Regional election in Saxony, 1 September 2024

Marianne Kneuer

Professor at TU DresdenIssue

Issue #5Auteurs

Marianne Kneuer

Issue 5, January 2025

Elections in Europe: 2024

Background

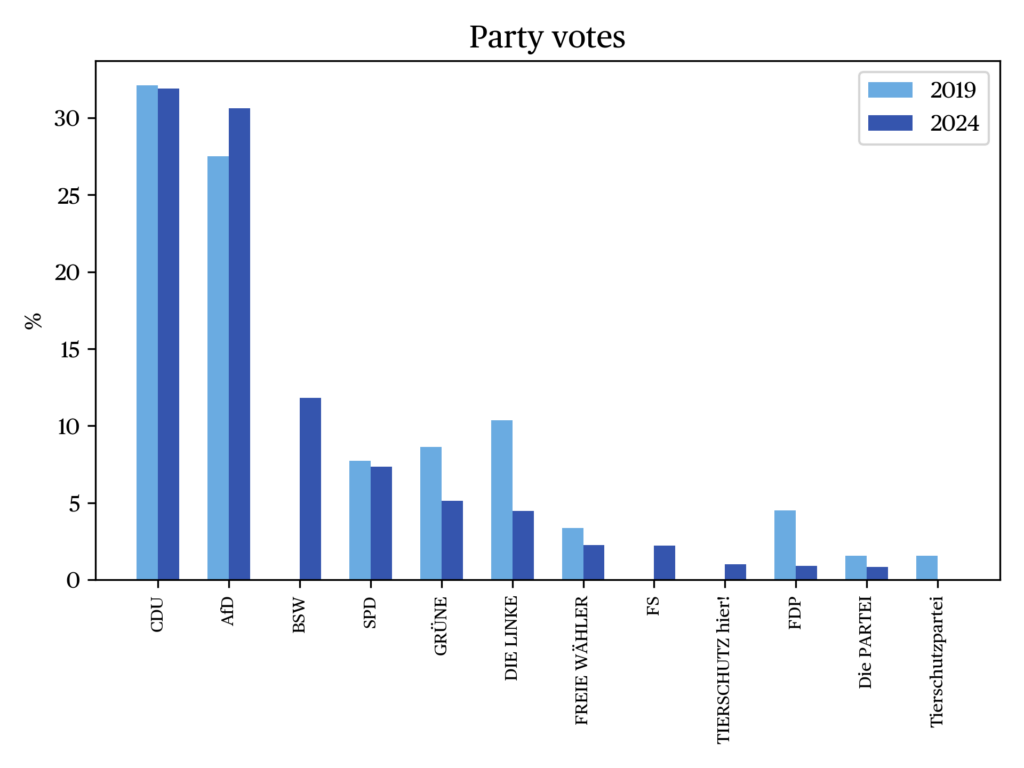

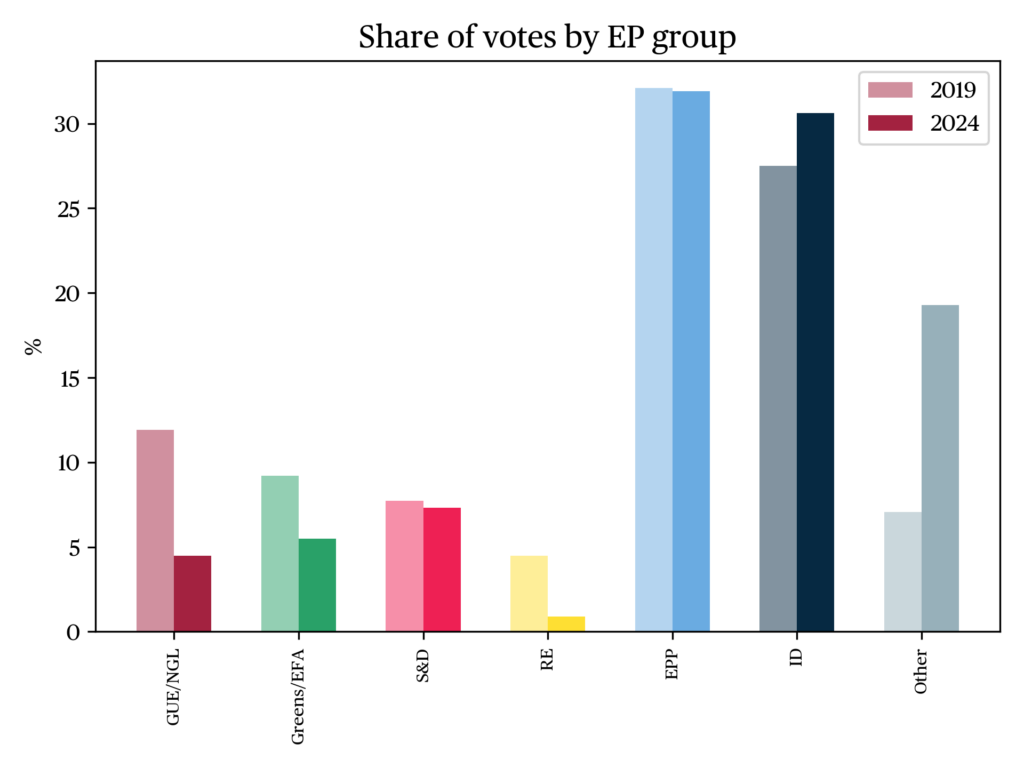

From 2019 to 2024, the Free State of Saxony was governed by a coalition of the Christian Democratic Union (CDU, EPP), Alliance 90/The Greens (Greens/EFA), and the Social Democratic Party of Germany (SPD, S&D), the so-called “Kenya coalition.” For the first time since 1990, such a three-party alliance had become necessary in the historical CDU stronghold as the only combination excluding both the Alternative for Germany (AfD, ESN) and The Left (GUE/NGL) from government. Although the CDU received the most votes (32.5%), it also suffered losses alongside The Left and the SPD, while the Greens recorded slight gains. However, the big winner was the AfD, which saw a significant increase to 28.4% (+17.8). Consequently, the 2019 election brought about a fundamental shift in the balance of power.

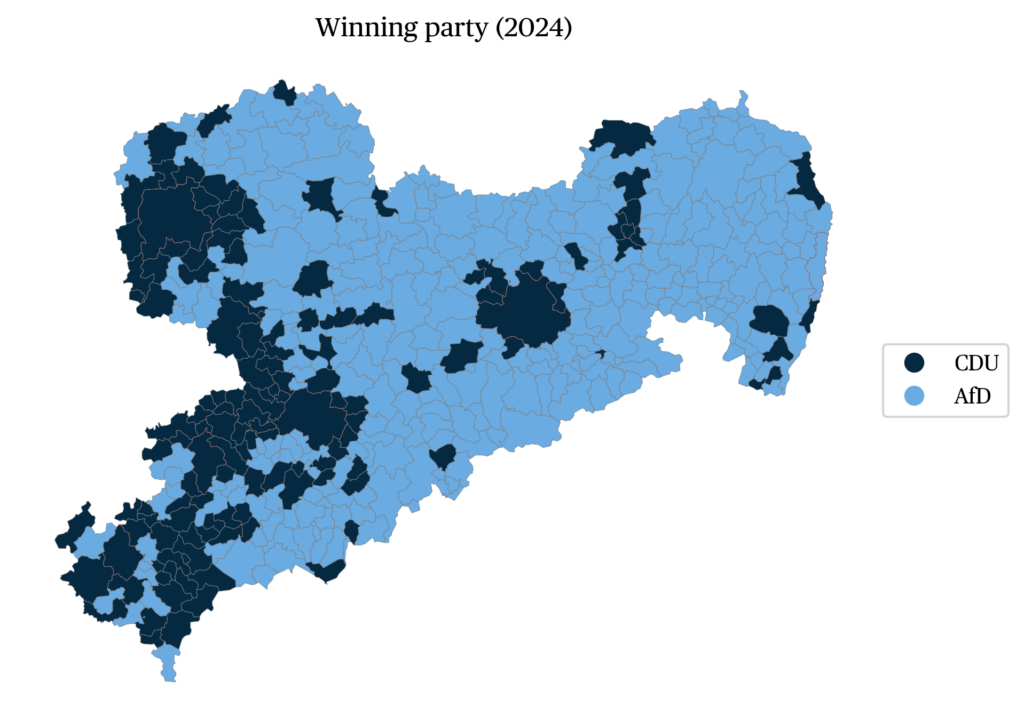

In the run-up to the Saxon state elections on 1 September 2024, three trends became apparent. The first major trend was the strength of the AfD, which could count on roughly 30 percent support in Saxony. In the European Parliament elections three months earlier, the AfD had become the strongest party and dominated in all districts and cities. The second major fact was the weakness of the parties in the federal government’s traffic-light coalition, whose nationwide approval ratings had dropped to an extreme low over the past twelve months; only 16% were satisfied with the government of SPD, Greens, and FDP (RE) (Infratest dimap, 2024). This was expected to impact the state election in Saxony. Thirdly and finally, the newly founded Alliance Sahra Wagenknecht (BSW) emerged as a significant new player in the political arena. Following her departure from the party, the former Left leader was able to attract not only its voters, but also non-voters (Infratest Dimap, 2024a). Despite being newly founded and having limited staffing, polls showed that the BSW had a good chance of entering the state parliament. Forecasts predicted support of between 12% and 15%.

Against this backdrop, two questions arose. First, would the CDU once again become the strongest party, as in the last state election in 2019? Second, would the partners of Saxony’s Kenya coalition – Alliance 90/The Greens and the SPD – win enough votes to renew this coalition? Most importantly, there was a real possibility that the Alternative for Germany (AfD) party could win the election in Saxony with an absolute majority – a prospect that alarmed all democratic parties, as it would be the first time this had happened in any federal state.

Complicating matters was the fact that the campaign was shaped not only by citizens’ dissatisfaction with the federal government’s policies but also – more surprisingly – by the Ukraine war. This defied institutional logic, given that foreign policy is the exclusive responsibility of the federal government, with no influence from state governments. Nevertheless, Sahra Wagenknecht succeeded in polarizing the debate around this issue (see below for more). Two parties that opposed the federal government’s official Ukraine policy, the BSW and the AfD, competed in this election. Indeed, East Germans are significantly more sceptical about supporting Ukraine. For example, a June poll (Forschungsgruppe Wahlen 2024) found that 45% favoured reducing military aid. Therefore, it seemed a tactical move when Minister-President Kretschmer (CDU) took a position on the issue that differed significantly from that of his federal party by advocating the cutting of military aid to Ukraine.

The election result

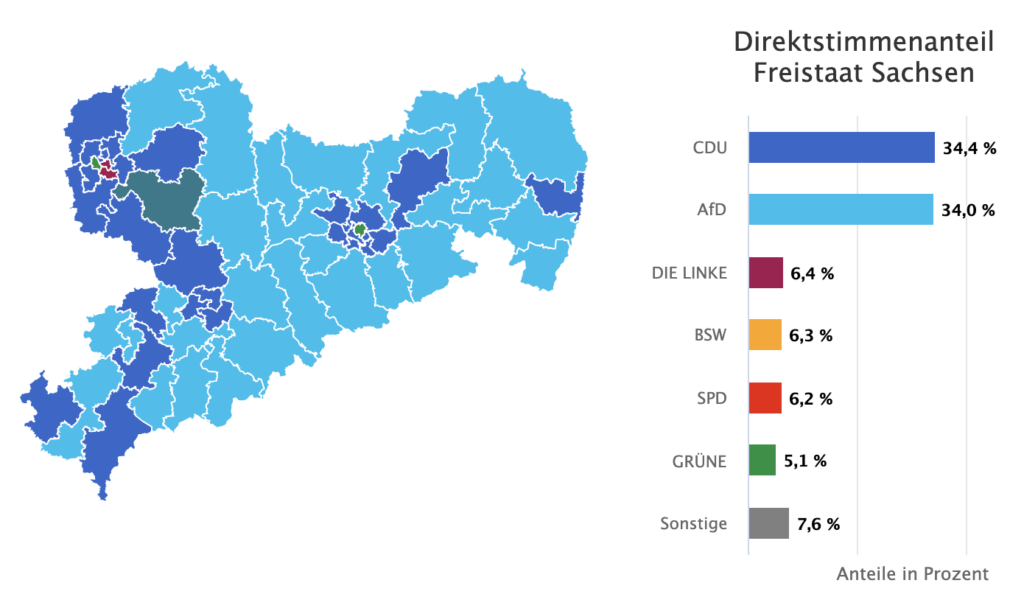

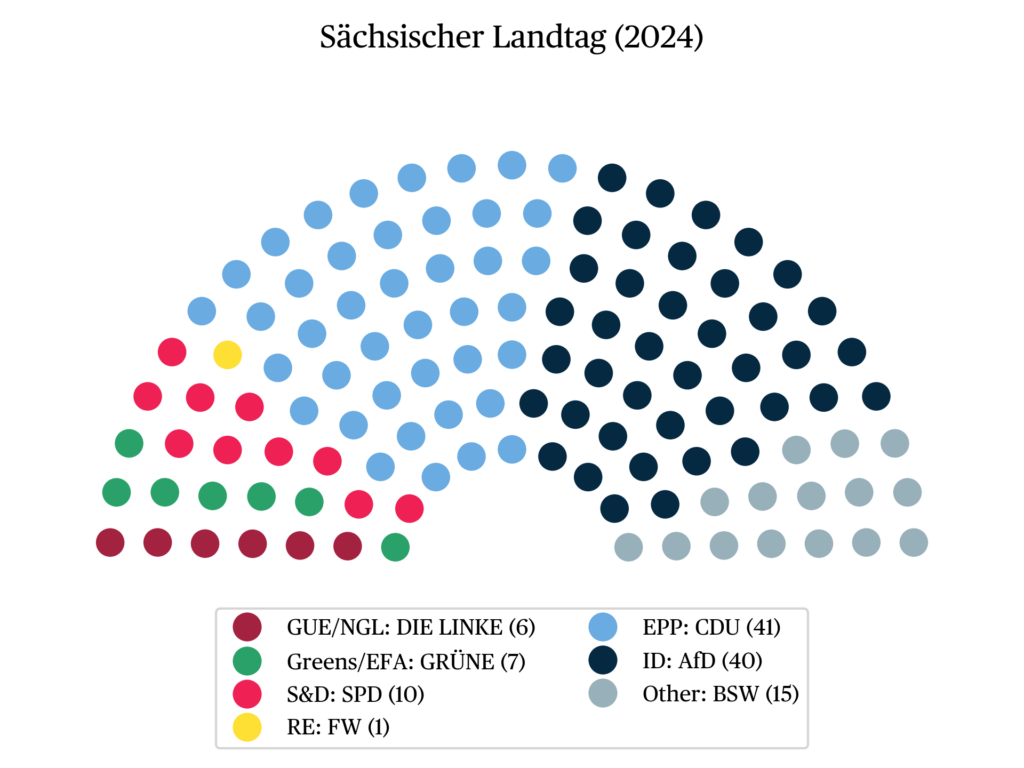

The election on 1 September ended in a narrow lead for the CDU over the AfD, a success for the BSW as the third-strongest force, and poor results for the SPD, Greens, and The Left. The biggest losses were recorded by The Left (-5.9pp) and the Greens (-3.5) and the biggest gains by the BSW (+11.8) and AfD (+3.1). Both the CDU and SPD suffered marginal losses. Voter turnout, at 74.4%, was the highest in the state’s history.

Source: wahlen.sachsen.de.

The new state parliament also includes The Left, who have six seats, and the Free Voters, who have one seat, both thanks to direct mandates (see “the data”).

This election result ruled out a continuation of the previous Kenya coalition of CDU, SPD, and Alliance 90/The Greens, as together these received just under 48% of the vote. As a result, Minister-President Kretschmer faced the decision to seek another coalition option (see below “Coalition negotiations”).

It is worth mentioning the result of the Free Saxons party, who won 2.2% of the vote. The state Office for the Protection of the Constitution has classified this party as “confirmed far-right extremist”. Founded in 2021, the Free Saxons are a neo-Nazi party that operates as a movement and networking party, as well as providing an umbrella for various right-wing protest movements (Kiess & Nattke, 2024). Together, the success of the AfD’s (30.6%) and Free Saxons’ (2.2%) paints an alarming picture: one-third of voters cast their ballots for parties considered to be far-right extremist (Verfassungsschutz Sachsen n.d.).

Sahra Wagenknecht: Shooting star and one-woman show

This brief excursus on Sahra Wagenknecht and the BSW highlights some special features relevant not only to the party landscape in Saxony but also in other East German states, as shown in the state elections in Brandenburg and Thuringia also held in 2024. Despite having only founded her new party in January 2024, with hardly any internal institutionalisation, Sahra Wagenknecht attracted an unexpectedly high number of votes in the European Parliament election in June 2024. This gave the party additional momentum and raised expectations of success, particularly in the state elections in eastern Germany, where it was expected to enter the state parliaments. In summer 2024, polls recorded voting intentions of 15% for the BSW in Saxony, dropping to 12% just before the election. The result of 11.8%, however, indicated a strong influx of voters, translating into 15 seats and giving the party a strong position in coalition negotiations (see below).

Thematically, Sahra Wagenknecht’s messaging focused mainly on radical foreign policy demands which aimed at branding the BSW as a “peace party,” especially in Eastern states. The party called for reducing support for Ukraine, stopping arms deliveries and rejecting the planned stationing of US intermediate-range missiles previously agreed between the German and US governments. She also made clear that these demands would be brought into any potential coalition negotiations as conditions. Overall, the BSW’s program can be described as a mix of left- and right-wing populist positions, combining nationalistic migration policies with a socialist social agenda. With this mélange of culturally nationalist-chauvinist and economically state-interventionist positions, Wagenknecht seeks to capitalize on widespread dissatisfaction with the government, but also with the overall performance of democracy in Germany. Ideologically, the BSW can be classified as left-authoritarian (Hillen & Steiner, 2020), with a left-wing economic policy stance and strong support for state intervention going hand in hand with an authoritarian value orientation. The party adopts a rather NATO-critical and EU-sceptical stance on foreign and security policy (Wagner & Wurthmann, 2025). Consequently, the BSW provides an alternative approach to migration policy for voters who are critical of immigration but cannot align themselves with the radical, extremist stance of the AfD. On economic policy issues, the BSW is less radical than The Left and tends more toward the center (Jankowski 2024). Moreover, BSW’s supporters exhibit a significantly higher potential for populism than is the case with other parties. This also explains the success of Wagenknecht’s populist communication strategy (Jankowski, 2024; Thomeczek, 2024).

How did this result come about? Election analysis

Analyses by Infratest Dimap (2024b) showed that the most important issues influencing voting decisions were social security, migration, social security and the economy. Looking at age cohorts, the difference between 18–34-year-olds and those over 65 is striking: for younger voters, social security was by far the most important issue (35%), while older voters named social security and immigration (20%) and Russia’s war against Ukraine (15%) as decisive. CDU voters prioritised economic development, while AfD voters prioritised immigration, SPD and BSW voters prioritised social security, and Green voters prioritised climate protection

A recurring question, also relevant in the Saxony state election, is whether the strong support for the AfD and the new populist party BSW is a sign of protest against the federal or state government, or if these parties have a core electorate that identifies with them and votes for them out of conviction.

For the 2024 election, Infratest Dimap (2024b) survey results reflect that the voting behaviour of citizens who chose AfD and BSW differs markedly from that of all other parties’ voters: they were by far less likely to say they voted out of conviction and more likely to say they voted out of disappointment with other parties. Among those who voted for the AfD, most also said they liked that the party advocates limiting immigration. This aligns with the dominant concern among the electorate on the issue of migration. By contrast, the issue that was most decisive for BSW voters was Wagenknecht’s heavily foregrounded stance on relations with Russia and limiting arms deliveries to Ukraine. This shows that the classic mobilisation issue of the AfD – migration and anti-immigration policy – was just as successful in winning over voters as the war issue. Despite the latter not being a state-level issue, Sahra Wagenknecht promoted her stance on it, which ultimately became her trademark.

Minister-President Kretschmer was able to score points in various areas. First, he is the most popular politician in the state. Compared to the last state election, he has hardly lost any popularity. In terms of voter satisfaction with the three governing parties CDU, SPD, and Greens, the CDU was clearly ahead with 42%, compared to SPD (27%) and Greens (15%). At the same time, the CDU was by far the party most trusted to find good solutions (34%, Infratest Dimap 2024b). Even the AfD, with 21%, did not come close to this figure. By contrast, competence ratings for all the other parties were single-digit. Even when broken down by individual issues, the CDU performed best overall, providing most convincing in terms of content – also ahead of the AfD and well ahead of the BSW.

Coalition negotiations

A the seat distribution no longer permitted a continuation of the previous coalition, Minister-President Kretschmar had to explore other options. The CDU, SPD, and BSW began talks for a so-called “Blackberry coalition”, drawing up a joint paper as the basis for their exploratory talks. As a condition for entering a coalition, the BSW demanded that a commitment to “peace policy” be enshrined in the coalition agreement. Kretschmer had no problem with this – despite criticism from his federal party. However, the exploratory talks for the Blackberry coalition failed after a few weeks. BSW broke off talks in early November 2024, citing disagreement on “peace”, migration policy, and finances. For the CDU’s and SPD’s negotiators, this step came as a surprise (Meyer 2024). Even though Sabine Zimmermann, the BSW’s chairwoman in Saxony, denied this, criticism remained that the withdrawal from the talks was directed by the federal party – meaning Wagenknecht herself.

Subsequently, the CDU and SPD negotiated a coalition agreement aiming for a minority government. This model is a first in Saxony, especially in a state historically accustomed to stable majorities. The agreement was approved at the CDU party conference and by an SPD membership vote. Since the black-red coalition falls ten votes short of a majority, it must rely on support from other parties. Kretschmer also required this external support to secure his re-election as Minister-President on 16 December 2024. In addition to Kretschmer, the AfD’s state leader Jörg Urban and the Free Voters’ candidate Matthias Berger also ran for Minister-President. After failing to secure the required majority in the first ballot, he was elected in the second round with 69 of 120 votes, including some from The Left, the BSW, and the AfD.

Governing in a minority: difficult conditions

It was clear that governing with a minority against a strong AfD opposition would create difficult conditions for the new executive. In response, the coalition introduced a new mechanism whereby proposals and bills from the Saxon state government are sent to the state parliament ahead of any formal deliberation, so that all members, factions, and groups can contribute suggestions to be incorporated into the government’s legislative process. In this way, the CDU and SPD hope to establish a new way of buildling cross-faction consensus. Regarding the AfD, the Minister-President confirmed that there would be no cooperation, adding that the coalition mechanism is also intended to prevent the AfD from playing the victim by claiming that no one talks to them and that they have no way to influence anything.

Unlike in Thuringia and Brandenburg, the AfD in Saxony does not hold a blocking minority with which it could obstruct or influence key decisions or appointments (e.g., intelligence oversight, judicial selection committees) in sensitive rule-of-law areas. However, it is entitled to chair parliamentary committees.

Like those in Thuringia and Brandenburg, the new state government in Saxony will be a test case for governing from the democratic centre in the face of strong far-right opposition. The path of a minority government in Saxony contains even greater challenges than in the other two states.

The data

References

Infratest dimap (2024). ARD-DeutschlandTREND September 2024.

Forschungsgruppe Wahlen. (2024). Landtagswahl in Sachsen 2024.

Freistaat Sachsen (2024). Wahlergebnisse 2024.

Hillen, S., & Steiner, N. (2020). The consequences of supply gaps in two-dimensional policy spaces for voter turnout and political support: The case of economically left-wing and culturally right-wing citizens in Western Europe. European Journal of Political Research, 59, 331–353.

Infratest Dimap. (2024a, 2 September). Wählerwanderung Sachsen 2024. Tagesschau.

Infratest Dimap (2024b). Wahlentscheidung.

Jankowski, M. (2024). Das Schließen der Repräsentationslücke? Die Wählerschaft des Bündnis Sahra Wagenknecht – Eine Analyse basierend auf Paneldaten. Politische Vierteljahresschrift.

Kiess, J., & Nattke, M. (2024). Widerstand über alles. Wie die Freien Sachsen die extreme Rechte mobilisieren. Leipzig: edition überland.

Meyer, I. (2024, 6 November). „Das haben wir nicht kommen sehen“. Süddeutsche Zeitung.

Thomeczek, J. P. (2024). Bündnis Sahra Wagenknecht (BSW): Left-wing authoritarian—and populist? An empirical analysis. Politische Vierteljahresschrift, 65, 535–552.

Verfassungsschutz Sachsen (n.d.). Freie Sachsen.

Wagner, S., & Wurthmann, L. C. (2025). Das Bündnis Sahra Wagenknecht im deutschen Parteiensystem. In Bündnis Sahra Wagenknecht – Vernunft und Gerechtigkeit (BSW). essentials. Wiesbaden: Springer VS.

citer l'article

Marianne Kneuer, Regional election in Saxony, 1 September 2024, Sep 2025,

à lire dans cette issue

voir toute la revue