Regional election in Mecklenburg-Vorpommern, 26 September 2021

Issue

Issue #2Auteurs

Erik Baltz , Sophie Suda , Maximilian Andorff-Woller

21x29,7cm - 167 pages Issue 2, March 2021 24,00€

Elections in Europe : June 2021 – November 2021

Situation before the election

The election for the 8th state parliament of Mecklenburg-Vorpommern took place on 26 September 2021, at the same time as the Bundestag election and the election for the Chamber of Deputies in Berlin. In contrast to the other two elections of the election year 2021, however, this Landtag election was held under clear auspices. From the beginning, the favourite for the office of Minister-President was the incumbent Manuela Schwesig (SPD, S&D). She was elected in 2017 after her predecessor Erwin Sellering (SPD, S&D) resigned for reasons of health. Since Schwesig came into office without a mandate of her own, her leadership now had to be legitimised electorally. Her previous government was based on a red-black majority in the state parliament consisting of the Social Democratic Party of Germany (SPD, S&D) and the Christian Democratic Union of Germany (CDU, EPP). In terms of substance, her coalition partner could only accomplish very little, so the SPD set the tone in government with a strong focus on Schwesig. This was also reflected in the polls, in which government satisfaction among SPD supporters was almost 20 percentage points higher than among CDU supporters (Infratest dimap 2021).

Nevertheless, in the election campaign the SPD focused less on content and more on top candidate Schwesig — for example, campaign material such as the “Manu Magazin” was distributed to households. The other parties had little to counter this strongly personalised strategy. The CDU with its top candidate Michael Sack (CDU, EPP) was hardly convincing. Sack had taken over the leadership of the party in 2020 after Philipp Amthor (CDU, EPP) — who was originally intended for the party chair — had disqualified himself for this post following allegations of corruption. Moreover, the SPD seemed to have little to attack on the substantive level, as the CDU had always supported the government’s actions, and Sack was also unable to match Schwesig’s sympathy ratings on the personal level (Forschungsgruppe Wahlen 2021).

The largest opposition party Alternative for Germany (AfD, ID) was hardly visible in the election campaign, which was also due to the fact that their top candidate Nikolaus Kramer (AfD, ID) had to spend a long time in hospital for medical reasons (ibid.). Moreover, Schwesig’s policies were well received in the country. With the abolition of contributions for road construction and fees for day-care facilities, Schwesig had won over many voters, and her rigorous, statesmanlike behaviour during the Coronavirus pandemic had also had a positive effect on her approval ratings. With her temporary representation of the SPD chair at the federal level — together with Malu Dreyer (SPD, S&D) and Thorsten Schäfer-Gümbel (SPD, S&D) – she also showed that Mecklenburg-Vorpommern is led by a politician who is well connected and competent in federal politics. At the same time, the SPD’s upswing in polls at the federal level provided a strong tailwind for the state SPD, with state polls also predicting a clear victory for the Social Democrats.

Results of the election

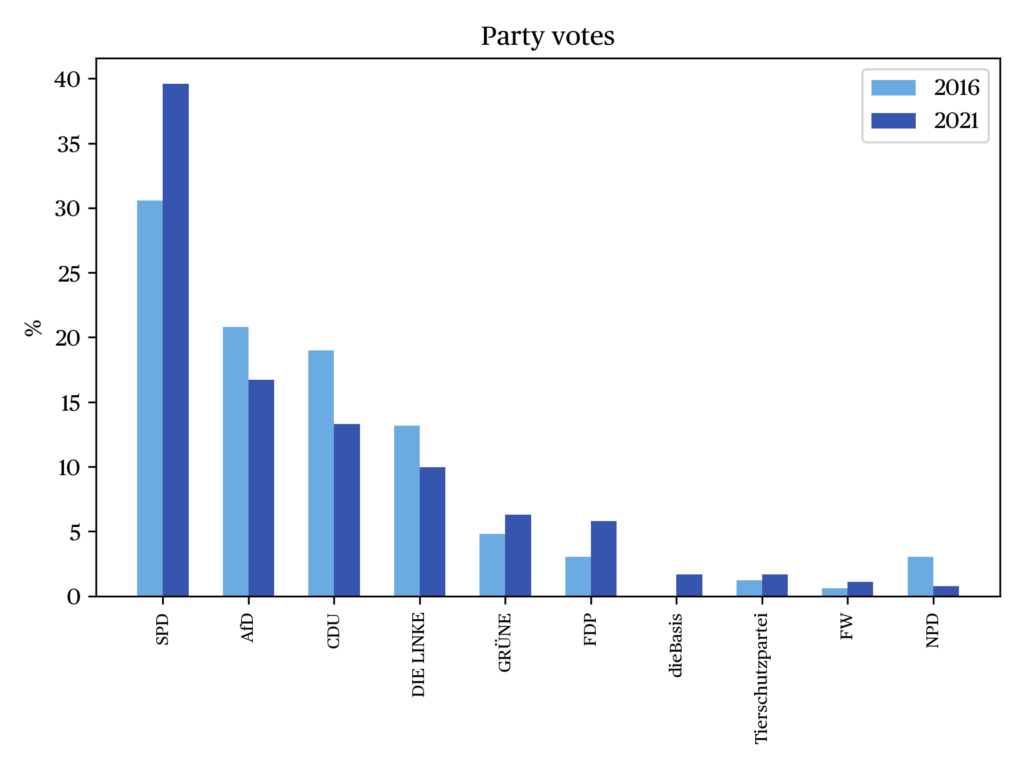

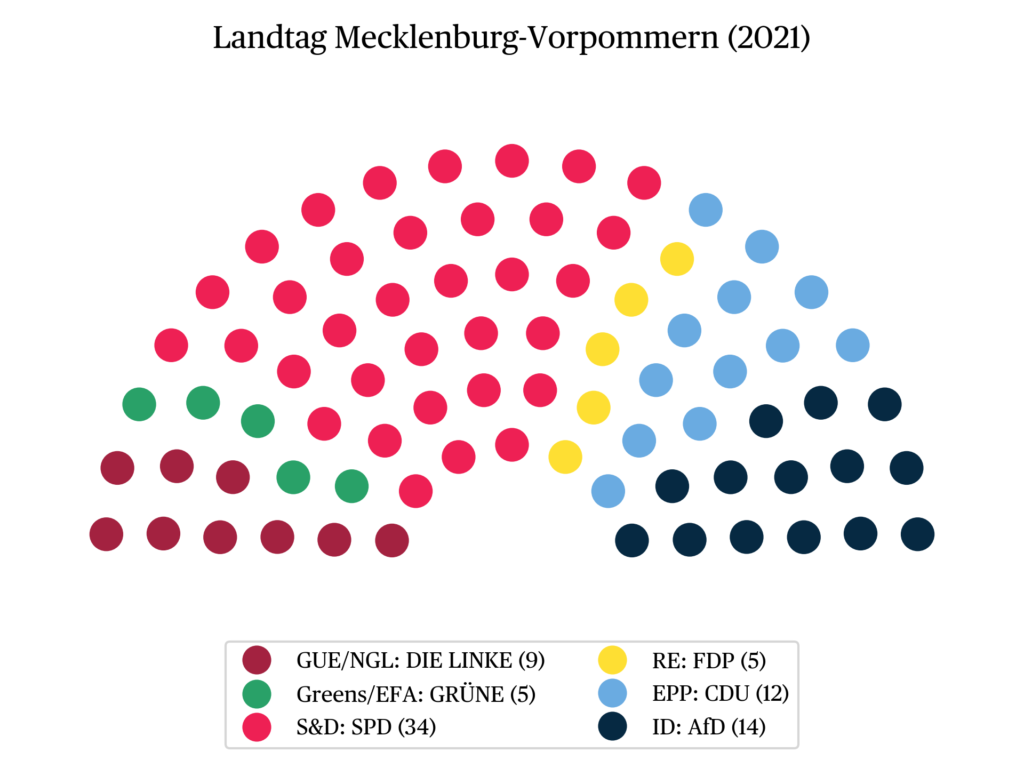

The evening of the election produced the expected victory for the SPD. With just under 40% of the second votes, the SPD increased its share of the vote by almost a third, while all other parties represented in the parliament suffered losses (see chart). The AfD — once more the second largest party — lost 4.1 percentage points, while the CDU even received 5.7 percentage points less of the vote. Party leader Sack then resigned from the party chair, creating a power vacuum within the party. As a result, a leading contact person was missing in the subsequent exploratory talks with the SPD, which can be seen as a determinant for the failure of the continuation of the coalition. The share of the vote of the fourth parliamentary party, Die Linke (The Left, GUE/NGL), also fell by 3.3 percentage points. At the same time, the parties Bündnis90/Die Grünen (Greens, G-EFA) and Freie Demokratische Partei (FDP, RE) succeeded in entering parliament – both had still failed to clear the 5% threshold in 2016. The newly formed parliament is thus programmatically more diverse and characterised by a plurality of interests that has long been the status quo at the federal level and in some state parliaments.

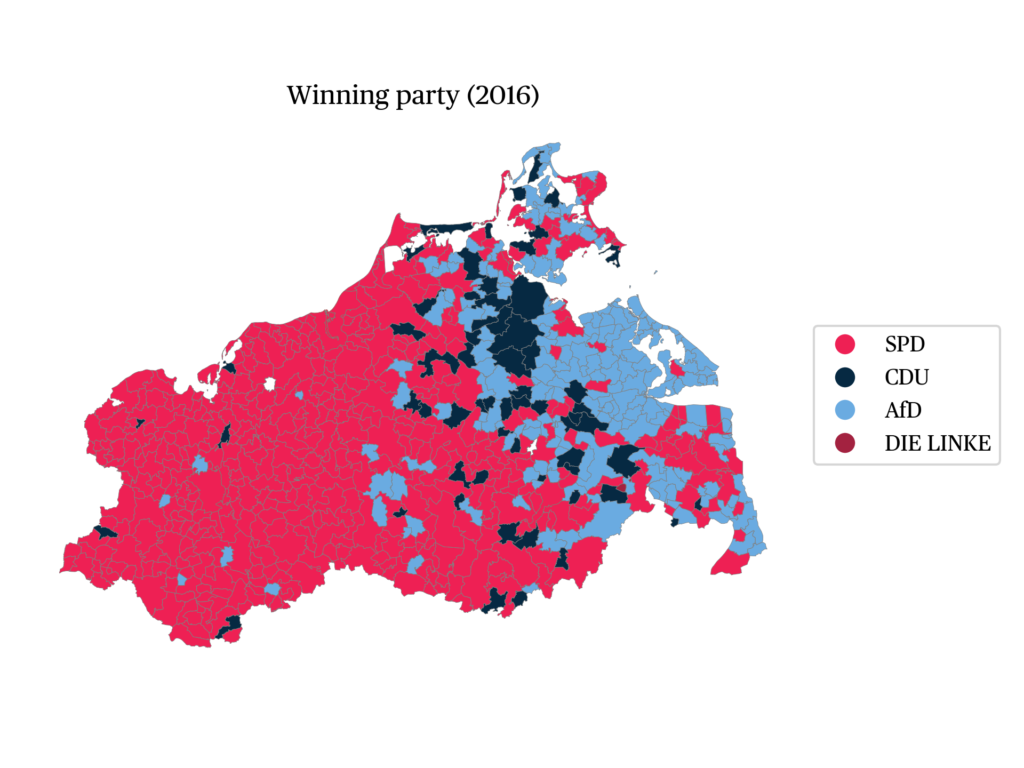

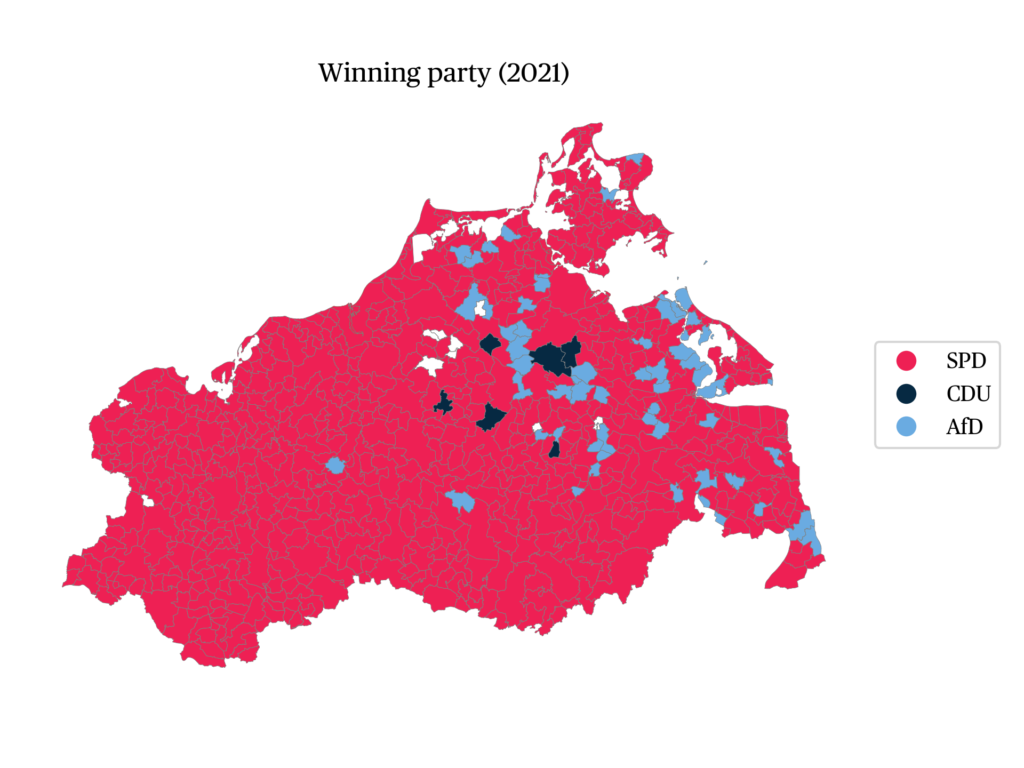

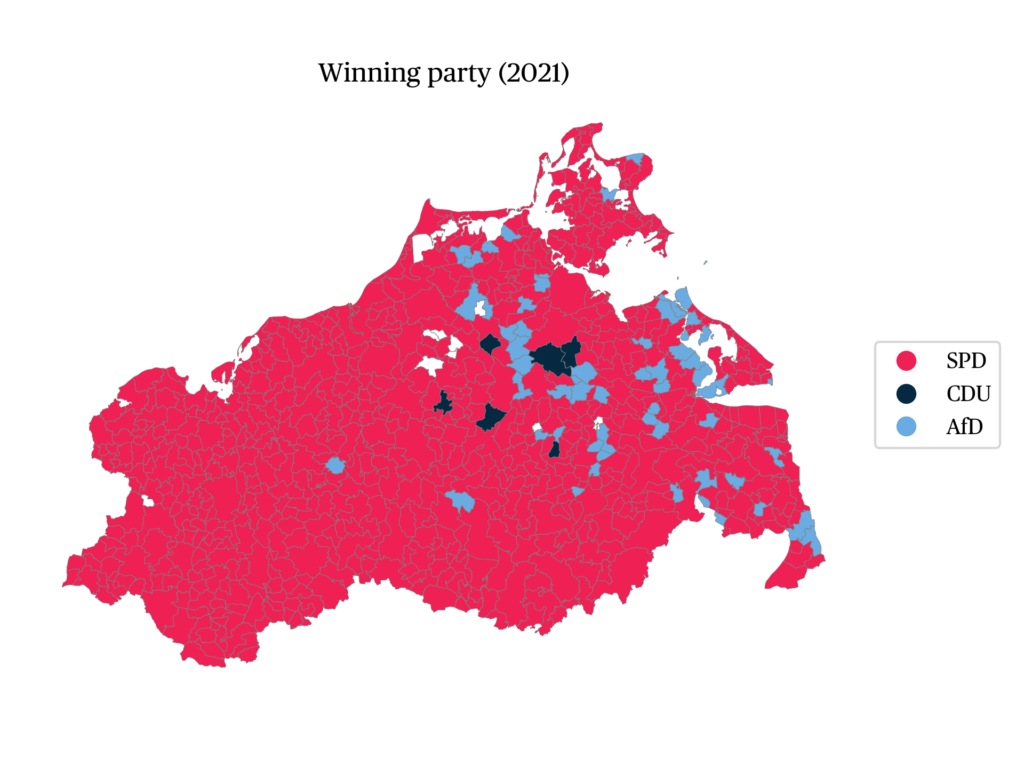

The election results in Mecklenburg-Vorpommern reflect the nationwide trend with clear victories for the SPD, Greens and FDP and significant losses for the CDU, AfD and Left. The great success of the SPD was also reflected in the results at constituency level. Whereas in 2016 a clear east-west divide could be observed in the state, whereby the SPD clearly dominated the western and central parts of the state, but in the east had to cede many constituencies to the CDU and AfD, in 2021 the SPD dominated in almost all parts of the state (see chart).

CDU and AfD did continue to win in some constituencies, but the victories were fewer and less concentrated. The constituencies won by AfD are almost exclusively located in the eastern part of the state. Smaller parties, for their part, did not create surprises. The Animal Protection Party got 1.7% of the vote, well below the 5% threshold for entering the parliament. The Querdenker movement, which emerged during the COVID pandemic as a civil society counterweight to the state machinery, ran in the elections under the name of Grassroots Democratic Party of Germany (dieBasis), but only obtained 1.7% of the vote as well. The National Democratic Party (NPD) also declined from the 2016 state election, and only won 0.8% of the vote.

Turnout increased by 9 percentage points, from 61.7% to 70.8%, which represented the third-highest turnout in the history of the state. An important reason for this success may be the public satisfaction with the government’s work. While in 2016, discontent was particularly strong in the eastern parts of the state, in 2021 the government paid particular attention to these constituencies. In this light, it is hardly surprising that satisfaction with the government evolved almost in parallel with SPD’s electoral success. Despite the increasing satisfaction with the government, CDU, a partner in the outgoing coalition, did not manage to increase its share of the vote.

Transnational political trends

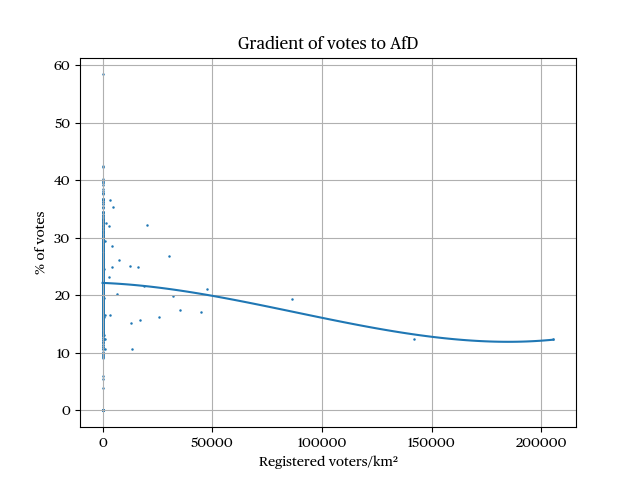

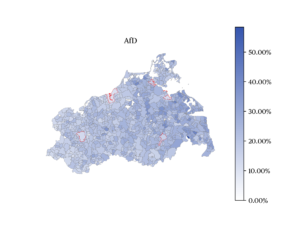

The results of the votes of the SPD, AfD and Linke in the state elections in Mecklenburg-Western Pomerania were significantly higher than in the federal elections which took place at the same time. In the case of the AfD and the Left, this difference can be attributed, among other things, to differences between the “new” East German and the “old” West German federal states. Parties that are assumed to be close to the former German Democratic Republic (GDR) and Russia continue to perform better in the eastern German states than in western German states (Arzheimer 2021). The AfD also managed to win a particularly large number of votes in the eastern constituencies near the Polish border (see chat b).

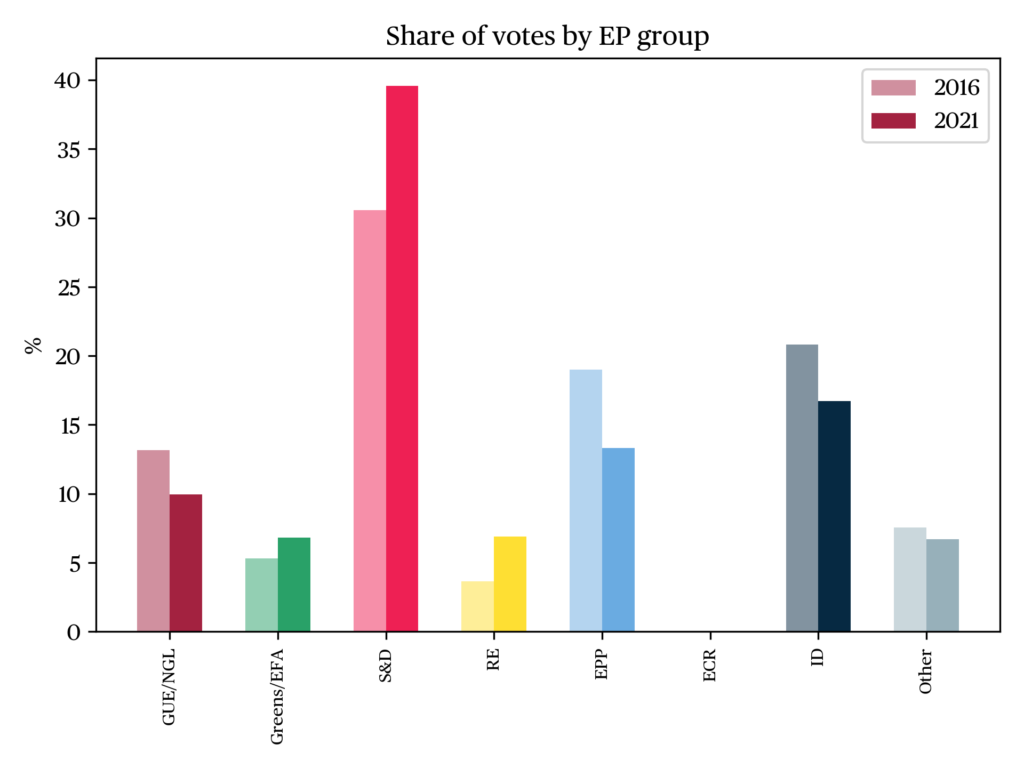

The above-average result of the SPD in Mecklenburg-Western Pomerania is also striking, both in comparison to other state elections and the election to the European Parliament. The SPD’s share of the vote in the state election is among the highest in the parliaments of the German states and is, as it were, significantly higher than the share of the vote for the Progressive Alliance of Social Democrats in the election to the European Parliament (S&D) and is also among the highest in the parliaments of the German states. Whether the state result can be explained by the strengthening of the SPD at the federal level, or whether the success at the federal level was favoured by the strong state SPD, is unclear. In terms of the second-order election theory, the influence of the federal level on the state level is stronger than vice versa (Müller & Debus 2012). In this case, however, possible synergy effects through the stronger integration of the state party into federal politics – for example, in the figure of Schwesig – also seem plausible.

Socio-demographic trends

The state’s ageing population and low population density make it more difficult for some parties to establish themselves. With 69 inhabitants per square kilometre, the state of Mecklenburg-Vorpommern is the most sparsely populated state in Germany and has lost a considerable amount of population since reunification (Destatis Datenreport 2021). Even though the birth low from the 1990s and early 2000s has been overcome by now and immigration figures have exceeded emigration figures since 2017 (Statistisches Amt MV), the population continues to decline due to the ageing of the state’s population and currently stands at 1.6 million. In 2019, Mecklenburg-Vorpommern was last in terms of average gross earnings and third last in terms of disposable income of private households. In September 2020, the unemployment rate was only 6.9%, but a west-east divide can be seen in the state, with the west of the state at 5% and the east at almost 10% (Destatis Datenreport 2021).

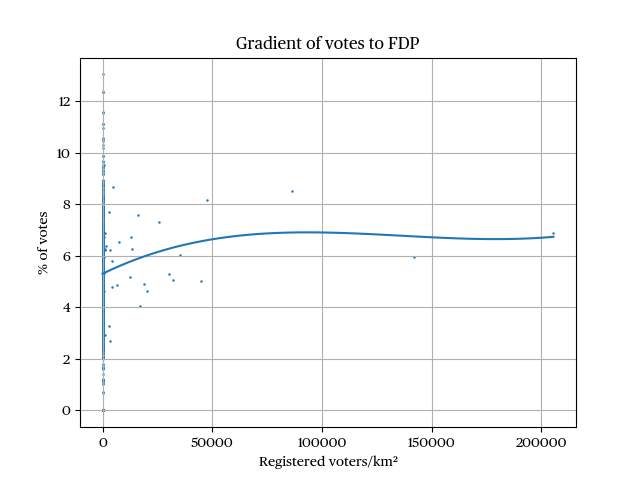

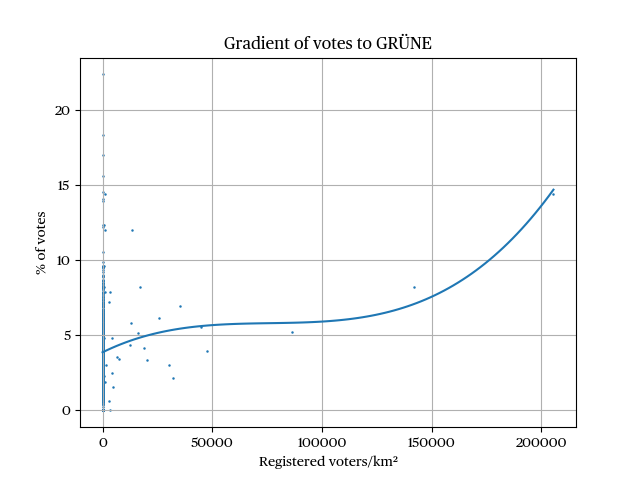

The Greens in particular, and to a lesser extent the FDP, are primarily elected in the larger cities (see chart c). In addition, however, the core electorate of both parties is hardly represented in Mecklenburg-Vorpommern. The Greens, who are mainly elected by citizens in big cities with above-average incomes, find it difficult to represent their ideas for environmental policies in rural areas. The FDP relies mainly on the self-employed, who are also difficult to find in Mecklenburg-Vorpommern, the state with the third lowest number of businesses (MV Statista Dossier 2021). Both the Greens and the FDP represent different progressive directions and are therefore supported particularly by young people. This can also lead to both parties competing for these small voter potentials, which further explains their poor performance in comparison to the federal level. Both parties were not represented in the previous state parliament and, with 6.3 and 5.8 percent respectively, form the two smallest parliamentary factions in the coming legislative period with only five seats each.

One party that benefits from the demographic trends is the AfD, which often achieves strong results in sparsely populated, economically underdeveloped regions with a high average age (Franz et al. 2018). This does not necessarily mean that the oldest population group votes for this party; rather, it is due to the often perceived lack of prospects and the feeling of being forgotten and abandoned by established parties, that people in such areas become susceptible to populist and nationalist opinions and parties (Dellenbaugh-Losse et al. 2021). As can be seen in the illustration above, the AfD’s main voter groups are located in sparsely populated areas, which supports this theory.

It is also interesting that the AfD scores most strongly in the 30-45 age group, i.e., a group that was born in the GDR but only lived through it for a few more years. This means that although this group no longer grew up socialised by a dictatorship, they actively experienced the rural exodus and the social and economic problems of the 1990s and are therefore potentially susceptible to positions that contradict established policies.

Geographic differences and dynamics

Especially in the 2016 state election, clear differences between the west of the state, dominated by the SPD, and the east, from which the AfD emerged as the election winner, can be seen. In 2021, the AfD’s strongholds continue to be in the east, but their number has declined sharply and been cut by the SPD. How did this happen?

In the fields of economic development, average income, unemployment rate and infrastructure, strong differences between the western and eastern parts of the state can be seen, with the east always occupying the weaker position. The direct border with Poland in the east of the state may also have a positive influence on the AfD’s vote. Jäckle et al. (2018) explain this by arguing that right-wing populist and xenophobic attitudes can easily become entrenched due to an atmosphere of economic competition and cross-border crime, which may lead to a general strengthening of the AfD in German border areas. However, a single-cause explanation does not suffice. Other reasons for the AfD’s decline could be the declining national trend, internal disputes in the state party or a lack of interest in the issue of refugees among the population. However, it should not be ignored that after its own poor performance in 2016, the state government and especially the SPD actively tried to win back voters in the east of the state and to involve Vorpommern more in state politics. As Franz et al. (2018) suggest, greater attention should be paid to economically underdeveloped regions. The state government did this primarily through the Vorpommern Strategy, according to which a Parliamentary State Secretary for the Vorpommern part of the state (Patrick Dahlemann, SPD, S&D) was appointed, who had the power to invest almost 3 million euros annually in regional projects and schemes from a development fund opened specifically for this purpose. In addition, the newly created office was to give the people in the region the feeling that they could transport their concerns more directly and easily to the state capital of Schwerin. Whether the money, the direct contact or federal political trends had a direct influence is debatable; in any event, it can be observed that the AfD suffered considerable losses in almost all constituencies and especially in the eastern part of the state.

Coalitions

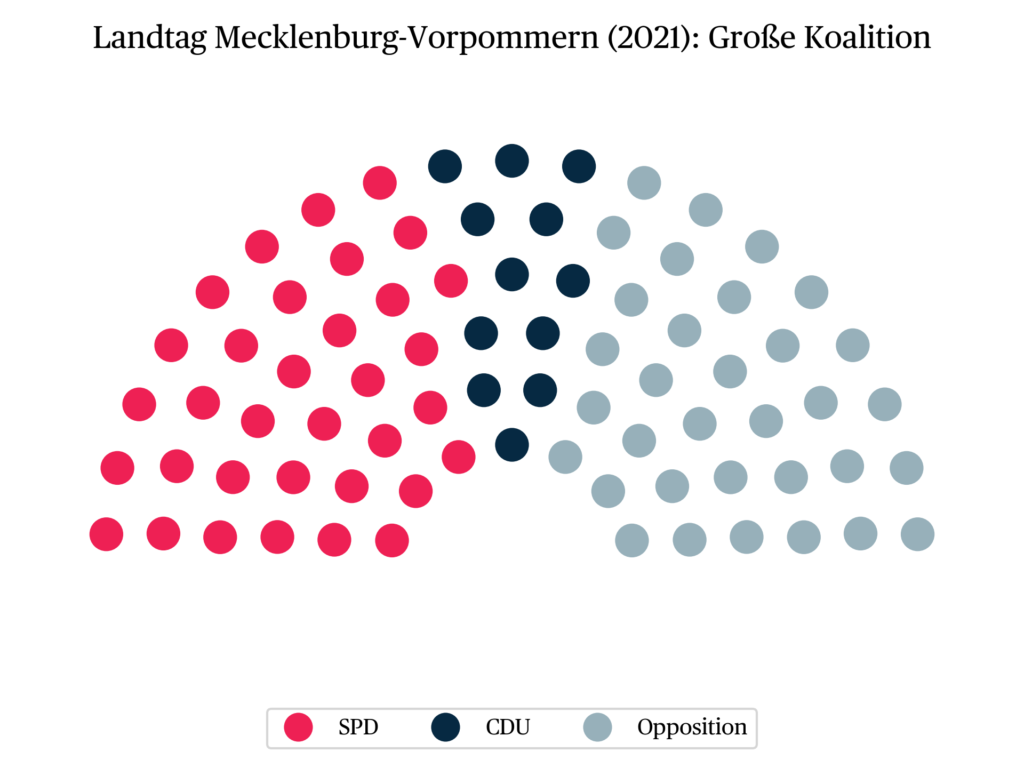

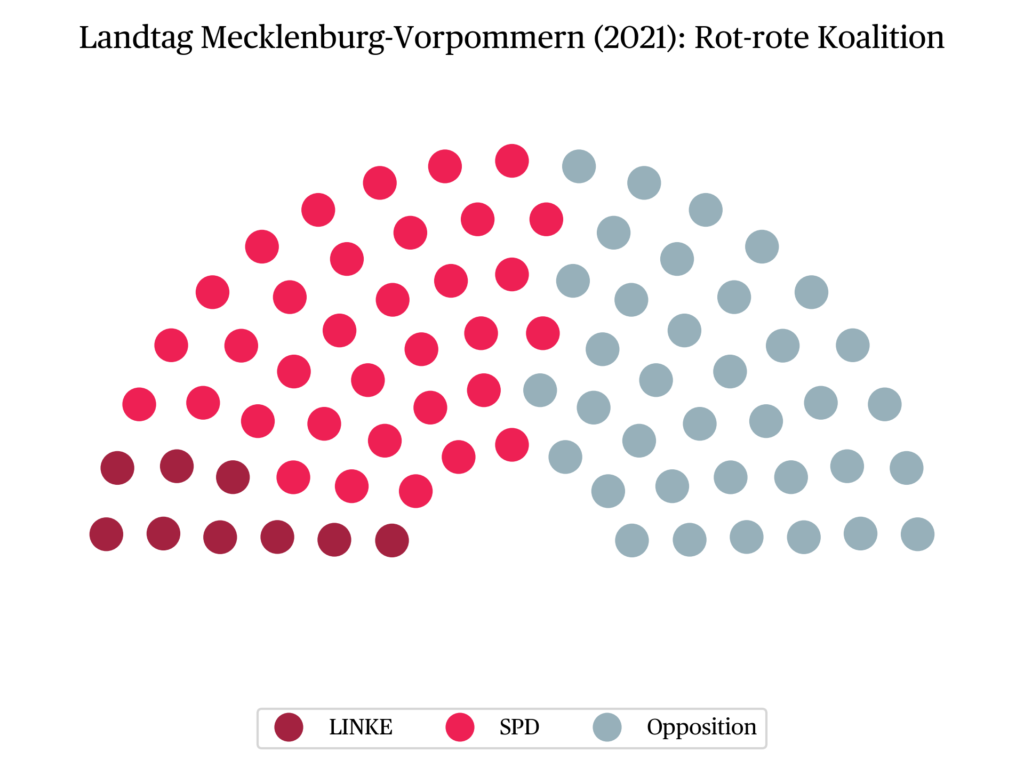

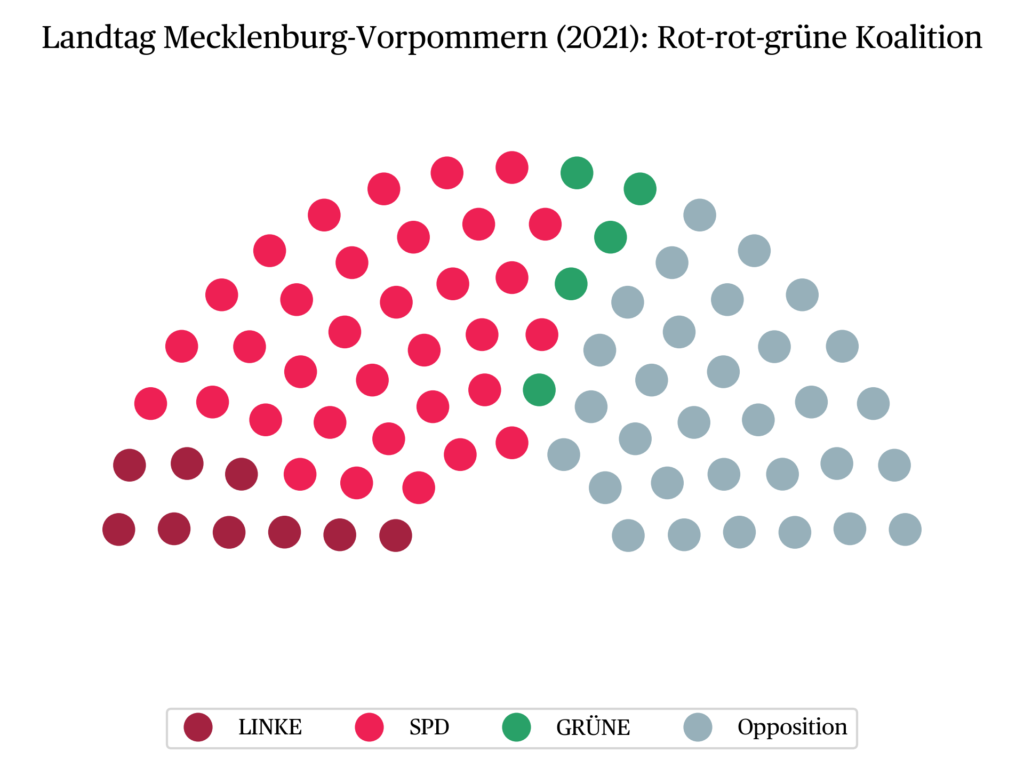

After the state elections, the SPD and the Left Party agreed to start coalition negotiations. In the run-up to the election, three different coalitions were considered mathematically possible and politically feasible: a continuation of the ” Grand Coalition” between the SPD and the CDU, an alliance between the SPD and the Left and a ” Traffic Light Coalition” consisting of the SPD, the FDP and the Greens. The SPD held exploratory talks with all parties represented in the state parliament, with the exception of the AfD. However, a tripartite alliance between SPD, FDP and Greens was assessed as unlikely, as the two potential junior partners are new to the state parliament and the state parties have little parliamentary and government experience. Two weeks after the election, Manuela Schwesig announced that the SPD would negotiate a coalition with the Left Party. The reason given for starting coalition talks was the large substantive overlap between the parties, for example in education policy, state development and social infrastructure. Some of the central points in the coalition negotiations are the creation of new teaching positions, the introduction of free after-school care, the lowering of the voting age in state elections to 16 and the promotion of an increase in the minimum wage to twelve euros. This will be the first time since 2006 that the CDU is not part of the government in Mecklenburg-Western Pomerania. The Left Party, on the other hand, will be able to form a coalition with the SPD again after 15 years in the opposition. Between 1998 and 2006, the Party of Democratic Socialism (PDS), the precursor of the Left, had already formed a coalition with the SPD. This red-red coalition under Minister-President Harald Ringstorff (SPD) was the first coalition between the two parties on the state level in Germany. The renewed alliance between the two parties can be interpreted as a “shift to the left” in state politics. A coalition between the SPD and the Left would have a comfortable majority in the 79-member parliament with 43 seats (see chart d). Regardless of the outcome of the coalition talks, a future coalition partner of the SPD will certainly have to shift its focus from the prime minister to its own substantive priorities.

Literature

Arzheimer, K. (2021). Regionalvertretungswechsel von links nach rechts? Die Wahl der Alternative für Deutschland und der Linkspartei in Ost-West-Perspektive. In Weßels, B. & Schoen, H. (eds.): Wahlen und Wähler — Analysen aus Anlass der Bundestagswahl 2017, Springer.

Dellenbaugh-Losse, M., Homeyer, J., Leser, J, & Pates, R. (2021). Toxische Orte? Faktoren regionaler Anfälligkeit für völkischen Nationalismus. Rechtes Denken, rechte Räume?. transcript-Verlag, pp. 47-82.

Destatis Datenreport (2021). Online.

Franz, C., Fratzscher, M. & Kritikos, A. S. (2018). AfD in dünn besiedelten Räumen mit Überalterungsproblemen stärker. diw Wochenbericht 85.8, pp. 135-144.

Forschungsgruppe Wahlen e.V. (2021). Wahlen Mecklenburg-Vorpommern 2021. Online.

Infratest dimap (2021). Mecklenburg-VorpommernTREND Mai 2021. Online.

Jäckle, S., Wagschal, U. & Kattler, A. Distanz zur Grenze als Indikator für den Erfolg der AfD bei der Bundestagswahl 2017 in Bayern? Zeitschrift für Vergleichende Politikwissenschaft 12.3, pp. 539-566.

Müller, J. & Debus, M. (2012). Second order- Effekte und Determinanten der individuellen Wahlentscheidung bei Landtagswahlen: Eine Analyse des Wahlverhaltens im deutschen Mehrebenensystem. Zeitschrift für Vergleichende Politikwissenschaft 6.1, pp. 17-47.

Ostsee-Zeitung (2016). Dahlemann – der „Kümmerer vor Ort“. Ostsee-Zeitung. Online.

Statistisches Amt Mecklenburg-Vorpommern (2021). Gesellschaft und Bevölkerung. Online.

Vorpommern Fonds (2021). Online.

citer l'article

Erik Baltz, Sophie Suda, Maximilian Andorff-Woller, Regional election in Mecklenburg-Vorpommern, 26 September 2021, Mar 2022, 111-116.

à lire dans cette issue

voir toute la revue