What can the European political community achieve?

Daniela Schwarzer

Executive Director, Open Society Foundation Télécharger le pdf

05/10/2022

What can the European political community achieve?

Daniela Schwarzer

Executive Director, Open Society Foundation

05/10/2022

Voir tous les articles

Voir tous les articles

What can the European political community achieve?

Ahead of the first meeting of the European Political Community on October 6, 2022, the debate about the potential and the risks of this new attempt to organize relationships between countries and the EU on a continental scale is in full swing.

Recognizing geopolitical shifts on our continent and worldwide, leaders can seize the opportunity to build a new forum for strategic exchange and policy-making on a pan-continental scale. For it to be effective, however, the terms of reference for future meetings need to be clearly defined and the upcoming meeting should be an ambitious start of this conversation. After this first meeting, governments will closely analyze whether there is an added value in being part of it. A prerequisite will be that they see a benefit in the joint work and in concrete policy progress and consider themselves at eye level in this comparatively large group.

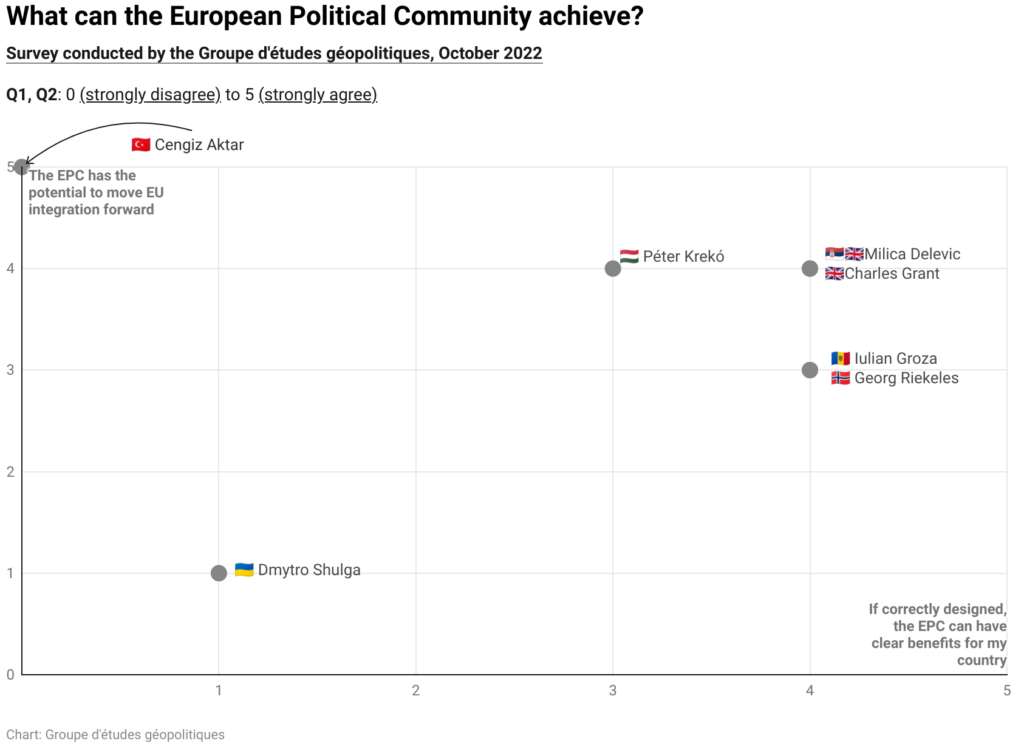

Following the publication of our policy contribution «Enlarging and deepening: giving substance to the European Political Community», we have asked seven contributors to rank on a scale from 0 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree) two statements :

- The EPC has the potential to move EU integration forward ;

- If correctly designed, the EPC can have clear benefits for my country.

The results of this survey offers a great opportunity to share ideas and assess perspectives on the EPC from outside the European Union. Several common themes emerge that should be part of the debate among the 40+ leaders on Thursday. One concerns the terms of reference – it will be key to see whether leaders can agree on a common base of values and principles. Contributors also mention the necessity of geopolitical alignment between countries. If leaders decide for ambition and clarity, it may put some governments which do not abide by EU or Council of Europe norms to the difficult decision whether the change policy – or opt out of the EPC.

Another topic raised is the benefit of being part of the EPC and what this means for membership perspectives for those countries that seek accession: Expectations are very clear that EPC should not replace accession, but should be a bridge that it actually supports and accelerates integration.

There are also a number of interesting ideas which policy areas should take priority for this new forum given the challenges the European continent is facing. An important topic that clearly requires further debate is the question of institutionalisation, legal base and in particular the role of EU institutions. Close proximity to the European Union is seen as an advantage by some and as a reason not to join by others.

We invite you to read the expert views below which include important design suggestions and share interesting insight into diverging national perspectives at an early stage of shaping a new continental partnership.

0 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree)

1. The EPC has the potential to move EU integration forward.

2. If correctly designed, the EPC can have clear benefits for my country

Dmytro Shulga (Ukraine)

European Programme Director, the International Renaissance Foundation

(Q1) 1/5

(Q2) 1/5

The idea behind EPC is to offer some engagement to non-EU countries while keeping enlargement on hold. This will not satisfy Ukraine or Montenegro, and will hardly provide added value for the UK or Switzerland who seek less influence from the EU institutions, not more. Decision-making in an inclusive, diverse group may be problematic, with unclear implications for mandate sharing with EU institutions.

From a Ukrainian perspective, most problematic is the premise that EU enlargement is a decades-long process, which can move forward only after internal EU institutional reform. Relevant statements by Macron and Scholz were supported in the text published by le Grand Continent, by Daniela Schwarzer, Jean Pisani-Ferry et al. – but can be challenged.

On the question of veto in the European Council, Ukraine can commit to not use veto right on its own, i.e. to not behave like Hungary. The European Parliament is, according to Chancellor Scholz and the authors of the paper, ‘bloated’ – however, it has fewer members than the Bundestag. Recently, the number of MEPs has actually decreased following Brexit. If Ukraine and other candidates join, it will not ‘bloat’ the Parliament, as the number of MEPs would increase according to the size of the population – the population of the UK is equivalent to that of all the Western Balkans, Ukraine, Moldova, and Georgia combined. The only problematic institutional issue might be the fragmentation of the European Commission, where, according to current Treaties, all members delegate a commissioner. This may be solved by a creative administrative solution. This is not a sufficient problem to legitimize blocking Ukraine’s progress towards EU accession.

Enlargement should not be frozen until 2030, as suggested by Daniela Schwarzer, Jean Pisani-Ferry et al. Accession talks with Ukraine can happen in parallel with EU internal reform (which is indeed necessary), and should not take decades but a couple of years, as was the case in all previous successful EU enlargements.

Iulian Groza (Moldova)

Executive Director of the Institute for European Policies and Reforms (IPRE, Chișinău) and former deputy minister of Foreign Affairs and European Integration of the Republic of Moldova

(Q1) 3/5

(Q2) 4/5

The European Political Community goes back to the roots of the “Wider Europe” concept. Forty-four European countries are invited to the first EPC Summit in Prague. The majority of these states have various degrees of integration and cohesion with the EU, namely the EU membership applicants (the Western Balkans, Moldova, Ukraine, Georgia, and Turkey), EFTA states, and the UK. The exception is Armenia and Azerbaijan, having a lower degree of integration with the EU. While welcoming the inclusive approach, it is also important for the EPC to not just be another forum of discussion and become yet another platform for political exchanges. The EPC should not become a framework that could repeat the experience or duplicate existing formats such as the Council of Europe or OSCE. European democracies and democratic values should be indeed at the heart of the EPC. Thus, EPC should develop a cooperative relationship with the Council of Europe on matters related to democracy, rule of law, and human rights. On the other hand, the EPC should provide for a venue to address collective security and stability that OSCE cannot currently tackle, being paralyzed by Russia.

EPC should not be an alternative to EU enlargement but rather help to revive the European project based on common values and joint interests to ensure security and prosperity on the European continent. It should help the transition of Moldova, Ukraine, and Georgia, when ready, from the EU’s neighborhood Eastern Partnership towards the revised enlargement policy. EU accession is a long process. However, the 2014 Association Agreement with the EU, along with Moldova’s participation since the early 2000’s in Southeast European formats (SEECP, RCC, CEFTA), lays already solid grounds in terms of association and the economic integration process with the EU. Thus, EPC should provide for a reinforced platform to assist Moldova, Ukraine, and Georgia on their membership path, enact democratic and economic reforms, and to reach intermediate integration milestones, such as accession to EU’s single market. EPC should help Moldova to increase its democratic, economic, and security resilience, support sustainable development, and accelerate accession to the EU.

Milica Delevic (Serbia, UK)

Director for Governance and Political Affairs, European Bank for Reconstruction and Development

(Q1) 4/5

(Q2) 4/5

In this era of strategic challenges ranging from geopolitics to climate, energy and economy, an inclusive forum ensuring regular multilateral and bilateral dialogue among European leaders is undoubtedly a good thing.

It will bring together representatives of most of the continent’s countries and as such will go well beyond the EU’s borders. While the author of the initiative, the French President Emmanuel Macron, has said that he wants to avoid a central role of EU institutions, the fact is that all of the countries invited already have contractual relations with the EU. These are, however, very diverse — from members to applicants, candidates, more or less closely associated partners, to a disgruntled former member. This diversity gives the exercise an added value as it allows for engaging in a manner going beyond the set templates on which the EU normally relies with each of these groups. However, it also poses a challenge as attempts at more substantial collaboration could be perceived as replacing or duplicating existing sets of relationships, most notably enlargement.

To avoid merely talking shop, the EPC should, on the one hand, build on the diversity of relationships between participating countries and the EU, and on the other, avoid hollowing out existing processes. This could be done by using the exercise as an impetus for opening up sectoral integration to more European countries. The model could be the Schengen zone of passport-free travel, in which a number of non-EU countries participate, whereas some EU countries do not. This would allow the necessary involvement of EU institutions instead of inter-govermentalising processes normally run by them. Most importantly, by promoting sectoral integration in line with the concept of variable geometry, the EPC could help bring the continent closer together in a way that is both inclusive and flexible.

Péter Krekó (Hungary)

Executive director, Political Capital

(Q1) 4/5

(Q2) 3/5

Not only has NATO received new momentum after Russia brutally invaded Ukraine, but the EU has as well. Russia successfully improved the attractivity of democratic and defence cooperation by showing a not-so-attractive alternative. And while the candidate status that the European Union gave to Ukraine and Moldova was a historic and important move at the right moment, it caused some negative sentiments toward other hopeful EU-member states in the Western Balkans. Some think that while these two countries deserve these gestures from the West, the decision circumvented the protocols of the accession process, and these countries received candidate status less for their achievements in democratization and institution-building, and more due to the geopolitical environment.

Furthermore, we can again see that ethnic tensions are rising in the Western Balkans. The North Kosovo crisis, the increasing secessionist tendencies of Republika Srpska, protests in North Macedonia and Serbia all reflect growing antagonism not only between certain ethnic groups and countries, but towards some Western institutions (e.g the High Commissioner) as well. Russia has been quite active in helping to fuel these tensions by supporting Serb nationalism, secessionism, and trying to hamper the peaceful solutions of ethnic and bilateral conflicts. And even if Russia — who is focusing on keeping its hold on Eastern Ukraine — currently has less capacity to act as a spoiler in the region, the tensions are so high that a spark could be sufficient to trigger an explosion. We can see at the same time that not all the problems can be targeted by the EU. The Commissioner for Enlargement has been blamed for being partial in come conflicts, and the willingness of some EU Member States – such as Hungary – to find constructive solutions to existing problems is questionable, to say the very least. Some EU member states, such as Bulgaria and Croatia, are active participants in some bilateral conflicts (with North Macedonia and Serbia), which further weakens the EU’ s role as an impartial external actor.

In this situation, the European Political Community (EPC), if it operates efficiently, can have a virtuous role in keeping up the dialogue, targeting serious questions that the EU cannot, and trying to keep up euro-optimism and fight against accession fatigue.

But it is also very important, as Piotr Buras has argued, that at the same time, the accession process moves further – otherwise hopeful EU members may feel that they are deceived by nice, but meaningless gestures. How can this be achieved? Franz C. Mayer, Jean Pisani-Ferry, Daniela Schwarzer, and Shahin Vallée are coming up with very specific proposals on how to make this initiative meaningful and substantial – such as, for example, operating as a “soft law agreement” between candidate countries and the EU, and working with existing institutions while avoiding their shortcomings. For example, the EPC can operate without vetoes, which have been paralyzing EU decision-making for some time, and have long given an opportunity for foreign authoritarian actors to undermine foreign policy decisions by member states from within.

Georg Riekeles (Norway)

Associate Director, European Policy Centre

(Q1) 3/5

(Q2) 4/5

When, where, and how often do Erdoğan, Macron, Scholz, Truss, and von der Leyen meet? That is a fundamental question as war has once again taken hold of Europe. The calls for immediate institutionalisation and the possible mix-up with EU enlargement should be resisted. For now, the European Political Community is the artifice to make sure that European leaders sit down together around a table. Wartime demands a new form of informal, continental, cross-organisation dialogue on the most pressing questions: upholding a common front against Putin’s Russia, boosting support for Ukraine and sanctions, avoiding energy nationalism this winter, coordinating messaging to China and India, and, distressingly, building an understanding of threats and responses should escalation strike.

From being a peripheral country, often minding its own business, Norway has discovered it is being called upon to play an active role. Oslo is therefore clearly welcoming the European Political Community initiative. As a rich energy producer, Norway’s reputation is at stake after strong reactions from a crisis-stricken Europe. In Prague, Prime Minister Støre should prioritize explaining what (more) Norway can do for Europe’s energy security and lower gas prices. More fundamentally, despite having rejected EU membership in two referendums, Oslo does consider it a challenge to watch EU institutions and leaders’ meetings from the sidelines. Had the UK not beaten us to it, Norway would therefore have wanted to host the next European Political Community summit after Prague.

This said, the future demands on the European Political Community are of a different order. Addressing Europe’s long-term, common challenges in security and defence, energy and climate, and digital and economic security will require considerable means and the kind of institutional underpinning that only the EU can currently deliver. In this regard, it would eventually make sense for the European Political Community’s summits to be held back-to-back with European Councils, two or three times per year, thus fulfilling Norway’s long standing aspiration for closer involvement, but also more fundamentally, as part of the structuring of a geopolitical Union.

Cengiz Aktar (Turkey)

Turkish political scientist, essayist and columnist

(Q1) 5/5

(Q2) 0/5

I strongly agree with the proposal. Since its inception, an executive and supra-national Europe was considered the most suitable response to the post WWII challenges on the continent, in particular in connection with the vicinity of a vast, non-democratic, and hostile polity, i.e. the USSR. The US was a staunch supporter of that Europe. Today, after more than sixty years and in view of a materialized threat with the invasion of Ukraine, the EPC appears more urgent than ever. Paradoxically though this dynamic is emerging from the ex-Warsaw and ex-Soviet bloc members of the EU, thereby shifting its center of gravity to the continent’s east.

The EPC could, by definition, be beneficial to the entirety of EU polity as well as the candidate countries by setting and raising standards and pulling the laggards up. Nevertheless, Turkey looks to be at odds with such a dynamic. Neither the present regime nor its challengers have any credible European vision or perspective, perhaps including even the most liberal segments of the political microcosm, the HDP. As for society, the EU perspective has no concrete meaning but to represent an escape route from the totalitarian practices of the Erdoğan regime. We should bear in mind that Turkey has been rapidly de-westernizing in the last ten years, reversing the two-century old western drive. As for Europeans, Turkey is no longer on their political radar and doesn’t seem that it will be back anytime soon. In other words, the EPC or any other strong integration architecture has to actually exist and thrive against the two totalitarian eastern neighbors, Russia and Turkey, in the decades to come.

Charles Grant (UK)

Director, Centre for European Reform

(Q1) 4/5

(Q2) 4/5

Emmanuel Macron’s proposal for a European Political Community is good for European integration though not necessarily EU integration per se. Given the challenges posed by Russia’s invasion of Ukraine and the consequent threats to energy security, Europe needs a forum where all the European countries that are more-or-less democratic can exchange views. The wider Europe will carry more clout than the EU on its own. The EPC will succeed if it fosters some geopolitical alignment among its members.

There are, broadly, two schemes for how the EPC could work. First, a communautaire model, in which the EU dominates, the Commission runs the show and accession countries gain some benefits of membership before they join. Second, an inter-governmental model, similar to that of the G-20, in which the EU stays in the background and there is little in the way of institutional structure. This would make it harder for the EPC to focus on economic as opposed to strategic issues.

The proposal of Daniela Schwarzer, Jean Pisani-Ferry and others follows the first model: there would be a large budget and qualified majority voting for decision-making, while the Commission would run the secretariat and a treaty would define relations between the EU and non-EU participants. This proposal is intellectually coherent, but if implemented would guarantee the non-participation of the UK and several other non-EU countries. The British have decided to leave the EU and its voting rules, treaties and budgets, and would view the EPC as a means of pushing them back in via the back door. And if the EU dominated the forum, a country like the UK, being smaller and weaker than the EU, would fear being treated as a second-class member. To their credit, Macron and other EU leaders seem to have got the point, and are pursuing the inter-governmental model. This should allow the British to take part, thereby strengthening the venture.

citer l'article

Daniela Schwarzer, What can the European political community achieve?, Oct 2022,