Regional election in Sicily, 25 September 2022

Vincenzo Emanuele

Associate Professo at LUISS Gardo Carli UniversityIssue

Issue #3Auteurs

Vincenzo Emanuele

Issue 3, March 2023

Elections in Europe: 2022

Introduction

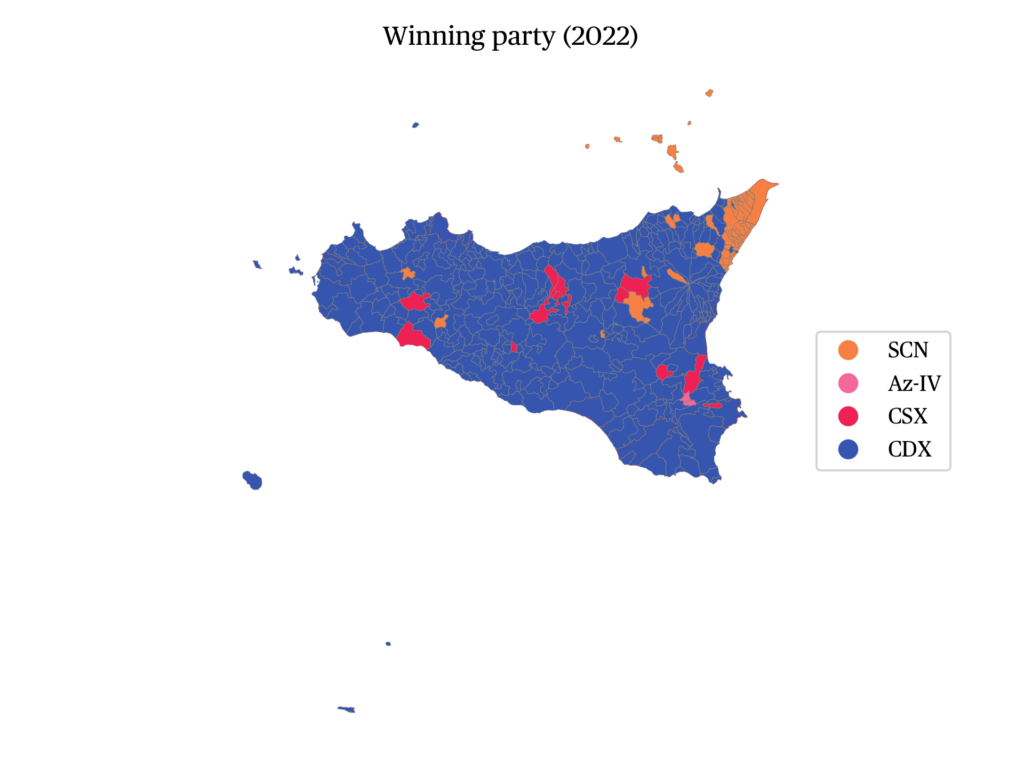

The center-right won the September 25 Sicilian regional election, its second victory in a row following its win in the 2017 ballot. Renato Schifani, former president of the Senate, is the new regional president and succeeds outgoing president Nello Musumeci, who did not run again due to internal conflicts within the center-right coalition (Adn Kronos, 2022). The vote was in many ways a confirmation of the historical determinants of Sicilian politics. Indeed, Sicily has always been characterized by a moderate and conservative vote (Nuvoli, 1989; Raniolo, 2010). Christian Democracy has dominated the Island’s politics for 45 years; following the Tangentopoli affairs in the 1990s, Sicily became the Eden of Berlusconiism. During the so-called ‘Second Republic,’ that is, since 1994, the center-right has always won regional elections, with the only exception of 2012. In that one case, the defeat was mainly caused by internal divisions within the conservative camp: the center-right was in fact divided between Musumeci (who would later win in 2017) and Micciché (the historic regional leader of Forza Italia); the center-left, strengthened by the entry in the coalition of the Union of the Center (UDC), a post-democratic party coming from the center-right, took advantage of these divisions to conquer Palazzo d’Orleans for the first time under Rosario Crocetta’s leadership. This victory, however, was no sign of a sudden shift to the left of the Sicilian electorate. Crocetta collected 30.5 percent of the valid votes, corresponding to just 13.3 percent of the electoral body. In 2017, the center-right ran united again, from the UDC to Fratelli d’Italia (FDI), and the challenge between the two traditional poles of Italian politics ended with a clear victory for the center-right. In the September 25 elections, this scenario was repeated. The Italian parliamentary elections held on the same day saw the victory of the center-right led by FDI leader Giorgia Meloni, only consolidating the coalition’s overwhelming victory in the Island. Schifani’s victory was clear-cut, albeit in the context of a voter turnout of less than half the eligible voters, despite the potential for mobilization resulting from the simultaneous presence of the general elections. The Forza Italia candidate came in well ahead of his rivals, Caterina Chinnici of the center-left and Nunzio di Paola of the Five Star Movement (M5S). Both, moreover, were clearly outperformed by an outsider candidate, former Messina Mayor Cateno De Luca, who emerged as the main newcomer in these elections, coming in second with 24 percent of the vote.

This paper is structured as follows: in the next section, we will analyze the regional electoral environment on the eve of the vote, briefly describing the characteristics of the regional electoral law and the configuration of the political supply side; the next section is devoted to the analysis of the vote, focusing on three aspects: electoral participation, voting in the majoritarian competition, i.e., voting for presidential candidates, and proportional competition, i.e., voting for party lists.

The context: election law and configuration of the political supply side

The regional election is governed by Regional Law No. 7/2005. The voter has two votes, one for a presidential candidate and one for a list of candidates to be elected to the Regional Assembly (ARS). The competition for president is a classic plurality or first-past-the-post system: there is a single round of voting, and the candidate who gets a relative majority of votes is elected president. In the competition for the regional parliament, on the other hand, a mixed system applies. Of the 70 deputies to be elected to the ARS, 62 are elected by a proportional system on the basis of lists competing in the nine provincial constituencies. 1 Seats are distributed to lists that have exceeded 5 percent at the regional level, using the Hare quotient method with highest remainders (Emanuele 2013). Voters vote for a list and can cast a preference vote for a candidate from that list. In addition, ‘disjunctive voting’ is possible, that is, voters can choose a presidential candidate and a list not supporting that presidential candidate. Of the remaining eight seats, two go to the newly elected president and the second-place presidential candidate, respectively. The remaining six seats constitute the so-called ‘list’ of the President, i.e., an electoral bonus that, under certain conditions, 2 is awarded to the winning coalition to facilitate the emergence of a parliamentary majority. The Sicilian electoral law is ultimately a non-majority-assuring law (Emanuele, 2013: 40), that is, it does not guarantee a majority of seats to the winning coalitions. There have been five regional elections since the introduction of this system. In one case, in 2012, the winning president (Crocetta) did not obtain an absolute majority, while in another case, in 2017, that majority was of only one seat, that of the president himself (Emanuele & Riggio, 2018a: 255). These characteristics produce clear incentives towards bipolarization and the formation of broad coalitions (to obtain a majority through the bonus seats), while pushing parties to contain intra-coalition fragmentation by reducing the number of competing lists (to make sure that they exceed the 5 percent threshold at the regional level).

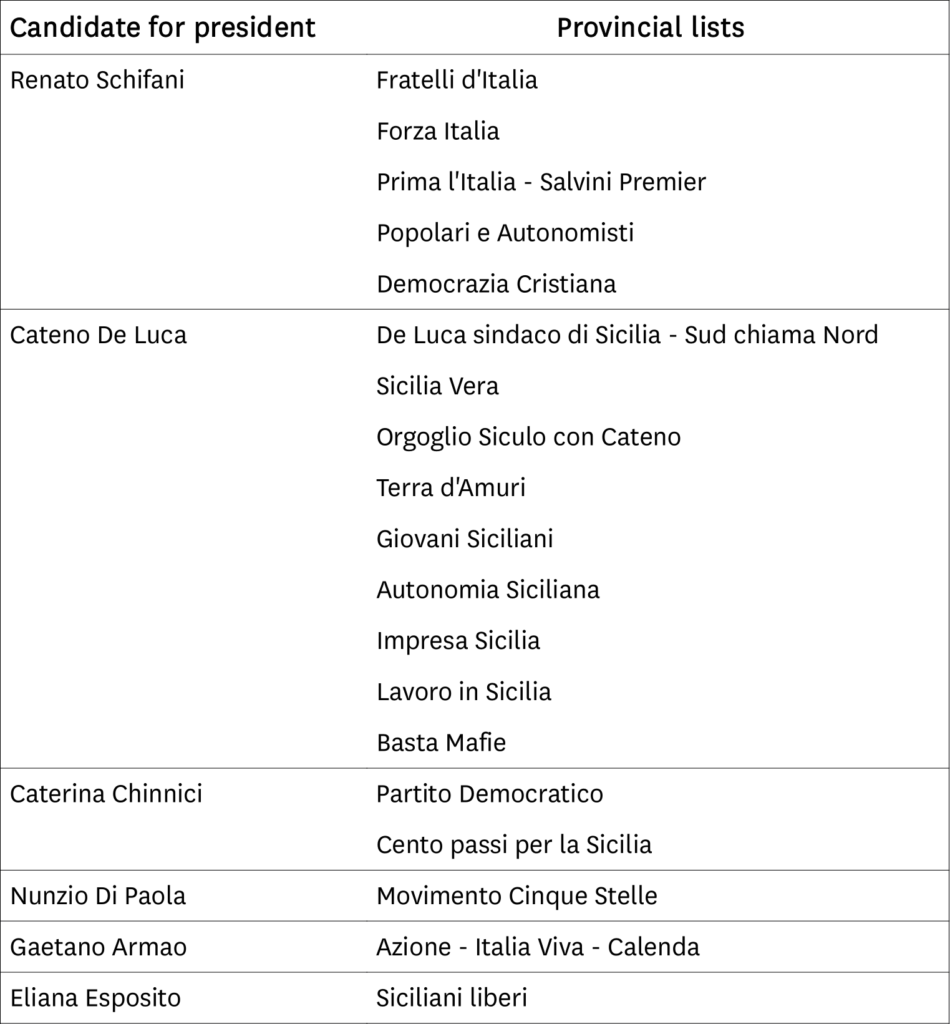

As in 2017, the center-right (Cerruto & La Bella, 2018: 41) seems to have fully understood the characteristics of the electoral system, and fields a united and unfragmented coalition to maximize institutional incentives. The coalition led by Renato Schifani is composed of five lists (see Figure a). The three political forces that make up the coalition at the national level (FDI, Forza Italia and the League, here called Prima l’Italia — Salvini Premier) are joined by two regional lists representing, respectively, the two former Presidents of the Region, Raffaele Lombardo (the Popolari e Autonomisti list) and Salvatore Cuffaro (the Democrazia Cristiana list). 3 This coalitional arrangement, which enabled the center-right to win the Palermo municipal elections by a large margin in June 2022, is being implemented again at the regional level.

The center-left, on the other hand, presents only two lists (in 2017 there were four) in support of Caterina Chinnici (a magistrate and daughter of Judge Rocco Chinnici, who was killed by the Mafia in 1983): that of the Democratic Party (PD) and Cento Passi per la Sicilia, the list of Claudio Fava, a former radical leftist candidate in 2017 and at the time able to pass the 5 percent bar on his own. Even before the vote, the competition between the two coalitions appears decidedly unbalanced in favor of the center-right, which, as noted above, has never lost a regional election when it has stood united on the ballot. In addition, the center-left was unable to secure the support of either the so-called ‘Third Pole,’ that is, the Azione and Italia Viva list, or the M5S, which in 2017, while running alone under Giancarlo Cancelleri’s leadership, had come close to a resounding success, achieving 34.7 percent and almost overtaking the center-left candidate. The Third Pole decided to run alone behind the candidacy of the former budget councillor of the Musumeci government, Gaetano Armao, while the M5S, after participating in the center-left primaries that had decreed Chinnici’s victory, pulled out of the coalitional agreement and preferred to run on its own with the candidacy of the Five-Star MP Nunzio Di Paola.

Beyond these coalition dynamics, the gap between the center-right and center-left appeared unbridgeable in the run-up to the election by virtue of another fact. An army of 350 ARS candidates (70 from each of the five lists) supported Schifani’s candidacy, against only 140 from the center-left. This disproportion is made all the more significant by a number of transitions of 2017 ‘Lords of Preferences’ 4 (Emanuele & Marino, 2016) from the center-left to the center-right. We highlight two of them in particular: in Palermo, preference boss Edy Tamajo (13984 votes in 2017) moves from Sicilia Futura (a list of the center-left coalition) to Forza Italia; in Catania, preference recordman Luca Sammartino (32492 votes in 2017, accounting for 7.3 percent of the list vote in the province of Catania, see Emanuele & Riggio, 2018: 290) moves from the PD to the League. The vote in Sicily, as in Southern Italy in general, has always been extremely candidate-oriented (Fabrizio & Feltrin, 2007) with both a highly volatile party vote and stable links between candidates and their voter packs (Raniolo, 2010; Emanuele & Marino, 2016). Thus, it is a vote given to the person before the party, and not exempt from clientelistic and vote-buying dynamics (Parisi & Pasquino, 1977; D’Amico, 1993; Raniolo, 2010). Winning the support of Lords of Preferences is therefore key for presidential candidates, especially in a context of low expected turnout, where vote packages controlled by local figures acquire even greater overall weight (Emanuele & Marino, 2016; Emanuele & Riggio, 2018b).

Finally, the electoral supply side is rounded out by the civic candidacy of Eliana Esposito with the Siciliani Liberi list (already running in 2017 with Roberto La Rosa, 0.7 percent) and, most importantly, by Cateno De Luca’s candidacy. The former mayor of Messina, building on almost unanimous support from the Peloritan city, presents himself as an outsider in the competition, with the intention of attracting the protest vote from both left and right. He enjoys the support of as many as nine lists, although only two (Sud chiama Nord and Sicilia Vera) are present throughout the region (see note of Figure a).

The results

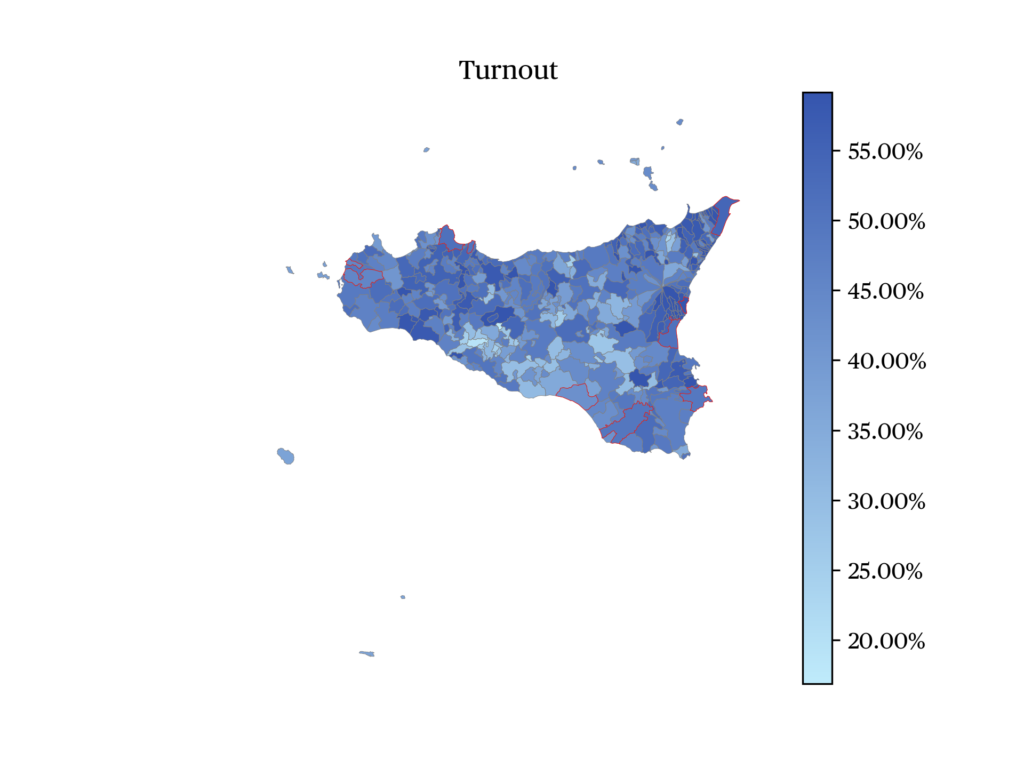

Voter turnout, which has always been significantly lower than in general elections (Riggio, 2018: 230), was around or just above 60 percent until 2008. In 2008, as in 2022, the regional election were held on the same day as the general elections. As a result, between 2008 and 2012, turnout collapsed by almost 20 percentage points, falling below 50 percent for the first time in any Italian regional election (D’Alimonte 2013). Over the past 10 years, the trend has not shown significant reversals: in 2017, turnout dropped further, albeit slightly, to 46.8 percent. In 2022, it rose again by two points, to 48.8 percent, very little if we consider the potential pull provided by the simultaneous general elections. Between 2008 and 2022, about 18 percentage points of turnout (more than 800,000 votes) have been lost. Fewer than one in two Sicilians went to the polls, and the most popular presidential candidate, Schifani, received less than 900,000 votes, corresponding to less than 20 percent of the Island’s voters. To understand the magnitude of the phenomenon, one needs only consider that in 2008 the most voted presidential candidate, Lombardo, had obtained more than twice as many votes, more than 1.8 million. Looking at the distribution of turnout by province (see also Figure c), participation exceeded the absolute majority of eligible voters only in Messina (53.6 percent), probably dragged by Cateno De Luca’s electoral boom, as well as Catania and Palermo (52.2 percent and 50.2 percent respectively). By contrast, the lowest turnout was recorded in Enna (40 percent), an inland province that has a comparatively more peripheral electorate from a socio-economic point of view and already set a negative voting participation record among the island’s provinces in 2017.

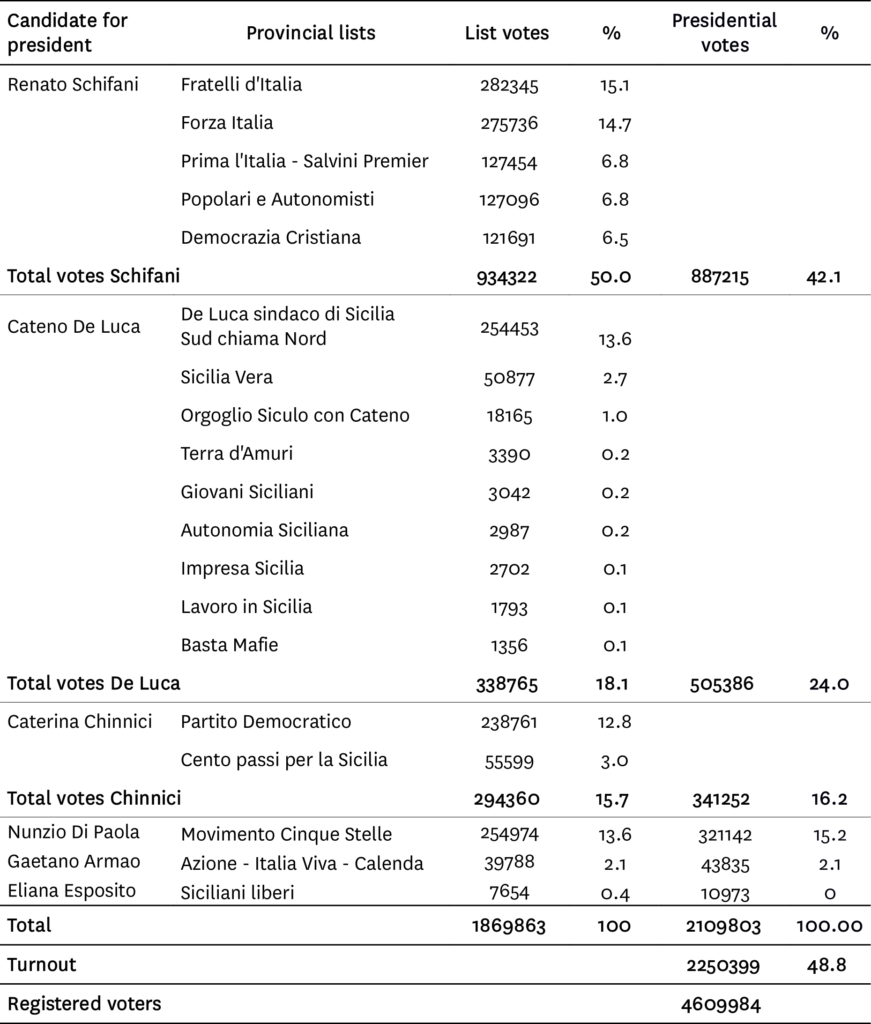

Turning to the results, Figure b shows the regional summary of the presidential ballot.

As mentioned above, Cateno De Luca’s electoral success constituted the main novelty of the 2022 regional election. With 24 percent, the former mayor of Messina clearly outperformed his center-left and M5S competitors. In ‘his’ province of Messina, he obtained an absolute majority of the vote and, with 52.6 percent, overtook all his rivals including Schifani. His success affected the scores of all other parties, and especially of the M5S, which won 6.3 percent in the province of Messina (it had won 27.2 percent in 2017).

In all other provinces, Renato Schifani far outdistanced his competitors, obtaining more votes than the second and third candidates combined and more than 10 percentage points more than a potential center-left ‘wide field’ (a hypothetical coalition formed by the center-left and the M5S, which failed to emerge in the pre-electoral period after Caterina Chinnici won the primaries). Schifani gathered an absolute majority of the vote only in Agrigento, while in Messina he gather 29.2 percent of the vote.

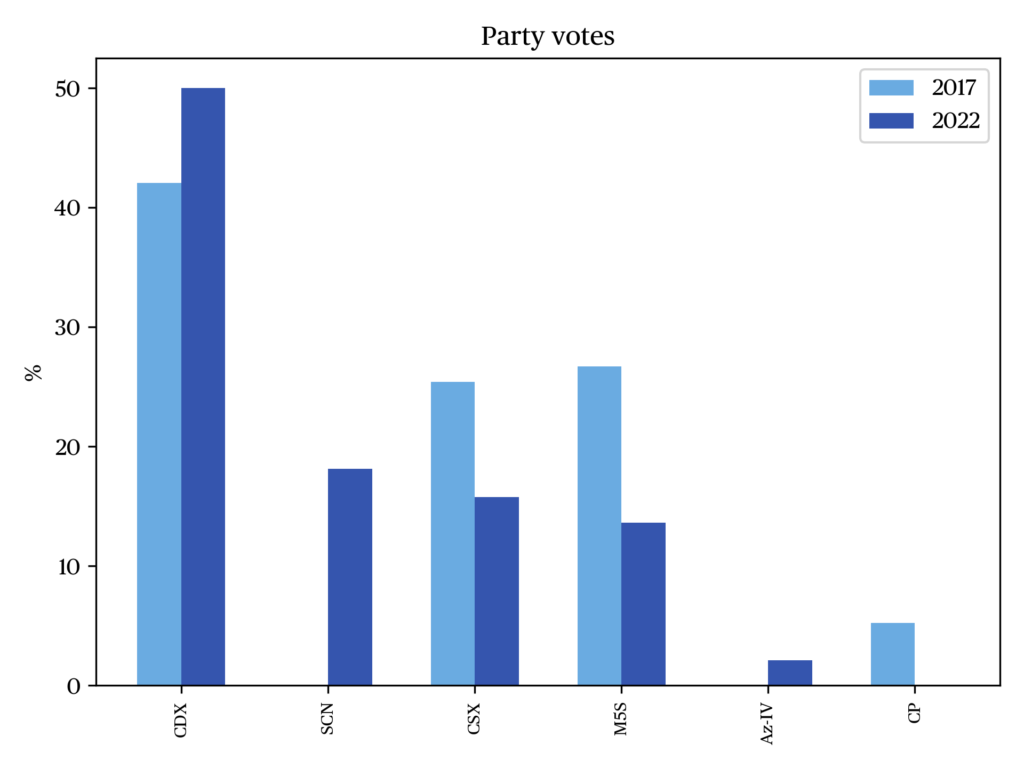

With 16.2 percent, the center-left coalition obtained its worst result ever at regional elections in Sicily: Caterina Chinnici took about 47,000 fewer votes than Fabrizio Micari, the candidate in 2017, and as many as 277,000 fewer than in 2012, when Rosario Crocetta won the election. The M5S did not perform better than the center-left: Nunzio Di Paola’s 15.2 percent is a meager result compared with Giancarlo Cancelleri’s 34.7 percent in 2017, and, even more, with the 27 percent obtained by the party in the general election on the same day. Finally, the Third Pole’s attempt to emerge as a new player in Sicilian politics failed: Gaetano Armao obtained just over 2 percent and the Azione-Italia Viva list did not gain any seats in the regional assembly (see also Figure d).

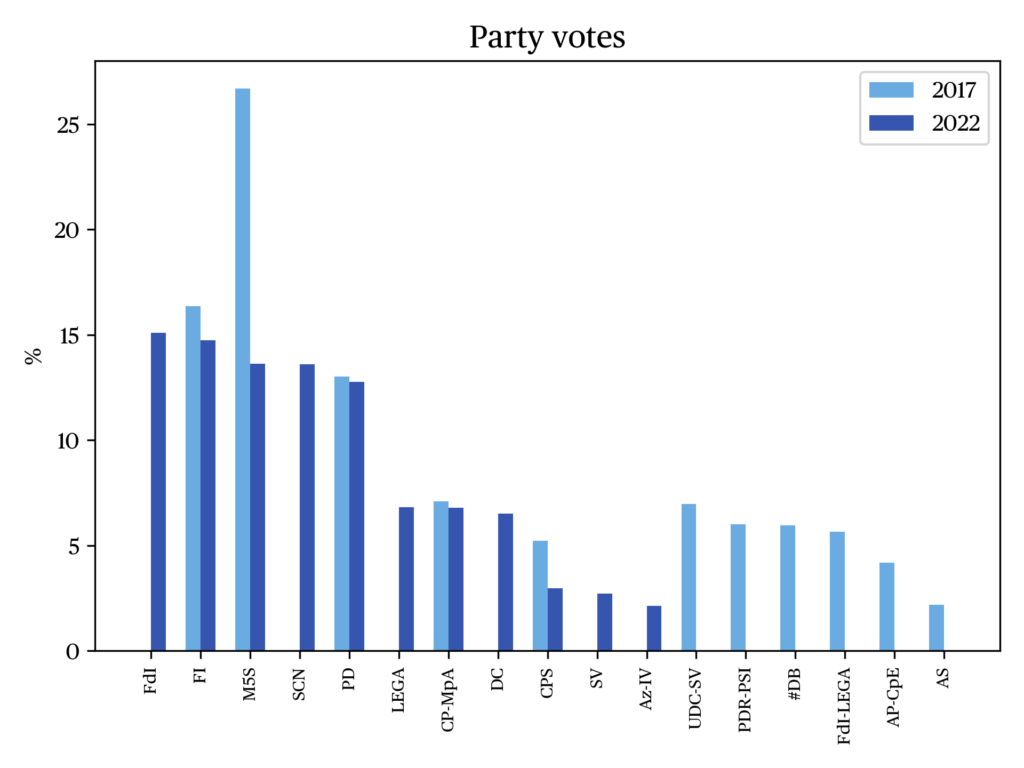

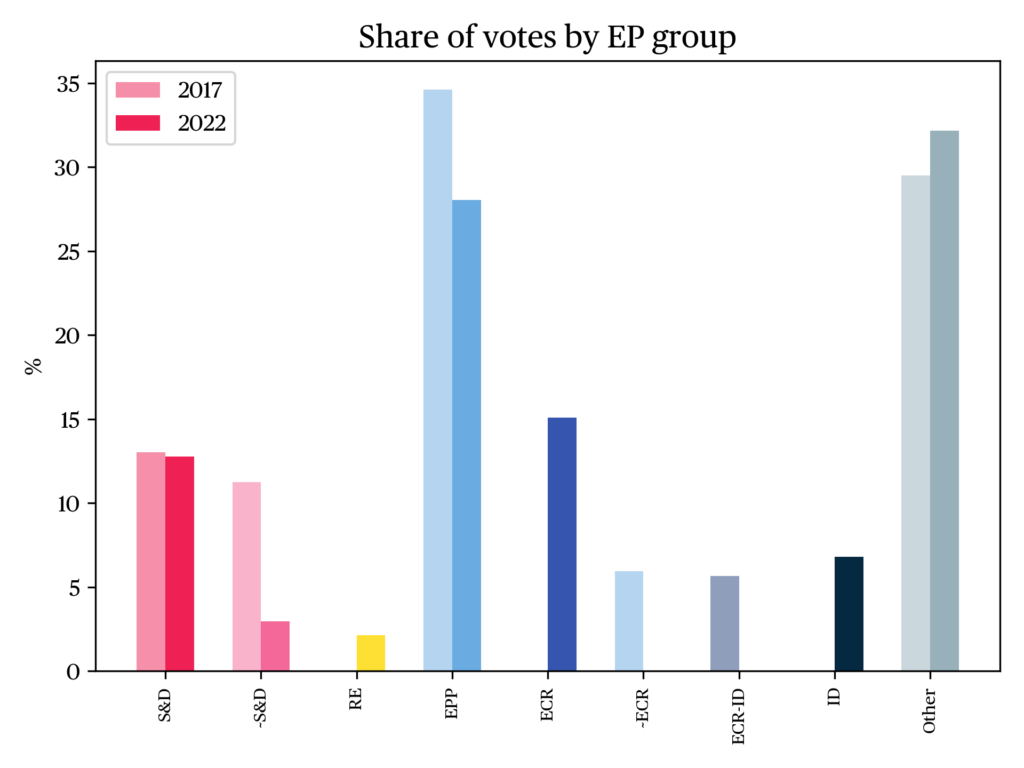

The results of the proportional vote (see panel “the data”) reveal the excellent ‘strategic coordination’ of the center-right coalition (Cox, 1997). The five lists supporting Schifani all manage to pass the 5 percent threshold and enter the ARS. Fratelli d’Italia emerges as the most voted party with 15.1 percent. Giorgia Meloni’s party takes advantage of a positive overall trend to achieve an exceptional growth compared to 2017, when it collected just 5.6 percent of the vote despite running on a single together with the League. The League, for its part, gains 6.8 percent of the vote. Giorgia Meloni’s party narrowly overtakes Forza Italia, which has declined slightly since 2017 when it led the coalition supporting Musumeci with 16.4 percent. The two post-Democratic lists supporting Lombardo and Cuffaro both pass the bar although they are down slightly from 2017.

Overall, the center-right forces rise from 42.1 percent in 2017 to 50 percent in 2022, and their result in the proportional contest are significantly better than in the presidential ballot, which uses a first-past-the-post system. Schifani, in fact, scores about eight percentage points less than his lists. The negative performance of the coalition in these respects is nothing new for the center-right (Emanuele & Riggio, 2018a: 251) and once again confirms the decisive role played by the Lords of Preferences in shaping the electoral outcome: suffice it to say that the aforementioned Edy Tamajo, who run for member of the regional assembly in the province of Palermo in the ranks of Forza Italia after being elected in 2017 with the center-left, obtained 21,700 votes (or 4.8 percent) for his provincial list. The same percentage was obtained by Luca Sammartino, a former PD member and candidate for the province of Catania (21,011 votes).

The other side of the personal vote, i.e., the vote given to the presidential candidate alone, went almost entirely to Cateno De Luca, who was able to get about six points more than his lists, among which only Sud chiama Nord surpasses the bar, becoming one of the main parties on the island. 5 In the ranks of the opposition, while, as anticipated, the Azione-Italia Viva list remained well below the threshold, the performances of the PD and M5S were very disappointing: the former won only 12.8 percent of the vote, making it only the fifth party in the region while in 2017 it came in second (albeit with a barely higher percentage, 13 percent); the latter, with 13.6 percent, has faced tough competition from De Luca when trying to attract protest votes and has eventually halved its 2017 performance, when it was the region’s leading party with 26.7 percent. Finally, Claudio Fava’s Cento passi per la Sicilia list stays out of the ARS, dropping from 5.2% in 2017 to 3% in 2022.

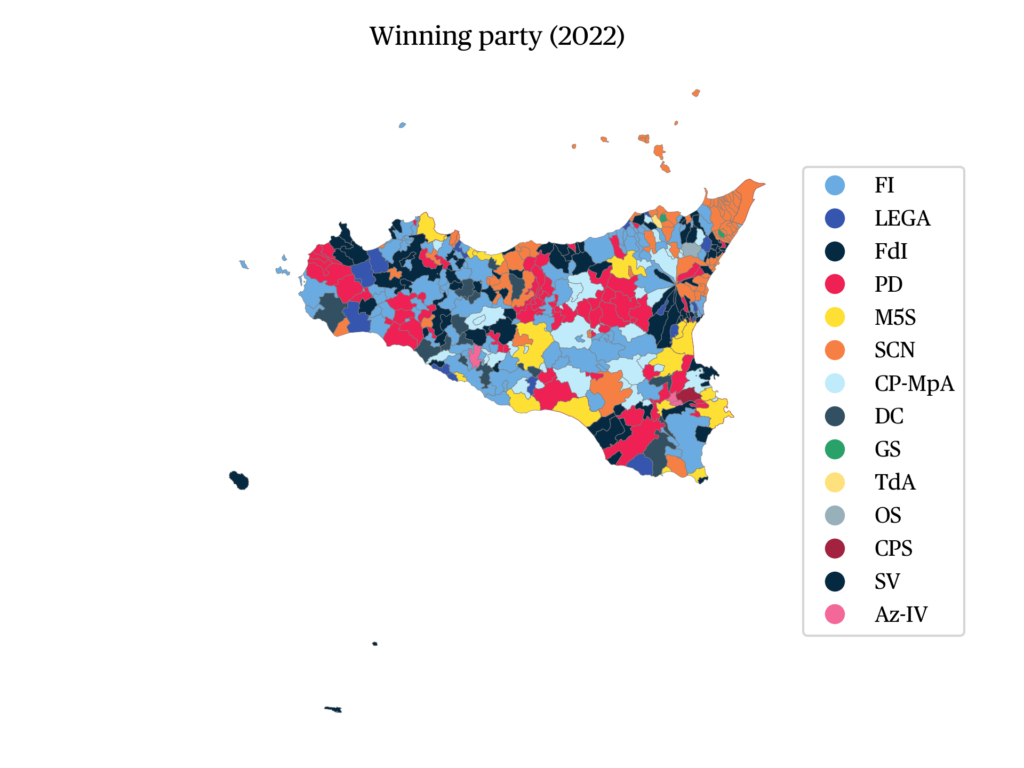

Regarding the territorial distribution of support (see also panel “the data”), Forza Italia is the most voted party in Agrigento (14.5 percent), Caltanissetta (20.7 percent) and Palermo (17.2 percent), while FDI is first only in Catania (16.8 percent) and Ragusa (19.3 percent). Sud Chiama Nord is the most voted party in the province of Messina with 25.4 percent, while PD prevails in Enna (24.1 percent) and Trapani (16.2 percent) and M5S is the list with the highest support in Syracuse (15.7 percent).

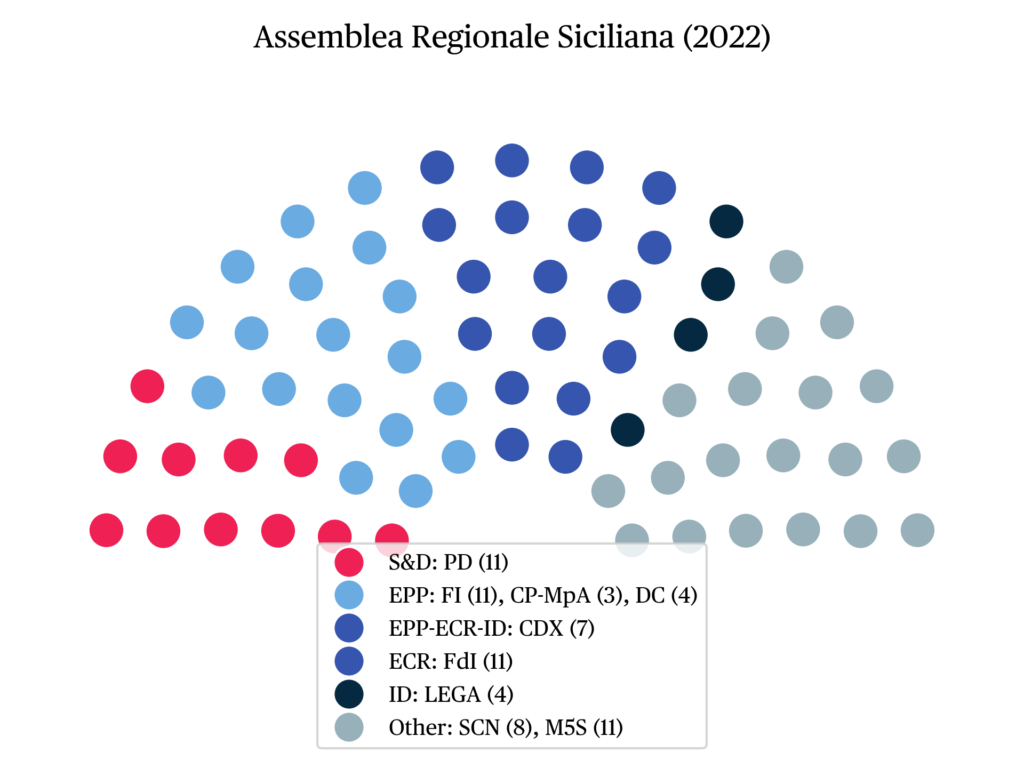

In view of these results, Schifani secures a solid majority in the Council with 40 out of 70 deputies (including President Schifani’s own seat). FDI and Forza Italia lead the majority with 13 deputies each, followed by the League and DC with five and the Popolari e Autonomisti list with four. In the ranks of the opposition, only three lists enter the ARS: the PD and M5S with 11 seats and Sud chiama Nord with 8 seats. 6

Following this clear victory, the center-right’s dominance of Sicilian regional politics will continue for the next five years, and, what is more, will be able to rely on the advantage of benefiting from a ‘friendly’ government in Rome, led by Prime Minister Giorgia Meloni.

References

Adn Kronos (2022, 10 August). Elezioni regionali Sicilia, Musumeci non si candida: “Sono presidente scomodo”.

Cerruto, M. & La Bella, M. (2018). Le elezioni regionali in Sicilia del 5 novembre 2017. Quaderni dell’Osservatorio elettorale QOE-IJES, 80(2): 29-82.

Cox, G. W. (1997). Making votes count: strategic coordination in the world’s electoral systems. Cambridge University Press.

D’Alimonte, R. (2013). L’ombra dell’ingovernabilità. In De Sio, L. & Emanuele, V. (eds.), Un anno di elezioni verso le Politiche 2013, Dossier CISE 3, Roma: Centro Italiano Studi Elettorali: 53-54.

D’Amico, R. (1993). La “cultura elettorale” dei siciliani. In Morisi M. (ed.), Far politica in Sicilia. Deferenza, consenso e protesta, Milano: Feltrinelli: 211-257.

Emanuele, V. (2013). Regionali 2012 in Sicilia: come funziona il sistema elettorale. In De Sio, L. & Emanuele, V. (ed.). Un anno di elezioni verso le Politiche 2013, Dossier CISE 3, Roma: Centro Italiano Studi Elettorali: 39-41.

Emanuele, V. & Marino, B. (2016). Follow the candidates, not the parties? Personal vote in a regional de-institutionalised party system. Regional and Federal Studies, 26(4): 531-554.

Emanuele, V. & Riggio, A. (2018a). Disgiunto e utile: il voto in Sicilia e la vittoria di Musumeci. In Emanuele, V. & Paparo, A. (ed.). Dall’Europa alla Sicilia. Elezioni e opinione pubblica nel 2017, Dossier CISE (10), Roma: Centro Italiano Studi Elettorali: 251-255.

Emanuele, V. & Riggio, A. (2018b). L’altra faccia del voto in Sicilia: il consenso ai Signori delle preferenze fra ricandidature ed endorsement. In Emanuele, V. & Paparo, A. (eds.), Dall’Europa alla Sicilia. Elezioni e opinione pubblica nel 2017, Dossier CISE (10), Roma: Centro Italiano Studi Elettorali: 283-295.

Fabrizio, D. & Feltrin, P. (2007). L’uso del voto di preferenza: una crescita continua. In Chiaramonte, A. & Tarli Barbieri, G. (ed.), Riforme istituzionali e rappresentanza politica nelle regioni italiane, Bologna: Il Mulino: 175-199.

Nuvoli, P. (1989). Il dualismo elettorale Nord-Sud in Italia: persistenza o progressiva riduzione? Quaderni dell’Osservatorio Elettorale, 23: 67-110.

Parisi, A. & Pasquino, G. (eds.) (1977). Continuità e mutamento elettorale in Italia. Bologna: Il Mulino.

Raniolo, F. (2010). Tra dualismo e frammentazione. Il Sud nel ciclo elettorale 1994-2008. In D’Alimonte R., & Chiaramonte, A. (eds.), Proporzionale se vi pare. Le elezioni politiche del 2008, Bologna: Il Mulino: 129-171.

Riggio, A. (2018). Il Gattopardo in laboratorio: la Sicilia al voto. In Emanuele, V. & Paparo, A. (eds.), Dall’Europa alla Sicilia. Elezioni e opinione pubblica nel 2017, Dossier CISE (10), Roma: Centro Italiano Studi Elettorali: 229-233.

Notes

- The distribution is as follows: Palermo 16 seats, Catania 13, Messina 8, Agrigento 6, Syracuse and Trapani 5, Ragusa 4, Caltanissetta 3 and Enna 2.

- The bonus is not awarded if the coalition of the president-elect won at least 42 seats in the proportional contest (60 percent of the ARS seats). In this case, the six seats are redistributed among minority lists that have exceeded the 5 percent threshold.

- The two former presidents have returned to politics after years of judicial affairs: Lombardo was convicted in first instance for outside participation in a mafia association in 2014 and vote-buying in 2017, and later acquitted of both charges in the second appeal trial; Cuffaro, on the other hand, returned to freedom in 2015 after serving a seven-year sentence for aiding and abetting the mafia.

- to highly influential local leaders whose political choices affect their constituents’ voting behavior (called preferenze, “preferences,” in Italian).

- At the same time, the success of Sud chiama Nord also extended to the general election: candidates in the House and Senate uninominal constituencies for the province of Messina in fact elected two representatives from De Luca’s list.

- At the time of writing, the number of seats collected by each list is not currently official, since the final results of 48 electoral sections remain to be determined.

citer l'article

Vincenzo Emanuele, Regional election in Sicily, 25 September 2022, Mar 2023, 114-120.

à lire dans cette issue

voir toute la revue