Regional elections in Romania, 9 June 2024

Cristina Stănuș

Associate Professor at the Lucian Blaga University of SibiuIssue

Issue #5Auteurs

Cristina Stănuș

Issue 5, January 2025

Elections in Europe: 2024

The second tier of local government in Romania

A two-tiered subnational government system is in place in Romania. Three categories of municipalities are present at the first tier, which corresponds to the LAU level. The counties (județe), which correspond to the NUTS3 level, are located at the second tier of local government (Bertrana et al., 2015) and are the closest analogue to a regional government level 1 . The population size and density of these counties are subject to significant variation due to the historical process of accommodating geography, ethno-cultural diversity, and various administrative traditions. The county councils (deliberative/legislative authorities) and the presidents of the county councils (executive authorities) are responsible for governing the counties. Romanian counties are characterized by a strong leader model in terms of horizontal power dynamics (between the president, council, and other relevant stakeholders), while being relatively weak in terms of vertical power relations with other levels of government

The county councils have been directly elected since 1996, using a proportional representation formula with closed party lists and electoral thresholds. The number of councillors is contingent upon the size of the county, with the entire county being considered a single district. The electoral threshold was introduced and subsequently raised to discourage smaller political parties and independent competitors, which was the most significant change to the electoral law during this period. The threshold for political parties in the 2024 county elections was 5% for parties, 7% for alliances of two political parties, and 8% for larger alliances. Independent candidates were required to accumulate a number of votes equivalent to the ratio of the total number of valid votes in the election to the total number of mandates. Special regulations were also in effect to guarantee the representation of national minorities (Székely, 2009).

The presidents of the county councils have been elected either indirectly (by the council in 1996, 2000, 2004, and 2016) or directly by the citizens (majority formula in 2008 and 2012 and plurality formula in 2020 and 2024) during the same period. Changes in the mode of election of county presidents were very much the results of political calculations by national parties, particularly before the 2016 elections, when there was a brief return to indirect elections.

The 2024 super-election year in Romania

Two factors have primarily shaped how the 2024 county elections were conducted. First, for the first time in 20 years, parliamentary, presidential, European, and local elections were all scheduled to take place in the same year. This has led to discussions on whether some of these elections should be held concurrently. While the official discourse of the national government centred on reducing the costs of running the elections, analysts suspected political calculations aimed at maximising the incumbents’ electoral performance. Second, the consequences of the pandemic on the electoral calendar persisted. In 2020, the mandates of local elected officials in office were extended, and the local elections were postponed from June to September. The mandates of officials elected in 2020 would, consequently, be expiring at the end of October 2024. This has disrupted the political routine. Since 1992, parliamentary and local elections have been held in the same year, with local elections usually scheduled in June and parliamentary elections in late November or early December. As county councils are the least visible level of government, there is an expectation that citizens largely vote according to their preference in parliamentary elections. Hence, national political parties have usually approached the results of county elections as an indicator of their expected performance in parliamentary elections and the basis for strategic campaign decisions (Dragoman & Zamfira, 2018).

These factors led to the decision to simultaneously hold local elections and European Parliament elections on June 9. Strategically, this was intended to help established parties with high numbers of local elected officials and strong local organisations (mainly the centre-left Social Democrat Party [PSD], the centre-right National Liberal Party [PNL], and the Democratic Alliance of Hungarians in Romania [UDMR]) to maximise their votes and fend off the challengers, especially the rising right-wing populist parties. Locally, it has created an unusual situation, with newly elected officials having to wait until late October to take office.

Other factors influencing these elections were the lowering of the legal thresholds for registering a new political party to just three members (in 2015) and the lowering of the thresholds for competing in elections (in 2020) (Székely, 2023). These could reasonably lead to an increase in the number of competitors in county elections, although they were not expected to seriously challenge the establishment parties.

Turnout in the 2024 local elections stood at 50.02 percent, a 4-percent increase from the 2020 local elections conducted during the pandemic. When compared to the pre-pandemic local elections, turnout was higher than in 2016 (48.43 percent) and lower than in 2012 (56.4). The turnout for the EP elections held on the same day was slightly higher (52.42 percent), most likely due to the participation of diaspora voters, as well as voters being away from their municipality of residence on election day.

More of the same? Political competition in the 2024 county elections

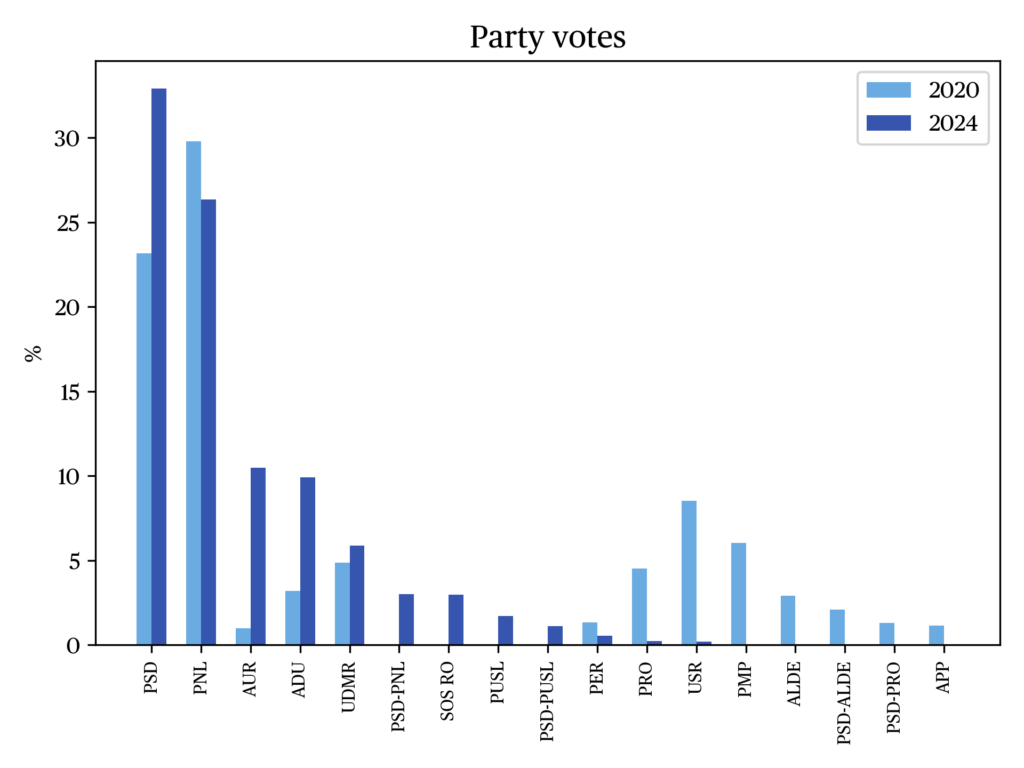

Romania has a nationalised local party system (Stănuş & Gheorghiță, 2022; Székely, 2023); hence, the lists competing for seats are usually the same from one county election to the next, with parties represented in the national parliament expected to remain largely unchallenged. Nevertheless, the 2024 election brought about a few changes in comparison to the 2020 election. Three different factors have contributed to a drop in the total number of competitors for seats in the county councils, from 83 to 52. First, there has been a decrease in the appetite of establishment parties to form local political or electoral alliances. In 2020, the seven parliamentary parties joined in 19 local alliances; in 2024, the same number of parliamentary parties joined in six local alliances. Second, the number of national minorities’ parties or organisations competing has decreased from ten in 2020 to six in 2024, likely due to their inability to pass the threshold and secure seats. Third, the number of independent candidates has also decreased from 15 in 2020 to just four in 2024, further confirming the gradual but consistent disappearance of independents in Romanian county politics. Simultaneously, the overall number of small national or local parties and alliances that participate in county elections has remained relatively consistent. Indeed, the aforementioned procedural changes have provided opportunities for small parties to compete. Moreover, the small number of independent candidates suggests county elections are very much a political parties’ game. If we look at this from the perspective of candidates for president of the county council, a similar picture emerges. The parliamentary parties have nominated candidates in all counties; smaller parties have managed to do so only in a fraction of the counties, while only two independents competed.

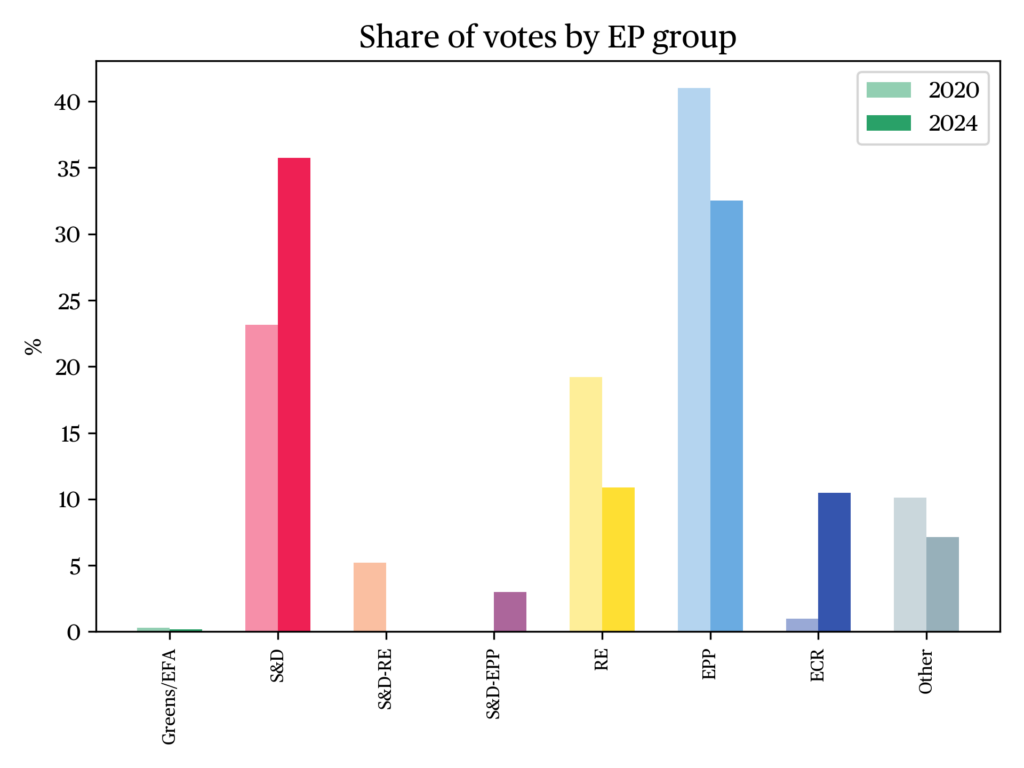

Beyond these numbers, three distinctive aspects of the political competition in these elections can be underlined. Firstly, the centre-left PSD (S&D) and the centre-right PNL (EPP), the ruling and largest political parties in Romania, have chosen to form an alliance for the simultaneous EP elections, while competing separately in local elections. Supposedly, the rationale behind this alliance was the necessity of countering the potential ascent of the far-right parties. This has raised questions about how the local organisations from both parties would conduct their electoral campaigns. Secondly, there was the question of whether the Save Romania Union (USR, Renew), a soft-touch populist party (Dragoman, 2021), would finally manage to gain more votes outside Romania’s largest cities and acquire better representation in the county councils. Thirdly, the election was an electoral litmus test for the Alliance for the Union of Romanians (Alianța pentru Unirea Românilor, AUR, ECR), the right-wing populist party that had unexpectedly earned entry into the parliament in 2020. In 2020, AUR was unsuccessful in local elections and had entered Parliament as a result of a territorially concentrated vote (Crăciun & Țăranu, 2023). Before the election year 2024, AUR has made significant efforts to build up its territorial network and to moderate its discourse.

Did the political centre hold? A brief look at the results

Prima facie, the results of the county electionsindicate that centrist national parties have maintained their grasp on county politics. Centrist parliamentary parties and local coalitions comprising at least one centrist parliamentary party have obtained 82.45% of the votes and 87.59% of the seats. This includes the 6.42% of votes, and respectively the 7.77% seats, obtained by the Democratic Alliance of Hungarians in Romania (UDMR, EPP). Some small organisations representing national minorities have collectively obtained less than one percent of the seats. Moreover, all the newly elected presidents of the county councils belong to the PSD, PNL, or UDMR.

| County | Total seats in council | Winner council | No. seats winner | Share of votes AUR-ECR | No. seats AUR-ECR | Seats needed for majority | No. of parties in council | Coalition needed for majority in council |

| Alba | 32 | PNL-EPP | 17 | 12.42% | 5 | 17 | 3 | No |

| Arad | 32 | PNL-EPP | 13 | 14.97% | 5 | 17 | 5 | Yes |

| Argeș | 34 | PSD-SD | 16 | 13.17% | 5 | 18 | 4 | Yes |

| Bacău | 36 | PSD-SD | 15 | 10.17% | 5 | 19 | 4 | Yes |

| Bihor | 34 | PNL-EPP | 18 | 5.14% | 2 | 18 | 4 | No |

| Bistrița-Năsăud | 30 | PSD-SD | 14 | 11.49% | 4 | 16 | 4 | Yes |

| Botoșani | 32 | PSD-SD | 15 | 7.77% | 3 | 17 | 3 | Yes |

| Brăila | 30 | PSD-SD | 18 | 11.28% | 4 | 16 | 3 | Yes |

| Brașov | 34 | PNL-EPP | 11 | 10.99% | 4 | 18 | 5 | Yes |

| Buzău | 32 | PSD-SD | 21 | 10.69% | 4 | 17 | 3 | No |

| Călărași | 30 | PSD-SD | 17 | 11.72% | 4 | 16 | 3 | No |

| Caraș-Severin | 30 | PSD-SD | 14 | 12.09% | 4 | 16 | 3 | Yes |

| Cluj | 36 | PNL-EPP | 13 | 10.35% | 4 | 19 | 5 | Yes |

| Constanța | 36 | PNL-EPP | 15 | 15.35% | 6 | 19 | 4 | Yes |

| Covasna | 30 | UDMR-EPP | 22 | 5.16% | 2 | 16 | 4 | No |

| Dâmbovița | 34 | PSD-SD | 22 | 8.25% | 3 | 18 | 3 | No |

| Dolj | 36 | PSD-SD | 21 | 9.29% | 3 | 19 | 4 | No |

| Galați | 34 | PSD-SD | 23 | 7.88% | 3 | 18 | 3 | No |

| Giurgiu | 30 | PNL-EPP | 17 | 8.33% | 2 | 16 | 4 | No |

| Gorj | 30 | PSD-SD | 16 | 14.05% | 5 | 16 | 3 | No |

| Harghita | 30 | UDMR-EPP | 24 | 2.60% | 0 | 16 | 4 | No |

| Hunedoara | 32 | PSD-SD | 16 | 17.31% | 7 | 17 | 3 | Yes |

| Ialomița | 30 | PSD-SD | 17 | 12.82% | 5 | 16 | 3 | No |

| Iași | 36 | PNL-EPP | 14 | 11.07% | 5 | 19 | 4 | Yes |

| Ilfov | 34 | Electoral alliance PSD-SD and PNL-EPP | 22 | 13.15% | 5 | 18 | 3 | No |

| Maramureș | 34 | PSD-SD | 15 | 6.36% | 2 | 18 | 5 | Yes |

| Mehedinți | 30 | PSD-SD | 18 | 8.81% | 3 | 16 | 3 | No |

| Mureș | 34 | UDMR-EPP | 14 | 8.21% | 3 | 18 | 4 | Yes |

| Neamț | 34 | PSD-SD | 16 | 9.27% | 4 | 18 | 3 | Yes |

| Olt | 32 | PSD-SD | 20 | 13.85% | 5 | 17 | 3 | No |

| Prahova | 36 | Electoral alliance PSD-SD and PPUSL-unaffiliated | 13 | 12.34% | 5 | 19 | 4 | Yes |

| Sălaj | 30 | PNL-EPP | 11 | 6.02% | 2 | 16 | 4 | Yes |

| Satu Mare | 32 | UDMR-EPP | 14 | 7.72% | 3 | 17 | 4 | Yes |

| Sibiu | 32 | PNL-EPP | 10 | 12.00% | 4 | 17 | 5 | Yes |

| Suceava | 36 | PSD-SD | 17 | 9.04% | 4 | 19 | 3 | Yes |

| Teleorman | 30 | PSD-SD | 18 | 9.65% | 3 | 16 | 3 | No |

| Timiș | 36 | Electoral alliance PSD-SD and PNL-EPP | 20 | 11.42% | 5 | 19 | 3 | No |

| Tulcea | 30 | PSD-SD | 13 | 15.44% | 6 | 16 | 3 | Yes |

| Vâlcea | 32 | PSD-SD | 19 | 9.41% | 3 | 17 | 3 | No |

| Vaslui | 34 | PSD-SD | 17 | 13.38% | 5 | 18 | 4 | Yes |

| Vrancea | 32 | PSD-SD | 13 | 9.02% | 3 | 17 | 4 | Yes |

However, the right-wing populist AUR, a parliamentary party since 2020, has obtained 11.70% of the votes and 11.88% of the seats. The other significant right-wing populist competitor, the S.O.S. Romania Party (SOS), a splinter group from AUR led by the controversial politician Diana Iovanovici-Șoșoacă, obtained 2.87% of the votes (226,949) and no seats. The results of AUR are below those obtained in the simultaneous EP elections (14.93 percent of the vote), yet they reflect a significant effort to develop local party organisations. Lacking this territorial structure, SOS obtained twice as many votes in the simultaneous EP election than in the county elections.

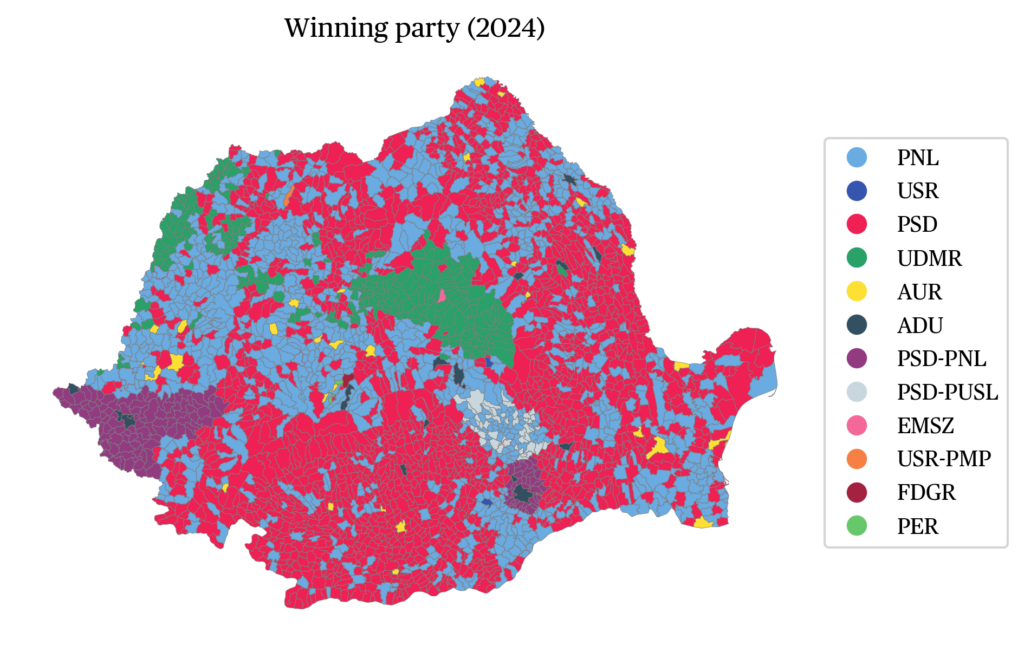

Long-term control of county politics by national parties has created specific territorial patterns, with the PSD controlling most of the area corresponding to the Old Kingdom of Romania and the PNL and UDMR controlling most of the other counties. This is easily observable by looking at the party affiliation of the presidents of the county councils. Thus, in 2020, the PNL was successful in eight Old Kingdom counties and ten in the rest of the country, while the PSD won 18 Old Kingdom counties and only two in the rest of the country (Székely, 2023). In 2024, the PNL was successful in four Old Kingdom counties and seven counties in the rest of the territory, while the PSD won 20 counties in the Old Kingdom and four in the rest of the territory. Two counties, one in the Old Kingdom and one in the rest of the country, were won by a candidate jointly supported by the PSD and PNL. The UDMR won four Transylvanian counties. These results clearly indicate a subpar performance of the PNL, especially in Old Kingdom counties.

Beyond the aggregated votes at the national level, a new reality has emerged in many parts of the territory. The PSD and PNL, separately, together, or in alliance with smaller parties, have gained representation in all counties. However, in the last 20 years, the routine of Romanian county politics has usually also involved the presence of smaller centre-left or centre-right parties (typically splinter groups from the PSD and PNL) in county councils. Sometimes these smaller parties participated in building majorities in the county councils. In 2024, the right-wing populist AUR replaced these parties in the county councils after they failed to pass the electoral threshold. In 18 counties, only three parties gained seats: the PSD, PNL, and AUR. AUR has also gained representation in all but one of the remaining counties. As a majority needs to be formed in the county council to appoint the vice-presidents of the council (who would then exercise executive tasks delegated by the president), AUR has gained significant coalition potential, thus cementing its position in the Romanian party system. Moreover, the USR has not managed to break its large-urban mould and has only gained seats in 15 counties. UDMR has, as usual, obtained seats in 11 counties where significant groups of ethnic Hungarians live. The ability of AUR to replace the smaller parties should have been suggestive to the other parties of the continuous rise of the far-right in the preferences of the Romanian electorate, potentially leading to changes in strategy. As of early 2025, it is still unclear whether this has happened.

The data

References

Bertrana, X., Egner, B., & Heinelt, H. (Eds.) (2015). Policy Making at the Second Tier of Local Government in Europe: What Is Happening in Provinces, Counties, Départements and Landkreise in the On-Going Re-Scaling of Statehood? London: Routledge.

Crăciun, C., & Țăranu, A. (2023). AUR – The Electoral Geography of Romanian Conservative Nationalism. Political Studies Review.

Dragoman, D. (2021). “Save Romania” Union and the Persistent Populism in Romania. Problems of Post-Communism, 68(4), 303–14.

Dragoman, D., & Zamfira, A. (2018). 2016 Romanian Regional Elections Report. Regional & Federal Studies 28(3), 395–408.

Stănuş, C., & Gheorghiță, A. (2022). Romania: A Case of National Parties Ruling Local Politics. In A. Gendźwiłł, U. Kjær, & K. Steyvers (Eds.), The Routledge Handbook of Local Elections and Voting in Europe. London: Routledge.

Stănuş, C., & Pop, D. (2011). Romania. In H. Heinelt & X. Bertrana (Eds.), The Second Tier of Local Government in Europe: Provinces, Counties, Départements and Landkreise in Comparison (pp. 223–41). London: Routledge.

Székely, I. G. (2009). Reprezentarea Minorităţilor În Consiliile Locale. Sfera Politicii 138, 38–47.

Székely, I. G. (2023). The 2020 County Elections in Romania: More Nationalization, Less Regionalization. Regional & Federal Studies 33(4), 555–67.

Notes

citer l'article

Cristina Stănuș, Regional elections in Romania, 9 June 2024, Sep 2025,

à lire dans cette issue

voir toute la revue