Issue

Issue #2Auteurs

Théophile Rospars , Jean-Toussaint Battestini , Charlotte von Born-Fallois , Michał Ekiert , Juuso Järviniemi , Charlotte Kleine

21x29,7cm - 167 pages Issue 2, March 2021 24,00€

Elections in Europe : June 2021 – November 2021

Introduction

The past electoral semester has been rich in new political developments both quantitatively, by the number of elections that have taken place, and qualitatively. In this issue, we will review these dynamics from a European perspective, whilst paying special attention to local and regional specificities.

Following this Continental Review prepared for you by BLUE’s editors, you will find analyses of all individual elections of the past period, written by experts of the various local, regional and national arenas.

At the municipal level, two major Italian cities, Rome and Milan, have experienced a power shift towards Social Democracy. These two elections will be analysed by Sofia Marini, a researcher at the University of Vienna and a member of BLUE’s editorial team.

Various regional elections were held during the past semester. In France, the left-right cleavage remains dominant at the regional level despite both the far-right and President Macron’s attempts to overcome it. The June 2021 regional elections will be commented on and put into perspective in the most comprehensive series of analyses of French regional elections ever published, combining contributions by researchers from all over the country with short analyses by members of BLUE’s editorial team.

In Germany, a number of regional elections have prepared the ground for the federal election held in September. In the Saxony-Anhalt Landtag election, the outgoing Minister-President was able to capitalize on local issues to confirm the position of Christian democracy in this East German state. Christian Stecker from the Technical University of Darmstadt will analyse this election.

The elections to the Landtag of Mecklenburg-Western Pomerania and the Chamber of Deputies in Berlin strengthened the position of the centre-left parties and the liberals as the result of both local and federal dynamics. These results will be presented by Erik Baltz, Sophie Suda and Maximilian Andorff-Woller from the University of Greifswald on the one hand and François Hublet, BLUE’s editor-in-chief, on the other.

In Upper Austria, in the wake of the Ibiza Gate scandal, the far right lost ground to a new protest party opposing measures against the Covid-19 pandemic, while the other parties consolidated their positions. Harald Stöger of the University of Linz will analyze the outcome of the vote.

In Calabria, the governing center-right coalition was strengthened, while the centre-left coalition lost ground to an unexpected outsider, the mayor of Naples. Francesco Truglia, from the University of Rome, will analyse the consequences of this three-way competition.

This semester ended with the Danish regional elections. In Danish regions, the conservatives made very substantial gains at the expense of the Social Democrats, who govern at the national level. Ulrik Kjær, from the University of Southern Denmark, will discuss the results of this election.

At the national level, Bulgarians were called to vote for their parliament for the second and third time in a year, confirming the weakening of the dominant center-right party in favour of new citizen movements. You can learn more about the renewal of the country’s political spectrum in a piece by Dragomir Stoyanov, from the University of Sussex, and in a short analysis by BLUE’s editorial team.

In Germany, Angela Merkel’s former vice-chancellor, Olaf Scholz, led his governing Social Democrats to victory in the September 2021 federal election, despite the party’s low approval rates during the last four years. Scholz capitalized on the success of the Greens and Liberals to end a political era dominated by Christian democracy. The ballot will be presented by Andrea Römmele from the Hertie School of Governance.

The Czech Republic has entered a new political era after oligarch Babis lost his grip on national politics. Tomáš Weiss from Charles University in Prague will discuss the political recomposition in the country.

Finally, two important partners of the European Union and EFTA countries, Norway and Iceland, have held general elections, the outcome of which will be presented by Stine Hesstvedt from the Oslo Institute for Social Research and Eva Heiða Önnudóttir from the University of Iceland.

But first, in order to better understand the continental implications of these analyses, we have prepared a short summary of last semester’s developments

Evolution of the results of European groups

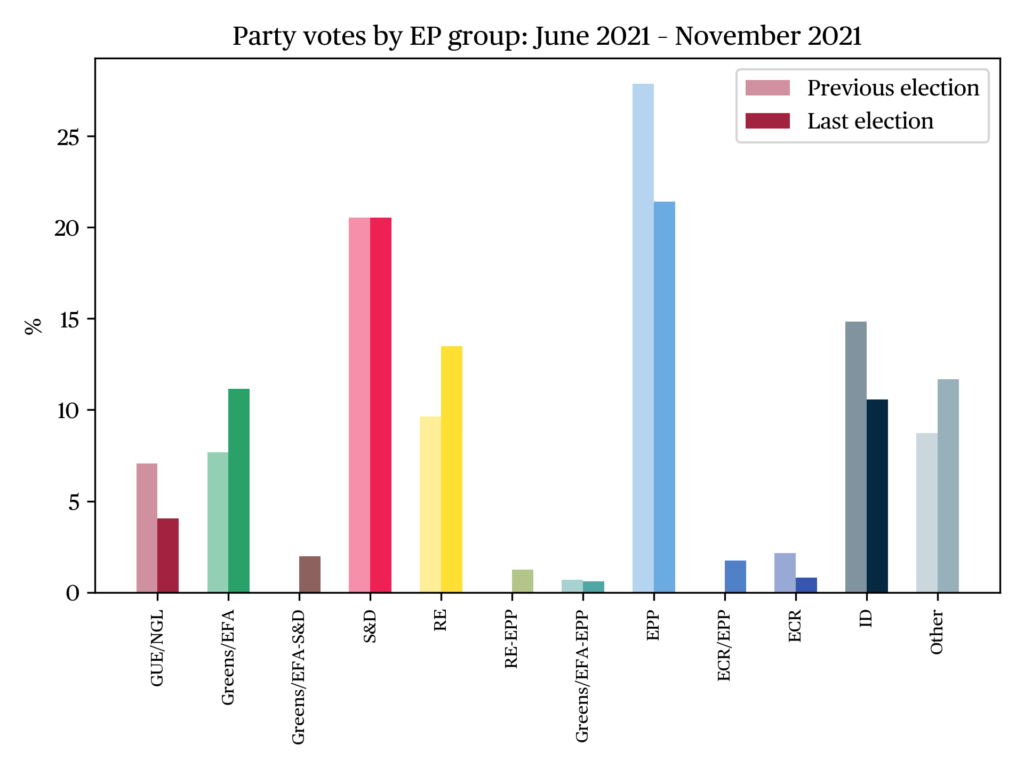

This biannual review of European elections provides an ideal opportunity to study the overall electoral performance of European party families. Following the methodology established in the previous issue of BLUE, political parties are grouped according to their membership in a political group in the European parliament, or, if they do not formally belong to any group, according to the political group to which they appear to be closest .

The parties of the far-right ID group were the biggest losers of this electoral semester, with an average decline of 4 percentage points [pp]. Only in Rome did ID see its vote share increase significantly (+4 pp), while everywhere else the group suffered losses which even approached 15 pp in several French regional elections.

The conservative and Eurosceptic ECR group is stable at -1 pp on average, while EPP/ECR alliances are gaining 2 pp. The ECR made significant gains in the Italian municipal elections and were involved in the victory of the SPOLU coalition in the Czech Republic, an alliance of EPP and ECR parties. Elsewhere, ECR’s positions are stable or slightly declining.

The EPP’s center-right and traditional right-wing parties lost an average 7 pp. This is due to strong gains in Saxony-Anhalt and Denmark (+7 and +8 pp), offset by strong losses in Bulgaria, Germany (Bundestag) and Milan, mixed success in the French regional elections, and a generally stable or declining position in other elections. In the Czech Republic, some of the EPP’s votes went to the SPOLU alliance with the ECR (+2 pp at aggregate level).

The centrist RE group and related parties, which suffered the largest losses in the previous six months, is now clearly on the rise, with a positive balance of 4 pp. This is mainly due to its entry into French regional council and the emergence of new political formations in Bulgaria.

The Greens/EFA recorded an average gain of 3 pp this semester, confirming their positive momentum. The evolution of Green and regionalist scores is almost unanimously positive (except in two French regions and one Danish region), although they do not always reach the expected scores, especially in Germany. In addition, there was a gain of about 2 pp for S&D-Green alliances in the French regional elections.

The Social Democrats in the S&D group are stable (0 pp). Major victories in Rome (+24 pp) and Milan (+11 pp) and good results in the German federal elections (+5 pp) as well as in Mecklenburg-Western Pomerania (+9 pp) are counterbalanced by a stable or declining trend in all other territories surveyed.

The radical left-wing GUE/NGL group continues its decline, with -3 pp on average. The only significant gains (+3 pp) were recorded in the Danish regional elections.

Non-inscrit parties gained 3 pp this semester, with significant losses in Bulgaria (-8 pp), Milan (-10 pp) and Rome (-39.1 pp), offset by gains in Calabria, Iceland, Berlin and Upper Austria.

Parties entering and exiting regional and national parliaments

The regional and national elections of the second half of 2021 were characterized by the eviction of some parties and the emergence of new ones. During the French regional elections, no major political upheaval took place, except for the unprecedented low turnout (around 34%). La République en Marche (LREM, RE) and its allies entered the regional councils of Burgundy Franche-Comté, Brittany, Centre-Val de Loire, Île-de-France, Normandy and Pays de la Loire. However, beyond obtaining regional parliamentary representation, President Macron’s party had only limited electoral success, failing to win a single regional presidency. In addition, the party lost its representation in the Corsican Assembly, as its former candidate, Jean-Charles Orsucci, who had not even sought the nomination of LREM in this election, did not reach the qualification threshold for the second round.

After having to withdraw their list between the two rounds of voting in 2015 to prevent the victory of the Front National (ID), the Hauts-de-France left managed to get back into the regional council, forming a coalition led by the Ecologists and involving the Socialist Party (PS, S&D), Unbowed France (GUE/NGL) and Génération.s (S&D).

In Occitania, Unbowed France lost its representation in the regional council by failing to qualify for the second round, with only 5% of the vote in the first round.

Finally, in Corsica, the region where the turnout was the highest (at 58%), a new pro-independence party has entered parliament, while LREM lost its parliamentary representation. In the same time, the historical pro-independence party of Corsican nationalists, Corsica Libera, led by the incumbent president of the Corsican assembly, has nearly disappeared. The party was eliminated after the first round of voting, and the merger of part of his list with the rival pro-autonomy party of the outgoing president of the regional government, Gilles Simeoni, obtained only one seat, compared with 14 in the previous term. The pro-independence party Core in Fronte, which adopts a more radical stance vis-à-vis the French state, won six seats.

In Germany, the federal elections of September 26, 2021, saw the Danish minority party of Schleswig-Holstein win one seat in the Bundestag. On the same day, the Landtag of Mecklenburg-Vorpommern elected its regional parliament, allowing both the Greens (Greens/EFA) and the liberal FDP (RE) to gain representation with 5 seats each, mostly at the expense of the CDU (EPP) and the far-right AfD (ID), which both lost 4 seats. In June 2021, the Landtag elections in Saxony-Anhalt also saw the liberal FDP enter the regional parliament with 7 seats.

In Austria, the regional parliament in Upper Austria was also up for re-election on September 26. The anti-vaccine and anti-lockdown party Movement for Fundamental Rights (MFG, NI) won 3 seats in the regional parliament. The classical liberal NEOS (RE) also entered parliament with 2 seats.

The Czech Republic’s parliamentary elections in October 2021 saw the Social Democratic Party (S&D) and the Communist Party (GUE/NGL) leave the national parliament. Both parties lost the 15 seats they won in the last elections in 2017.

In Calabria, the early regional elections in October 2021 allowed the 5-Star Movement (M5S, NI) to win two seats, allowing it to obtain parliamentary representation. The “Democracy and Autonomy” coalition led by Luigi de Magistris, an alternative center-left candidate, also won 2 seats, giving it a seat in the regional parliament.

In Denmark, the November 2021 regional elections in the country’s five regions were characterized by the loss of representation at the regional level by the center-left Alternative party (Å, GUE/NGL) and the entry of the far-right Eurosceptic New Right party (D, NI).

Bulgaria’s third early elections in November 2021 saw the Europhile, anti-corruption party “We Continue the Change” (PP, NI) enter parliament with 67 seats, at the expense of the “Stand Up BG” (NI) party, which lost its 13 seats and left parliament after being blamed for the failure to form a government. The Eurosceptic “Revival” (NI) party entered parliament with 13 seats.

Outside the Union, the Norwegian parliamentary elections of September 2021 allowed the Patient Focus party (NI) to win a seat. This small party is supporting the expansion of the Alta hospital in Finnmark county, in the North of Norway.

The September 2021 parliamentary elections in Iceland did not result in any new parties entering or exiting the national parliament.

Turnout

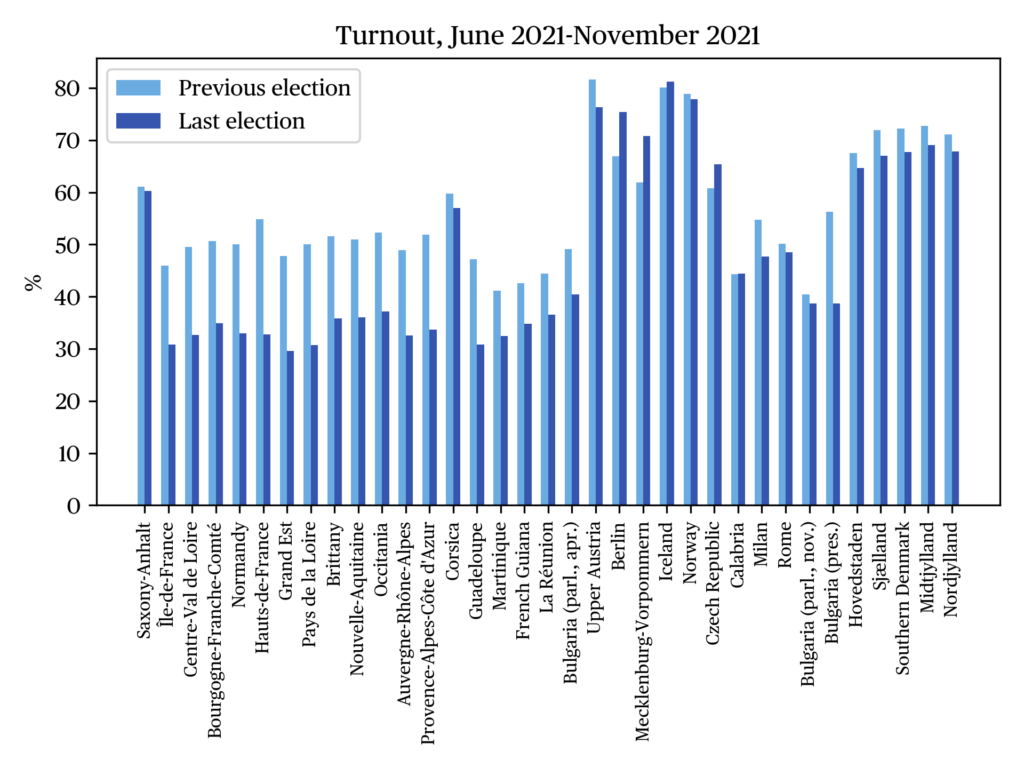

In the regional elections in metropolitan France, abstention reached record lows. In all regions, drops by over 15% were recorded. In Hauts-de-France, turnout fell from 54.8% — the highest rate in the last elections in 2015 — to 32.8%, a drop of 22%. Turnout was lowest in Grand Est, where less than a third, or 29.6%, of registered voters cast a ballot.

In Corsica, however, turnout remained stable, dropping by 2.7% (59.7% in 2015; 57% in 2021). This can be partly explained by a strong nationalist mobilisation.

In the overseas departments, collectivities and regions, participation was significantly lower than in mainland France and Corsica in 2017, with 41.1% of the population participating in Martinique and 47.2% in Guadeloupe. The decline was proportionally less dramatic than in the metropolitan regions — between -8.7% in Martinique and -7.9% in Reunion. The turnout in 2021 was therefore similar in the overseas regions and collectivities and in mainland France.

The tumultuous election year in Bulgaria saw sharp falls in turnout. The first parliamentary elections were held in April 2021 (see BLUE #1). After failing to form a government, the national assembly was dissolved, and new elections were held in July 2021. In this election, turnout dropped by 8.7%. This was due to several factors: voter discontent, efforts by the interim government to curb illegal voting practices, July holidays, and, finally, the introduction of a new electronic voting system that may have deterred some older voters.

However, the July 2021 election did not produce a winner either, so new parliamentary elections were held in November 2021. It coincided with the presidential election. This double election day did not produce a clear winner either. A second round was necessary to re-elect President Rumen Radev. Turnout in the first round and in the parliamentary election was 38.7%, the lowest in 30 years. In the second round of the presidential election, a new record low was recorded, with only 33.65% of the population turning out to vote.

In Germany, the effect of the “super election year” was clearly reflected in the turnout in the Berlin Senate elections (+8.5 pp, at 75.4%) and in Mecklenburg-Vorpommern (+8.9 pp, at 70.8%), where a regional election was held on the same day as the Bundestag elections.

In Saxony-Anhalt, the elections happened on 6 June. Turnout was down by only 0.8%: in 2017 it was 61.1% and in 2021 60.3%.

Two EFTA countries, Norway and Iceland, held parliamentary elections in September 2021. In Norway, turnout decreased by 1.1 pp to 77.8%, while in Iceland turnout increased by 1.1 pp, with 81.2% of the population voting.

In Upper Austria, the 2016 Landtag elections were marked by a strong polarisation around the migration issue, and the turnout was correspondingly high: 81.6% of the electorate turned out to vote. In September 2021, it was the Covid crisis and the issue of compulsory vaccination that mobilized the electorate, however a drop by 5.3 pp was still recorded: 76.3% of Upper Austrians voted.

In Calabria, the turnout in the early election was stable, increasing by 0.1% compared to the last election in 2020. In 2014, the turnout rate was similar. In Milan, where the election had been postponed to October 2021 due to a peak in infections in the spring, trnout fell by 7% — in 2016, 54.7% of voters had cast their ballots, in 2021, 47.7%. In Rome, turnout fell slightly, by 1.6%, to below 50% at 48.5%.

In the Czech Republic, turnout increased by 4.6%. In 2017, 60.8% of the electorate voted, in October 2021 the figure was around 65.4%.

On 16 November 2021, members of 95 municipalities and 5 regional councils were elected in Denmark. Turnout decreased in all five regions, ranging from -2.8 pp to -4.5 pp, reaching a turnout of between 64.7% and 72.7%.

Germany’s major election year

Germany’s “super election year” (Superwahljahr) ended on September 26, 2021, when elections were held for the German Bundestag and two Länder, Berlin and Mecklenburg-Vorpommern. Thuringia was also due to elect a new Landtag on the same day, but there was no (two-thirds) majority to dissolve parliament, as this would have required the votes of the AfD (ID).

The federal elections brought an end to the “Grand Coalition” of Christian Democrats (CDU/CSU, EPP) and Social Democrats (SPD, S&D). Despite major gains, it was not the Greens but Olaf Scholz’s SPD that came out on top in the 2021 federal elections: with 25.7%, the Social Democrats overtook the Christian Democrats (24.1%) after a long neck-and-neck race between the two parties during the election campaign. The Greens saw their number of votes increase by 5.8 pp and came third with 14.8%, missing their goal of making their candidate, Annalena Baerbock, Angela Merkel’s successor.

The growing influence of the Greens, which this time was not sufficient to win against the Social Democrats, is a trend that could also be observed in the regional elections:

In Berlin, affordable housing was the dominant issue in the election campaign after the previous government’s rent control law (“Mietpreisbremse”) was declared unconstitutional by the federal constitutional court. Nevertheless, the citizens of Berlin confirmed their confidence in the previous red-red-green government: the Social Democrats lost slightly, but still managed to take first place with 21.4%, while the Greens even increased their results to 18.9%. SPD’s Franziska Giffey also managed to be elected mayor of Berlin.

In Mecklenburg-Western Pomerania, the SPD and its candidate Manuela Schwesig are the big winners in this year’s elections: With 39.6%, the Social Democrats increased their score by 9 pp — mostly at the expense of the Christian Democrats, who could only win 13.3%. For the first time since 2011, the Greens managed to break the 5% barrier and entered the Landtag with 6.3%.

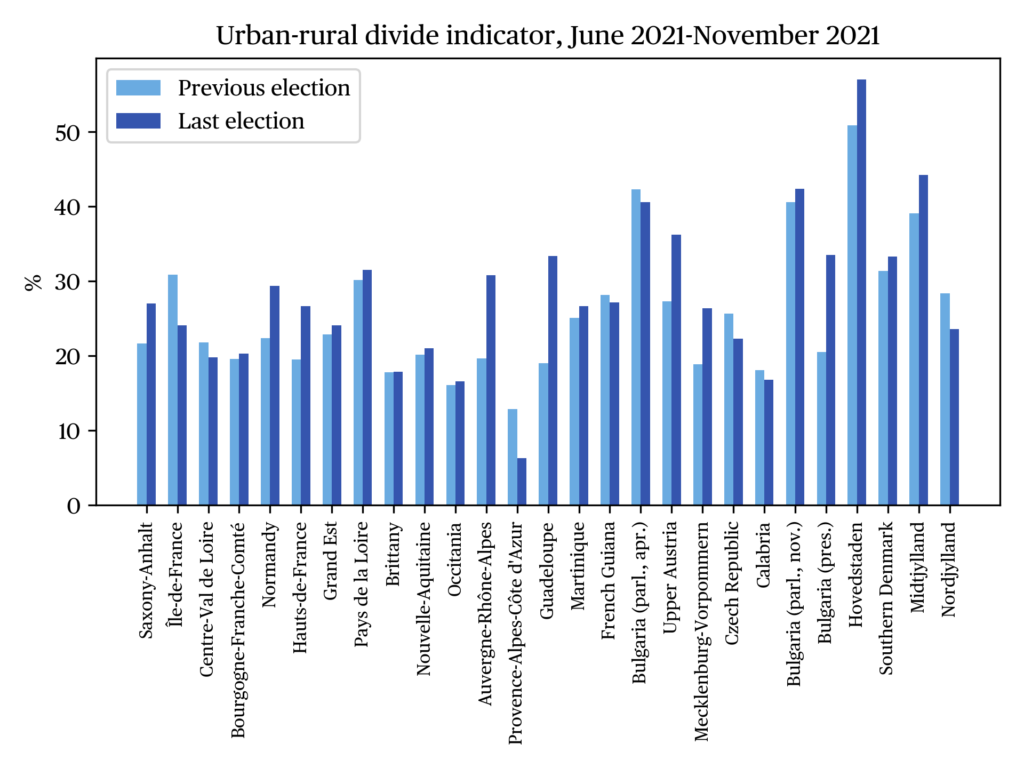

Urban-rural divide

BLUE constructed an indicator to measure the polarization of the vote between urban and rural areas. Given the aggregate score u1, …, up of the parties in the urban electorate and the aggregate scores r1, …, rp of these same parties in the rural electorate (in percent), we consider

1/2 ( |r1 – u1| + … + |rp – up| ).

The result is a percentage that varies between 0% and 100%, where 0% means that the shares of the different parties in the urban and rural electorates are identical, and 100% means that the urban electorate votes for entirely different parties than the rural electorate.

In the majority of elections, the rural/urban divide has widened. Hovestaden, the Danish region where Copenhagen is located, had already experienced the largest divide in previous elections; the divide increased by a further 6.1 pp in the 2021 election to well over 50 per cent: more than half of the urban population votes differently from those living in rural areas. The divide has also widened, albeit less dramatically, in two other Danish regions, Midtjylland and Southern Denmark, in contrast to Nordjylland where the gap has narrowed.

In France, the gap has widened in most regions, except in Île-de-France, Guyana, Centre-Val-de-Loire and Provence-Alpes-Côte-D’azur. This last region contains large cities and agglomerations, notably Marseille. It is by far the region where the divide is the narrowest. This divide has even decreased by 6.6 pp between the last regional election in 2016 and the one in June 2021. This can be explained in part by the increased presence of the Rassemblement national in major cities — a rather atypical situation in the French context. The largest increases of our indicator were recorded in Guadeloupe (+14.4 pp) and Auvergne-Rhône-Alpes (+11.1 pp).

In Saxony-Anhalt and Mecklenburg-Western Pomerania, the cleavage increased by 5.3 pp and 7.5 pp respectively. The increase was even more pronounced in Upper Austria, where the indicator rose by 8.9 pp.

In the July parliamentary election in Bulgaria, the urban-rural divide indicator fell by 1.7 pp, but in November it rose again by 1.8 pp. The contrast was much more striking in the presidential election, where the divide widened by 13 pp to over 30 percent.

In the parliamentary elections in the Czech Republic, the divide narrowed by 3.4 pp. In Calabria, it also decreased slightly, by 1.3 pp.

Socio-economic determinants of the vote

Table d presents the results of a least squares model estimating the effect of eight socio-economic factors on the electoral shares of the different European political groups, aggregated at the NUTS 3 level.

All else being equal, the parties of the left-wing GUE/NGL group and the Greens/EFA group performed better in densely populated areas, while the parties of the nationalist ID group performed worse in these areas. High GDP growth in the region is associated with a positive effect on the vote share of the Green/EFA parties, and a negative effect on the GUE/NGL and ID parties. With the other parameters fixed, however, an already existing high GDP per capita was associated with a higher vote for ID, and a lower vote for the Green/EFA parties.

The rate of net migration in the region has a significant effect on the scores of several parties. RE’s liberals perform better in regions with high immigration, while conservative parties (REC and EPP) enjoy less support in these regions. On the other hand, liberal parties performed less well in regions with a high level of education.

| Group | Positive effect | Negative effect | R² |

| GUE/NGL | Pop. density*** | GDP growth*** | 0.92 |

| Greens/EFA | Pop. density*** GDP growth*** | PIB/capita PPP*** | 0.93 |

| S&D | 0.47 | ||

| RE | Net migr.*** | Univ. degree** Unemployment* Median age* | 0.82 |

| EPP | Net migr.* | 0.64 | |

| ECR | Net migr.*** | 0.92 | |

| ID | PIB/capita PPP* | Pop. density*** Birth rate* GDP growth*** | 0.94 |

Controls: member states, source : Eurostat, last available year

Parties considered close to a group have been counted together with this group.

205 NUTS 3 regions: 5 AT, 28 BG, 14 CZ, 23 DE, 11 DK, 100 FR, 1 IS, 1 IT, 18 NO

Notes:

a) The data for the Bundestag elections have not yet been published at the district level and could therefore not be included in the calculation.

b) Lists mixing several EP groups were ignored.

d • Results of the statistical model at NUTS 3 level

Autonomy — independence

The Corsican regional elections in June 2021 saw a consolidation of Gilles Simeoni’s power. Simeoni, the leader of the autonomist Femu a Corsica (FaC, Greens/EFA), had previously chaired the Corsican Executive Council thanks to an autonomist-nationalist coalition. He ran on its own party list in 2021, this time winning an absolute majority of seats in the Corsican Assembly.

Overall, nationalist and autonomist parties are increasingly dominant in Corsican politics. Among the unionist movements, only a right-wing coalition participated in the second round of the regional election, winning 32 per cent of the vote and 17 of the 64 seats. All other seats are now held by nationalists, who sat on both the government and opposition benches. Autonomist and nationalist politics are increasingly dominant, but the differences between the different currents of the movement are more visible than before.

While Corsica has a strong tradition of regionalist politics, in Norway the representation of regional interests in the national parliament is more marginal. However, in 2021, the Pasientfokus movement (PF, NI), which advocates for the expansion of the hospital in the town of Alta, in the northern Finnmark region, won a seat in the Storting. The party received more than 40 per cent of the vote in Alta, and won a seat despite having only 0.2 per cent of the vote nationally. PF is not the first regional party in Norwegian history: in 2013, a party called “Hospital for Alta” had campaigned in the elections without winning any seats. In the Norwegian context, the defense of regional interests in the North focuses on social service provision in remote areas, rather than on political autonomy.

In the German parliamentary elections, the Federation of South Schleswig Voters (SSW, Greens/EFA) won a seat in the Bundestag for the first time since 1949. Representing the interests of the Danish minority, the party won one of the seats in the northern state of Schleswig-Holstein. The party’s campaign platform included calls for infrastructure funding for the region and lower electricity prices. Thus, Germany presents an example of regionalist voting based on economic interests, complemented by the promotion of minority interests.

Anti-corruption movements

In 2021, many elections in Central and Eastern Europe have triggered majority change following citizens’ dissatisfaction with the level of government corruption. This has led new political movements, often recombining with the old opposition, to take the lead in change. While this may not seem important for countries such as Germany, the Netherlands and France, for places such as the Czech Republic, Bulgaria and Moldova this may be the decisive aspect leading to the willingness to change government. When anti-corruption movements manage to rise to the top and a broad unity of political forces is achieved, dramatic changes can occur. In the three countries we have mentioned, the political scene has been reshaped accordingly.

Andrej Babiš, one of the richest tycoons in the Czech Republic, and the now former Czech prime minister, came to power in 2017 with his ANO (ALDE) party, whose name literally means ‘yes’ in Czech. After his electoral victory, Babiš’s catch-all party gained a strong foothold and began facing levels of dissatisfaction similar to previous governments, especially as it allied itself on an ad-hoc basis with the otherwise isolated ČSSD (S&D). Dissatisfaction with the overwhelming figure of Babiš, a wealthy man perceived by opponents as the natural ferment of corruption, combined with his mismanagement of the pandemic, made for a powerful mobilization of the opposition. The classic centre-right party, often perceived as dull by public opinion, reinvented itself as SPOLU (“Together”, ECR/EPP), while the Mayors and Independents (EPP) and Pirates (Greens/EFA) formed a second opposition coalition on a more alternative and centrist platform. Despite ANO coming out on top, runner-up SPOLU eventually obtained the post of prime minister after forming a coalition with the Mayors and Pirates.

“We Continue the Change” (PP, NI), the centrist party of Kiril Perkov and Asen Vasilev, the ministers of economy and finance in Bulgaria’s interim government, defeated GERB (EPP), which had been in power for almost a decade and a half. The two previous parliaments, elected in April and July, failed to agree on a government and were dissolved after a few weeks. During the election campaign there were many attempts to trade votes, with over 500 preliminary investigations and 2,000 official warnings reported, which mostly involved GERB and the DPS (RE). Petkov and Vasilev, who between May and August helped expose numerous embezzlements and corrupt behaviours of former Prime Minister Boyko Borisov’s government, founded their party in September. Their main slogan became the fight against corruption and judicial reform.

In Moldova, President Maia Sandu and her Action and Solidarity Party (PAS, ~EPP) seek to rebuild the country on the basis of anti-corruption, moral revolution and pro-Europeanism. In the July parliamentary elections, PAS won an independent majority in parliament. The party dominated the center and the pro-Western part of the political scene. The Democratic Party (~S&D), which was in power and co-governed from 2009 to 2021, the formations calling for reunification with Romania and the Dignity and Truth Party (~EPP), which has recently cooperated with PAS, did not enter parliament. Moreover, the elections gave a very weak result for the pro-Russian forces. The weakness of the opposition and the strong popular support currently give PAS significant political leeway.

This confirms a trend already observed in BLUE’s first issue: across Eastern Europe, new political formations are being created with a focus on pro-Europeanism and more effective governance, but with less emphasis on the classic left-right divide.

Role of the diaspora

While the diasporas of the Balkan countries have traditionally played an important role in domestic politics, their influence has significantly increased in recent years. In the Bulgarian elections of July 2021, for the first time, the overseas vote proved decisive, depriving GERB of the much-desired top spot. A record number of overseas polling stations, 750, were set up for this election. Although the Bulgarian community abroad has been voting for 30 years in other countries, this right is still controversial. For the first time, there were more polling stations in Britain than in Turkey. While, in Bulgaria, the vote of the diaspora has long been a way for the DPS (RE), the traditional party of the Turkish minory, to increase their vote shares generational change makes this strategy less powerful. Instead, vote from abroad is often a way for the young and frustrated to express their disappointment following a decade of GERB government. 2021 redefined the political role of Bulgarian emigrants, placing this demographic group at the heart of the country’s policy in the future.

Similarly, Moldova is following a trend of reaching out to the diaspora living in EU countries, perhaps in the hope that they will become a driving forces in the adhesion process alongside the country’s much-desired transformation. While there are more polling stations abroad than ever before, the influence of the diaspora is not as pronounced as in Bulgaria.

In other European countries which recently held elections, the influence of the diaspora is mostly negligible, often due to procedural limitations on voting (e.g. in the Czech Republic) It remains to be seen whether diasporas can provide an influx of qualified cadres for the new governments, which often emerge from mobilization and lack established personnel.

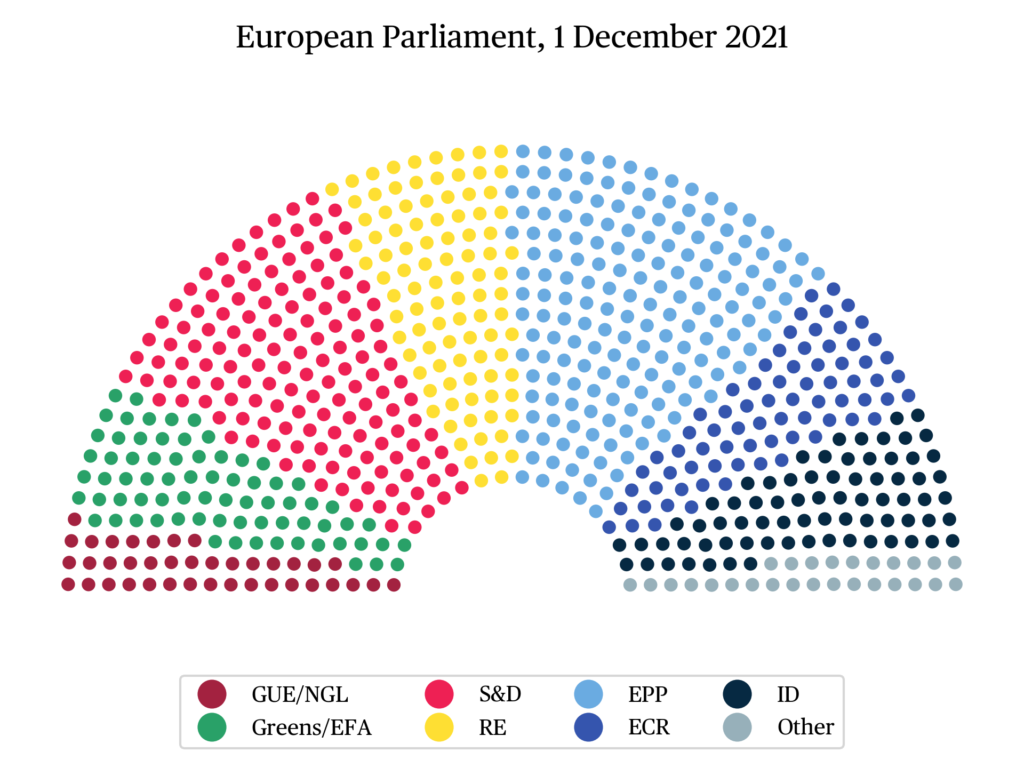

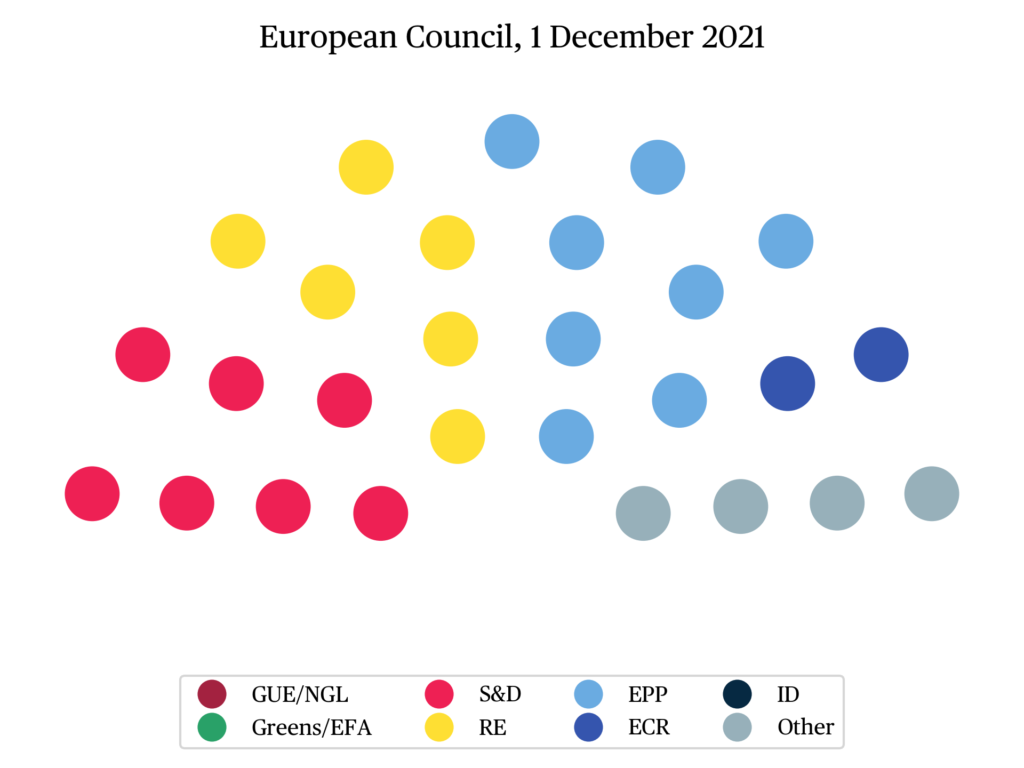

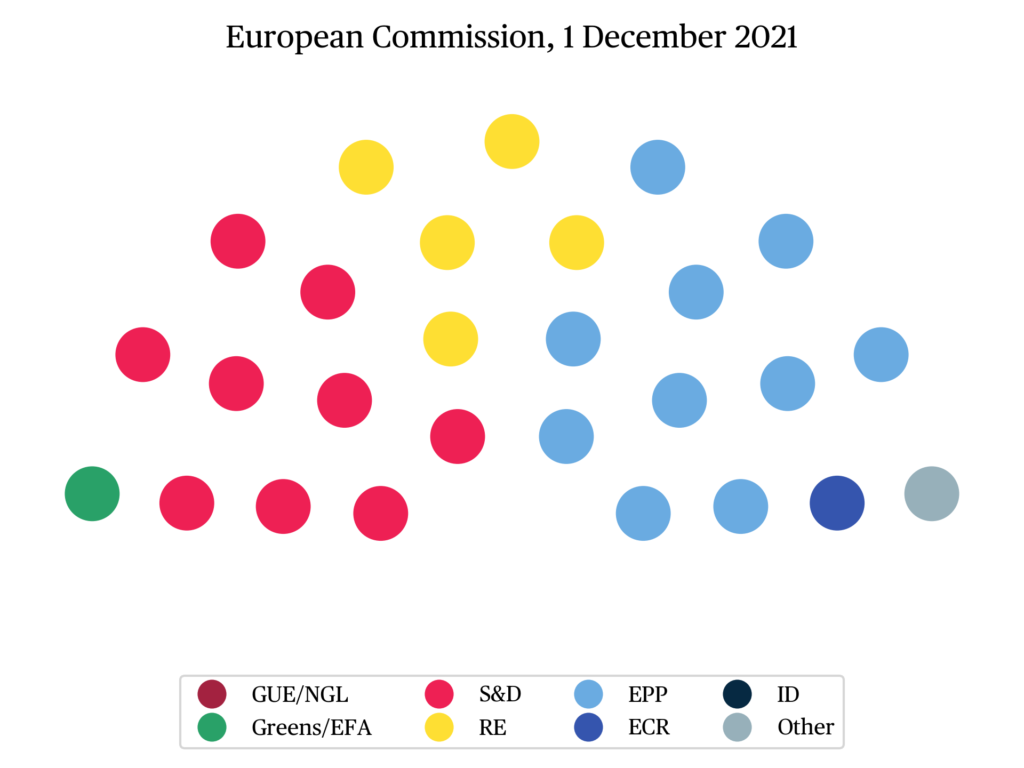

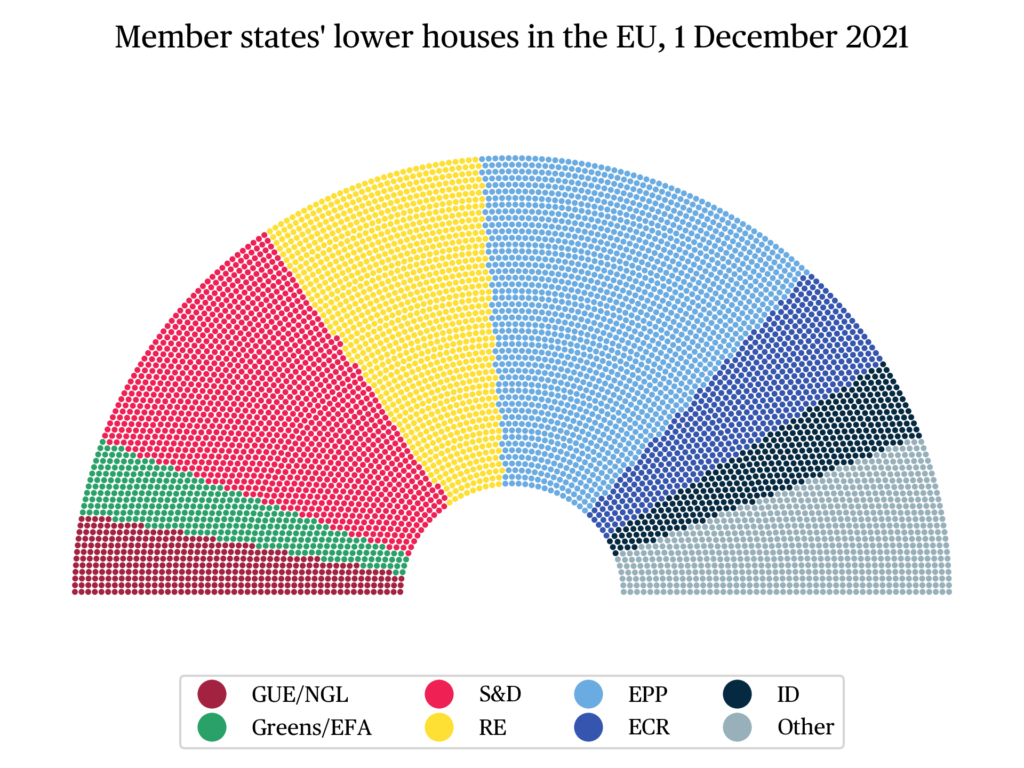

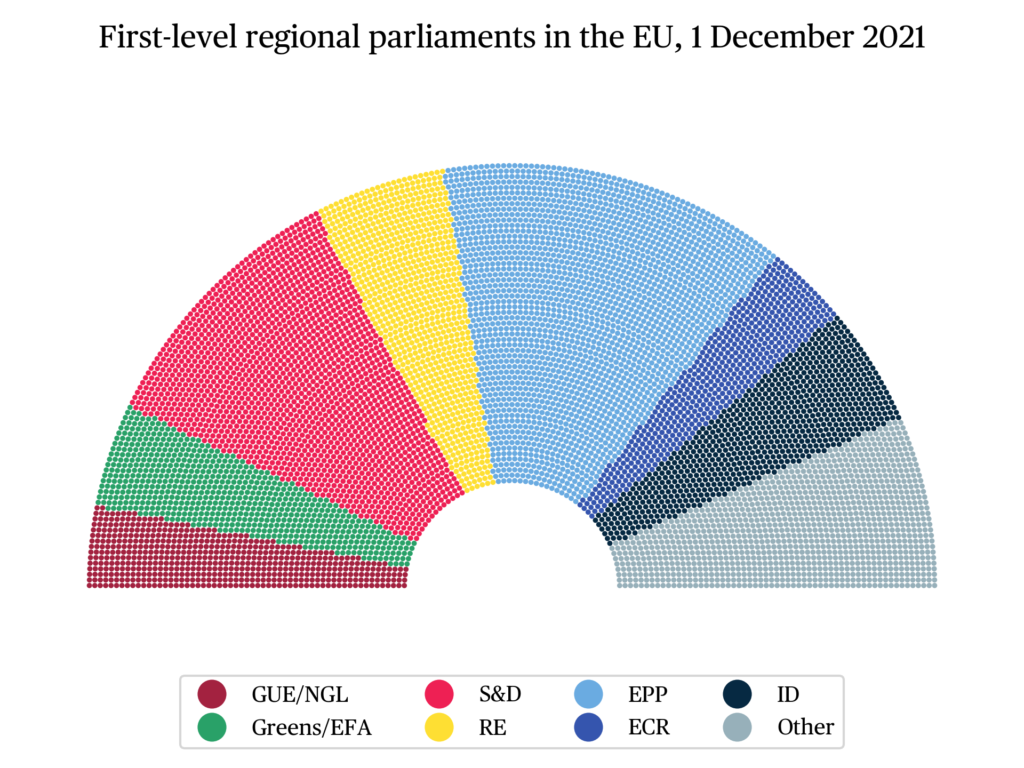

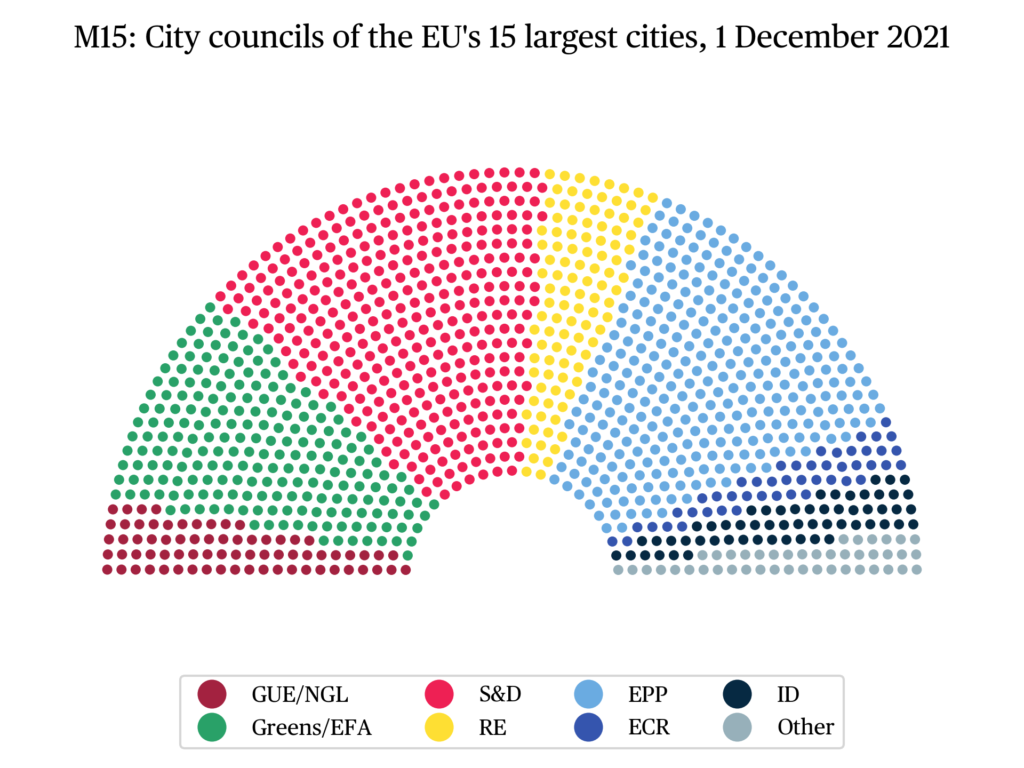

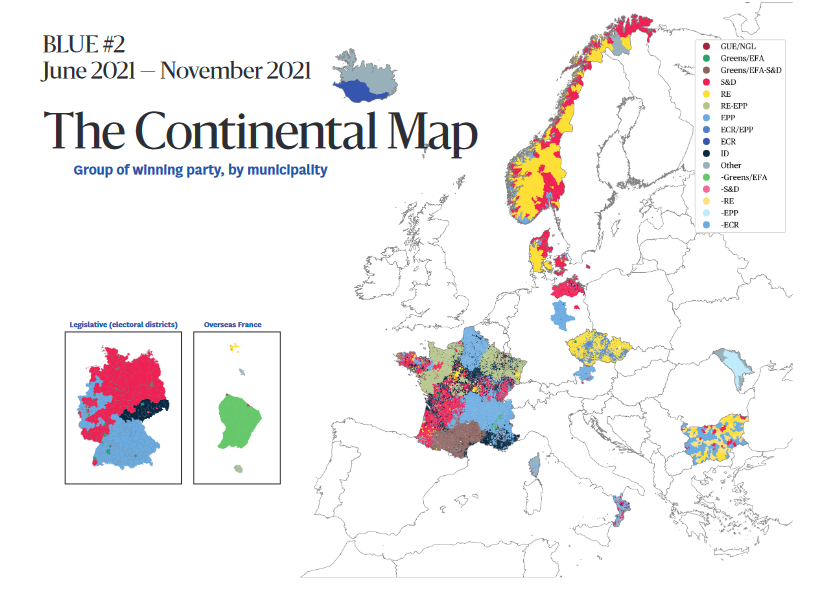

Seat shares of European political families, 1 December 2021

The European Parliament

The European Council

The Commission

Member states’ parliaments

Regional parliaments

City councils of the EU’s 15 cities with over one million inhabitants (“M15”)

The Continental Map

citer l'article

Théophile Rospars, Jean-Toussaint Battestini, Charlotte von Born-Fallois, Michał Ekiert, Juuso Järviniemi, Charlotte Kleine, The Continental Review, Mar 2022, 7-19.

à lire dans cette issue

voir toute la revue