Regional election in Provence-Alpes-Côte d'Azur, 20-27 June 2021

Issue

Issue #2Auteurs

Christine Pina , Gilles Ivaldi

21x29,7cm - 167 pages Issue 2, March 2021 24,00€

Elections in Europe : June 2021 – November 2021

Far from resulting in an upheaval of the political equilibrium, the 2021 regional election in the Provence-Alpes-Côte d’Azur (PACA, Région Sud/South) has nevertheless nuanced and reflected the progression of some trends observable since the 1990s-2000s.

A Much-followed Regional Election

In the PACA region, the regional election could have gone unnoticed as at first glance it seemed to be over before it even took place. A few weeks before the June 2021 deadline, a likely RN-LR duel in the second round was taking shape, a self-fulfillement of pre-electoral polls. The eight polls published in June before the first round were giving the Thierry Mariani list (RN, ex-UMP) an average of 42% of the vote, against 33% for the list of the outgoing president, Renaud Muselier, and barely 15.5% for the left-wing unity list led by the environmentalist Jean-Laurent Félizia (EELV).

This specific framing echoed by the media before the election may give us an impression of a déjà vu as far the national French political discourse goes. In addition to the fact that it gives pride of place to comments on a PACA region as an easy prey for the National Front/National Rally, it also reflects the early strong position of the far right in the South-East since the 1990s, whether in municipal, departmental or regional bodies, even though the legislative election of 2017 found a noticeable decline of the Lepenist movement in the South.

However, there are some important differences as far as 2021 election is concerned: first of all, the outgoing president, Renaud Muselier, has been leading the region since the elected president Christian Estrosi had quit in 2017. It is therefore the first time that Muselier is heading an electoral list. Secondly, the PACA election is an opportunity for revenge for the left, deprived of regional representation since its defeat and withdrawal before the 2nd round in 2015; it would not want to withdraw in case of a second round in favour of the extreme right again. The calls for unity and mobilization of voters reflect the double challenge of these regional elections: to avoid a victory for the RN and to weigh again in the assemblies. Even though in Marseille, for example, the municipal election has reignited hope in activists and elected officials on the left. Finally, and perhaps the most significantly, while in 2015 the polls gave the advantage to the classical centre-right, in 2021 it is the Thierry Mariani list (RN, ex-UMP) who in early May 2021 appeared as the likely winner of the election.

Far from the announced repetition of 2015, the election of 2021 has highlighted noteworthy changes. First of all, the regional election did not take place in partisan silence. By announcing on 2 May in Le Journal du dimanche the withdrawal of the LREM list in favour of the Muselier list Jean Castex, then Prime Minister, showed how essential the PACA election was for the Macron’s movement in the perspective of the upcoming presidential election, and perhaps revealing the right-wing positioning of LREM. Christian Estrosi, the mayor of Nice, and Hubert Falco, the mayor of Toulon, who were in favour of this “political realignment” (in the words of the Prime Minister) took the opportunity to leave the Republicans, denouncing the Parisian apparatus of the LR and the deafness of the party as it faced the open risk of a far-right victory.

For their part, Les Republicains were split into two camps: those in favour of negotiations on a case-by-case basis with the presidential party, and those elected representatives and activists who considered any alliance with LREM as a ruse or even a betrayal. The latter ones were represented by Éric Ciotti (MP for the Alpes-Maritimes) and Bruno Retailleau.

Another major change had been the recomposition of the left in the region. In 2015 Christophe Castaner (PS) led the regional list of the left while EELV stood alone, led by Sophie Camard. In 2021 it is the ecologist Jean-Laurent Félizia (EELV) who leads this entire political family by managing to rally the PS, the PC and Génération.s on the same list. Beyond the ecologist offensive at the ballot box since the 2010s, this development illustrates the fragility of a partisan left (PS and PC) pushed around in local elections by EELV, who were in search of a leader after the defections to LREM in 2017 and forced to accomodate the supporting forces in order not to disappear from the assemblies.

In the end, 9 lists would go on to compete in the PACA region in the first round. In addition to the three covered above, we must mention, inter alia, the list led by Jean-Marc Governatori (Cap Écologie), newly elected to the municipal council of Nice, and the list led by Isabelle Bonnet for Lutte Ouvrière.

A Falling Turnout, and the RN and the Left at the Bottom

The participation rates, as in many French regions, fell very sharply compared to 2015: in the region as a whole the abstention rate increased by 18.2 points and reached 66.3%. If in 2015, the people who did not vote formed the majority only in Bouches-du-Rhône, in 2021 it is the case in all departments.

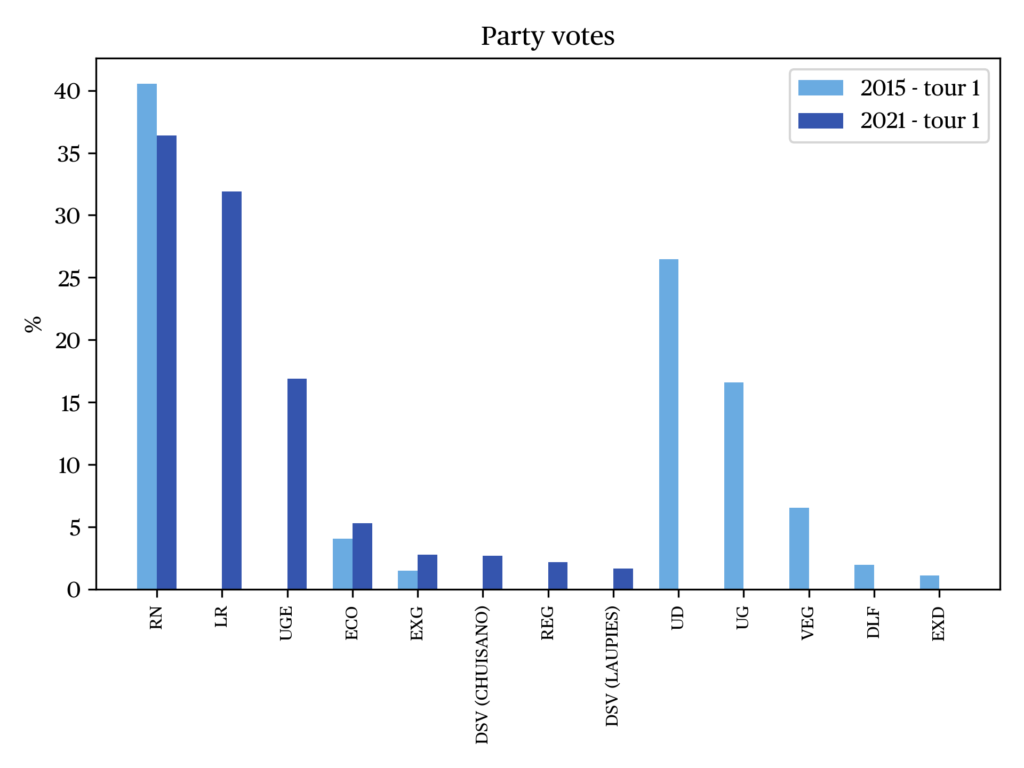

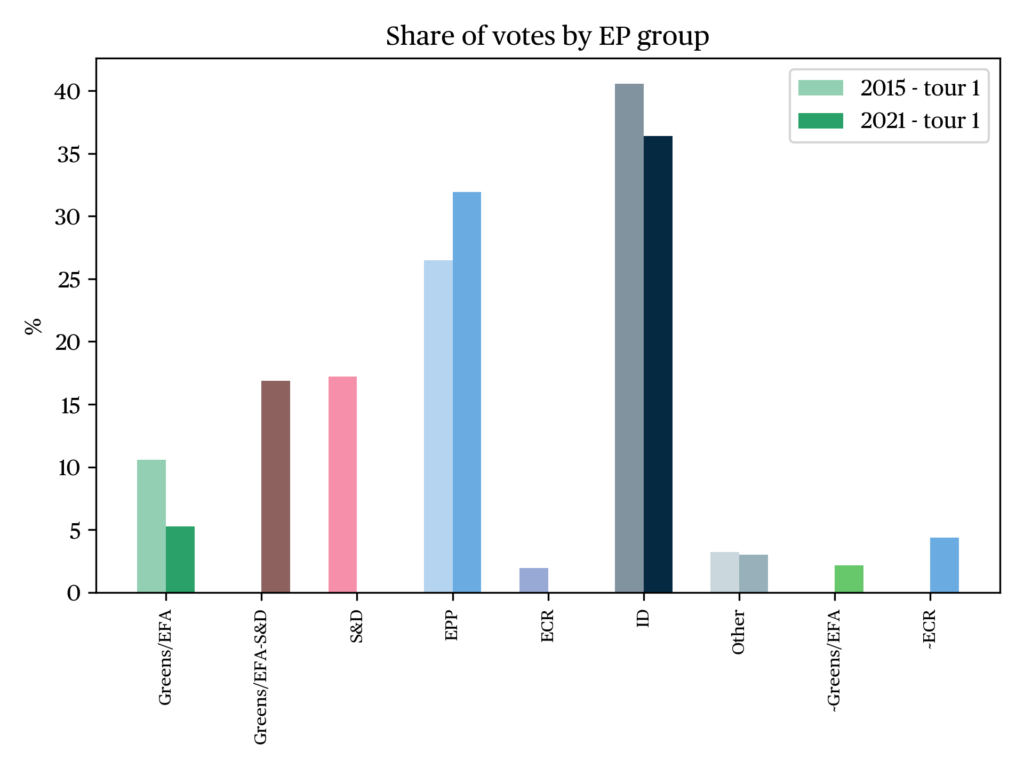

Abstention seems to have affected the different political camps in an unequal way. In terms of percentages of registered voters, the two forces that declined the most were the National Rally and the left-wing list. The National Rally generally seems to have mobilised its voter base less than the moderate right: Renaud Muselier lost only three points compared to Christian Estrosi’s score in 2015; for the National Rally, it was almost nine points, and for the left more than six.

In the second round, the abstentionist trend was confirmed, even if the participation mildly raised. Abstentionism is anything but new: apart from the fact that it follows on from the records already observed during the 2020 municipal elections, it testifies to the low level of enthusiasm among voters. In a context still marked by the uncertainties of the pandemic the voters, in PACA as elsewhere, turned to the parties in place at the regional level.

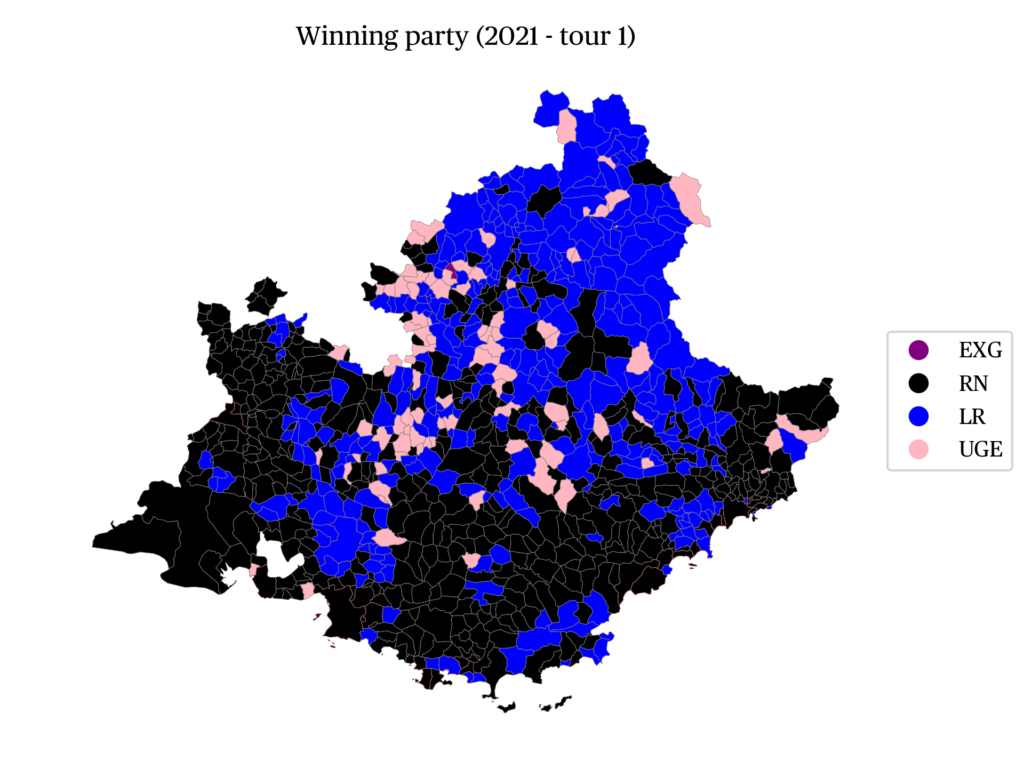

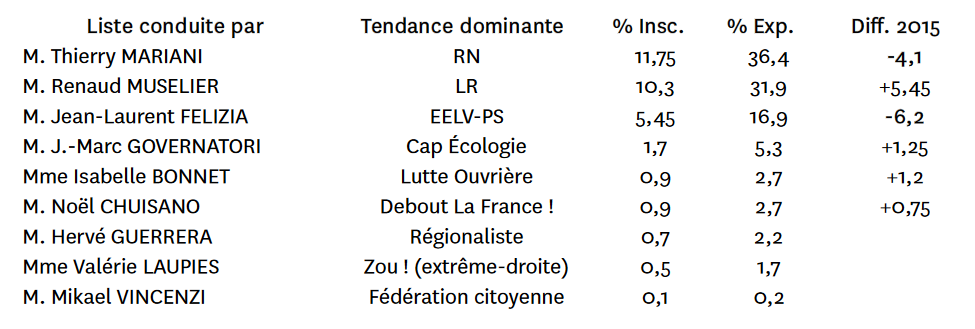

On the evening of the first round, three lists could claim to be in the running: Thierry Mariani’s list, which came out on top with 36.4% of the vote, Renaud Muselier’s list, which was close behind with 32%, and the left-wing union list (see Figure a). The results underline the extreme weakness of the latter: with 17% of the vote, the left has fallen significantly compared to 2015

1

(24%) against the right-RN duopoly. The list led by Jean-Laurent Félizia had to choose, just like in 2015, between two options: to withdraw in order not to jeopardise a victory for the centre-right, or stay in the game and hope to be in the council again. Finally, after 24 hours of negotiations and consultations, the leader of the “Social and Environmental Rally” announced the withdrawal of his list, leaving the centre-right and the far-right to face each other alone in the second round.

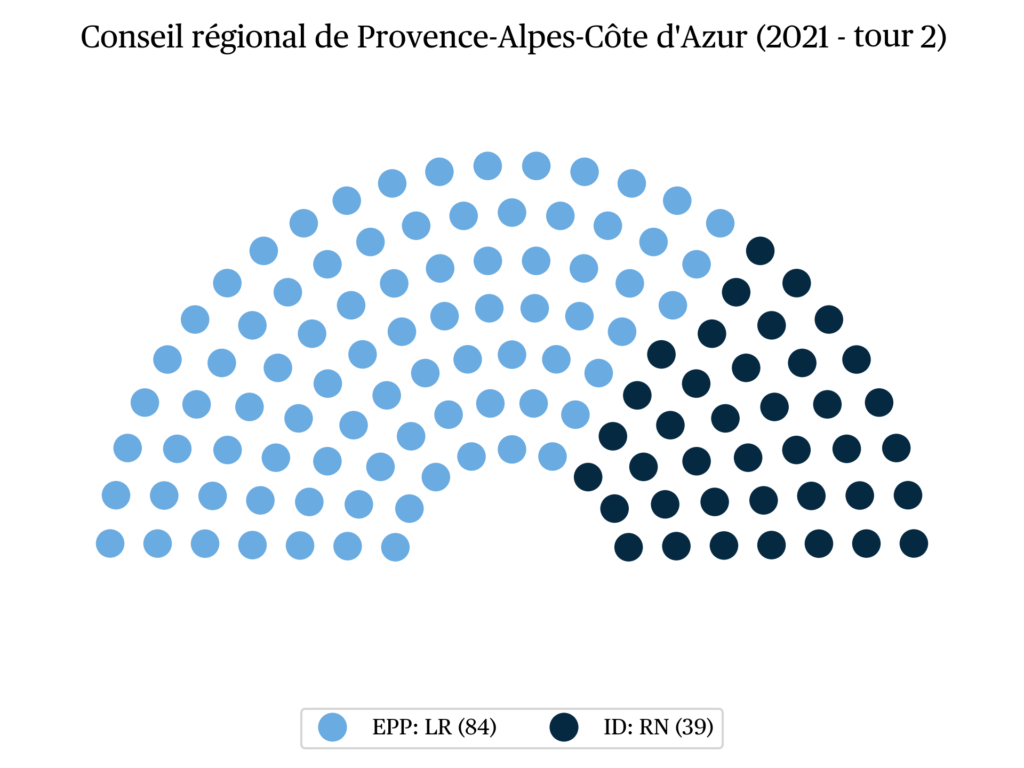

For the Renaud Muselier’s list to finally have won on the 27th of June with 57.3% of the votes, the explanation cannot be only the renunciation of the left. It is due to the reversal of positions within the Republicans (Éric Ciotti ended up supporting the Muselier list), but also to the declining results of the National Rally in the region. Whether the first or the second round is concerned, the party is losing votes (except in the Alpes-Maritimes where it gained ground), especially in the Bouches-du-Rhône but also in the Vaucluse where Marion Maréchal-Le Pen’s list had a majority in the second round of the 2015 regional elections.

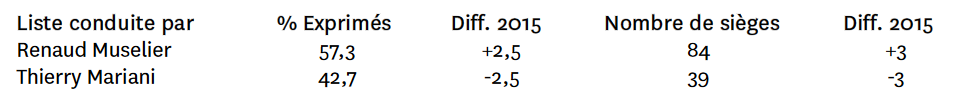

In 2021, if Thierry Mariani’s list came out on top in 4 of the 6 departments of the region in the evening of the 1st round (except for Alpes-de-Haute-Provence and Hautes-Alpes) (see Figure c), the 2nd round sealed the effects of a republican front built as an emergency response but not without contrition (Figure b). In the end, the results attest to the relative failure of the NR’s strategy of “de-demonisation” through the choice of entrusting the head of the list to the ex-UMP Thierry Mariani, who has since failed to win the region.

With 84 seats, Renaud Muselier’s list solidified its domination of the Regional Council and had to deal once again with an opposition made up solely of NR members.

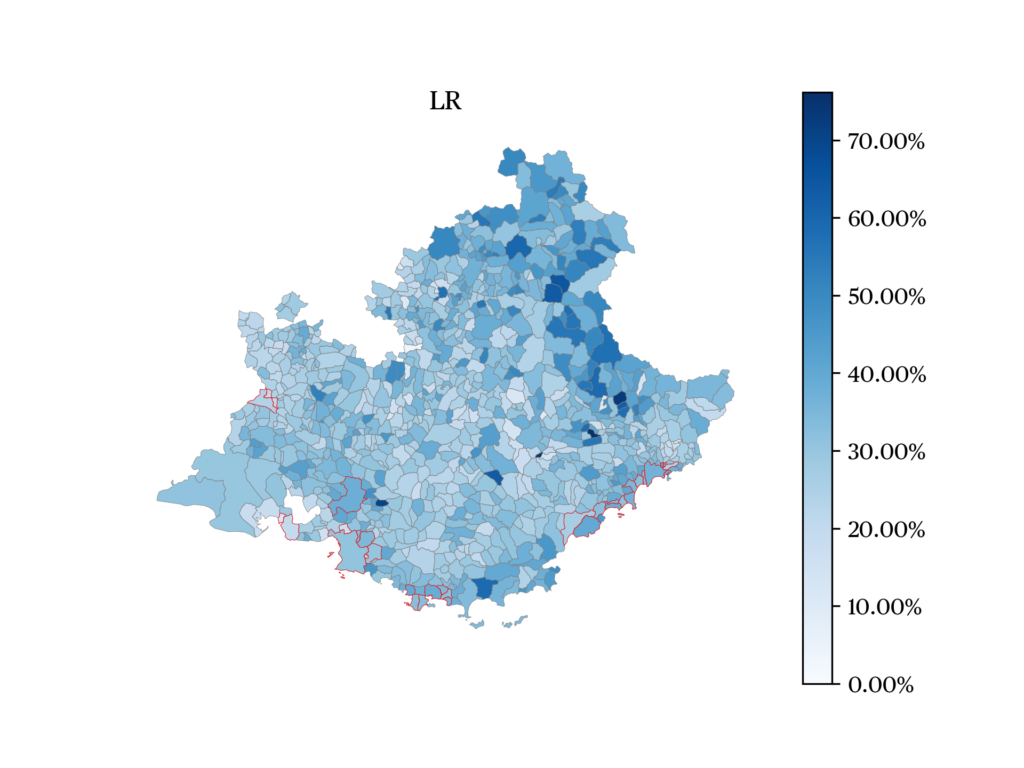

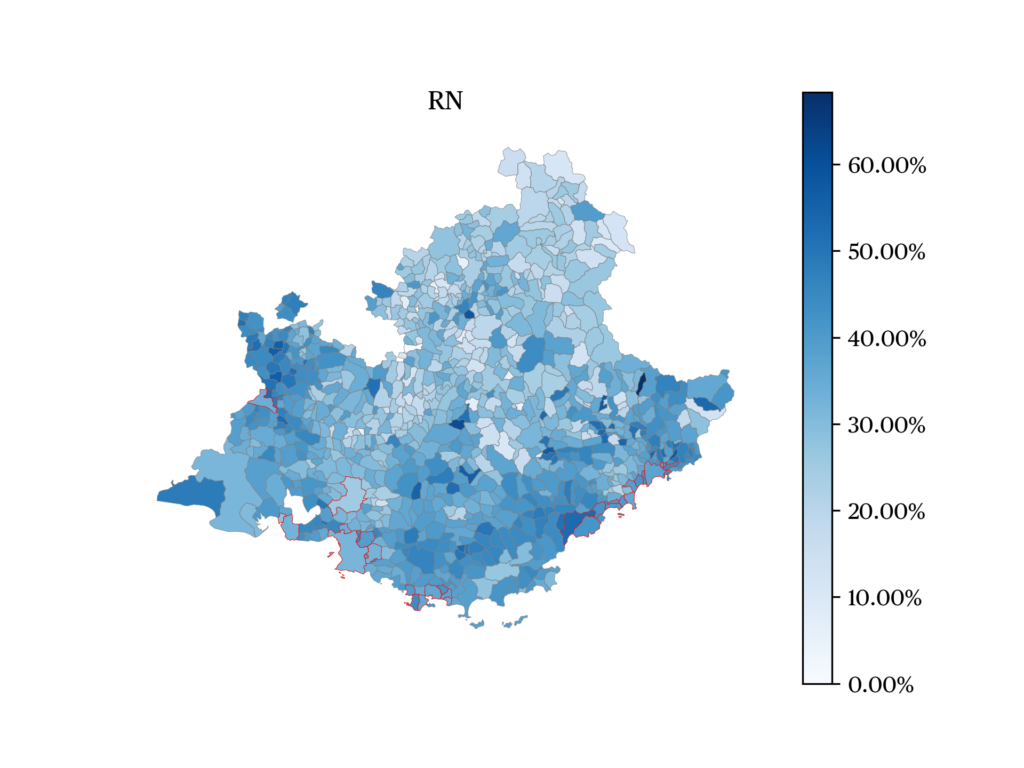

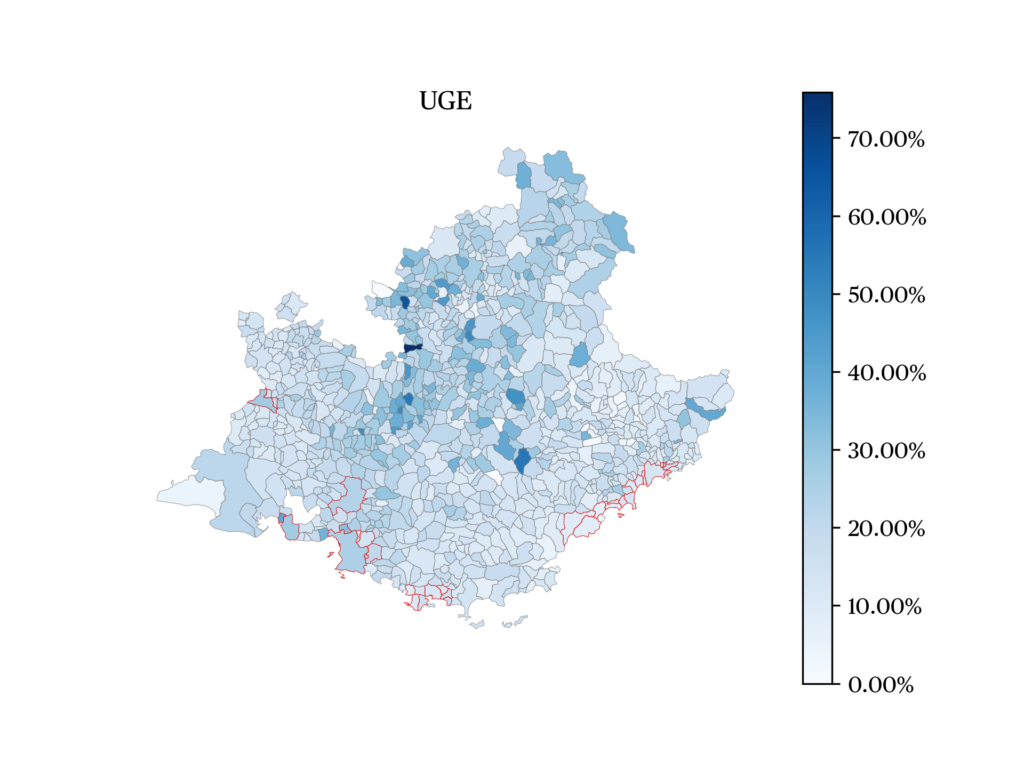

Spatial Dynamics: a Plural Region

In the departments that make up the region, we observe quite different dynamics linked to specific political identities (see Figure c and d). The Félizia list obtained its best scores in the two Alpine departments, the Hautes-Alpes and the Alpes-de-Haute-Provence, which have long been marked by the influence of the left and trade unionism, as well as in the Bouches-du-Rhône, which is traditionally more left-wing.

The Mariani list came out on top in four of the six departments – with the exception of the Alpes-de-Haute-Provence and the Hautes-Alpes — whereas it achieved its best scores in Var and Vaucluse, two traditional bastions of the far-right in the region.

In the Alpes-Maritimes, the results of the first round confirm the rebalancing to the right that has taken place in the department in favour of Marine Le Pen’s party since the previous regional elections of 2015. Contrary to the other coastal departments, the results of the Muselier list in 2021 are weaker than those of the Estrosi list six years earlier, in a context marked by deep tensions within LR between supporters of an alliance with LREM, such as Christian Estrosi (Nice’s mayor), and those such as Eric Ciotti who are fiercely opposed to it.

In the second round, the Muselier list came out on top in all the departments of the region, benefiting everywhere, at least in part, from the Republican front supported in particular by Félizia and Governatori.

The incumbent president of the regional council achieved his best results notably in the three departments where the left obtained its best results in the first round, namely the two Alpine departments and the Bouches-du-Rhône. It is also there that he recorded his strongest progress between the two rounds, testifying to a stronger mobilisation of the moderate electorate in these two areas. The NR list achieved its best performances in its traditional strongholds of the Var and the Vaucluse, as well as in the Alpes-Maritimes.

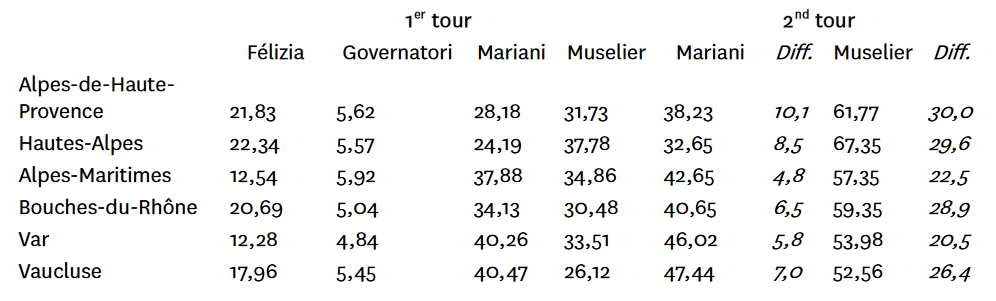

The analysis at the level of the municipality of the correlations between the gains of R. Muselier between the two rounds and the level of the different lists in the first round confirms that the progression of the classic right was stronger on average where the scores in favour of the left and the Governatori list were higher.

2

On the other hand, there was no significant correlation between the level of the two finalists, abstention or the increase in participation in the second round.

On the left, the strongest correlations are visible in the Hautes-Alpes, Alpes-Maritimes, Vaucluse and Bouches-du-Rhône: the gains of the list led by the outgoing president of the Regional Council are all the higher as the left was strong in the municipality in the first round (see Figure e). In the Var or the Alpes-de-Haute-Provence, on the other hand, the correlations appear much weaker and the transfers from the left to the Muselier list seem to have been less systematic.

Socio-Demographic Determinants: Unemployment and the Vote of Working-Class Communes

Behind the performances of the main lists we can also see the main socio-demographic cleavages that generally structure the vote in PACA. First of all, the importance of the NR vote in the region’s major cities: in the first round, the Mariani list gathered 37.1% of the votes cast in Nice, 36.5% in Toulon, 31.9% in Marseille and 34% in Avignon. This more urban presence of the far-right in PACA contrasts with its weakness in most large French cities: in the first round, Marine Le Pen’s party barely received 7.9% of the votes in Paris, 10.1% in Lyon and 11.2% in Toulouse, for example.

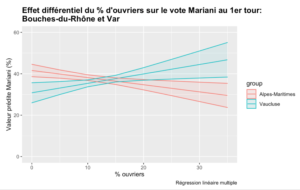

The popular dimension of the vote in favour of the NR can also be found in PACA, but with different effects depending on the context. As illustrated in Figure f, the working class presence has a positive and significant effect on the Mariani vote in the poorest departments of the region, in particular the Vaucluse. In richer areas, such as the Alpes-Maritimes, the RN vote is negatively correlated with the percentage of workers in the active population.

3

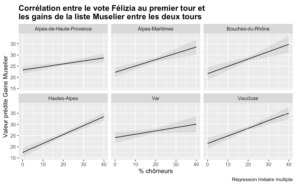

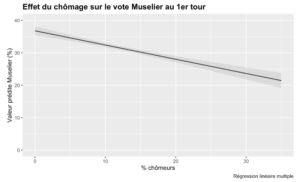

Conversely, the Muselier vote in the first round appears to be more concentrated in the richer communes. We observe a significant negative correlation according to the unemployment rate in the communes (see Figure g): the candidate of the right and the centre obtains his best results in the communes where unemployment is low; his scores are much weaker in contrast where unemployment is higher and this effect is relatively comparable in all the departments of the region.

Finally, with regard to the vote in favour of the left-wing list, we note a positive correlation with the unemployment rate in the commune, with, here again, differential effects according to the departments. The impact of unemployment on the Félizia vote is particularly notable in the Alpes-de-Haute-Provence where the candidate seems to have mobilised the more rural areas. Conversely, the vote in favour of the left is much weaker in the communes of the Vaucluse where the unemployment rate is higher and which, as we have emphasised, turned mainly towards the RN list led by Mariani (see Figure h).

These cleavages are blurred in the second round due to the nature of the Republican, united front against the RN list, even though the vote in its favour remains higher on average in the more working-class communes and those most affected by unemployment, such as the communes of the Vaucluse.

Conclusion

The regional elections of 2021 in the PACA/South Region have finally delivered a result quite similar to the major trends observed at the national level: despite promising polls, the RN has failed once again to take a region that seemed guaranteed to it. This failure in the PACA, echoed by the RN’s disappointments in several other major regions that were thought to be within its reach, shows the limits of the strategy of normalization of the party pursued by Marine Le Pen and deprives her of the great electoral foothold she had hoped for in the perspective of the 2022 presidential election.

As in 2015, the left is to face its very own brand new long march at the regional level towards regaining importance. Absent from the council for six years, its power in the region has fallen even further in 2021 and finds itself at rock bottom.

In the PACA, as in many other regions, the regional election has highlighted the organizational weaknesses of LREM and the lack of local presence of the presidential party, forced to forge an alliance with the classic right, a crucial keep-in-mind of a very likely (albeit not yet officialized) candidacy of Emmanuel Macron for a second term.

On the right, finally, the psychodrama that was played out around the constitution of the Muselier list testifies to the difficulties of LR to position itself today in a political space between LREM and the RN. The ability of the Republicans to solve this strategic equation will, without a doubt, be one of the keys to the presidential election and, as far as PACA is concerned, to the legislative elections.

Literature

Ivaldi, G. & Pina, C. (2016, 16 January). PACA, une victoire à la Pyrrhus pour la droite ?. Revue politique et parlementaire, numéro spécial « Élections régionales 2015 », n°1078.

Notes

- For the comparison with 2015, we added the scores of the lists led by Ch. Castaner (PS) and S. Camard (EELV).

- It is of course not possible to infer from this the individual behaviour of voters.

- These probabilities are calculated in a multiple linear regression at the level of the 946 communes of PACA, controlling for the effect of population density, the unemployment rate in the commune and the percentage of workers resident.

citer l'article

Christine Pina, Gilles Ivaldi, Regional election in Provence-Alpes-Côte d’Azur, 20-27 June 2021, Mar 2022, 62-67.

à lire dans cette issue

voir toute la revue