Regional election in Styria, 24 November 2024

Franz Fallend

Researcher at the University of SalzburgIssue

Issue #5Auteurs

Franz Fallend

Issue 5, January 2025

Elections in Europe: 2024

Introduction

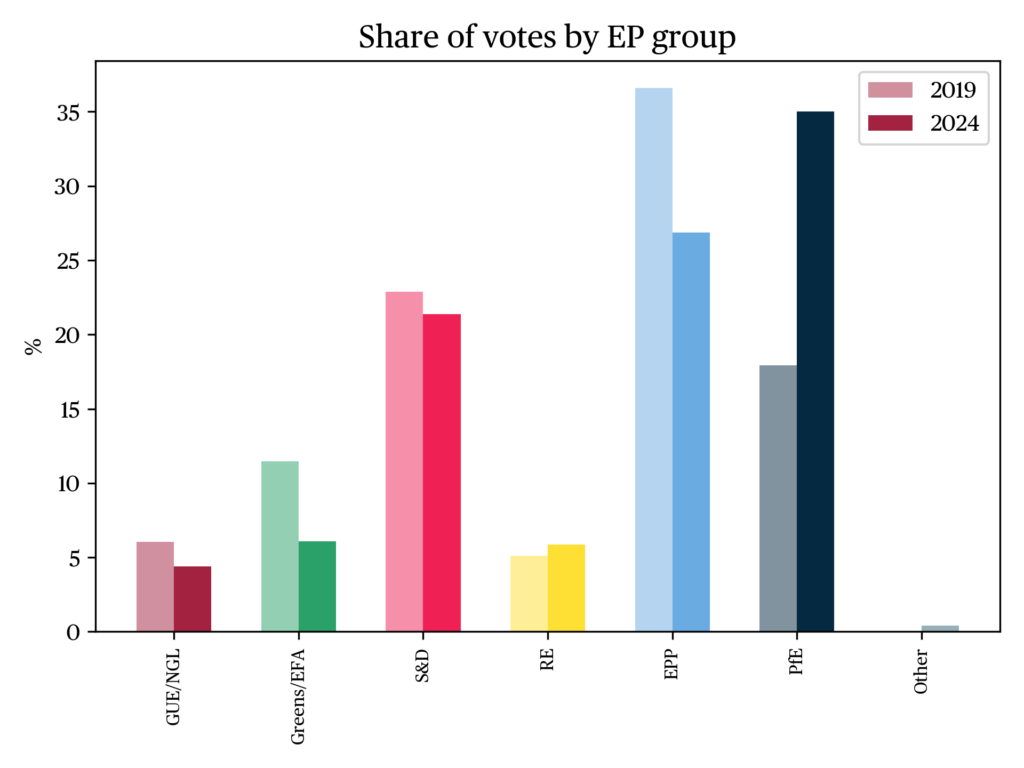

The elections for the state parliament (Landtag) of Styria on 24 November 2024 radically changed the political landscape in Austria. Once dominant in the region, the conservative Austrian People’s Party (ÖVP, EPP), dramatically lost votes and was ousted from first place. For the first time in history, the right-wing populist Freedom Party of Austria (FPÖ, PfE) won the election in this state and seized the position of state governor (Landeshauptmann). The Social Democratic Party of Austria (SPÖ, S&D), which had participated in all state governments since 1945, only came in third and had to watch from the sidelines when a new state government (Landesregierung) was formed between the FPÖ and ÖVP. The state parliament was completed by representatives of the Greens (Grüne, Greens/EFA), the Communist Party of Austria (KPÖ, GUE/NGL) and the liberal party New Austria (NEOS, Renew), all of which won only a few seats.

Political background

In the years up to 2022–2023, the ÖVP had dominated the party landscape in Austria. Sebastian Kurz, who was elected federal party chairman and became chancellor in 2017, moved the party to the right, above all by embracing a more restrictive asylum and immigration policy (FES, 2017). Taking advantage from Kurz’ popularity, the ÖVP was able to attract many former FPÖ voters in the federal elections of 2017 and 2019. Kurz formed a coalition government with the FPÖ, which in 2019 was brought down by the so-called “Ibiza scandal”, which exposed the FPÖ federal party chairman Heinz-Christian Strache’s proclivity to corruption, illegal party financing and control of the media (Karner, 2021).

The setback for the FPÖ was short-lived, however. The COVID crisis, which the new federal government of the ÖVP and Greens tried to fight using freedom-restricting measures, and the Ukraine war, which triggered an energy and inflation crisis, stirred up civil unrest. The new FPÖ party chairman Herbert Kickl seized the opportunity to blame the governing parties for their failure to cope with the multiple crises. Since late 2022, the party had constantly stood at the forefront in opinion polls. This development culminated in 2024, when the FPÖ, for the first time in history, won both the elections to the European Parliament on 9 June (with 25.4% of the votes) and to the Austrian national parliament, the Nationalrat, on 29 September (with 28.8% of the votes).

The political trend at the national level was mirrored at the state level. In all recent state elections (in Tyrol in 2022, in Lower Austria, Carinthia and Salzburg in 2023, in Vorarlberg in 2024), the respective leading party, mostly the ÖVP, had lost between 5 and 10 percentage points, while the FPÖ had made strong gains (+14.1 points in Vorarlberg, the latest region to vote before Styria).

In post-1945 Styria, politics has been characterized by the ÖVP’s dominance and a high degree of political stability. Until 2005, the ÖVP won a majority of votes in all state elections and provided the state governor. The situation started to change somewhat when, in 2005, 2010 and 2015, the SPÖ crossed the finish line first. In 2005 and 2010, the Social Democrats also conquered the position of state governor. In 2015, both parties lost heavily, above all due to an unpopular reform in which small municipalities were merged into bigger entities. As a consequence, the SPÖ handed the governorship back to the ÖVP.

This stability has been promoted by the fact that, until the elections of 2015, the state constitution had prescribed a so-called proportional government, meaning that all major parties were automatically assigned seats in the state government after each election to the state parliament according to their share of seats. As a result, all state governments after 1945 included both ÖVP and SPÖ members, while the FPÖ as third-strongest party was permanently represented only since 1991. In 2011, however, growing in-fighting within government resulted in a constitutional amendment which replaced the system of proportional government by a system of free, majority-based coalition-building (Fallend, 2015, pp. 285–287). After the state elections in 2015, when the new system came into effect, as well as in 2019, the ÖVP and SPÖ agreed to form coalitions, referring the FPÖ and other parties to the opposition benches.

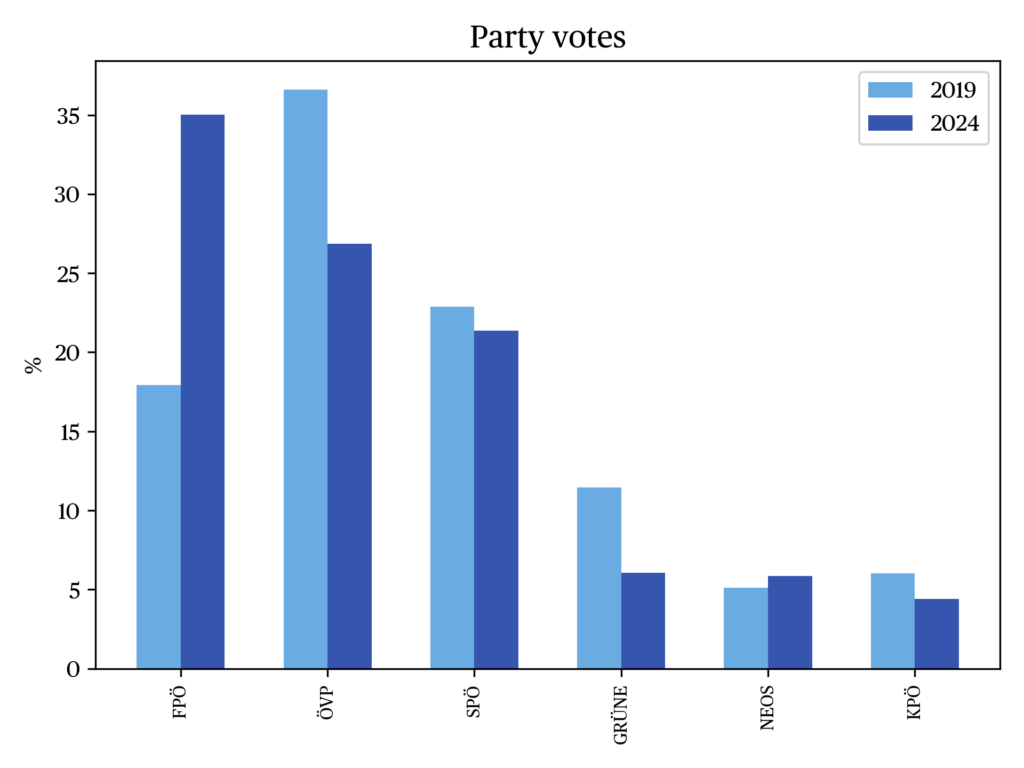

The elections of 2019 were called out before the 5-year legislative period ended regularly, as the ÖVP sought to benefit from the popularity of its federal party chairman and chancellor, Sebastian Kurz, at that time. The strategic manoeuvre turned out to be successful: the ÖVP was able to increase its share of the vote, compared to the previous election in 2015, by 7.6 percentage points (to 36.1%), while the SPÖ fell by 6.3 points (to 23%) and the FPÖ by 9.3 points (to 17.5%).

That the ÖVP would almost certainly not be able to repeat this victory in the next elections in 2024, was predicted by political observers long before election day. In 2022, State Governor Hermann Schützenhöfer resigned. He was replaced by his party colleague Christopher Drexler, who, in contrast to his mentor, was described in the media as being too intellectual and out of touch with the common people (Der Standard, 2022). Opinion polls at the beginning of 2024 indicated that despite a major scandal, in which the FPÖ party organization in the state capital of Graz was accused of having embezzled state party subsidies, the FPÖ was predicted to win. Surprisingly, this scandal seemed not to hurt the party, for which the fight against corruption (albeit, of the other parties) had always been a core campaign issue (Der Standard, 2024a). At that time, 49% of the people thought that the state was developing in the wrong direction; in 2019 only 20% had thought so (Der Standard, 2024b).

Election campaigns

In their election campaigns, both State Governor Christopher Drexler (ÖVP) and his Vice-Governor Anton Lang (SPÖ) stressed that they would prefer to continue their governing partnership after election day. Widely ignoring the opinion polls mentioned above, they regarded their past performance as success. At the same time, however, they were careful not to rule out a coalition with the FPÖ, hinting at the generally more constructive inter-party relations in Styria, compared to the federal level, and the ‘moderate’ position of the FPÖ state party chairman Mario Kunasek, compared to his more ‘radical’ federal party chairman Herbert Kickl. In fact, Kunasek also emphasized that his party was placed in the ‘middle of society’.

The election campaigns of the parties and the public debate were dominated by national rather than regional issues. In the media, the ÖVP and SPÖ campaigns were criticized as not sufficiently addressing the concerns of common people, like the rising living costs. The FPÖ made the fight against inflation one of its major issues and rejected costly climate policy measures (‘Styria remains a car land’ ran one of its slogans). A more restrictive asylum and immigration policy also played a prominent role in the FPÖ campaign. The party put up posters with an airplane and the slogan ‘Radical. Criminal. Take off!’. In a similar vein, the ÖVP top candidate supported a ban on headscarfs for Muslim pupils, and the SPÖ top candidate urged immigrants not willing to integrate into Austrian society to leave the country. Only rarely was it mentioned that the state competences in all these areas are limited.

One of the main issues of regional significance concerned the project to build a central hospital in Liezen, a town in the north-west of Styria, and to close a few smaller hospitals nearby for it. While the two governing parties, based on expert assessments, supported the project, all opposition parties, including the FPÖ, rejected it, warning of a deterioration of health care and high costs (ORF, 2024a).

The Greens, not surprisingly, put climate and environmental protection at the centre of their campaign. However, they had a hard time getting attention given the prevailing economic and social problems. The Communists, who since 2021 hold the office of mayor in Graz, focused on affordable housing. It was doubtful whether this issue was suitable to attract voters outside the state capital, however. Finally, the NEOS campaigned for less bureaucracy to improve the competitiveness of Styrian companies, for reforms in education, health and child care, and against patronage in the public sector (ORF, 2024b).

The national elections on 29 September also influenced the state elections in Styria. The FPÖ won 28.8% of the votes, the ÖVP 26.3% and the SPÖ 21.1%. As all other parties had ruled out a coalition with the FPÖ, Federal President Alexander Van der Bellen formally assigned the task to form a government not, as usual, to the leader of the strongest party, but to ÖVP party chairman and Federal Chancellor Karl Nehammer. Nehammer started coalition negotiations with SPÖ and NEOS, which had received 9.1% of the votes (the Greens with 8.2% were excluded). Drexler and Lang were unhappy with this decision, which in their eyes violated a good democratic convention and might lead even more voters to turn to the FPÖ (Kurier, 2024).

Election results

The election results (see “the data”) turned out to be even more pronounced than opinion polls had predicted. Voter turnout rose from 63.5% in 2019 to 70.8% in 2024. The FPÖ won by a landslide, doubling its share of the votes from 17.5 to 34.8%. With its best election result after 1945, the party for the first time also came in first. By contrast, both the ÖVP, which lost 9.2 points and landed at only 26.8$ of the votes, and the SPÖ, which was relegated to the third place with only 21.4% (-1.7 points), suffered their worst results ever.

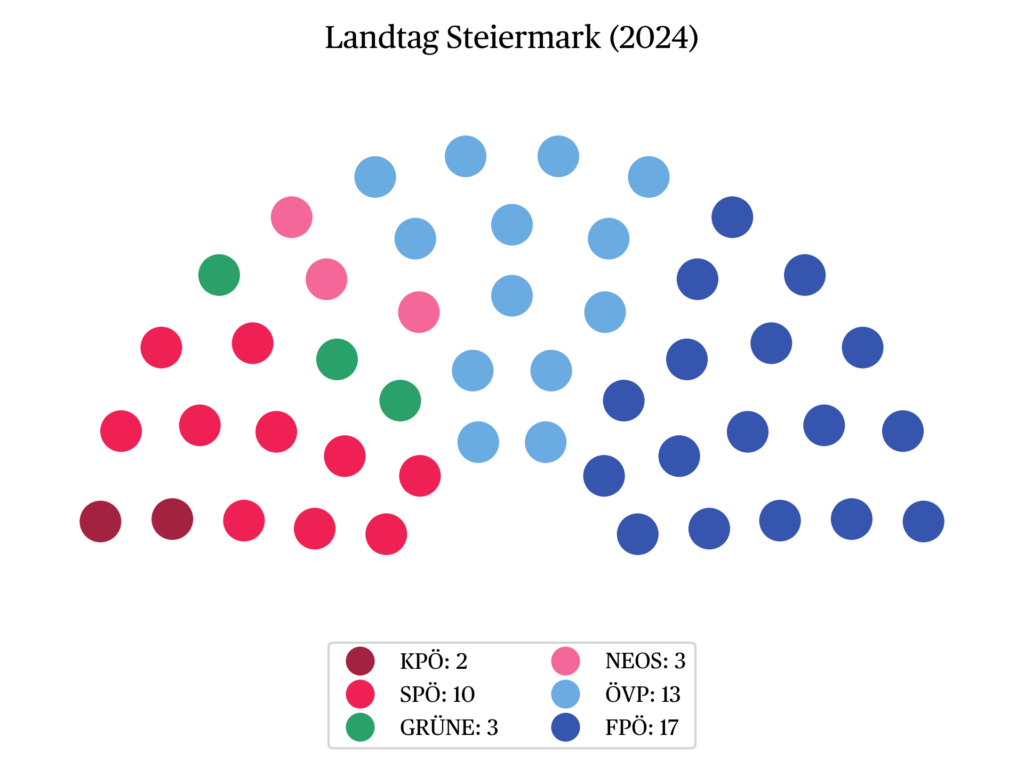

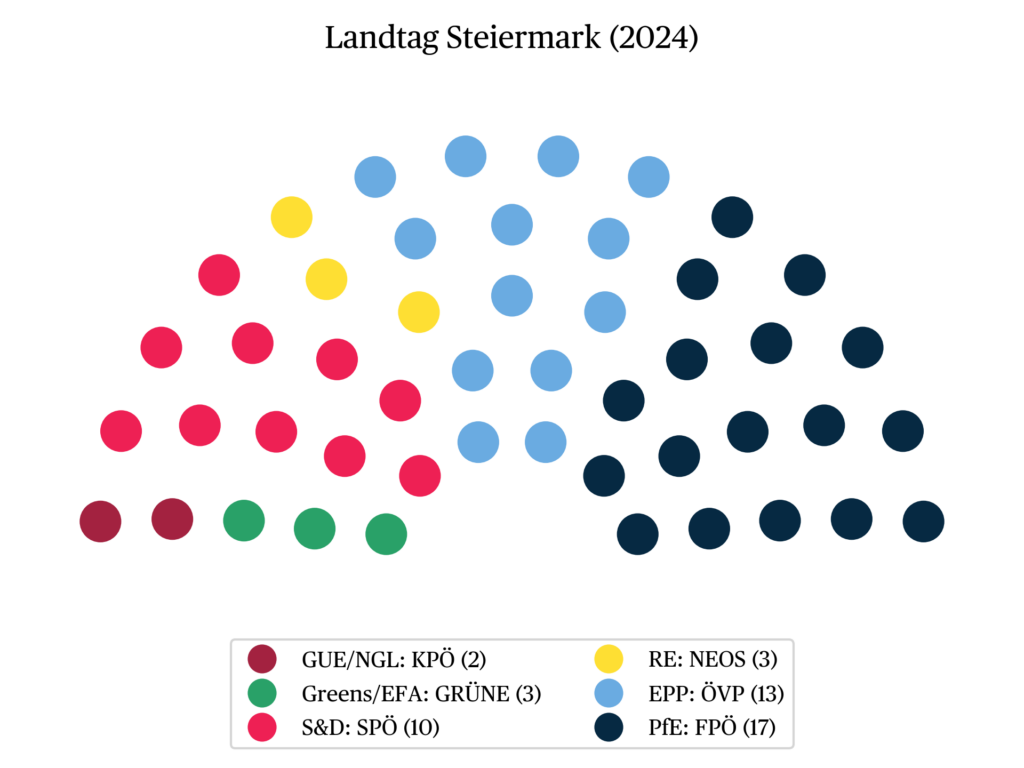

As a result, ÖVP and SPÖ also lost their government majority in parliament (together they only got 23 out of 48 seats), making their preferred option – a continuation of their partnership – unfeasible (Figure a).

ÖVP party chairman and State Governor Drexler blamed above all Federal President Van der Bellen for the victory of the FPÖ. He saw himself as a ‘sacrificed pawn’ (Bauernopfer) of the misguided decision of the president to bypass the FPÖ in the coalition negotiations at the federal level. Opinion pollsters, however, objected that the FPÖ had been leading the polls in Styria for a long time before the federal election, and that in particular FPÖ voters had made up their mind long before election day (Der Standard, 2024e). The media also reminded Drexler that from the start he was not a popular top candidate.

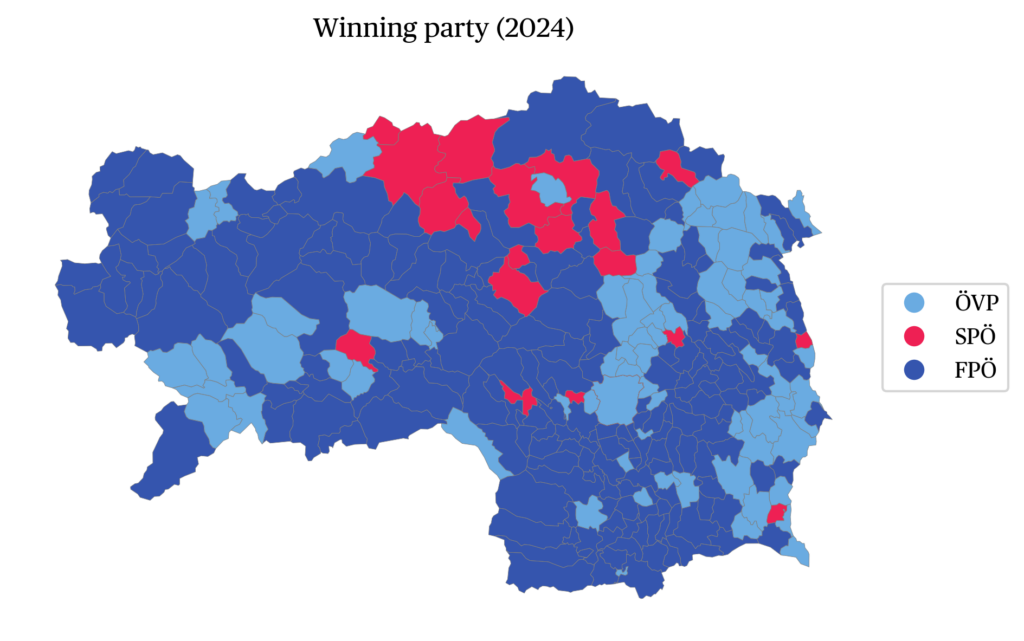

A look at the electoral map (see “the data”) shows that a major part of Styria turned ‘blue’ (the colour of the FPÖ). The FPÖ gained votes in all 285 municipalities, especially those with rural character. The ÖVP, by contrast, lost votes in all of them – except the one where State Governor Drexler resided (Der Standard, 2024d). The FPÖ also scored extraordinary wins in those municipalities in which, according to the plans of ÖVP and SPÖ, hospitals were to be closed.

A voter-flow analysis by the Foresight institute revealed that 23% of the FPÖ voters came from the ÖVP, another 24% were mobilized from previous non-voters. It may be assumed that some of these voters ‘returned’ to the FPÖ after the turmoil about the Ibiza scandal had subsided. The party performed below average with people under 34 and over 60 years of age, but above average with voters aged in-between, who felt probably most affected by the economic and social challenges. The higher the education level, the lower was the preference for the FPÖ. Immigration was the most important motive only for FPÖ voters, while the electorate in general regarded inflation and health as more important (Foresight, 2024).

In spite of the climate crisis, and the recent summer floods, the Greens plummeted from 12.1 to 6.2% of the votes. The Communists, getting only 4.5% (a loss of 1.5 points), were disappointed. The NEOS managed to slightly increase their share of the votes by 0.6 to 6%. Altogether, the smaller parties seemed to have suffered from the focus of public attention on the race for the top position.

Government formation

On the basis of the election results, none of the other parties seriously questioned the claim of the FPÖ and its party chairman Kunasek to the position of state governor. The only way to retain the governorship for the ÖVP would have been a three-party coalition between ÖVP, SPÖ and NEOS or, alternatively, Greens. Both options would have comprised a small majority in the state parliament (26 of 48 seats). However, many ÖVP as well as SPÖ mayors feared that such a coalition could lead to a new ‘blue’ (FPÖ) wave in the upcoming municipal elections, due in March 2025.

A two-party coalition between FPÖ and ÖVP or between FPÖ and SPÖ seemed to be a more logical consequence of the election results (after all, the FPÖ was the clear winner) and also to be more stable. Following a provision in the provincial constitution, Kunasek as leader of the strongest party invited the leaders of ÖVP and SPÖ to preliminary ‘sounding-out talks’. Both ÖVP and SPÖ signalled their eagerness to enter a coalition under the leadership of the FPÖ.

The FPÖ had to consider two strategies: On the one hand, a coalition with the SPÖ would have allowed it to tear down the ‘firewall’ (Brandmauer), which the Social Democrats had erected vis-à-vis the FPÖ because of its perceived anti-system or even anti-democratic rhetoric (a firewall which had not been respected by all SPÖ state party organisations, though). On the other hand, it could follow the examples of the states of Upper Austria, Lower Austria, Salzburg and Vorarlberg, where ÖVP-FPÖ coalitions had been built in recent years (with the FPÖ as junior partner only, though).

Finally, the FPÖ leadership opted for a coalition with the ÖVP and justified it by the larger policy overlaps. An additional motive was probably to confound the still ongoing coalition negotiations between ÖVP, SPÖ and NEOS at the federal level. Interestingly, an opinion survey by the Hajek institute showed that an FPÖ-ÖVP coalition in Styria was only preferred by 17% of the ÖVP voters, while 52% of them would have preferred a coalition with the SPÖ (Der Standard, 2024c). Former State Governor Drexler led the coalition negotiations for the ÖVP. After their completion, he was forced by his party to resign, however.

Mario Kunasek was elected state governor only with the votes of the FPÖ and ÖVP members of the state parliament. After Jörg Haider (1989-1991, 1999-2008) and Gerhard Dörfler (2008-2013) in Carinthia, he was the next politician of the FPÖ (or a party that split from it) to be elected state governor in Austria. The government programme of the new FPÖ-ÖVP coalition bore the trademark of the FPÖ. A primary goal was to make Styria less attractive for refugees and immigrants. For this purpose, a debit card was to replace cash transfers to asylum seekers, ‘religious clothes’ (obviously meaning headscarfs) were to be banned in the civil service, and a mission statement for integration was to be developed. In addition, social benefits were to be reserved only for persons ready to work hard. The project of the central hospital in Liezen was put on ice.

Conclusions

The state elections in Styria on 24 November 2024 resulted in a major change of government. For the first time in the history of the state, the right-wing populist FPÖ became the strongest party and formed a coalition government with the conservative ÖVP under the leadership of an FPÖ state governor. Growing dissatisfaction of many people with the state as well as with the national government, particularly their perceived incompetence to cope with multiple crises, prompted the change.

The ÖVP and the social democratic SPÖ tried to prevent this development by partly adopting FPÖ positions. The election results demonstrated, however, that this strategy can easily backfire as it can legitimize positions that formerly were regarded as taboo. Voters then may ‘not vote for the Schmiedl, but for the Schmied’ as a saying goes in Austria (which can roughly be translated as that they may ‘not vote for the copy, but for the original’). Future will tell whether the mainstream parties will be able come up with more effective strategies to counter the rise of the FPÖ, at the national as well as at the state level.

The data

References

Der Standard (2022, 3 June). Schichtwechsel in steirischer ÖVP: “Hermann im Glück” geht in Pension. Der Standard.

Der Standard (2024a, 29 January). FPÖ in Steiermark-Umfrage auf Platz eins. Der Standard.

Der Standard (2024b, 5 February). Nur jeder dritte Steirer sieht Land laut Umfrage auf richtigem Kurs. Der Standard.

Der Standard (2024c, 24 November). Steiermark-Wahl: Generation X und ältere Millennials haben eine Schwäche für die FPÖ. Der Standard.

Der Standard (2024d, 25 November). Städter haben die Grünen abgestraft und alle Gemeinden außer Passail die ÖVP. Der Standard.

Der Standard (2024e, 25 November). Wahlforscher: Bund und Van der Bellen waren “ganz sicher nicht” der einzige Grund für Drexlers Niederlage.

Fallend, F. (2015). ‘Der Proporz muss weg!’: Zu aktuellen Verfassungsreformdebatten in den österreichischen Bundesländern. In Europäisches Zentrum für Föderalismus-Forschung (EZFF) (ed.), Jahrbuch des Föderalismus 2015: Föderalismus, Subsidiarität und Regionen in Europa (pp. 278–292). Nomos.

Foresight (2024). Wahlanalysen. Landtagswahl Steiermark 2024.

Friedrich-Ebert-Stiftung (FES) (2017). Strategiedebatten Österreich – Nationalratswahl 2017.

Karner, C. (2021). “Ibizagate”: Capturing a Political Field in Flux. Austrian History Yearbook, 52, 253–269.

Kurier (2024, 22 October). Steirische Regierungsspitze hält Van der Bellens Entscheidung für “unverantwortlich”.

ORF (2024a, 19 November). Die Standpunkte der Landtagsparteien. ORF.

ORF (2024b, 23 November). Dreikampf um die Steiermark. ORF.

citer l'article

Franz Fallend, Regional election in Styria, 24 November 2024, Sep 2025,

à lire dans cette issue

voir toute la revue