The democratisation of EU nature governance: Making EU nature law more effective?

Suzanne Kingston

Professor, Sutherland School of Law, University College Dublin.Issue

Issue #3Auteurs

Suzanne Kingston

La Revue européenne du droit, December 2021, n°3

The groundwork of European power

Introduction

The EU 1 has some of the world’s most ambitious environmental laws on its books, but their effectiveness is seriously weakened by non-compliance in practice. Poor implementation is one of the major weaknesses of the EU’s environmental policy. 2

With the UNECE Aarhus Convention (1998), Europe launched an innovative legal experiment, democratising environmental enforcement by conferring citizens and environmental NGOs (ENGOs) with legal rights of access to environmental information, public participation, and access to justice in environmental matters.

At the same time, the European Commission has scaled back its own public enforcement efforts, citing its preference that Member State enforcers should take the lead, 3 and emphasising the important role of civil society as a “compliance watchdog” supporting the European Green Deal, the Von der Leyen Commission’s flagship initiative aiming to fundamentally transform the EU into a carbon-neutral economy by 2050. 4

Against the background of unprecedented environmental challenges, ongoing declines in biodiversity in Europe, 5 and the EU’s 2030 Biodiversity Strategy’s aim to improve implementation of the EU’s nature laws, there is an urgent need for policymakers to understand whether enabling private environmental governance through the Aarhus Convention is achieving its intended policy outcomes and, if not, the reasons for this. However, there has been surprisingly little systematic empirical research to date on how these innovative legal rights have been working in practice. 6

This paper summarises the results of a five-year empirical research project, which breaks new ground in mapping the evolution and effectiveness of the EU’s environmental governance laws. We examined the effectiveness of the EU’s nature governance laws in three Member States over a 23-year period from 1992, the date of adoption of the EU’s flagship nature law, the Habitats Directive. Using novel and complementary methodologies, including the coding of over 6,000 nature governance laws, over 2000 surveys and interviews across France, Ireland and the Netherlands, and a behavioural economics lab experiment, we show how nature governance laws have evolved over time, how they have been used in practice, how this has impacted landowners compliance decisions, and how it has impacted traditional public enforcement. 7 Our results point to practical ways in which nature governance laws might be made more effective. Beyond EU environmental law, they also demonstrate new empirical ways of measuring law’s impacts, which can be applied and adapted to other fields of regulation.

The role of the Aarhus Convention in bridging EU nature law’s implementation gap

The EU’s nature laws, notably the Habitats Directive (92/43/EC) and Birds Directive (2009/147/EC), provide for extensive protections including, in the Natura 2000 network, the largest coordinated network of protected sites in the world, covering over 18% of the EU’s terrestrial area and more than 8% of its sea area. 8 Buttressed by robust judgments from the CJEU, which interpret the requirements of the Habitats and Birds Directives strictly in light of the precautionary principle, protected habitats and species are subject to an impressively stringent legal regime on paper. 9 The practice, however, is often very different. The statistics are grim: in 2019, only 16% of protected habitats and 23% of protected species were in favourable conservation status. 10

The EU has embraced the private enforcement rights provided by the Aarhus Convention mechanisms as a means of combatting the serious problem of under-implementation of environmental law within Europe, including its nature laws. The aim of the Aarhus Convention is to increase citizens’ involvement in environmental matters, by creating the three so-called “pillars” of environmental governance rights: access to information, public participation and access to justice. In the case of access to information, these rights are to be granted to the public in general; in the case of public participation and access to justice, they are to be granted to the public “concerned” by the matter at issue (Articles 6(2) and 9(2)). Qualifying ENGOs are granted privileged status to enforce environmental law, being afforded legal standing to bring legal proceedings as of right (UNECE, 1998: Article 9(2). The State Parties are also obliged to ensure that legal proceedings falling within the scope of the Convention are not “prohibitively expensive” (Article 9(4)). Strengthening the Aarhus mechanisms forms an important aspect of the governance reforms proposed by the European Green Deal, as highlighted by the strengthening of the Aarhus Regulation in 2021, and the issuing of a (non-binding) 2020 communication on improving access to justice within Member States. 11 With this increasing reliance on the Aarhus mechanisms to bridge EU environmental law’s implementation gap, it is important to understand their effectiveness in practice.

Measuring the impacts of private nature governance: An interdisciplinary toolbox

In investigating this question, we employed an interdisciplinary toolbox, with three principal methodologies.

First, we engaged in qualitative research to explore how nature governance laws might best be designed to encourage voluntary pro-environmental behaviour. We conducted 2000 surveys and 165 in-depth semi-structured interviews across Ireland, France, and the Netherlands in 2018-2019, and spanning three important stakeholder groups in EU nature law governance: farmers and landowners within protected areas; ENGOs; and members of the public. These three States were selected to present a variety of geographic size of Member State, environmental conditions, and record of compliance with EU environmental law, legal “family” of the State at issue (common law or civil law), and length of time taken to ratify the Aarhus Convention.

Second, we engaged in quantitative statistical research, using leximetric coding of laws to map the evolution of nature governance laws at national, EU, and international levels, and their use in practice. We developed the Nature Governance Index (“NGI”), by coding over 6,000 nature governance laws, at international, EU, and national levels, from the birth of the EU’s flagship nature conservation law, the 1992 Habitats Directive (Directive 92/43/EEC) to 2015 inclusive. This provides the first systematic data showing the transformation of European nature governance regimes over time. We also developed the Nature Governance Effectiveness Indicators (“NGEIs”), a novel set of indicators measuring the impact of these new governance rights in practice since 1992. We regressed the NGEIs against the NGI to provide a first quantitative insight into whether these changes in nature governance laws have actually made a difference in practice, and their impacts on levels of traditional State enforcement. Data from the NGEIs were collected from a combination of publicly available information and over 300 formal and informal requests for access to environmental information made over a period of 3 years to the European Commission and to national and sub-national bodies within Ireland, France and the Netherlands.

Third, we designed a novel behavioural economics lab experiment, to test how nature governance rules affect compliance. We recruited 300 participants from students at University College Dublin to play a one-shot game that tested how traditional and private/Aarhus governance mechanisms made a difference to the behaviour of landowners and environmentally-motivated citizens in practice. Players took decisions and interacted with each other, by means of bespoke computer programme in a behavioural economics computer lab. The number of tokens (money) earned by each player at the end of the game depended on the decisions taken.

Results

Qualitative results

Outlining first the results of our qualitative research, our surveys and interviews revealed a rich tapestry of factors that either encourage (or magnetise), or discourage (or repel), pro-environmental action by landowners and potential private environmental enforcers. Table 1 summarises the factors that we found encourage, and discourage, voluntary private nature enforcement by citizens and ENGOs.

| Magnetising/encouraging factors | Repelling/discouraging factors | |

| Factors affecting ENGO enforcement | Belief that State is not doing enough (IE, NL) Need to counteract strong agricultural lobby (IE) Need to counteract underfunding of State nature conservation agency (IE) Belief in the transformative potential of EU nature conservation law (IE) Belief in the effectiveness of complaints from the ENGO sector (NL) Light-touch role of the European Commission (NL) | Lack of ENGO resources and expertise (IE, FR, NL) Unwillingness to act against farmers (IE, NL) Belief in State’s primary role as enforcer (FR) Exclusionary effect of requirement to have agrément (FR) ENGO resources used to support State enforcement (FR) |

| Factors affecting citizen enforcement | Would get involved if personally affected (IE, NL) ENGO support of citizen action (NL) | Lack of awareness of the mechanisms (IE, FR, NL) Belief in farmers’ autonomy over own land (IE, FR, NL) Cost and time (IE, NL) Social ostracisation (IE, NL) Complexity (FR, NL) The State should enforce; citizens’ role is to comply not to enforce (FR) Environmental activism is for ENGOs (IE, NL) Unwilling to restrict economic progress (NL) |

Table 2 summarises the factors that we found encourage, and discourage, farmers landowners’ voluntary pro-conservation activities.

| Factors magnetising/encouraging farmers’ voluntary pro-conservation activity | Belief in importance of nature in protected areas and farmers’ role as guardian of the land (IE, FR, NL) Involvement of local farmers in creating the specific rules to be applied and enforced (IE, FR, NL) Direct engagement with farmers in publicising the rules and the reasoning behind them (IE, FR, NL) Engagement with those ENGOS who have conservation expertise (IE, NL); communication and consensus-building (NL) |

| Factors repelling/discouraging farmers’ voluntary pro-conservation activity | Perceived procedural unfairness in Natura 2000 designations (IE) Perceived lack of publicisation of substantive Natura 2000 rules (IE, FR, NL) Perception that rules are imposed/policed by outsider State/ENGO city-dwellers who do not understand farming (IE, FR, NL) Perception that the rules do not make environmental sense (IE, FR) Inconsistencies between laws implementing Natura 2000 and agri-environmental subsidy schemes, and belief that agricultural schemes favour intensive farmers (IE) Disconnect between State’s environmental and agricultural bodies (IE) Involvement of ENGOs/citizens who have no connection with the local area (IE, FR, NL) Perception of certain ENGOs as serial objectors (IE) who vilify farmers (FR) and/or exaggerate (NL) Perception that ENGO/citizen may be using enforcement for their own selfish/NIMBY end (IE, FR) |

While there is a general consensus within ENGOs that the Aarhus mechanisms are helpful, relatively few ENGOs in Ireland and France actually made use of those mechanisms. Our in-depth interviews revealed varied reasons for this low take-up, in particular their limited resources and small number of staff members, the practical administrative and financial burdens entailed by using the Aarhus mechanisms, and (especially in the case of access to justice) the perception that use of this mechanism required special legal expertise.

In the case of members of the public, few had made use of their rights of access information or access to justice. However, the picture was different for public participation, as one quarter of citizens surveyed had previously exercised their right to make submissions.

Quantitative results

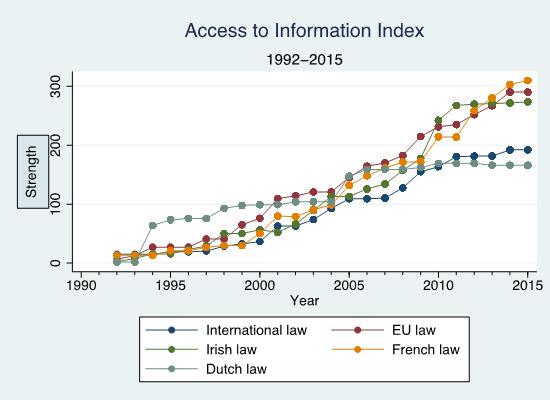

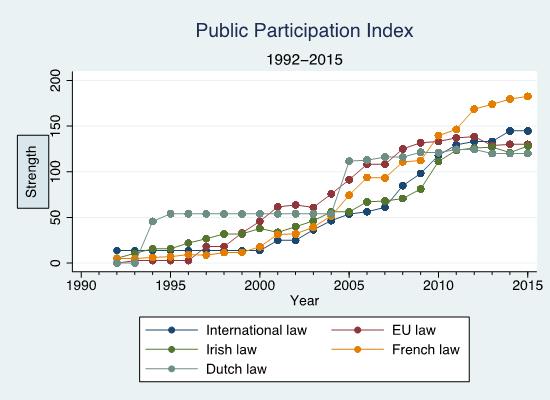

Turning to our quantitative research, in mapping the evolution of European nature governance laws 1992-2015, our results strongly confirm the democratic turn 12 in the evolution of European nature governance rules over the past generation.

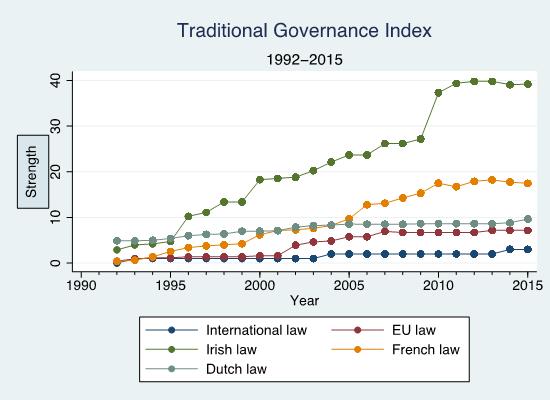

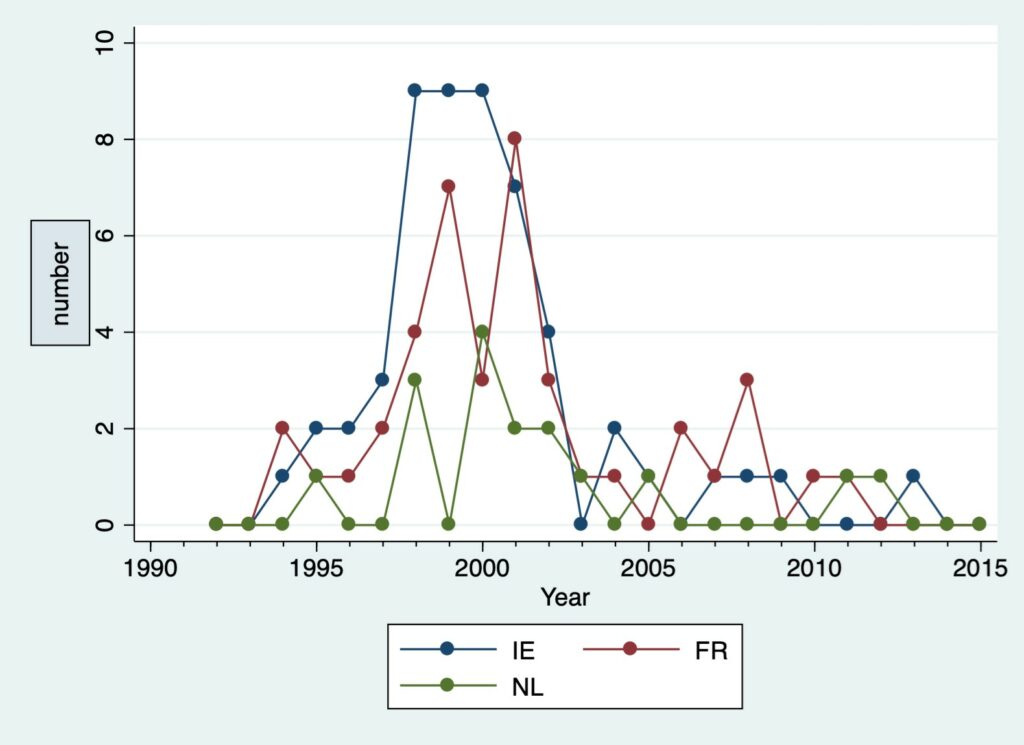

Figure 3: Trends in Traditional vs. Private Governance Compared.

As the extract from the Nature Governance Index in Figure 3 shows, the strength of traditional governance mechanisms (such as criminal penalties and civil fines) has remained relatively stable over the 23-year period.

In the Netherlands certain legislation (in particular the Flora & Fauna Act 1999, and the Nature Protection Act 1998) further strengthened the applicable traditional governance rules.

In the case of France, a gradual increase can be observed reflecting legislative strengthening, in particular through the establishment of sanctions for damage to preserved environmental areas (Law n° 95-101 relating to the strengthening of environmental protection) and to national and regional natural parks and marine natural parks (Law n° 2013-619 implementing certain EU law requirements in the field of sustainable development), along with the related case-law.

Conversely, Ireland stands out as a jurisdiction where the strength of traditional governance has increased markedly over this period. For Ireland, the next 23 years saw the passage of many important pieces of environmental legislation, including the Wildlife (Amendment) Act 2000 establishing national protected areas (National Heritage Areas), the Planning and Development Act 2000 which fundamentally reformed Irish planning and land use law, and the passage of a number of Ministerial Regulations transposing elements of the Birds and Habitats Directives.

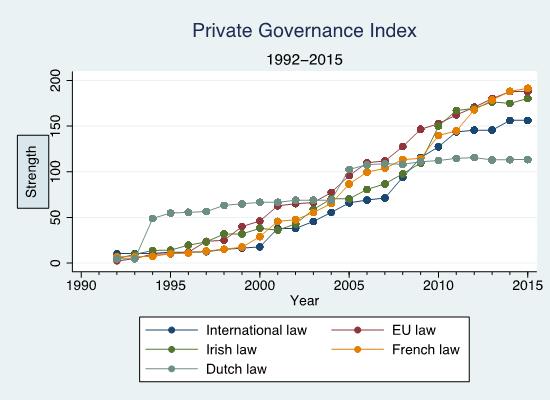

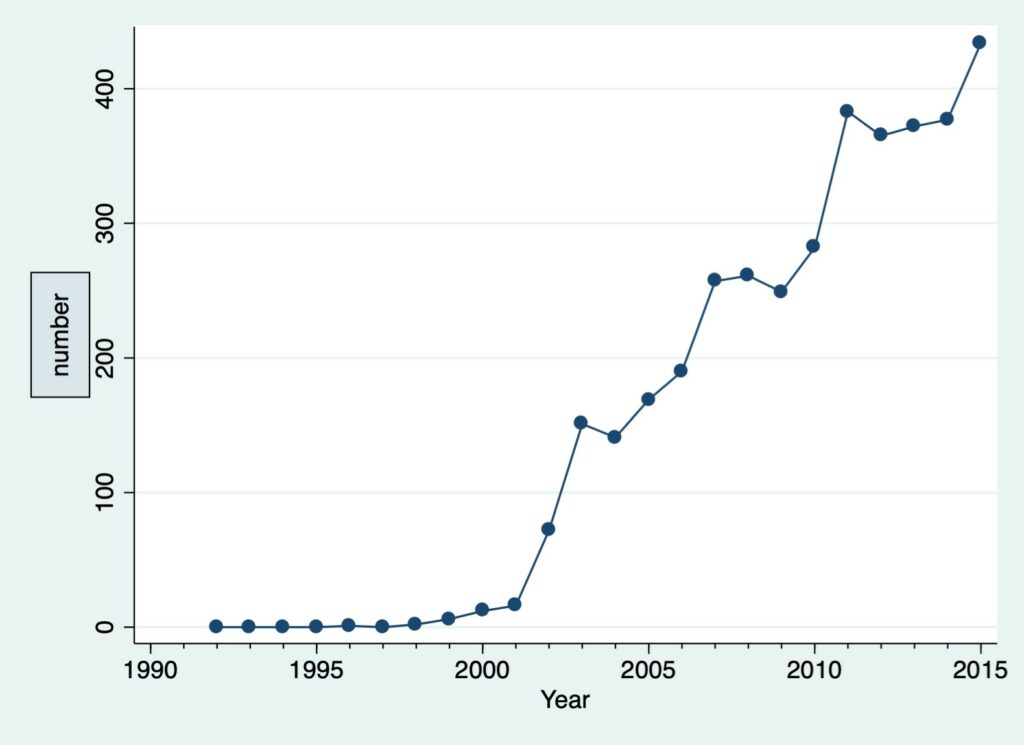

This relative stability of the studied traditional nature governance regimes from 1992-2015 stands in contrast to the marked increase in the strength of private / Aarhus governance mechanisms across Ireland, France and the Netherlands during this period.

The steady increase in the strength of private governance mechanisms under EU law reflects the EU’s decision to incorporate the Aarhus principles into EU law by means of the Access to Information Directive (Directive 2003/4/EC), the Public Participation Directive (2003/35/EC), the Decision concluding the Aarhus Convention on the part of the EU (Decision 2005/370/EC), and the Aarhus Regulation applying the Aarhus principles to the EU’s own institutions (Regulation 1367/2006).

French and Irish law followed broadly parallel trajectories to EU law, reflecting the fact that these States were not generally first-movers in incorporating private nature governance norms (i.e., the Aarhus mechanisms) within their governance laws, but rather did so after signature of the Convention.

The outlier trajectory is that of the Netherlands, where the strength of private nature governance rules increased and remained high even before signature of the Convention. This reflects the fact that the essence of the Aarhus mechanisms. i.e., access to environmental information, public participation and access to justice, were already to an extent present in Dutch law. For instance, the entry into force of the Environmental Protection Act in 1993, and the General Administrative Law Act 1994, inter alia codified ENGOs’ right of access to the courts. Indeed, our data reveal that private governance was, as a matter of law, already well-established in the Netherlands prior to Aarhus.

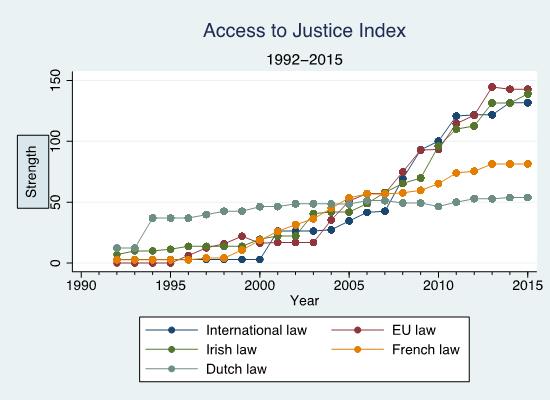

Our results also demonstrate the effects of lack of harmonisation 13 in the field of access to justice. Despite the efforts of the European Commission over some 20 years, Member States have resisted enshrining rights of access to environmental justice expressly in EU legislation, 14 leaving the Commission confined to publishing non-binding guidance on the matter 15 save in certain limited fields such as environmental impact assessment and industrial emissions.

Figure 4: Trends in Access to Information, Public Participation and Access to Justice Compared.

Our results confirm that, in the European Commission’s continued quest to strengthen access to environmental justice within Member States, express legislation remains the “holy grail”. This is, indeed, consistent with the European Commission’s recent express plea to the EU co-legislators (i.e., the Council and the European Parliament) to include express access to justice provisions in binding new or revised EU environmental laws. 16

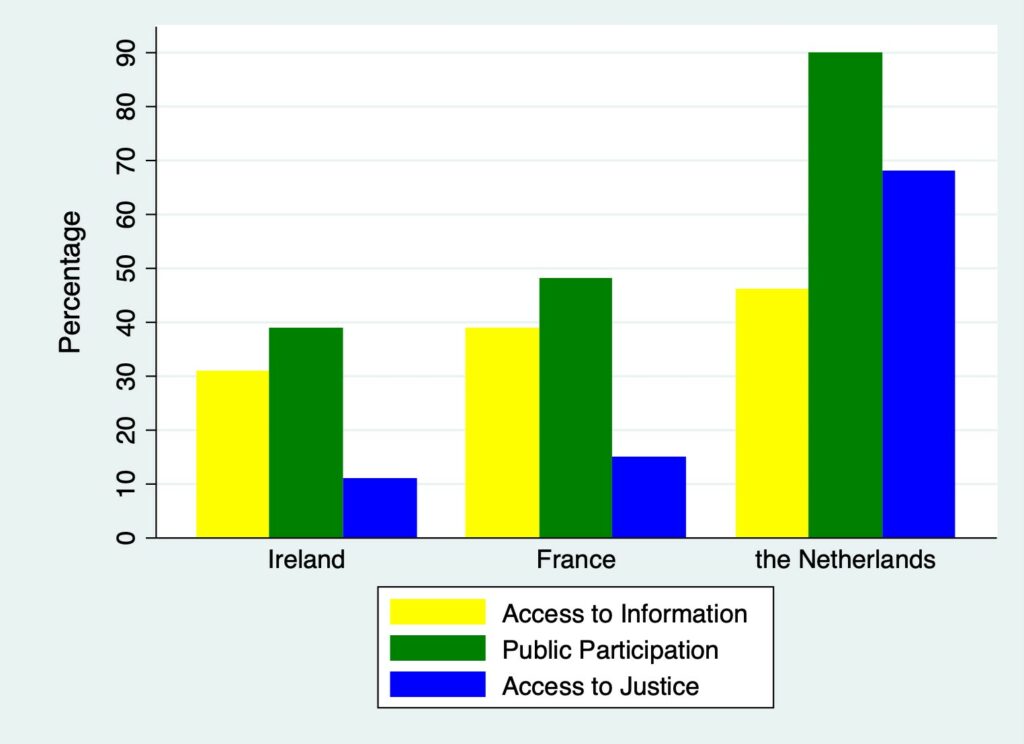

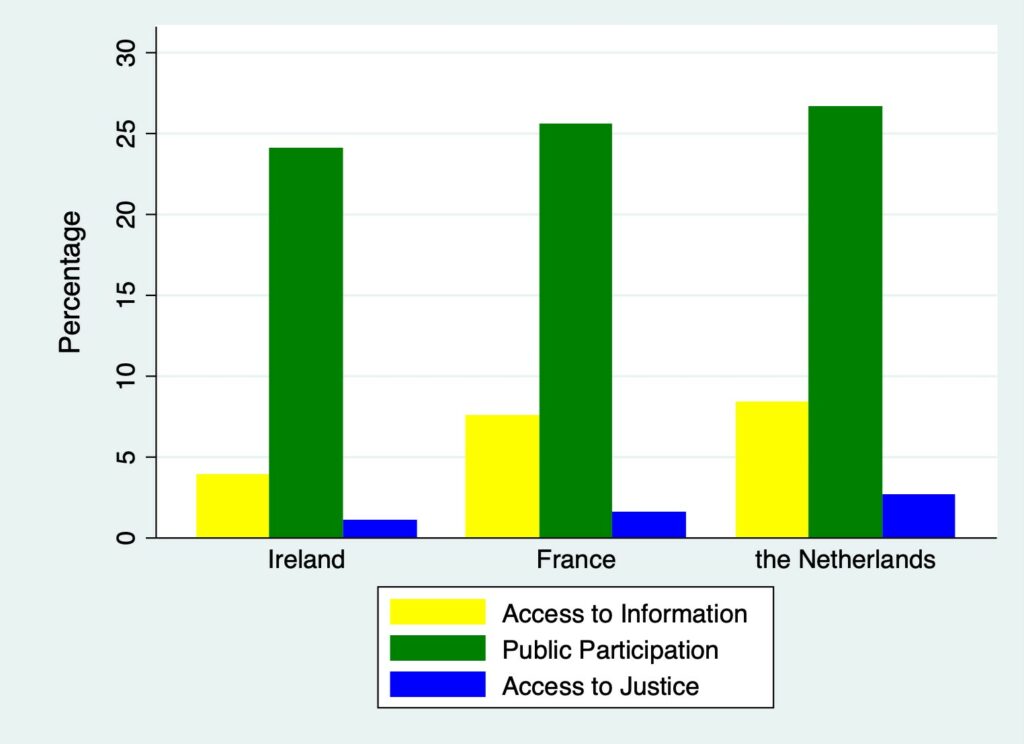

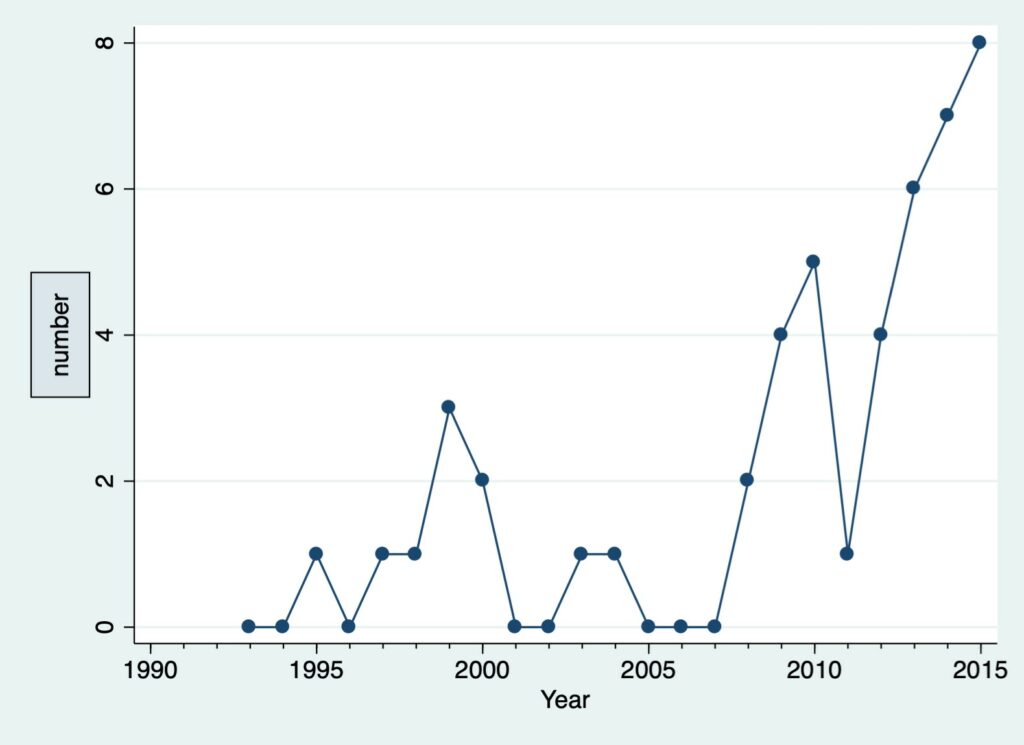

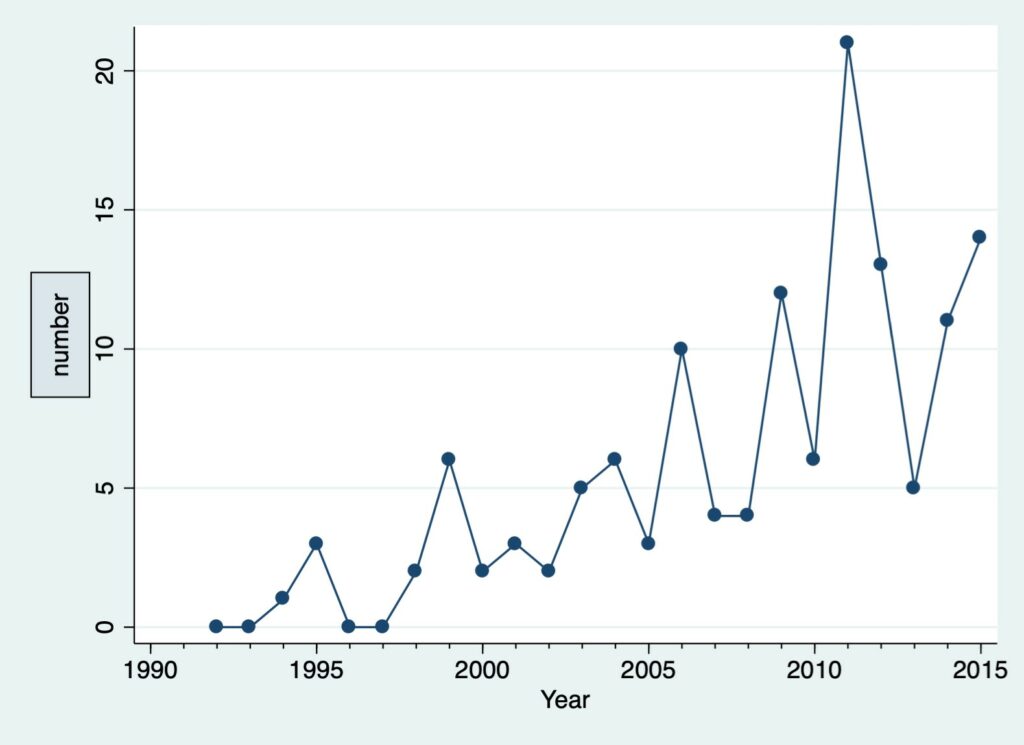

Turning then to our results from the Nature Governance Effectiveness Indicators, our results tell a cautionary tale of Europe’s private nature governance revolution. While our results confirm the widespread embrace of private nature governance laws on the books across our studied jurisdictions from 1992-2015, they also provide, to our knowledge, the first systematic empirical evidence that these enhanced rights for citizens are not being consistently used in practice. To take access to justice as an example, while we certainly found an increase in cases brought by private parties to enforce EU nature law before national courts, this increase was bumpy and, in the case of Ireland and France, figures still remained at relatively low levels (Figures 5A and 5B). Overall, the use of private nature governance mechanisms in practice has not kept pace with their development in law. Further, data on levels of use of the Aarhus mechanisms were often difficult to access, leading to a basic lack of transparency on the success of these new governance mechanisms, a situation itself incongruous with the aims of the Aarhus Convention.

Figure 5: Number of proceedings brought by private parties (including ENGOs) before national courts where the Plaintiff sought to enforce EU nature law, 1992-2015

With respect to enforcement proceedings by the European Commission, our data show a clear peak in the commencement of Article 258 TFEU proceedings against all three Member States between the years 1997 and 2003. Such proceedings start from a low level prior to 1997 and revert back to a low level from 2003 onwards (Figure 6). These data support the view that the Commission has moved towards a “management” approach to environmental compliance, even within the field of nature law, reducing its use of formal legal proceedings.

Our statistical regression results also reveal for the first time that, despite these inconsistencies in usage of the Aarhus mechanisms in practice, passing private governance laws can in fact improve levels of State enforcement of EU nature law in practice. Fascinatingly, we found that, while strengthening private governance laws significantly improved levels of State nature enforcement, strengthening traditional governance laws did not. This suggests that, by strengthening Aarhus/private governance rules, States can harness a shadow of heterarchy to increase the strength of State enforcement of EU nature law on the ground. 18

Experimental behavioural economics results

Our lab experiment confirmed that traditional and private environmental governance rules together achieve more effective nature conservation outcomes than traditional governance rules alone. This provides empirical support for the common assumption that strengthening mechanisms of “environmental democracy”, and the Aarhus mechanisms in particular, leads to improved environmental outcomes.

Our experimental results also show that there is far less need for environmental governance rules of any sort – whether traditional or private/Aarhus governance rules – if landowners hold strong intrinsic pro-environmental values. This suggests that enforcement resources might best be directed to those with weaker intrinsic environmental values, and complements qualitative research showing that reliance on traditional or private governance rules in cases of strong intrinsic pro-environmental motivations on the part of landowners can be counterproductive.

Further, our experimental results show that perceptions of the effectiveness of traditional environmental enforcement does not deter citizen enforcers (i.e., the “public”/the “public concerned” within the meaning of the Aarhus Convention). These results therefore question the typical narrative on the part of public enforcers, such as the European Commission, that the Aarhus mechanisms are destined to fill the implementation gap left by public enforcement. However, we note that our experiment did not capture the case of ENGO enforcers, who may be in a position to act more strategically than individual citizen enforcers in choosing to be active where public enforcement is lacking.

Conclusion

Improving enforcement of the EU’s nature laws is at the heart of the EU’s 2030 Biodiversity Strategy, and is acknowledged by the European Commission as essential in dealing with Europe’s biodiversity crisis (European Commission, 2020a). The Aarhus Convention, and its empowering of private governance by enabling civil society enforcement through law, has been a cornerstone of Europe’s environmental enforcement strategy for the past generation.

Our results reveal that, contrary to what might be assumed, Europe’s private governance revolution has not been at the expense of traditional governance techniques, such as strengthening of criminal sanctions and civil/administrative fines. Rather, private governance has evolved alongside traditional mechanisms, especially at the national level.

Our findings further show striking differences between States’ approaches to nature governance and the impact of EU law in this field, ranging from first-mover (the Netherlands), reactive (Ireland), or something in between (France). Ultimately, they strongly confirm that, even when Member States are independently bound by the Convention as a matter of international law, important divergences between national governance laws will remain, absent express harmonisation in EU law.

In addition, even where legal rights of private enforcement are provided for in law, an unsupportive regulatory culture can subvert private enforcement initiatives. The formal hierarchy of law is not enough. For private environmental enforcement to flourish in practice, this requires a supportive regulatory culture, fostered by the State. The use of the Aarhus mechanisms must be straightforward, uncomplicated, and cheap. From the EU perspective, if the Commission wishes to increase private enforcement activity, it must therefore go beyond monitoring formal implementation of the Aarhus requirements to ensure that the State fosters a regulatory culture that is supportive of and open to private enforcement. Ultimately, despite all the EU’s emphasis on the Convention, there remains a strong belief (across all three jurisdictions, and all three stakeholder groups) in the central role of public enforcement by the State and/or the European Commission.

Moreover, our findings show that, contrary to the typical narrative that private enforcement enables “environmental democracy”, in fact the Aarhus mechanisms are largely being used by a sub-group of specialised ENGOs, not citizens in general. Breaking that mould will, our evidence suggests, require more than the passage of new laws, or even State resources and clear publicisation of the rights at issue, but will require a deeper shift in regulatory tradition and culture, which we doubt can be achieved by the State alone. Furthermore, if the policy aim is truly that of enhancing environmental democracy, there are perhaps more directly effective tools than the Convention. One such tool might be, for instance, a consultative and deliberative citizens’ forum encompassing environmental governance, including nature governance, and which could embrace other stakeholders, including the State, ENGOs and farmers. This could draw from citizen deliberative models such as the Constitutional Convention and Citizens Assembly on Climate Change in Ireland.

In sum, our results point to four principal policy lessons. First, in making nature laws more effective, knowledge, communication, and clarity matter. Not just of the content of the law but also its environmental purpose. Across each jurisdiction, our data suggest a need for a clear and independent source of information for landowners, citizens and ENGOs on the purpose and content of the EU nature rules and the Aarhus mechanisms.

Second, procedures, consultation and inclusivity also matter. We found evidence in each State that, in protected areas, locally-led conservation farming schemes that have regard to the specific nature of the protected habitats or species at issue, and involve farmers, can strongly encourage pro-environmental motivations of participating farmers.

Third, efforts to increase levels of private nature governance have not entirely succeeded to date. Member States, and the European Commission, should be cautious in relying on private nature enforcers as (part of) the solution to the EU’s nature law implementation gap. Our quantitative results underscore the danger in overreliance on the Aarhus mechanisms to fill the gaps left by under-enforcement by State and/or EU authorities. Specifically, they highlight the fact that passing private nature governance laws is far from the end of the story for policymakers wishing to engage a potential citizen “watchdog” environmental enforcement army to complement public enforcement. There are still major gaps in their effectiveness in practice, and significant divergences between Member States in the extent to which private citizens and ENGOs engage.

Finally, strengthening private nature governance may have the added benefit of improving levels of State enforcement in practice. We found that, while strengthening private governance laws significantly improved levels of State nature enforcement, strengthening traditional governance laws did not. For policymakers seeking to increase enforcement of EU nature law on the ground, strengthening private governance rights may therefore be a more effective means of doing so than simply ratcheting up existing traditional governance mechanisms such as levels of maximum criminal penalties or civil fines.

Notes

- This work was funded by the European Research Council (ERC) under the European Union’s Horizon 2020 research and innovation programme (grant agreement No 639084). Further details on the project and its scientific publications can be found at https://effectivenaturelaws.ucd.ie/. Special thanks go to Dr. Zizhen Wang, Edwin Alblas, Dr. Mícheál Callaghan, Julie Foulon, Clodagh Daly, Deirdre Norris, Dr. Valesca Lima, and Dr. Geraldine Murphy, members of the Effective Nature Laws research team.

- “Implementation” here is used in the general sense to extend not only to formal implementation by means of legal norms transposing, for instance, a Directive, but also practical implementation and enforcement, as employed in the key recent policy documents in the field, including the European Commission’s Communication on the Environmental Implementation Review, Delivering the benefits of EU environmental policies through a regular Environmental Implementation Review COM(2016)316 final, and the European Commission’s Communication on the EU Biodiversity Strategy for 2030, Bringing Nature Back Into Our Lives, COM(2020) 380. The Environmental Implementation Review, for instance, discusses the “implementation gap” within EU environmental law as denoting the regulatory and enforcement gaps leading to situations in which EU environmental legislation fails to achieve its goals in practice, and is ineffective in achieving these goals.

- Hofmann A (2018) Is the Commission levelling the playing field? Rights enforcement in the European Union, Journal of European Integr

- European Commission (2020) Communication on the EU Biodiversity Strategy for 2030, Bringing Nature Back Into Our Lives, COM(2020) 380; European Commission (2020) Communication on Improving access to justice in environmental matters in the EU and its Member States, COM(2020) 643.

- European Commission (2020) Communication on the EU Biodiversity Strategy for 2030, Bringing Nature Back Into Our Lives, COM(2020) 380.

- For important work in the field, see, e.g., Eliantonio, M. (2018) The role of NGOs in environmental implementation conflicts: ‘stuck in the middle’ between infringement proceedings and preliminary rulings? Journal of European Integration, 40:6, 753-767, and Darpö, J. (2013). Synthesis report of the study on the Implementation of Articles 9.3 and 9.4 of the Aarhus Convention in the Member States of the European Union. Available at https://ec.europa.eu/environment/aarhus/ (accessed 12 November 2021).

- The principal findings of the project, outlined in this paper, are further detailed in Kingston, S., Alblas, E., Callaghan, M. and Foulon, J. (2021b), Magnetic law: Designing environmental enforcement laws to encourage us to go further. Regulation & Governance. https://doi.org/10.1111/rego.12416; Kingston, S., Wang, Z., Alblas, E. et al., The democratisation of European nature governance 1992–2015: introducing the comparative nature governance index. Int Environ Agreements (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10784-021-09552-5; Kingston, S., Wang, Z., Alblas, E., Callaghan, M., Foulon, J., Daly, C., and Norris, D., Europe’s Private Nature Governance Revolution: Harnessing the Shadow of Heterarchy (forthcoming); and Kingston, S., Wang, Z., How do Nature Governance Rules affect Compliance Decisions? An Experimental Analysis (forthcoming).

- European Commission (2020) Communication on the EU Biodiversity Strategy for 2030, Bringing Nature Back Into Our Lives, COM(2020) 380.

- See generally, Kingston, S., Heyvaert, V. and Čavoški, A. (2017). European Environmental Law. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, ch. 12, and, e.g., Case C-127/02 Waddenzee and Case C-243/15 LZ (No. 2)(“Brown Bears II”).

- European Environment Agency (2019), The European Environment – state and outlook 2020. Luxembourg: Publications Office of the European Union.

- European Commission Communication on the EU Biodiversity Strategy for 2030, Bringing Nature Back Into Our Lives, COM(2020) 380; European Commission Communication on Improving access to justice in environmental matters in the EU and its Member States, COM(2020) 643; European Commission “Political agreement on the Aarhus Regulation: Commission welcomes increased public secrutiny of EU acts related to the environment”. Press Release of 13 July 2021, IP/21/3610.

- In the sense, as noted in the Introduction, of the democratization of environmental enforcement by conferring citizens and ENGOs with legal rights of access to environmental information, public participation, and access to justice in environmental matters.

- I.e., the passage of express EU legislation concerning access to justice in environmental matters.

- Kingston, S., Heyvaert, V. and Čavoški, A. (2017). European Environmental Law. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, ch. 7, pp. 237-246. The Commission proposed a general Directive on access to justice in environmental matters in 2003 (COM(2003)624), but this met with opposition in the Council. The most recent Commission Communication on improving access to justice in environmental matters (COM(2020)643) continues to emphasise the need for greater legislative harmonisation in this field, as discussed below.

- European Commission. Communication by the Commission: Commission Notice on Access to Justice in Environmental Matters, C(2017) 2616; European Commission, Communication on Improving access to justice in environmental matters in the EU and its Member States, COM(2020) 643.

- Ibid.

- Source: Data obtained from European Commission, DG Environment.

- By contrast to the shadow of hierarchy that has been shown to exist as a result of hierarchical legal architectures in certain cases: see, e.g., Borzel, T., 2010. “European Governance: Negotiation and Competition in the Shadow of Hierarchy” 48(2) Journal of Common Market Studies pp.191 – 219.

citer l'article

Suzanne Kingston, The democratisation of EU nature governance: Making EU nature law more effective?, Dec 2021,

à lire dans cette issue

voir toute la revue