right and centre-periphery conflicts has intensified ever since the PSOE leader, Pedro Sánchez, was elected Prime Minister in 2018 with the votes of the Basque and Catalan nationalist parties. These included EH Bildu, heir of the parties allied to the terrorist group ETA (active until 2011, responsible for some 900 deaths and more than 6,000 injuries), as well as the Catalan parties that in 2017 had promoted an illegal independence referendum in Catalonia, and had even made a pseudo proclamation of the Catalan Republic, which led to a major constitutional crisis, the temporary suspension of self-government in Catalonia, the flight abroad of several members of the Catalan government, and the prosecution and imprisonment of many others. After the 2019 elections, Sánchez was elected president again, in January 2020, this time without the positive vote of those parties, which have nevertheless been sought after and used to approve budgets or other important laws. The accumulation of the effects of the 2008-2011 economic crisis, the political conflict in Catalonia, the pandemic, and the control measures to fight it, and the inflationary period after the war in Ukraine have created a situation of intense political polarization between the blocs that support and oppose the Sánchez government.

The electoral campaign

Only three parties were expected to get into the Cortes in the 2023 elections. On the one hand, the PSOE, whose candidate, Emiliano García-Page, had been the president of the region since 2015 (between 2015 and 2019 in coalition with Podemos, since 2019 with an absolute majority). On the other hand, the right-wing bloc featured the PP, led by Paco Núñez, who had already been a candidate in 2019, and Vox, led by David Moreno, the party’s spokesperson in the Talavera de la Reina city council. The polls predicted a very tight dispute for the majority between the PSOE and the combination of PP and Vox, which were widely expected to govern together if they had enough seats.

As expected, national politics topics pervaded the communication strategies of the political parties. The PP, especially, paired the pictures of its candidate with those of the president of the national party, and the regional presidents of Madrid and Andalusia, the first and third most populated in the country, both governed by the PP, and proposed as examples of the type of policies that Castilla-La Mancha would need. On the other hand, the youth organization of the PP, put out campaign materials with photographs of President García-Page and Arnaldo Otegi, a leader of the Basque nationalist party EH Bildu, who had spent time in jail as a collaborator with ETA. This denigration by association was vehemently denounced by the Socialist candidate. The link is particularly dubious because García-Page, belongs to the wing of the PSOE that is critical of the alliances that, out of necessity or conviction, the PSOE has made with Basque and Catalan nationalist parties. In fact, President García-Page, like his predecessors, habitually boasts, and often did so during the campaign, of his autonomy from the national party, which contrasts with the alleged obedience of other parties to directives coming from Madrid. In this sense, water policy, and in particular the criticism of the Tajo-Segura water transfer, was used by García-Page as an epitome of his defense of the interests of the region (“If one day I defend the transfer, you can call me traitor or bastard”), in contrast to the position of the PP (shared with Vox), which defends the transfer as part of a water policy that takes into account the interests of all regions of Spain. This contrast is frequently used by the PSOE to present itself as the only party that really defends the interests of the region, when they conflict with those of other parts of Spain.

More generally, policies related to the agricultural and livestock sectors appeared often in the discourse of the three main parties. Above all, PP and Vox appealed to the vote of rural areas, harshly criticizing the Socialist government’s policy in relation to limitations on irrigation, the lack of control of rabbit pests, a recent Family Farming law that includes the possibility of expropriating little-exploited land, the scarcity of aid against drought, or the poor treatment of the hunting sector.

No issue of purely regional politics dominated the campaign. The three parties launched proposals, with little detail, on improvements in the management of public services (health and education, assistance to dependent people, nursing homes), although typically it was the PSOE who insisted more on these social issues. The PP complemented these with calls for lowering almost all taxes regulated by the region, and in particular taxes on inheritances and donations, that other communities governed by the PP have practically eliminated (between close relatives), regardless of the value of the inheritance or gift.

Results

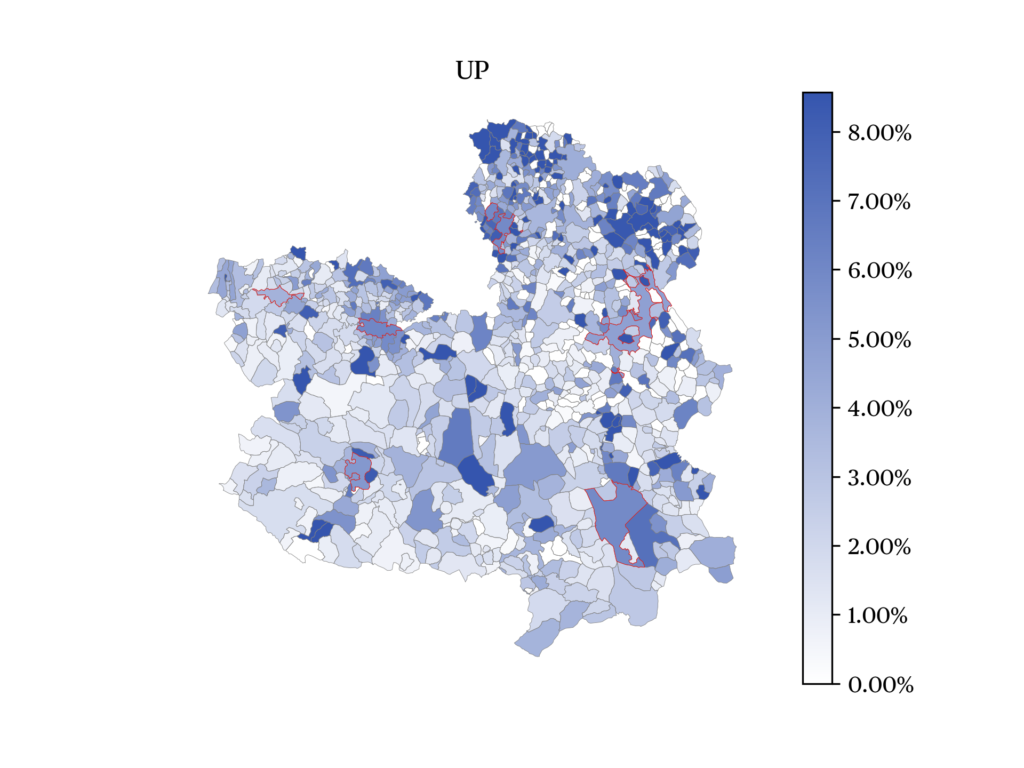

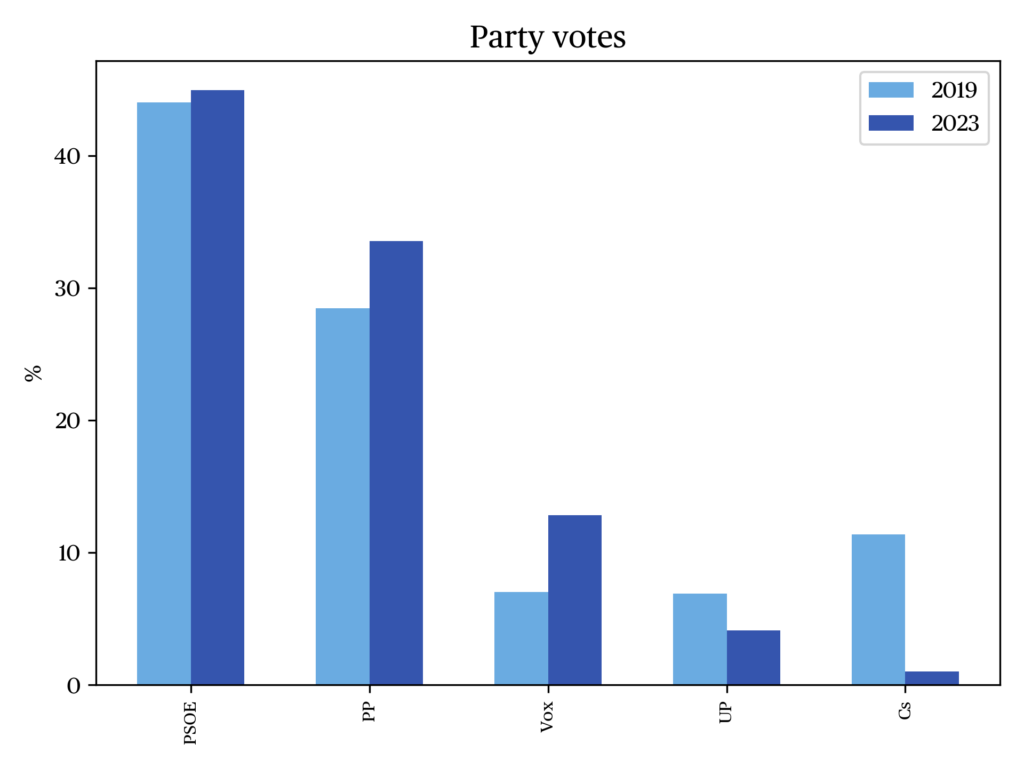

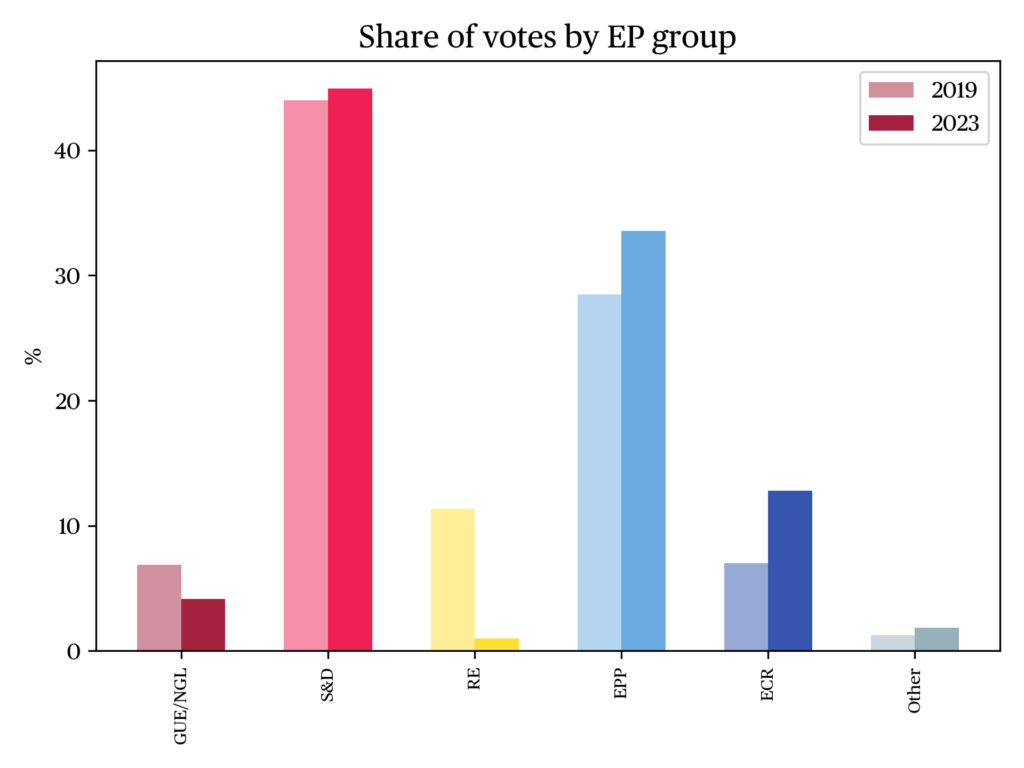

As the polls predicted, the election results were ultimately very close. The PSOE obtained 45.1% of the votes and 17 seats (44.1% and 19 seats in 2019), which gave it a single seat majority (see “the data”). On the other hand, in comparative terms, the victory of the PSOE was quite exceptional: on the same day the PSOE and its partners lost the majority in seven of the ten communities where they were in power. The Socialists’ result in Castilla-La Mancha is by far the best obtained by the PSOE in any region in the most recent electoral cycle (2020-2023) with an unweighted average of 27.0%, and Extremadura a distant second with 38.8%. And so, Castilla-La Mancha, with its 2.1 million inhabitants, has become the most populous region with a Socialist president, and the only one where the party enjoys a majority in parliament. The other left-wing party, Unidas Podemos, to the left of the PSOE, had a very modest result, 4.1% (6.9% in 2019) and remained out of the Cortes.

The right-wing bloc saw an important reconfiguration. First, like everywhere else, the centrist Ciudadanos imploded, going from 11.4% of the votes and 4 seats to 1% of the vote, and no deputies. On the contrary, the PP improved its results to 33.7% and 12 seats (from 28.5% and 10). Finally, Vox jumped from 0 to 4 seats, as its share of votes rose from 7% to 12.8%, in line with its results elsewhere.

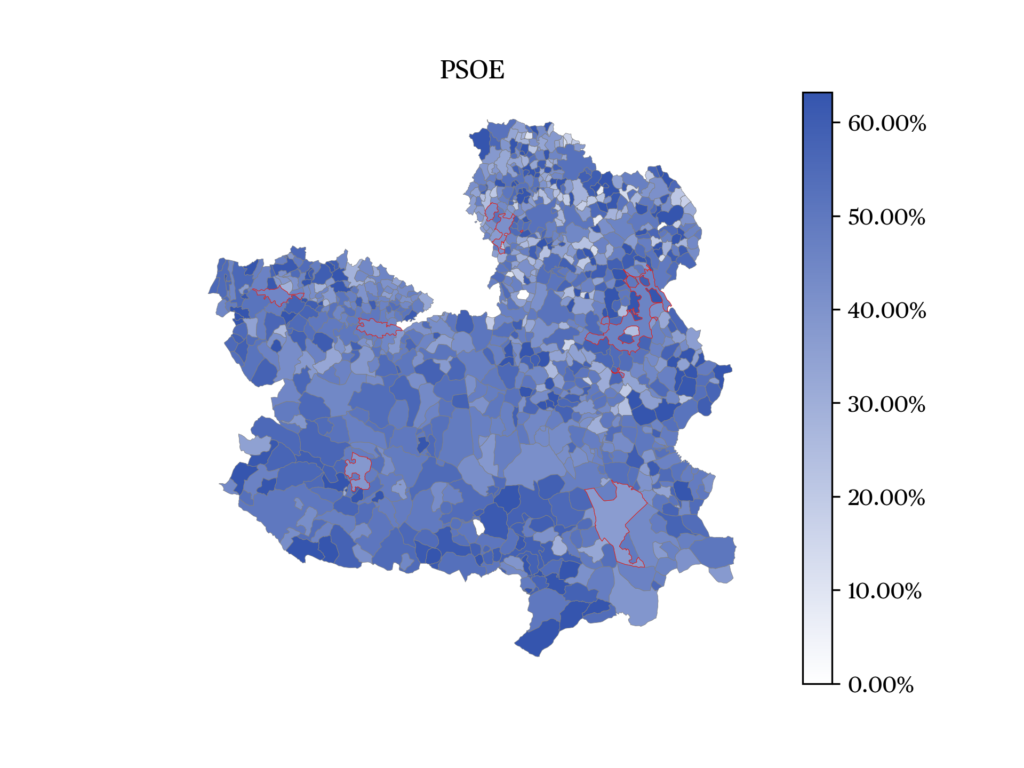

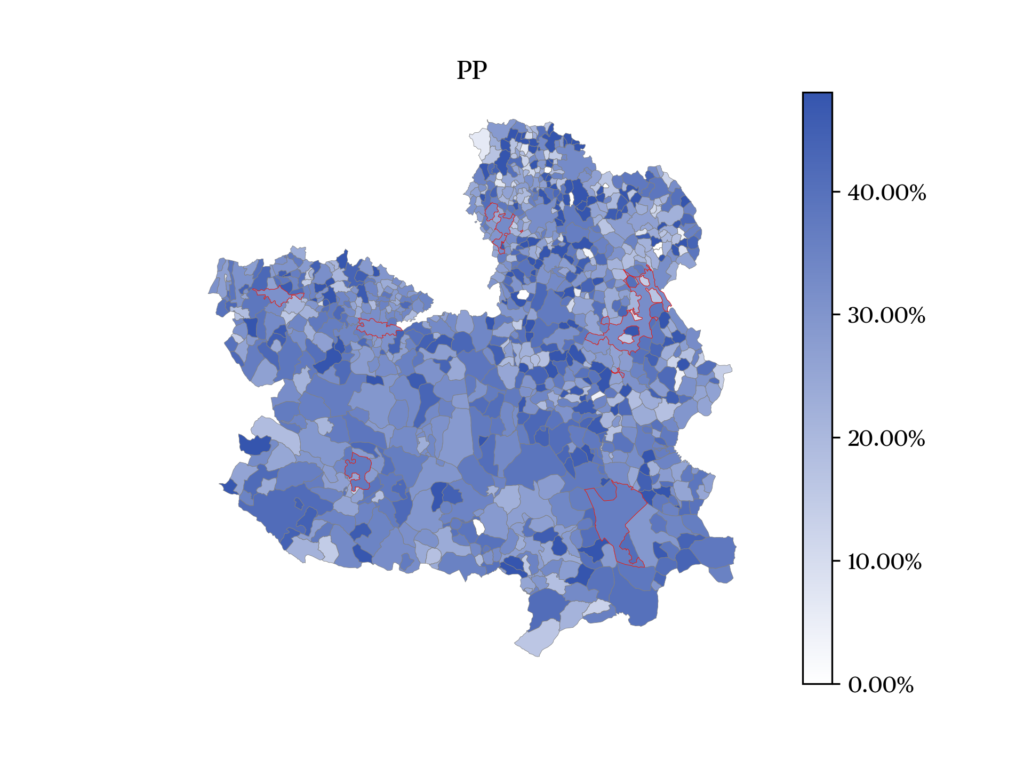

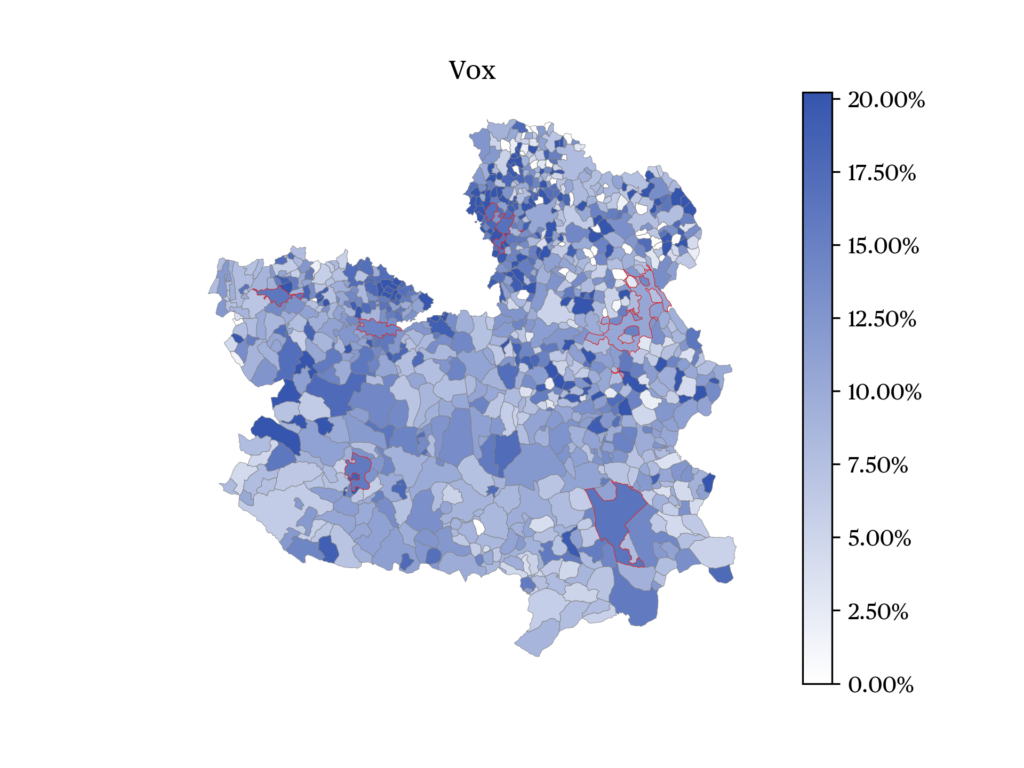

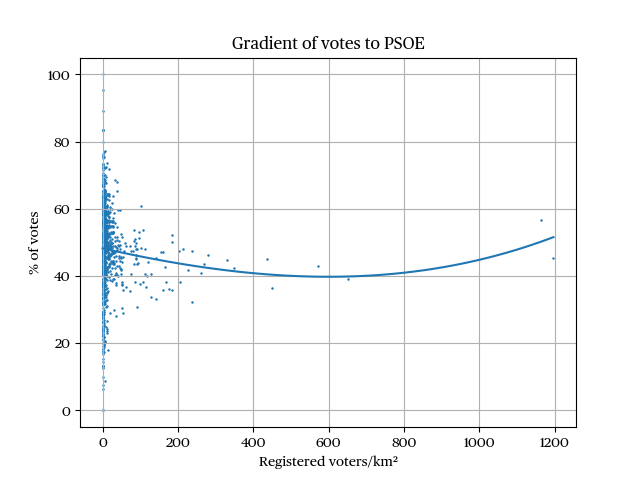

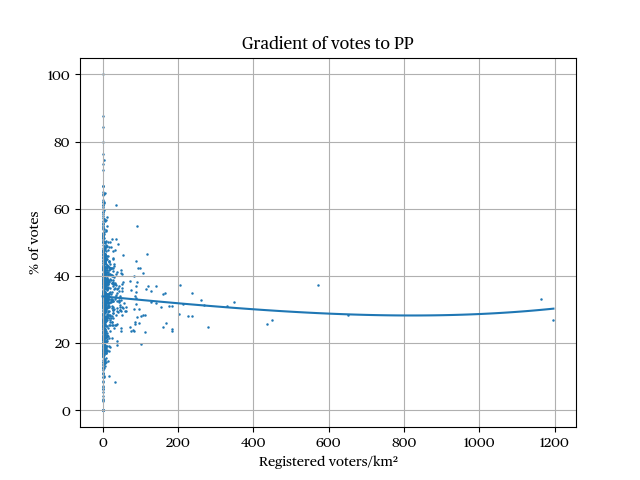

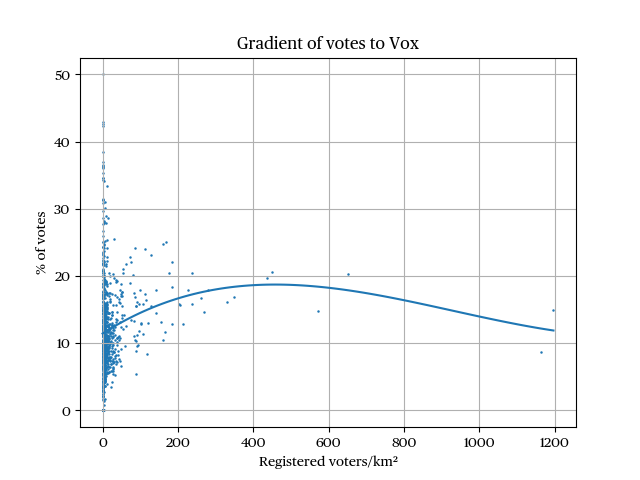

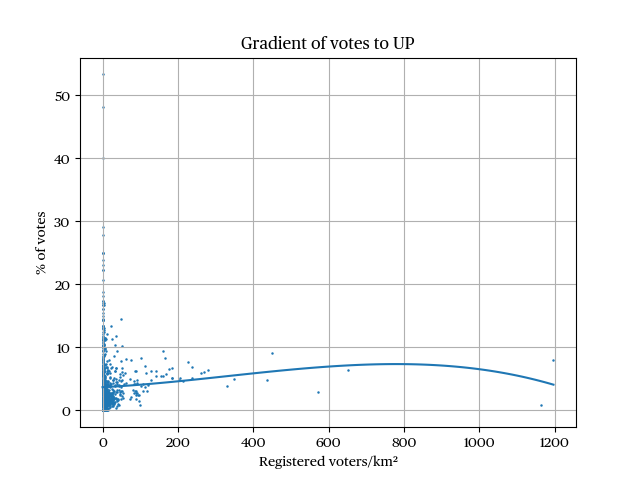

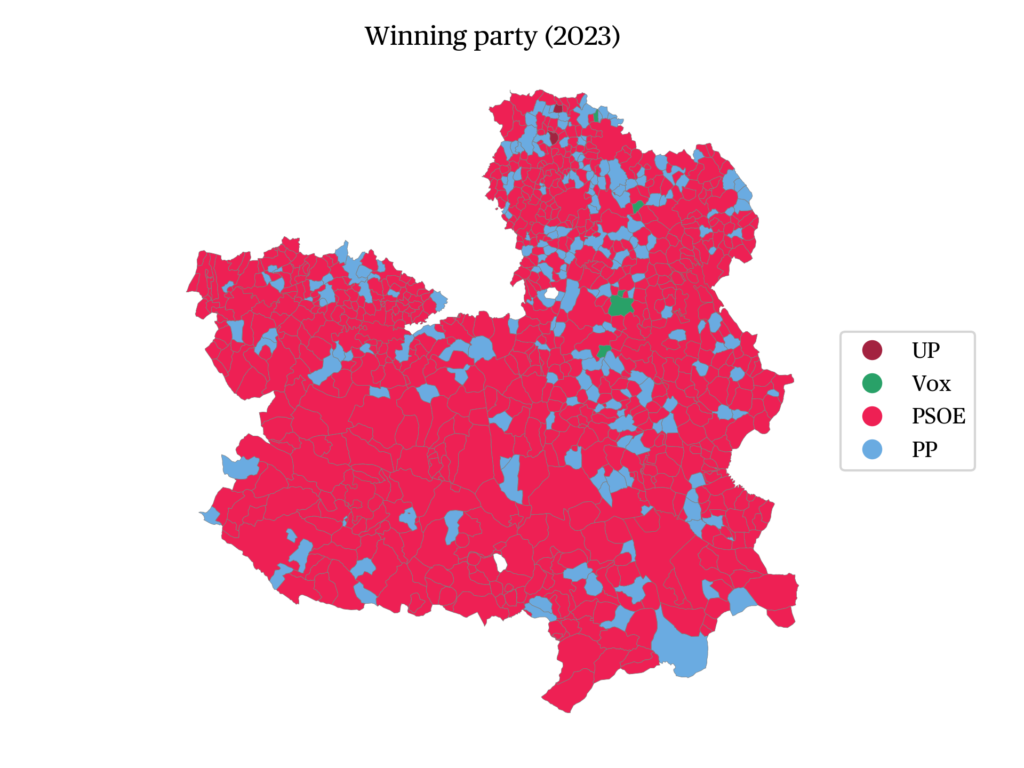

The geographic analysis of the vote does not show clear patterns. The Socialists won in most municipalities (see “the data”), and the five provinces, with a vote range from 42.2% to 47.4%. The PP fluctuated between 30.3% and 35.5% and Vox between 10.5% and 16.1%. There is no clear geographic pattern of party votes (Figure a), nor along the rural and urban divide, with hardly any correlation between the party vote and the population of municipalities. Equally population density shows no noteworthy relationship with the success of the different parties (Figure b). If anything, despite the appeals of the PP and Vox to the rural vote, it is the PSOE which obtains the best results in the smallest towns. To see this, we can group municipalities with similar size into three blocs with a comparable number of total voters (up to 4,000 registered voters, from 4,000 to 20,000 and more than 20,000). The PSOE has a clearly decreasing percentage of votes in them (48.4%, 45.5% and 41.1% respectively), while the vote for the PP barely changes, and both Vox and Unidas Podemos have a slightly higher vote in the most populated municipalities.

Analysis

The most striking aspect of the election results is that, in an unfavourable national context, the PSOE slightly increased its percentage of the vote, already comparatively high, and maintained its absolute majority in the Cortes. This happened in a region that is slightly more conservative than the national average (in the CIS post-election survey (CIS 2023b), for example, on a scale from left (1) to right (10), the Spanish average was 4.7 and that of Castilla-La Mancha was 5.0).

The success of the PSOE then consists in keeping its broad appeal for very wide ideological sectors. Thus, in the aforementioned survey, the PSOE had a declared vote of 64% among the most left-wing voters (1 to 3 on a scale of 1 to 10), 60% among the centre-left (positions 4 and 5) and 22% among the centre-right (positions 6 and 7). The corresponding percentages in the 12 autonomies that voted that day were 36%, 28% and 7%. So, the PSOE is once again the hegemonic party of the left, leaving Unidas Podemos with a residual vote. This is possibly influenced by the electoral system, which especially since the last reform, favors strategic voting, making it almost impossible for a party with less than 10% of the vote to obtain seats.

Importantly, the PSOE also attracts a fifth of centre-right voters. This is probably related to the “regionalist” position of the party in Castilla-La Mancha, especially in relation to water management and the Tagus-Segura water transfer, and its “Spanish nationalist” messages regarding the alliances of the PSOE with nationalist parties in the national parliament. Additionally, in other regions, and in the national government, the far-left allies of the PSOE have championed policies on issues like gender equality, LGTBQ+ rights, or climate change, which right-wing parties have rejected as wrong or excessive, and have targeted in their campaigns. Meanwhile, in Castilla-La Mancha, the PSOE has governed alone, muting the chances of that kind of criticism. This suits well with García-Page’s folksy style, including old-fashioned comments on gender issues, which surely contribute to his success among conservative voters. In fact, in the CIS pre-election survey (CIS 2023a), García-Page was one of only two Socialist presidents who received a pass (5.1 points in a 1-10 scale), from centre-right and right-wing voters (positions 6 to 10 on the ideology scale).

The same factors that explain the success of the PSOE can be used to account for the narrow failure of the PP and Vox to reach the majority. Their campaign slogans were probably too much focused on criticisms of the national PSOE and its leader Pedro Sánchez, its leftist or socially progressive policies, and its allegedly borderline treacherous alliances with separatist parties. But those arguments rung hollow in the context of Castilla-La Mancha. Additionally, the PSOE was protected from the appeal of other parties to the rural vote by its long-standing position against the Tagus Segura water transfer, and its actual organizational presence, established decades ago, across the region.

To sum up, the regional elections in Castilla-La Mancha are a testament to the capacity of the regional branch of the PSOE, and its leader, to carve a distinct profile that isolates them from national trends, and form a majority government in a conservative region that only two months later, in the general election of July 23rd gave a clear majority of its votes to rightwing parties, and in particular gave a five point lead to the PP over the PSOE (39% to 34.1%).

The data

References

CIS (2023a). Estudio 3402 Preelectoral Elecciones Municipales y Autonómicas 2023. Online.

CIS (2023b). Estudio 3410 | Barómetro de junio 2023. Postelectoral Elecciones Municipales y Autonómicas 2023. Online.

Fernández Esquer, C. (2016). La reforma del sistema electoral de Castilla-La Mancha de 2014. Cuadernos Manuel Giménez Abad, 11: 76-85.

Fernández Esquer, C. (2020). El Sistema Electoral De Castilla-La Mancha Tras La Reforma De 2014: Análisis de sus Rendimientos y Propuestas De Mejora. Parlamento y Constitución. Anuario, 21: 11-38.

Mezo, J. (2019). Castilla-La Mancha: competición unidimensional y bipartidista por el centro, rota por la crisis. In En busca del poder territorial: cuatro décadas de elecciones autonómicas en España (pp. 211-234). Madrid: Centro de Investigaciones Sociológicas (CIS).

Torcal, M. (2023). De votantes a hooligans: La polarización política en España. Madrid: Catarata.

Torcal, M. & Comellas, J. M. (2022). Affective Polarisation in Times of Political Instability and Conflict. Spain from a Comparative Perspective. South European Society and Politics 27(1): 1-26.

citer l'article

Josu Mezo, Regional election in Castilla-La Mancha, 28 May 2023, Jun 2024,

à lire dans cette issue

voir toute la revue