Regional elections in Abruzzo and Basilicata, March-April 2024

Issue

Issue #5Auteurs

Davide Angelucci , Selena Grimaldi

Issue 5, January 2025

Elections in Europe: 2024

Context

The regional elections in Abruzzo, held on March 10, 2024, and those in Basilicata, on April 21 and 22 (along with the Sardinian elections in February), were the first contests of a fairly large series in numerical terms, followed by elections in Piedmont in June and those in Liguria, Umbria, and Emilia-Romagna in the fall, totaling seven Italian regions voting throughout the year (Grimaldi & Pala, 2024). In particular, the regional elections in Abruzzo and Basilicata were also the last to precede the European elections in June and therefore constituted, from the perspective of the national parties, a kind of barometer election (Anderson and Ward, 1996), useful for testing voting behavior and the potential performance of parties according to a vertical multilevel bottom-up logic (Schakel & Romanova, 2023). In other words, the outcomes recorded in a specific territorial arena (in this case, the regional level) can have similar repercussions in another arena (namely the European one), with spillover effects from the bottom (local context) to the top (European context).

On one hand, the two southern regions share the fact that throughout the so-called First Republic (1979–1990) they were strongholds of the Christian Democracy party, while since 1995 their histories have diverged significantly. In fact, whereas Abruzzo during the Second Republic (from 1995 onward) has been considered a competitive region (Passarelli & Tronconi, 2015) where there was alternation between center-right and center-left forces until 2014, Basilicata experienced a clear dominance of progressive forces up until 2019 (Mazzoleni, 2002).

On the other hand, more recently, the electoral competition shifted from a fragmented bicameralism (Chiaramonte, 2010) to a tripolar arrangement (Bolgherini & Grimaldi, 2017), which led in both regions first to the rise of center-left forces (in 2013 with Claudio Pittella in Basilicata and in 2014 with Luciano D’Alfonso in Abruzzo), but subsequently (in 2019) to the victory of the center-right with Marco Marsilio (Fratelli d’Italia, FdI) in Abruzzo and Vito Bardi (Forza Italia, FI) in Basilicata.

The 2024 elections recorded a strengthening of the center-right in both contexts, mainly due to a change in the structure of the competition which returned to a bipolar dynamic. This shift was caused by the significant decline of the Five Star Movement (M5S) and the inability of the so-called broad camp (that is, a coalition between the Democratic Party, other left-wing, centrist parties, and the M5S) to convince voters that it was a credible alternative to the right.

In the two regions, the main challengers in the 2024 elections were the center-right candidates, who were also the incumbent presidents: Marco Marsilio in Abruzzo and Vito Bardi in Basilicata. Both led coalitions composed of Fratelli d’Italia (FdI), Lega, Forza Italia (FI), and other centrist lists, opposing the center-left candidates. In the case of Abruzzo, the choice of the center-left presidential candidate was not too complicated and fell on Luciano D’Amico, a civic candidate but close to the center-left, leading a broad coalition composed not only of the Democratic Party (PD) and the Five Star Movement (M5S), but also centrist lists such as Azione and the Civic Reformists (which included Italia Viva), as well as the Greens and Italian Left (AVS), along with the list of the Abruzzo Insieme president (Angelucci, 2024a). In Basilicata, however, the identification of the progressive candidate was much more complex and traumatic: initially, the PD supported Angelo Chiorazzo, a businessman close to the Democrats, but this choice was unpopular with the M5S and led, after months of stalemate, to his withdrawal and the proposal by the national secretariats of the two parties of the civic candidate Domenico Larenza, an ophthalmologist with no previous political experience (Angelucci, 2024b). However, Larenza was eventually forced to withdraw because the regional bases of the PD and M5S, as well as the centrist lists, seemed very reluctant to support him. The final choice fell on Piero Marrese (PD), president of the province of Matera and mayor of the municipality of Montalbano Jonico (Angelucci, 2024b). This decision ended up weakening the allies of the so-called broad camp, since, unlike what happened in Abruzzo, the centrist forces of Azione and Italia Viva (IV) ran with the center-right.

The results

The fragmentation of presidential candidates was fairly limited in both regions, as there were only two candidates in Abruzzo, while in Basilicata there were three (in addition to Bardi and Marrese, also Eustacchio Follia for Volt). The competition dynamic returned to being bipolar, although party fragmentation remained moderately high since a total of 12 lists were presented in both regions.

Participation and votes

Voter turnout in both cases showed a decline: in Abruzzo, the average turnout in 2024 was 52.2%, just 0.9 percentage points lower than in 2019; while in Basilicata the drop was more marked, with a decrease of 4 percentage points compared to the previous election. However, it should be noted that less than half of the population turned out to vote in Basilicata, as participation stood at 49.8% (Angelucci, 2024b).

From an interpretative point of view, it is important to highlight three different aspects. On one hand, regional elections in Italy, as in the rest of Europe, often function as “second-order elections” (Reif & Schmitt, 1980), meaning elections where the stakes are considered less significant than in general political elections. For this reason, turnout tends to be lower and ruling parties are usually penalized. On the other hand, in Italy electoral participation has historically varied greatly by geography, with lower turnout in southern areas compared to the central-northern regions, regardless of the type of election (Mannheimer & Sani, 2001). Finally, the importance given to these elections by national party leaders—who came to the regions to support their respective candidates, considering them a test of the possible outcome of the European elections—probably mitigated the decline in turnout (Scantamburlo et al., 2024), which might otherwise have been greater, given the growing disconnect between citizens and politics.

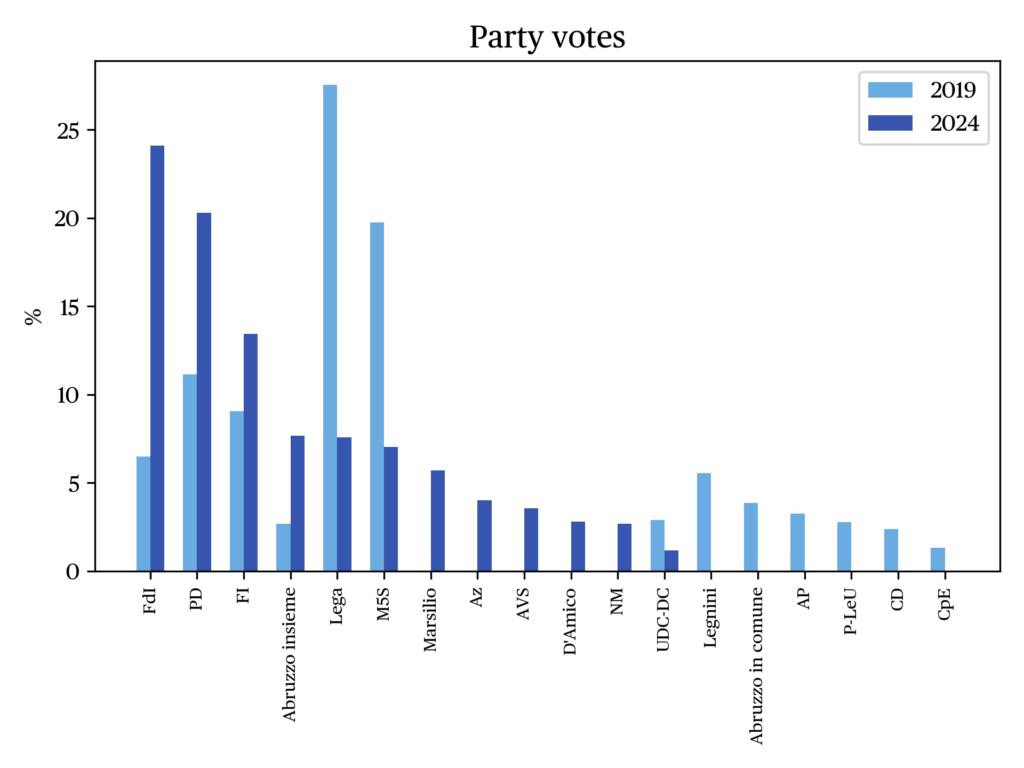

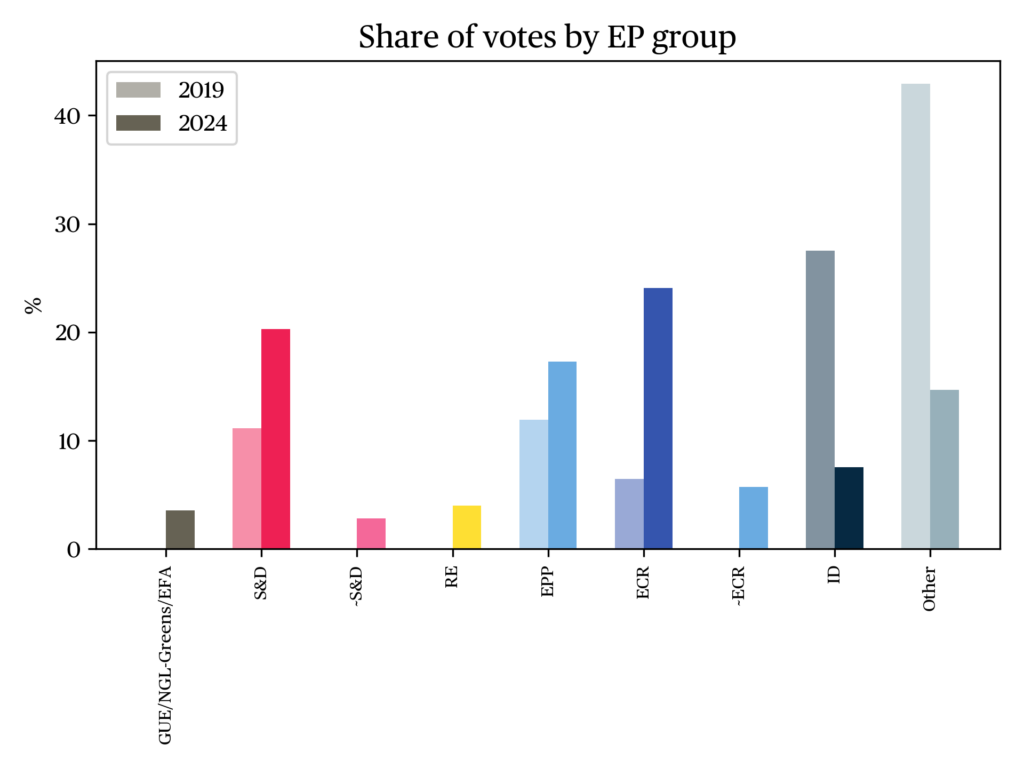

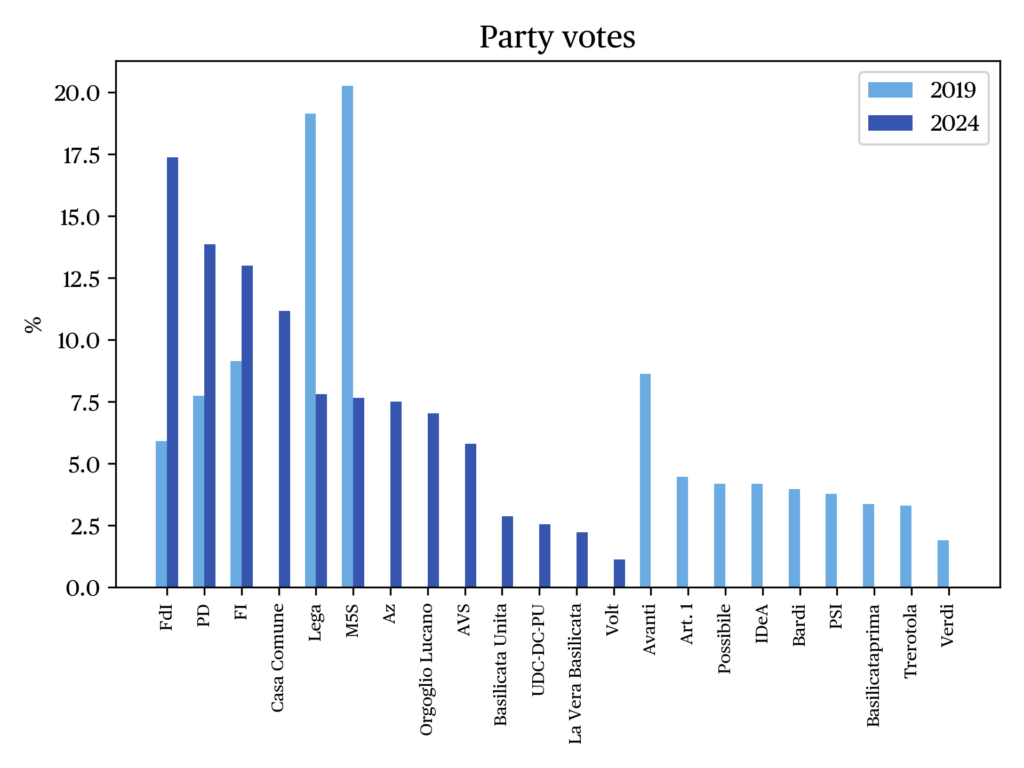

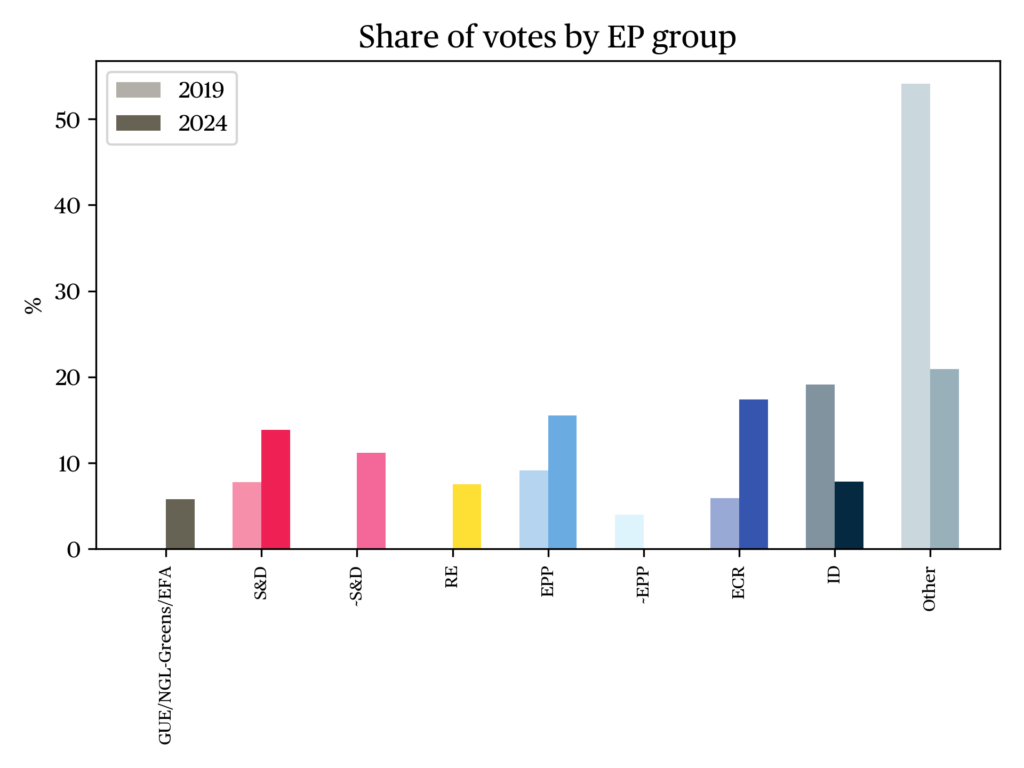

Turning to the results of the main parties (see “the data”), four key aspects are common to both regions:

- The most voted party was the main governing party, Fratelli d’Italia (FdI), which obtained 24.2% of the votes in Abruzzo and 17.4% in Basilicata, registering an impressive increase compared to 2019, respectively by 17.5 and 11.5 percentage points;

- The main opposition party, the Democratic Party (PD), did not really lose in these elections, as it was the second party in both regions and also recorded a notable increase in votes compared to 2019, reaching 20.3% in Abruzzo and 13.9% in Basilicata;

- Forza Italia (FI) also showed a positive performance and growth compared to the previous election, becoming the third party with about 13% of the votes in both regions;

- The real losers in these elections were, in both cases, the Lega within the center-right coalition and the Five Star Movement (M5S) within the center-left coalition. In Abruzzo, the Lega lost nearly 20 percentage points, and in Basilicata more than 11 points compared to 2019, settling just above 7.5% of the votes in both regions.

Moreover, at the regional level, the configuration of the center-right coalition changed, with FdI replacing the Lega as the largest party, similarly to what happened in the previous 2022 national elections.

Finally, the M5S was chosen by only 7% of voters in Abruzzo and 7.8% in Basilicata, with a loss of over 12 percentage points compared to 2019 in both cases. This debacle is attributable to the complete change in M5S’s political strategy, which involved joining a specific coalition—the center-left—rather than running autonomously without any alliance. This choice was unpopular with the Five Star Movement’s electoral base.

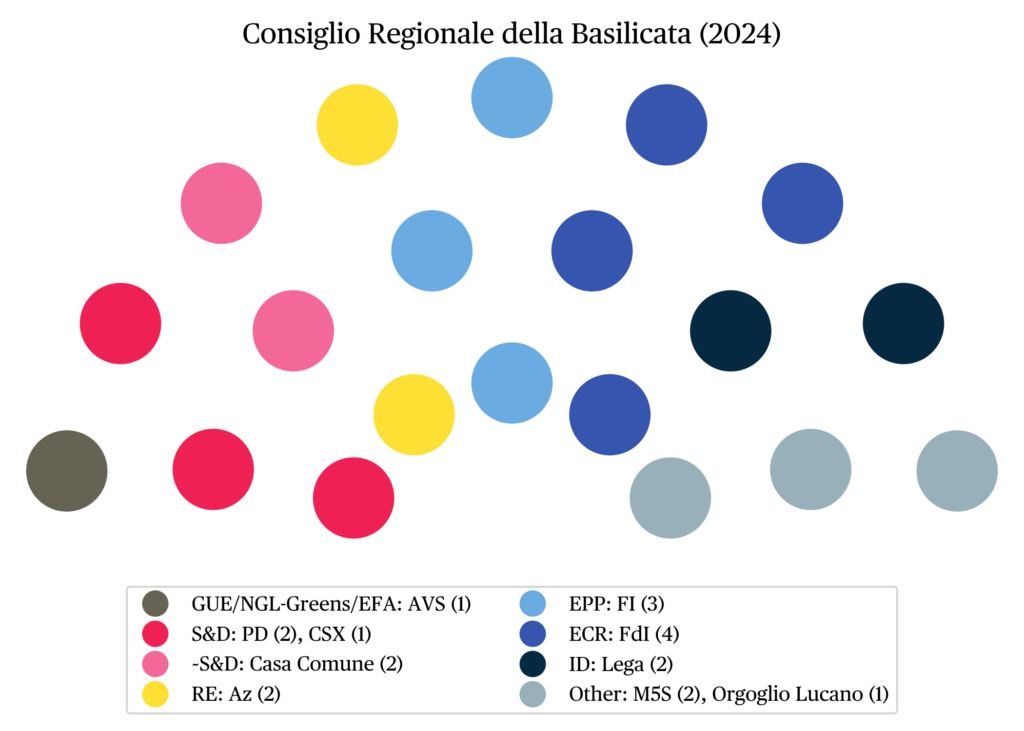

The defeat of the center-left, therefore, does not seem attributable to the Democratic Party (PD) but rather to the very poor performance of the Five Star Movement (M5S) in both regions. Similarly, the loss of the progressive camp cannot be blamed on the choice of candidates, since in both Abruzzo and Basilicata the center-left presidential candidates received more votes than the lists connected to them: D’Amico obtained 284,748 votes while his lists received 262,565; Marrese received 113,979 votes compared to 108,135 votes for the lists linked to him. However, while in Abruzzo the gap between Marsilio (53.5%) and D’Amico (46.5%) was 7 points, in Basilicata Bardi (56.6%) outpaced Marrese (42.2%) by more than 11 points. This more marked gap can be attributed both to a generally positive assessment by the electorate of Bardi’s governing abilities and to the success of the centrist lists Azione and Italia Viva (the latter running with the Orgoglio Lucano list) in Basilicata, both of which obtained more than 7% of the votes and a total of 3 seats (2 and 1 respectively), ultimately playing a decisive role in Bardi’s victory (Angelucci, 2024b).

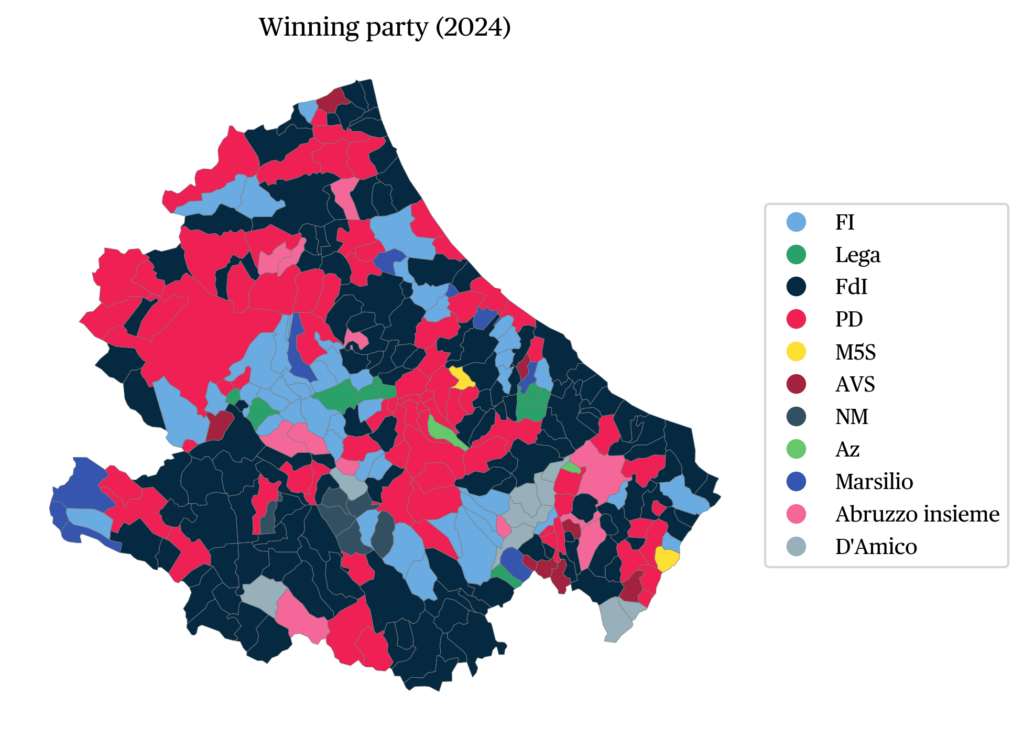

The geography of the vote

In line with an established trend in the Italian political landscape (Cataldi et al., 2024), the regional elections in Abruzzo and Basilicata confirmed the center-right’s ability to achieve its best results in small towns, rural areas, and the country’s most peripheral regions. The center-left, on the other hand, was relatively more competitive (though not necessarily victorious) in urban centers.

In Abruzzo, a clear territorial division between the coast and the inland areas has emerged (see Figure a). In the coastal provinces of Chieti, Pescara, and Teramo, the average margin between the center-right presidential candidate and the center-left candidate was about 2 percentage points. Marsilio (center-right) won in Chieti (+3.1) and Pescara (+3.4), while he narrowly lost in Teramo (-0.4). However, the decisive result came from the province of L’Aquila: the only province not facing the sea, the largest in terms of territory, with the highest number of municipalities, but also the least densely populated. Here, the center-right dominated with a margin of nearly 23 percentage points, creating a clear advantage in the overall tally. This initial data clearly shows a region split in two by a distinct fracture dividing the coast from the inland. Another fracture separates the larger urban centers from the smaller, relatively more peripheral municipalities (mostly located along the Apennine ridge). Among the 17 larger municipalities (over 15,000 inhabitants), the center-left won in 7 cities, including Pescara, Teramo, and Vasto, while the center-right prevailed in the remaining 10. Overall, the center-right obtained 51.4% of the vote in the larger municipalities, against 48.6% for the center-left. In the smaller municipalities, the gap widened (center-right 55.5% – center-left 44.5%). The center-right won 156,192 votes in the larger centers (+8,708 votes compared to the center-left) and 171,468 votes in the smaller municipalities, with a net margin of 34,204 votes. The center-left’s defeat in Abruzzo was therefore largely concentrated in the province of L’Aquila, particularly in its smaller municipalities (as many as 105). This result confirms the structural divide between urban and peripheral areas already observed at the national level (Cataldi et al., 2024): the center-left is relatively competitive in the larger and more integrated urban centers, while the center-right dominates the internal and rural areas. Although the province of L’Aquila does not show abnormal macroeconomic indicators compared to the other Abruzzo provinces, it suffers from acute problems of depopulation, aging, and infrastructural difficulties, which render it marginal socially and territorially (Angelucci, 2024). In these areas, where access to services is limited and the demand for social protection is stronger, it is the center-right that has consolidated its roots. It is therefore unsurprising that the debate on infrastructure—such as the modernization project of the railway line connecting Rome to Pescara, passing through the province of L’Aquila—has been central. For example, just days before the Abruzzo vote, the government approved a funding allocation of over 700 million euros under the Development and Cohesion Fund 2021-2027 for the modernization work on the Rome-Pescara line. This came after the modernization and upgrade project had initially been fully included among those financed by the National Recovery and Resilience Plan (PNRR), only to be later removed in 2023 by the Meloni government to redirect funds toward projects considered more urgent or easier to implement to meet PNRR goals. Whether this government decision influenced the voting choices of Abruzzo’s electorate is difficult to assess. What clearly emerges, however, is the stark divide separating voters living in more marginal and disadvantaged areas from the parties of the progressive camp. It is precisely in these areas—where the need for social and economic protection is plausibly stronger—that the center-right has planted its deepest and strongest roots.

| Marsilio | D’Amico | Difference CDX-CSX | |

| Chieti | 51.5 | 48.5 | 3.1 |

| L’Aquila | 61.3 | 38.7 | 22.6 |

| Pescara | 51.7 | 48.3 | 3.4 |

| Teramo | 49.8 | 50.2 | -0.4 |

| Larger towns | 51.4 | 48.6 | 2.9 |

| Smaller towns | 55.5 | 44.5 | 11.1 |

| Regional total | 53.5 | 46.5 | 7.0 |

Note: The upper part of the table shows the percentage of valid votes obtained by the presidential candidates in the Abruzzo provinces. The lower part of the table shows the percentage of valid votes obtained by the presidential candidates in the larger municipalities (over 15,000 inhabitants) and the smaller municipalities. Source: Adapted from Angelucci (2024a).

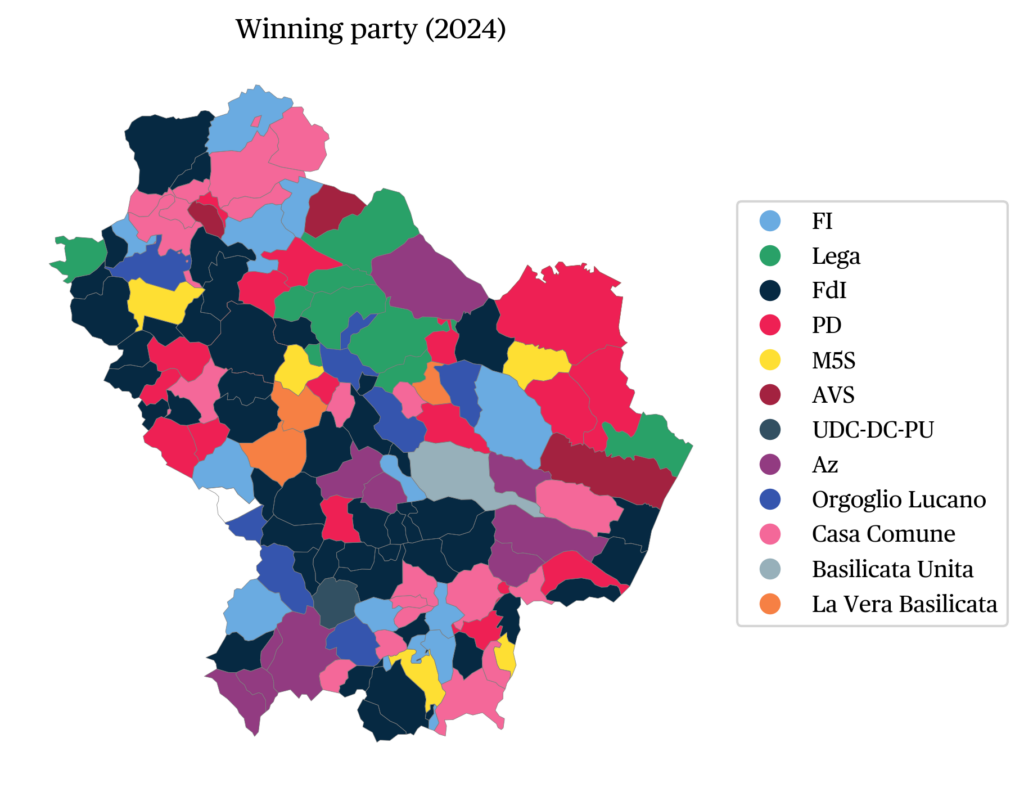

Similarly, the elections in Basilicata were characterized by a heterogeneous territorial distribution of the vote (see Figure b). Bardi won with a margin of over 14 percentage points over Marrese, but the gap varies at the municipal level. In the five larger municipalities (over 15,000 inhabitants), Bardi prevailed in Potenza, Policoro, and Melfi, while Marrese won in Matera and Pisticci. In the larger centers (above 15,000 inhabitants), the center-right obtained 51.2% compared to 46.4% for the center-left, with a gap of 4.8 points. In the smaller municipalities (under 15,000 inhabitants), Bardi’s advantage significantly widened: 59.1% against 40.2%, with a difference of nearly 19 percentage points.

| Bardi | Marrese | Follia | Difference CDX-CSX | |

| Matera | 48.1 | 49.9 | 2.0 | -1.9 |

| Potenza | 60.9 | 38.3 | 0.8 | 22.6 |

| Total votes in larger towns | 51.2 | 46.4 | 2.4 | 4.8 |

| Total votes in smaller towns | 59.1 | 40.2 | 0.6 | 18.9 |

| Total votes at the regional level | 56.6 | 42.2 | 1.2 | 14.5 |

Note: The upper part of the table shows the percentage of valid votes obtained by the presidential candidates in the provinces of Matera and Potenza. The lower part of the table shows the percentage of valid votes obtained by the presidential candidates in the larger municipalities (over 15,000 inhabitants) and the smaller municipalities. Source: Adapted from Angelucci (2024b).

Conclusions

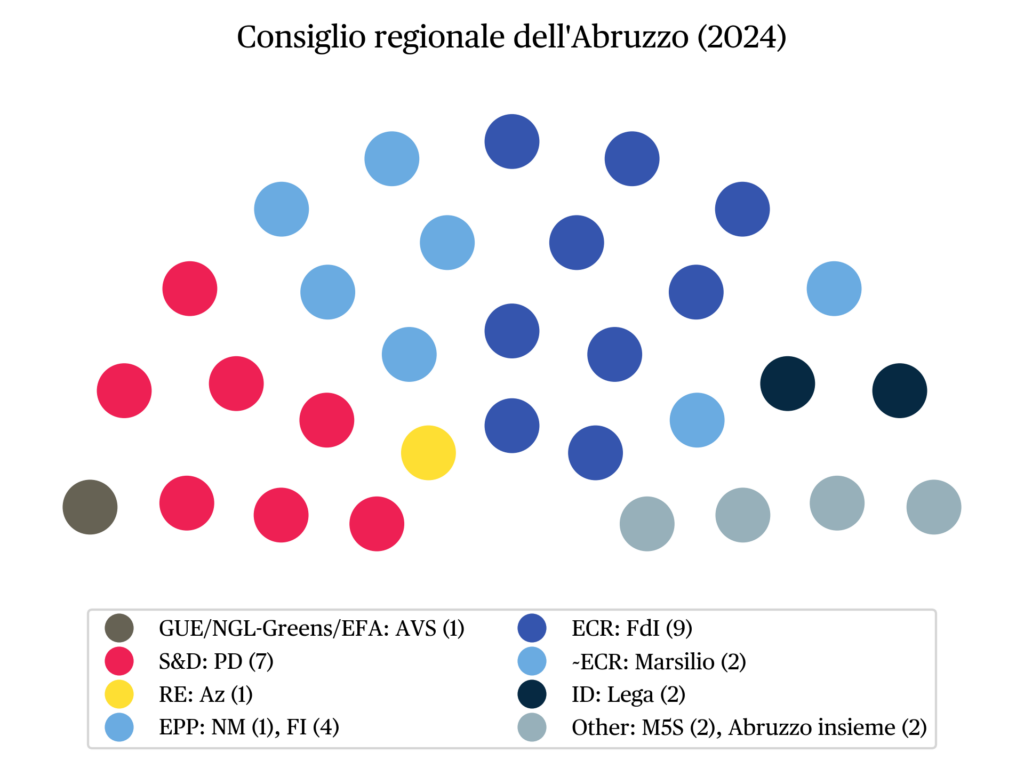

The elections in Abruzzo and Basilicata do not seem to confirm the Second Order Election (SOE) model (Reif & Schmitt, 1980). Indeed, despite the decline in turnout compared to the 2022 national elections, the parties in national government were not punished in these regional elections; on the contrary, both center-right presidents were re-elected. From this perspective, the hypothesis put forward by Scantamburlo et al. (2024) appears more plausible: being the main party in regional government can be an important resource to mitigate the negative trends predicted by the SOE model for parties in government at the national level. In other words, both in the case of Marsilio and Bardi, there was a kind of incumbency bonus that substantially increased the likelihood of their parties holding on, which indeed recorded some of the best performances in Italy in these regions (respectively, FdI in Abruzzo with 24.2% of the vote and FI in Basilicata with 13%).

Furthermore, the analyzed data confirm the dichotomy between urban and rural areas, a pattern previously observed in Italy and explored by other studies (Cataldi et al., 2024). In other words, both in Abruzzo and Basilicata—albeit with some nuances—there is a substantial dominance of the progressive coalition in urban areas, while in rural areas the center-right coalition tends to prevail.

Broadening the perspective to the regional elections held across Europe in 2024 (Grimaldi & Pala, 2024), the elections in Abruzzo and Basilicata show some similarities as well as differences. The main similarities concern the substantial stability of the governing coalitions; indeed, as in most European cases, there was no change in power, with incumbent presidents being re-elected (see, for example, the cases of regional presidents in the Azores, the German-speaking Community of Belgium, Brandenburg, Saxony, Galicia, South Moravia, Central and Southern Bohemia, and Piedmont). Another similarity is the notable success of center-right parties, which have often succeeded in winning governments in various European regions; in fact, the cases where center-left coalitions prevailed in 2024 were quite few (e.g., Catalonia, Basque Country, Brandenburg, Sardinia, Umbria, and Emilia-Romagna). Finally, these two Italian regions align with the general trend that saw the success of European populist parties in this round of regional elections (notably Chega in Portugal, Vox in Spain, ANO in the Czech Republic, PiS in Poland, th eAfD in Germany, and the FPÖ in Austria). However, in Italy, only the far-right populist party FdI gained significant support, while the Lega experienced a substantial decline. The main discontinuity in these elections concerns voter turnout: the Italian regional elections, including those in Abruzzo and Basilicata, had considerably lower participation than the European average, which hovered around 61%, likely because some of the regions with the strongest territorial identities were voting. Additionally, Basilicata recorded a turnout rate even lower than the Italian average (50.6%), though it was not the lowest overall—that distinction belongs to Liguria, with 46%.

The data

Abruzzo

Basilicata

References

Anderson, C. J., & Ward D. S. (1996). Barometer Elections in Comparative Perspective. Electoral Studies, 15(4), 447–460.

Angelucci, D. (2024a). Le Elezioni Regionali del 2024 in Abruzzo. Regional Studies and Local Development, 5(2), 1–19.

Angelucci, D. (2024b). Le Elezioni Regionali del 2024 in Basilicata. Regional Studies and Local Development, 5(2), 1–15.

Bolgherini, S., & Grimaldi, S. (2017). Critical election and a new party system. Italy after the 2015 regional election. Regional & Federal Studies, 27(4), 483–505.

Cataldi, M., Emanuele, V., & Maggini, N. (2024). Territorio e voto in Italia alle elezioni politiche del 2022. In A. Chiaramonte & L. De Sio (Eds.), Un polo solo. Le elezioni politiche del 2022 (pp. 177–216). Il Mulino.

Chiaramonte, A. (2010). Dal bipolarismo frammentato al bipolarismo limitato? Evoluzione del sistema partitico italiano. In R. D’Alimonte & A. Chiaramonte (Eds.), Proporzionale se vi pare (pp. 203–228). Il Mulino.

Grimaldi, S., & Pala, C. (2024). Le elezioni regionali del 2024 in Europa: i limiti del modello di secondo ordine e la vittoria delle forze di (centro)destra. Regional Studies and Local Development, 5(2), 1–8.

Mannheimer, R., & Sani, G. (2001). La conquista degli astenuti. Il Mulino.

Mazzoleni, M. (2002). I Sistemi Partitici Regionali in Italia. Dalla Prima alla Seconda Repubblica. Rivista Italiana di Scienza Politica, 32(3), 459–491.

Passarelli, G., & Tronconi, F. (2015). I nuovi sistemi partitici nelle regioni italiane. In S. Bolgherini & S. Grimaldi (Eds.), Tripolarismo e destrutturazione. Le elezioni regionali del 2015 (pp. 55–769. Istituto Cattaneo.

Reif, K., & Schmitt, H. (1980). Nine Second-order National Elections: A Conceptual Framework for the Analysis of European Election Results. European Journal of Political Research, 8, 3–44.

Scantamburlo, M., Vampa, D., & Turner, E. (2024). The costs and benefits of governing in a multi-level system. Political Research Exchange, 6(1), 1–22.

Schakel, A. H., & Romanova, V. (2023). Moving beyond the second-order election model? Three generations of regional election research. Regional & Federal Studies, 33(4), 399–420.

citer l'article

Davide Angelucci, Selena Grimaldi, Regional elections in Abruzzo and Basilicata, March-April 2024, Sep 2025,

à lire dans cette issue

voir toute la revue