Regional election in Schleswig-Holstein, 8 May 2022

Oliver Drewes

Researcher, University of TrierIssue

Issue #3Auteurs

Oliver Drewes

Issue 3, March 2023

Elections in Europe: 2022

Introduction and context

In the run-up to the state election that was held in Schleswig-Holstein on May 8, 2022, a few key issues shared with other European regions have received the most public attention. Not only the still ongoing Covid-19 pandemic was a present topic, but also rising inflation figures, Russia’s war against Ukraine (that broke out at the beginning of the year) and the associated challenges for German energy security. In view of this context, it would not have been no surprise if the election outcome had been shaped by these very issues. In the end, however, factors arising from the specific characteristics and structure of state politics appear to have played a must greater role than the political situation might have suggested: 70% of voters declared that state politics was a decisive factor in their voting decision, with only 26% citing federal politics (Forschungsgruppe Wahlen 2022). This is an important fact to keep in mind: the results are strongly influenced by state-specific structures, characteristics and circumstances.

Besides these important issues, the popularity of political leaders, but also the party and coalition equilibria that marked the last parliamentary term, greatly contributed to the outcome. Prime Minister Daniel Günther (CDU, EPP) enjoyed a popularity rating of 76% (Infratest dimap 2022d), well above average in comparison with other regional leaders. He had governed relatively “quietly” (Becke 2022) despite leading Schleswig-Holstein’s first ever three-way coalition, and his government experienced an overall satisfaction rating of 75% (Infratest dimap 2022d). Hence, it can be argued that the outcome of the election owes significantly to the popularity of the prime minister and his governing style. In the following sections, we will first analyze the performance of parties and party leaders, then explore programmatic and geographic trends and examine the coalition situation in Schleswig-Holstein in more detail, and finally summarize the significance of this election for the state’s party system.

Results and change

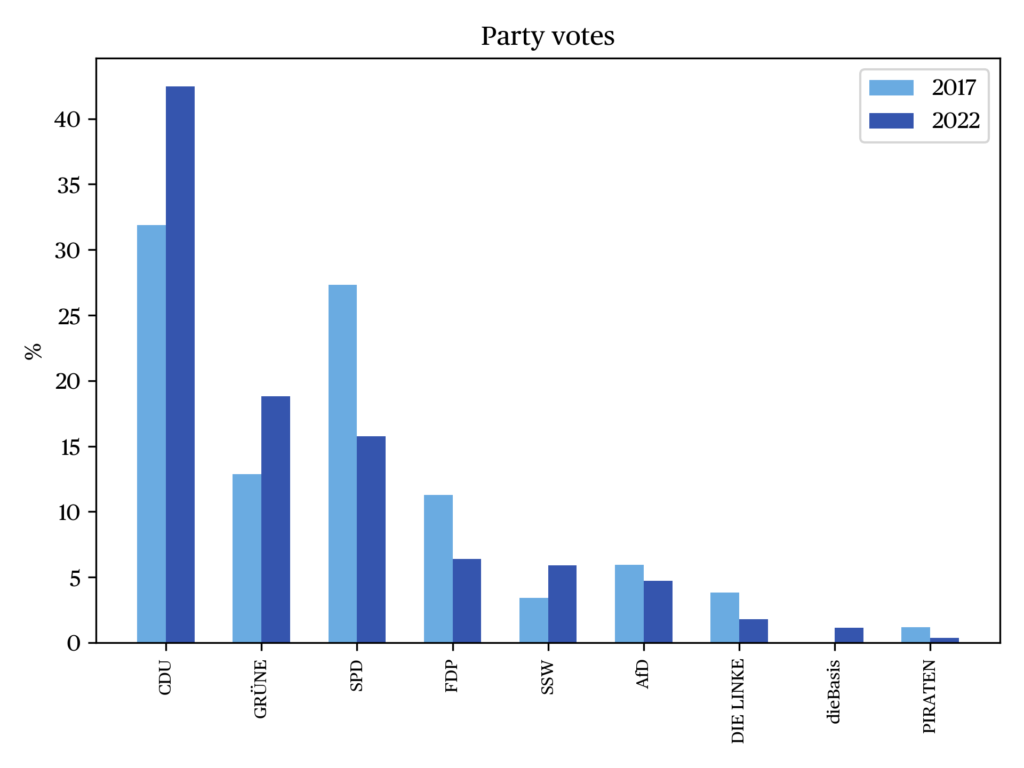

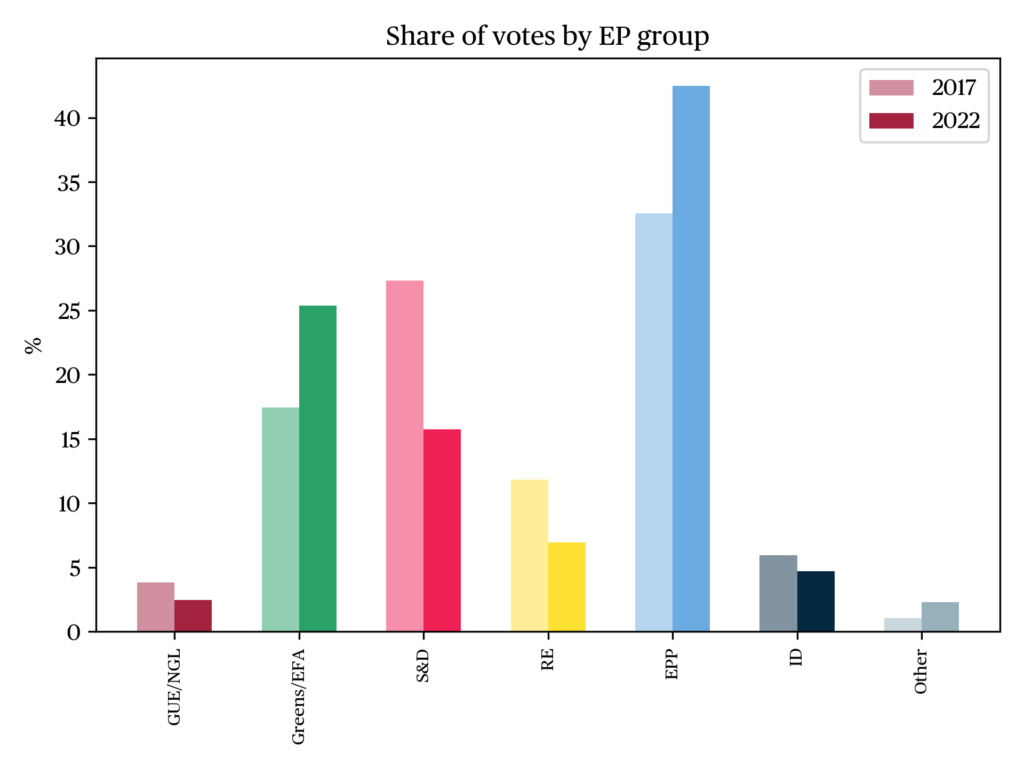

The Christian Democratic Union (CDU, EPP), which had already won the 2017 state election, extended their lead (+ 11.4 pp) in 2022, garnering 43.4% of the popular vote. This put it 27.4 pp ahead of the Social Democratic Party of Germany (SPD, S&D), which had trailed the CDU by only 4.7 pp in 2017 and was now unable to compete with the CDU. The SPD ended up with 16% of the popular vote, losing 11.3 pp. For decades, the SPD and CDU were the two main parties competing for political dominance in Schleswig-Holstein, but never was one of them able to permanently assert itself as the dominant force. By inflicting on the regional SPD their most severe electoral defeat in history, the Schleswig-Holstein CDU was able to modify the previously existing competitive situation between the two parties, at least in the medium-term. This allowed Conservatives to assert a clear claim to leadership for themselves in the region, while forcing the SPD to enter a phase of self-reflection. Although the SPD narrowly won the federal elections in Germany in September 2021 and currently holds the office of chancellor, its role and performance in Schleswig-Holstein are not comparable to its role and performance in the federal government. Leadership, in particular, plays too large a role in the results of both elections for this to be the case. To a very high degree, the popularity of the prime minister was relevant to the electoral decision (Infratest dimap 2022a). With a satisfaction rating of 75%, Daniel Günther is among the most popular minister presidents nationwide; when considering the popularity of incumbent minister presidents at the time of the last election, he is in fact Germany’s most popular minister president (Infratest dimap 2022b). Within the state, too, he is by far the most popular politician (Infratest dimap 2022c). The latter is hardly surprising, however, since prime ministers, who enjoy greater political and media attention, are usually much better known than other state politicians. Moreover, Daniel Günther is depicted as an approachable, pragmatic and less ideological politician (Becke 2022), and the coalition he led performed well in the polls, with a satisfaction rating of over 70%, even reaching over 80% among supporters of the coalition parties (Infratest dimap 2022d). For the first time, Günther had succeeded in forming a coalition consisting of three parties (CDU, FDP — RE and Greens — Greens/EFA) and in leading it to the next regular state election.

The SPD eventually placed third in the 2022 election, allowing another party, the Greens, to celebrate a historical success. Not only did the Greens, in line with a nationwide upward trend, gain votes in Schleswig-Holstein, but, with an increase of 5.4 pp to 18.3% of the popular vote, they even achieved an unprecedented success and moved into second place ahead of the SPD. On the other hand, the FDP shared the SPD’s fate in suffering an electoral defeat. While the FDP had been able to win 5.1 pp more votes in the 2017 election, it now came dangerously close to the 5% hurdle, which sets the mark for entry into the state parliament, gathering only 6.4%.

The AfD (Alternative für Deutschland, ID) incurred an even more dramatic loss than the SPD and FDP, despite losing only 1.5 pp. With a final result of 4.4%, it fell short of the required 5% threshold and lost its seats in the state parliament. The party had entered the state parliament for the first time in the aftermath of the 2017 election. The party’s downfall was mainly due to internal disputes, which led to debates about the quality of its leadership. For example, the AfD’s regional parliamentary group broke apart after the party’s regional spokeswoman was expelled from the party (triggering a still ongoing legal dispute) due to contacts with the far-right scene (dpa 2018), and another deputy left the party after calling it radicalized (dpa 2020). The loss of two deputies shrank the AfD’s representation to three deputies, whereupon it lost its status as a parliamentary group.

The SSW (Südschleswigscher Wählerverband or Southern Schleswig Voters’ Association, Greens/EFA), the party of the Danish minority, was the fifth and last party to enter the state parliament in Kiel. The fact that the party achieved 5.7% of the vote (+ 2.7% pp) did not affect their capacity to enter the state parliament, because the party, who represents the Danish national minority, is exempt by law from the 5% hurdle. Nevertheless, this result constitutes the party’s greatest success in a state election.

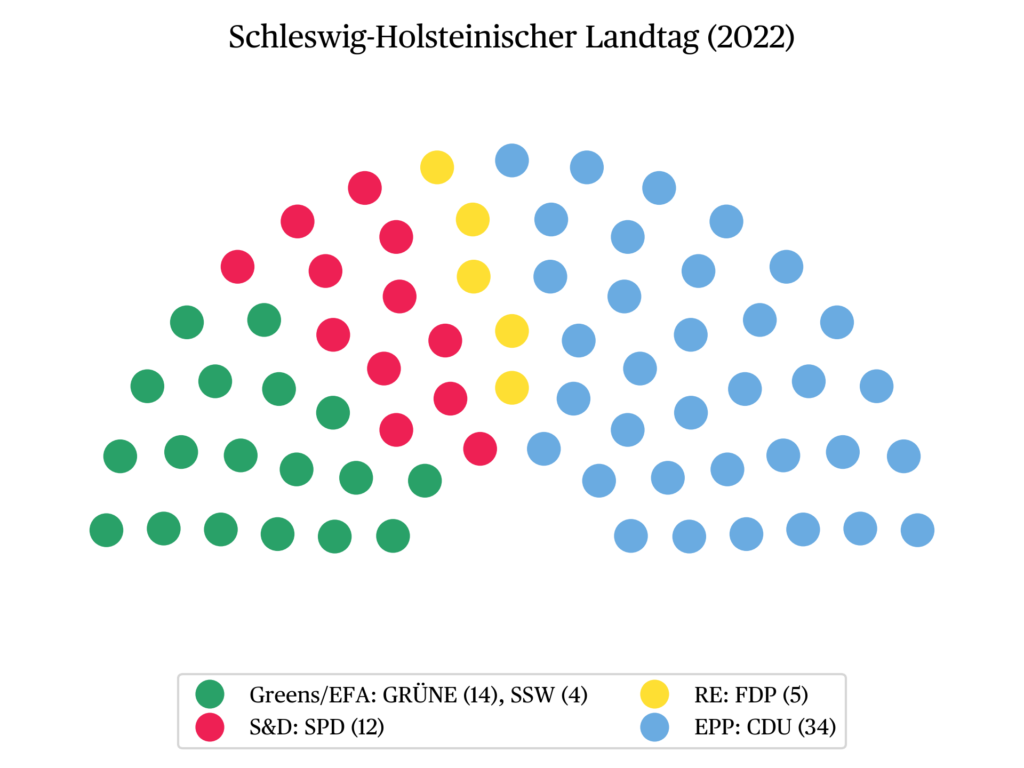

The election results gave rise to a state parliament composed of five parties, in which the CDU, by far the strongest force with 34 seats, narrowly misses the majority (35 seats). Thus, the CDU is still dependent on at least one coalition partner (see the data panel).

Programmatic trends

When looking at the political issues that have played a role in citizens’ voting decisions, a differentiated picture: issues that have been decisive in the election are not always those that are viewed as constituting the most pressing problems in Schleswig-Holstein specifically. Thematically, “climate,” “energy supply,” “price increases” and “education” (Infratest dimap 2022e) were almost equally important for the electoral decision. However, these topics are not very specific to the political situation in Schleswig-Holstein, so a more precise question about the problems facing the state and the perceived competence of the different parties in various policy areas provides somewhat deeper insights into the state’s self-perception. For example, 27% of respondents consider “mobility and transport,” 20% “energy policy or energy transition” and 19% “education and training” to be the most important problem in the state (NDR/Infratest dimap 2022). The still ongoing Covid-19 pandemic, which had occupied society for two years, was named as the most important problem by only 10%. At the same time, the CDU obtained high competence scores on economical and educational issues, while the Greens performed well in energy and environmental policy. The SPD stands out in family policy and social justice, which likely did not win it many votes, since these issues were not nearly decisive for the election; in the same time, the CDU and the Greens were both deemed competent on issues that were most important at the time of the election.

In comparison to other German states, the assessment of the economic situation stands out, with 69% of respondents (Infratest dimap 2022f) assessing the economic situation as good. This is not only a high value in a comparison between the federal states, but is particularly remarkable because Schleswig-Holstein is a rather “structurally weak” (Deutsche Fördermittelberatung 2022) state within Germany, characterized by below-average industrialization and above-average reliance on agriculture. Although Schleswig-Holstein has a rather low unemployment rate (5.3%) and an average household income compared to other German states, its infrastructure and economic strength remain behind those of other German states. The belief that Schleswig-Holstein is economically on the right track and popularity of te state government, as well as the fact that the prime minister is credited with very good crisis management in the pandemic, are likely to have contributed significantly to the confirmation of Daniel Günther as prime minister and the CDU as a senior coalition partner.

Geographic trends

At just under 60%, voter turnout was low in historical comparison. The reasons for this low figure cannot be precisely identified from the available data, but this fact may be connected with a general downward trend in voter turnout that can also be observed nationwide.

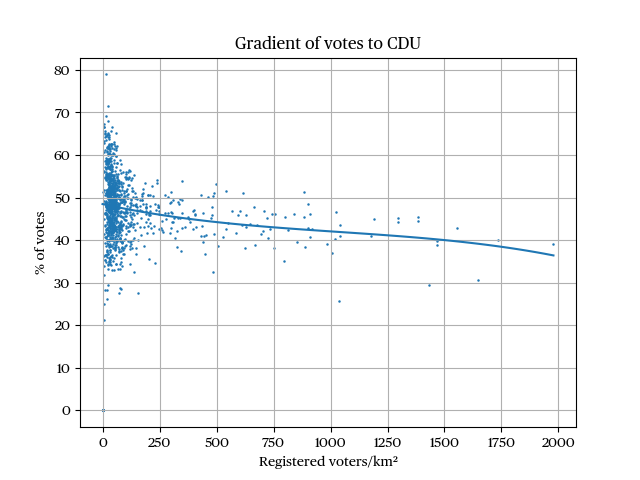

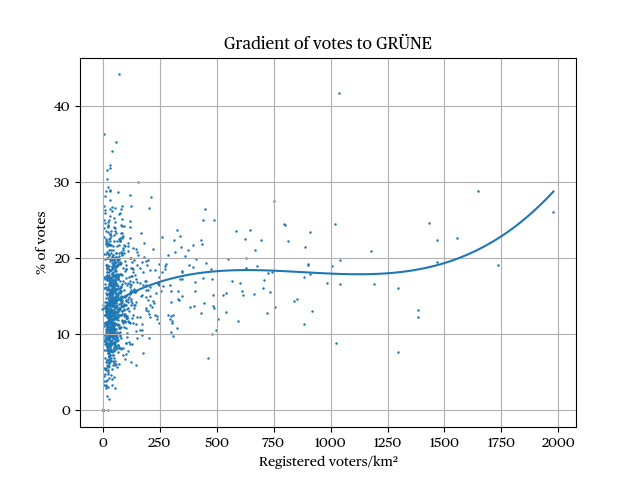

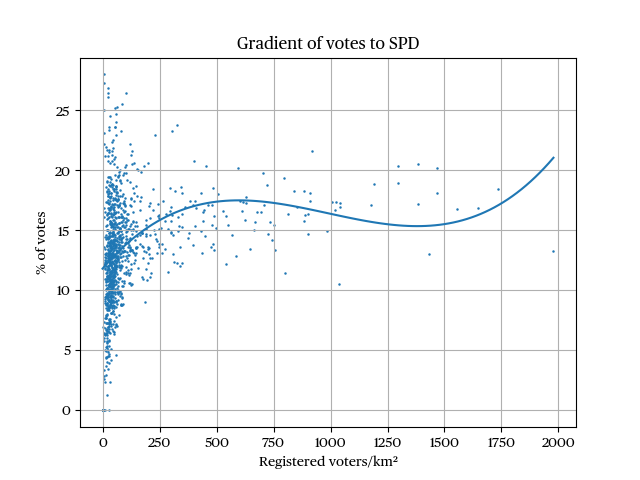

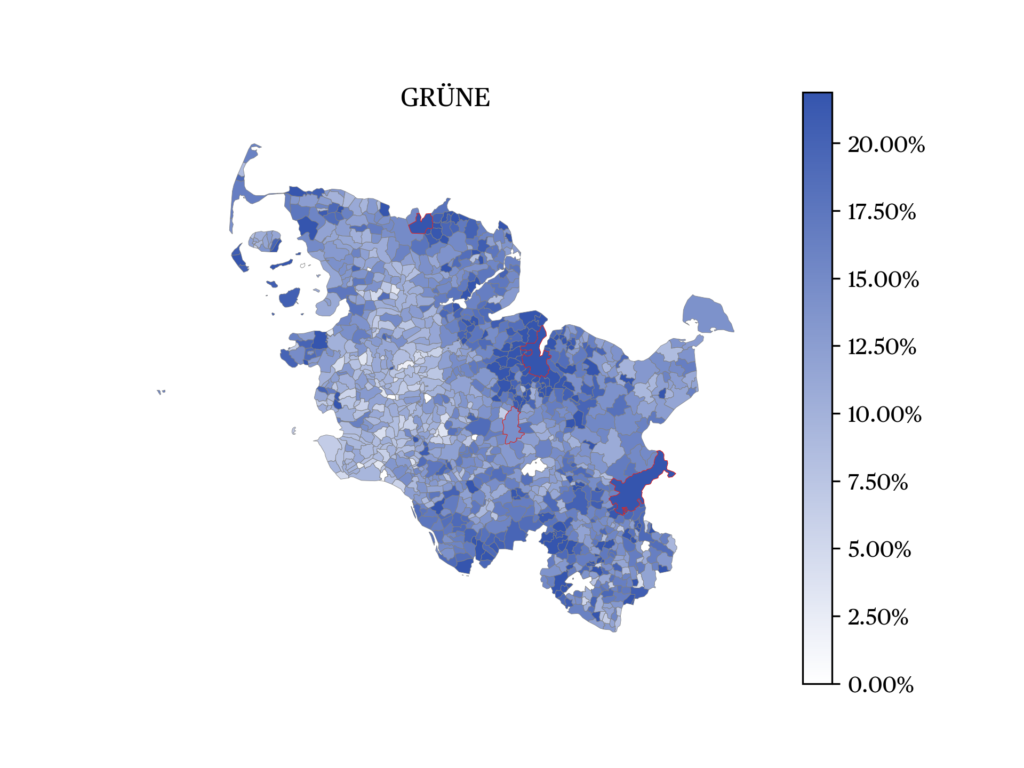

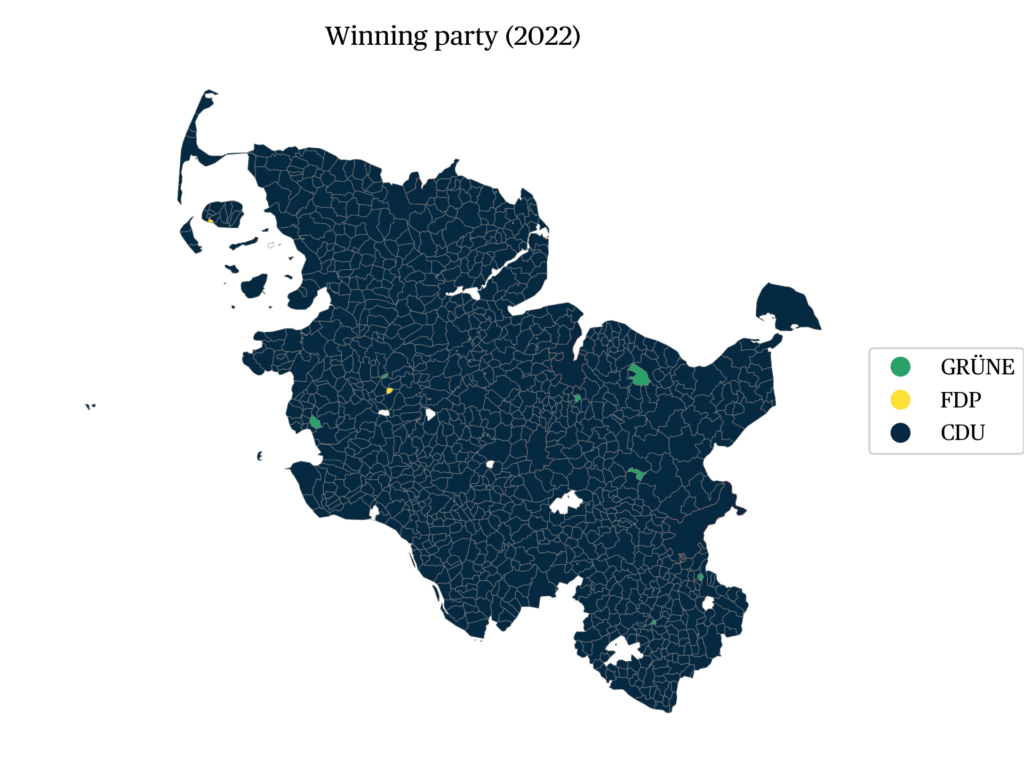

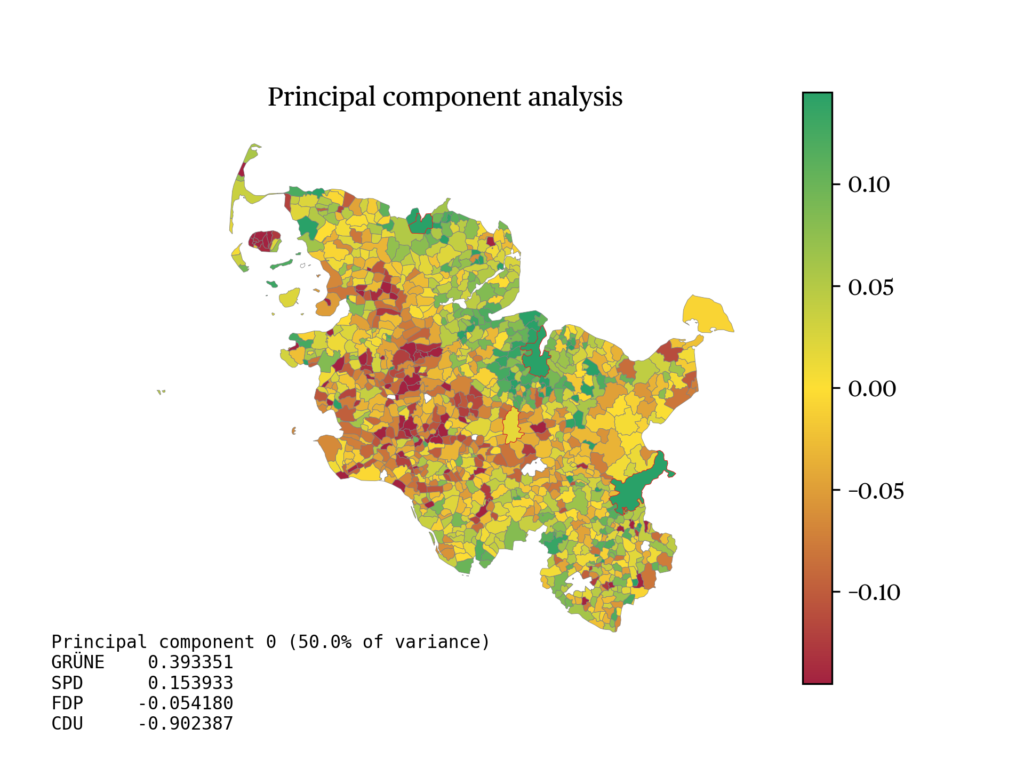

The analysis of the constituency-level results clearly shows the dominance of the CDU, which won all but two constituencies (out of a total of 35). The electoral system in Schleswig-Holstein provides for two votes. The first vote is used to elect a direct candidate in each constituency, while the second vote goes to a party list. Thus, the CDU’s ability to win almost all constituencies demonstrates their strong standing in most areas of the region: only the two urban constituencies in Kiel and Lübeck were won by the Greens, illustrating once again that the Greens’ electorate is strongest in urban areas and university towns. Where the Greens and the SPD have a tendency to perform better in more urban areas (Figures b and c), the CDU has a clear tendency to be stronger in rural areas (Figure a).

The Greens’ primary reliance on urban voters is evident (Figure d). Compared to the last state election, the correlation between the Green vote and urbanization is greater (Figure b), which indicates a stronger polarization of the municipality-level vote. Green voters primarily live in and around Lübeck or Kiel and next to Hamburg. Markedly rural areas, on the other hand, are a major challenge for the Greens. The major difference between rural and urban milieus in terms of their propensity to vote primarily for the CDU and the Greens, respectively, stands out in a principal component analysis that draws attention to how people voted in cases that deviate from the regional average (Figure e).

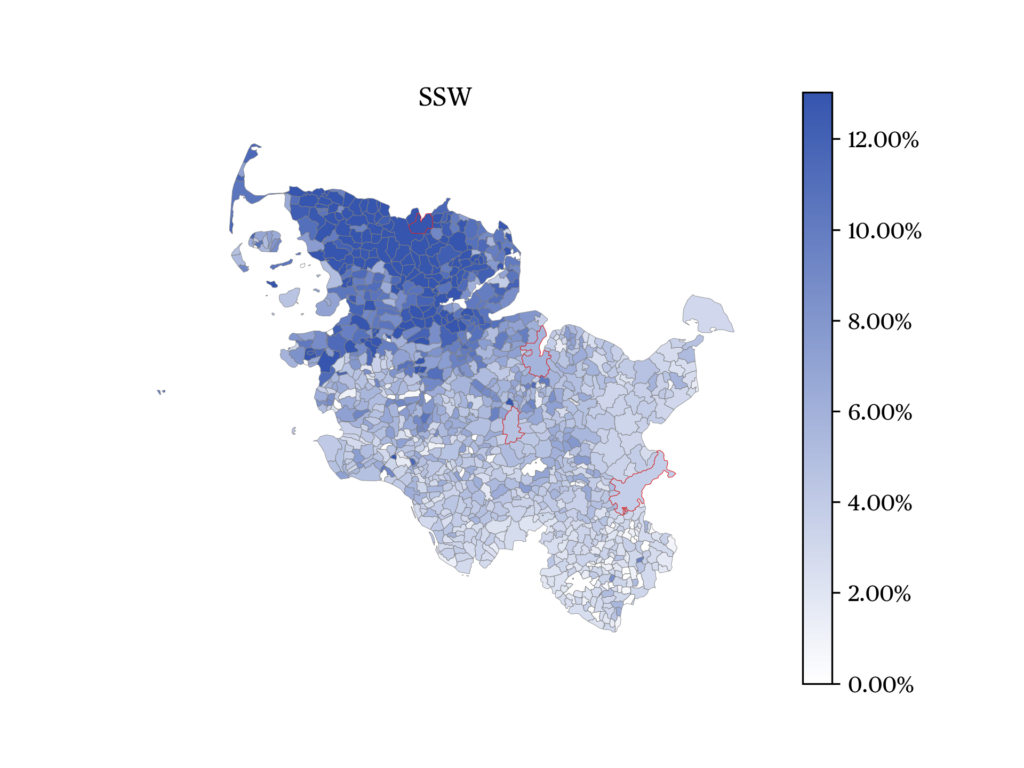

In contrast to both the CDU and Green vote, the SPD vote does not exhibit any clear geographic pattern; as before, the SPD appears to be capable of attracting voters from all areas of the region. The clearest, but also most logically understandable, geographic clustering of votes concerns the SSW, whose electorate is concentrated near the Danish border (Figure f).

For the FPD, only marginal regional differences can be observed. The party only appears to enjoy slightly greater support in the western part of Schleswig-Holstein than in the rest of the country. Geographical differences for the AfD are similarly small. Its electoral performance is slightly higher on the border with the eastern German state of Mecklenburg-Western Pomerania than in the rest of the country.

Coalition formation

A three-way coalition was formed for the first time in Schleswig-Holstein in 2017, bringing together the CDU, the FDP, and the Greens. Given the ideological cleavages that divide the coalition partners, such a coalition model is deemed difficult to manage. Hence, the fate of the coalition following this year’s election appeared uncertain, even though Daniel Günther declared himself open to continuing the coalition in this format despite other coalition models being mathematically possible. The FDP’s poor electoral performance meant that it also had a weak negotiating position, although it had agreed to govern together with the CDU. At the same time, the increase in the Greens’ vote share meant that a third party would not even have been necessary for a majority, and that the FDP would have more to lose than to win by being in government: as an optional partner in the coalition, it would hardly have been able to impose its views. For that same reason, the Greens rejected Günther’s first impulse to continue the three-way coalition, instead proposing a two-party alliance. The fact that the CDU opted for the Greens as a coalition partner seemed to make tactical sense insofar as the Greens, as a stronger competitor (especially in climate policy), would otherwise have been likely to overtake them during the next term. At the same time, Günther shares the progressive stance of the Greens with regard to gender parity and political modernization – including within his own party.

Modernizing both the content and structure of its own policies is not unimportant for the CDU, whose electorate is becoming smaller and smaller in younger age cohorts (Infratest dimap 2022g), among whom Green voters are much more numerous (ibid.). Thus, the Greens are slowly emerging as a competitor to the CDU in terms of issues, demographics and, increasingly, personnel, as Green politicians play a more an more important role in public life. Currently, Robert Habeck (Greens), the Federal Minister of Economics and the Environment and a former Minister of Agriculture and the Environment and Deputy Prime Minister in Günther’s cabinet until 2018, and Annalena Baerbock (Greens), the Federal Minister of Foreign Affairs, are among Germany’s most popular and successful politicians (ZDF PolitBarometer 2022). Although Habeck is no longer active in Schleswig-Holstein’s state politics, his visibility at the federal level had appeal and relevance for the election (Infratest dimap 2022h) in that his popularity (at the time of the election, he was Germany’s most popular politician (Infratest dimap 2022j)) provided a tailwind to the Greens. The Green’s lead candidate, Monika Heinold, may lie behind Günther in a direct comparison of satisfaction ratings with her political work, but she is by no means unpopular — especially when compared to the lead candidate of the SPD, Tomas Losse-Müller (Infratest dimap 2022i).

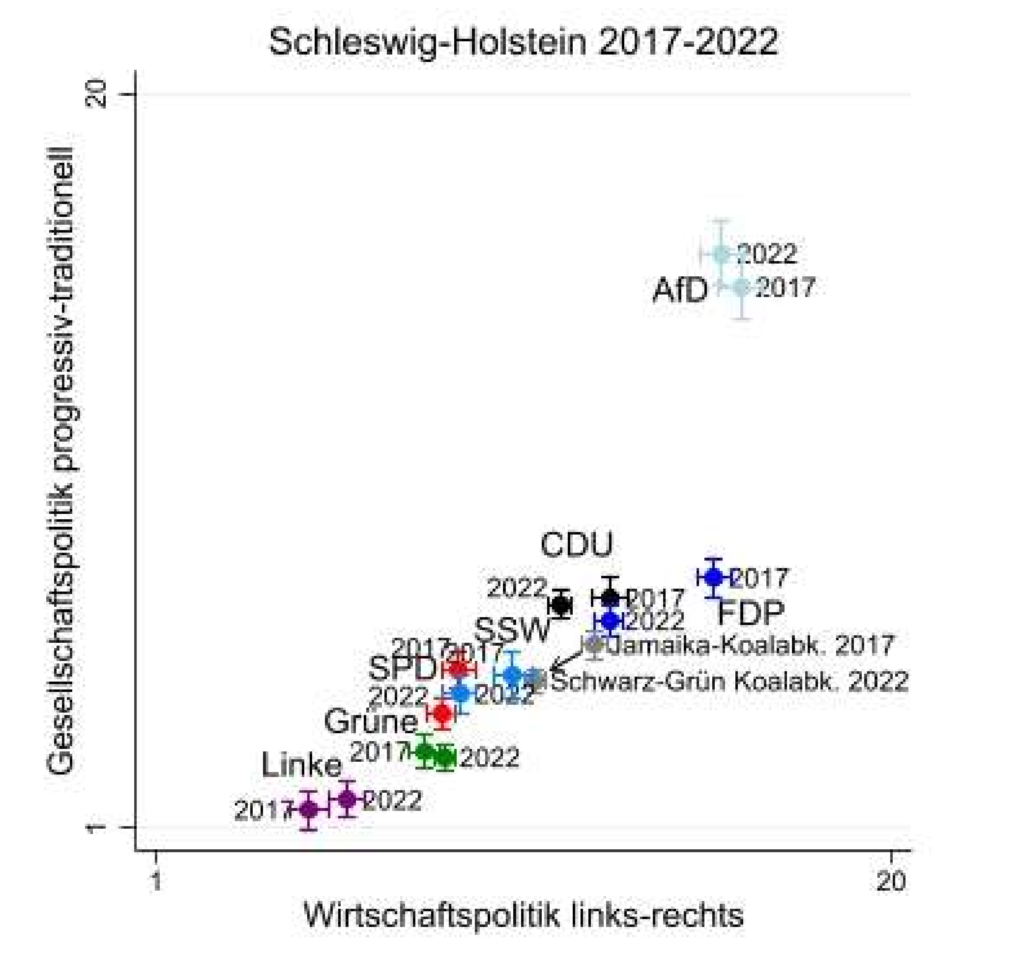

To explain why the CDU-Green coalition was formed, the scientific literature suggests a number of relevant mechanisms. The most prominent of these are the policy-seeking, vote-seeking, and office-seeking (Müller/ Strøm 1999), as well as the identity-seeking (cf. Sturm 2013), models. While policy-seeking parties strive to maximize overlaps with the political programs of their coalition partners, vote-seeking parties follow strategies that would optimize their future vote share, and office-seeking parties try to acquire the largest possible share of political offices. Additionally, identity-seeking parties attach great importance to mutual trust. The CDU and the Greens enjoyed the latter to a great extent during the previous legislative term. At the same time, ministries could be divided up based on different preferences: eventually, the Greens obtained the environment, social affairs and finance portfolios. In light of this distribution of ministries, and given the rapidity and smoothness of the negociation process that led to the signature of the new coalition agreement, the two-party alliance has began its term under very favorable conditions, showing no signs of instability. Of the three main models, the policy-seeking model appears least relevant to explain the formation of the coalition between the CDU and the Greens, since the FDP and the CDU are classically much closer to each other. both ideologically and programmatically, than the CDU and the Greens are (see Figure g). The office-seeking model appears more suitable, since in a coalition between the CDU and the Greens, offices can be easily divided on the basis of different preferences, competencies, and demands, than between the CDU and the FDP, which do not differ too much in these respects. Ultimately, the vote-seeking factor is of limited importance, as a continued coalition of the CDU, the Greens and the FDP would have been approximatively as popular (39% in favor) as the current coalition of the CDU and the Greens (38% in favor, see Infratest dimap 2022k). Only a coalition of the CDU and the FDP would have been less popular, at 31% (ibid.). Overall, the new government alliance can be explained in terms of the classical mechanisms of coalition theory “taking into account, on the one hand, the marginal conditions of government formation, such as voter behavior and strategic party competition, and, on the other hand, the expectations of voters and political actors regarding the future performance of governments.” (Bräuninger; Debus 2012: 174)

Owing to his landslide victory — his score of over 40% sets a record among contemporary CDU state premiers —, Günther puts himself in a powerful position within the federal party. At the same time, the Greens currently participate in government in eleven of the sixteen federal states and are slowly but steadily continuing their political ascent. Daniel Günther’s role in this state election campaign and the CDU’s strong result show that personalization is playing an increasingly important role in election campaigns, and that party loyalty is decreasing. As a result, competition between the parties increases considerably, and parties struggle to establish themselves in stable positions in the long run. After its defeat, the SPD is looking for a new political offer that can help it regain competitiveness. At least as long as Daniel Günther continues to govern with a firm footing, this is likely to be difficult. The FDP must analyze the considerable voter losses it suffered and seek new orientation in its new role as an opposition party. Whether the AfD will succeed in making a comeback in the next state elections remains doubtful, as debates about its leadership and internal power struggles continue. The fact that the party was put under observation by the Office for the Protection of the Constitution (Verfassungsschutz) in 2021 is likely to have severely harmed its reputation. As of 2022, the AfD still occupies an isolated position in the party system, where it has moved further and further to the democratic fringe.

Party system

In conclusion, the following core trends can be emphasized with regard to the development of the party system in Schleswig-Holstein, which differ only in part from those of other states and the federal level: Fragmentation, polarization and segmentation.

The fact that the AfD has left the state parliament, that the Left Party is still not represented in the state parliament, but that the SSW, as a unique case of a significant national minority party, is virtually guaranteed to win a few seats, leads to an overall medium fragmentation of the regional legislature, with an effective party number (calculated according to Laakso and Taagepera 1979) of 3.1 for 5 represented parties. In the last legislative term, the effective number of parties was 4.2. In a comparison with other German state parliaments, the current Schleswig-Holstein parliament is slightly below the average effective party count of 3.99 (for an average of 5.7 parties). Nevertheless, the level of fragmentation is such that one-party majorities are impossible — which does not come as a surprise in a political system featuring both proportional representation and a high degree of pluralism.

The polarization of the party system has decreased slightly between 2017 and 2022, and the 2022 coalition agreement between the CDU and the Greens has shifted the government’s position slightly towards the left in comparison with the 2017 coalition agreement (Figure g).

However, when one takes into account that the two parties on the fringes of the political spectrum — the Left Party and the AfD — are now no longer represented in the state parliament, polarization in the state legislature has decreased significantly.

With regard to segmentation, i.e. the relationship between arithmetically possible and politically feasible coalitions, we observe that four coalitions would have been arithmetically possible, but that only three of them were politically realizable. The SSW, FDP and Greens had all signaled their willingness to participate in the future government on election night. Only the SPD, after its bitter loss, could hardly meaningfully envision being part of the next executive. Thus, the segmentation in Schleswig-Holstein is rather low.

With all these characteristics, the party system in Schleswig-Holstein hardly stands out from those of other German states and roughly corresponds to the characteristics of the German party system as a whole.

References

Becke, Lisa (2022). Das Geheimnis des beliebtesten Ministerpräsidenten. T-Online. Online. Retrieved 24.6.2022.

Benoit, K., Bräuninger, T., & Debus, M. (2009). Challenges for estimating policy preferences: Announcing an open access archive of political documents. German Politics 18(3): 440-453 (updated dataset).

Bräuninger, T., Debus, M. (2012). Parteienwettbewerb in den deutschen Bundesländern. 1st ed. Wiesbaden: VS, Verlag für Sozialwissenschaften.

dpa (2018). Doris von Sayn-Wittgenstein aus der AfD-Fraktion ausgeschlossen. ZEIT-Online. Online. Retrieved 24.6.2022.

dpa (2020). AfD verliert Fraktionsstatus in Kiel. ZEIT-Online. Online. Retrieved 24.6.2022.

Deutsche Fördermittelberatung (2022). GRW-Förderung. Online. Retrieved 24.6.2022.

Forschungsgruppe Wahlen. Wahlanalyse Schleswig-Holstein 2022. Online. Retrieved 10.8.2022.

Infratest dimap (2022a). Landtagswahl Schleswig-Holstein 2022. Kandidatenfaktor. Online. Retrieved 10.8.2022.

Infratest dimap (2022b). Landtagswahl Schleswig-Holstein 2022. Zufrieden mit Ministerpräsident/in vor der jeweils letzten Wahl. Online. Retrieved 10.8.2022.

Infratest dimap (2022c). Schleswig-Holstein TREND April II 2022.Politikerzufriedenheit. Online. Retrieved 10.8.2022.

Infratest dimap (2022d). Schleswig-Holstein TREND April 2022. Zufriedenheit mit der Landesregierung. Online. Retrieved 10.8.2022.

Infratest dimap (2022e). Landtagswahl Schleswig-Holstein 2022. Welches Thema spielt für Ihre Wahlentscheidung die größte Rolle? Online. Retrieved 10.8.2022.

Infratest dimap (2022f). Landtagswahl Schleswig-Holstein 2022. Gute wirtschaftliche Lage. Online. Retrieved 10.8.2022.

Infratest dimap (2022g). Wahlverhalten bei der Landtagswahl in Schleswig-Holstein am 08.Mai 2022 nach Alter. Online. Retrieved 10.8.2022.

Infratest dimap (2022h). Landtagswahl Schleswig-Holstein 2022. Große Unterstützung für Landespartei. Online. Retrieved 10.8.2022.

Infratest dimap (2022i). Landtagswahl Schleswig-Holstein 2022. Zufriedenheit mit der politischen Arbeit. Online. Retrieved 10.8.2022.

Infratest dimap (2022j). ARD-Deutschland Trend April 2022. Politikerzufriedenheit. Online. Retrieved 10.8.2022.

Infratest dimap (2022k). Landtagswahl Schleswig-Holstein 2022. Gute Koalition. Online. Retrieved 10.8.2022.

Laakso, M. & Taagepera, R. (1979). “”Effective” Number of Parties: A Measure with Application to West Europe”. Comparative Political Studies 12 (1): 3–27.

Müller, W. C. & Strøm, K. (1999). Policy, office, or votes ? How political parties in Western Europe make hard decisions. Cambridge/New York.

NDR/Infratest dimap (2022). Wichtigste Probleme in Schleswig-Holstein. Online. Retrieved 10.8.2022.

Sturm, R. (2013). Woran scheitern Länderkoalitionen? Eine theoriegeleitete empirische Analyse. In: Decker, F. & Jesse, E. (eds.). Die deutsche Koalitionsdemokratie vor der Bundestagswahl 2013. Parteiensystem und Regierungsbildung im internationalen Vergleich. Baden-Baden: 241-258.

ZDF PolitBarometer (2022). Bewertung der zehn wichtigsten Politiker/innen. Online. Retrieved 24.6.2022.

citer l'article

Oliver Drewes, Regional election in Schleswig-Holstein, 8 May 2022, Oct 2022,

à lire dans cette issue

voir toute la revue