Avoiding a Requiem for the WTO

Issue

Issue #2Auteurs

Bernard Hoekman , Petros C. Mavroidis

21x29,7cm - 186 pages Issue #2, Spring 2021 24€

Governing Globalization

Although the WTO has been relatively effective in overseeing the implementation of the multilateral agreements concluded during the Uruguay Round, with some notable exceptions, including the Agreement on Trade Facilitation and the Information Technology Agreement, WTO members have not managed to conclude new agreements to liberalize trade in goods and services. This has had serious repercussions. For one, it shifted the focus of many members to bilateral and regional trade cooperation. For another, it has meant that the WTO has not played a significant role in defusing and addressing the trade conflict between the US and China.

The WTO was largely ‘missing in action’ during the first stages of the global COVID-19 pandemic – many members resorted to unilateral imposition of export restrictions for medical supplies and personal protective equipment. Suggestions to react fell on deaf ears: cooperation on trade in vaccines 1 ; support global value chains producing critical supplies 2 ; agreement to govern restrictions during a global public health crisis 3 . Some WTO members have made proposals in this vein, but to date no new agreements on such matters have been considered 4 . Absent progress on restoring the role of the WTO as a forum for cooperation on trade there is little prospect that the organization can play a significant role in helping to address major trade tensions between the large trading powers and move forward in guiding the use of trade and trade policy in addressing global market failures (climate change) and helping member governments to identify and implement good regulatory practices to support sustainable development objectives.

Although many WTO members tend to view matters through a ‘US’ or a ‘China lens’, it is important to recognize that the need for international cooperation spans a range of issues areas that are salient to a broad cross-section of the WTO membership. Whether the political will exists to reengage multilaterally and pursue WTO reform is an open question. We discuss five areas of WTO reform 5 : (1) revisiting the working practices of the organization; (2) monitoring and evaluation; (3) preparing negotiation of new agreements; (4) reforming the WTO dispute settlement system; and, last but not least (5) addressing what Wu has termed the ‘China Inc.’ 6 problem 7 .

1. Working Practices

The consensus decision-making, and a “member-driven” governance model have reduced the effectiveness of the WTO 8 . While appropriate for adoption of results of substantive negotiations, WTO working practices have been abused by members to impede the functioning of WTO bodies. We should differentiate between day-to-day activities of WTO bodies and negotiation and adoption of substantive disciplines. Consensus legitimizes conclusions on substantive matters, but it should not enable countries to block agreements that bind only signatories. Nor should consensus apply to matters such as setting the agenda of WTO committee meetings 9 . Increasing interaction with stakeholders and opening the WTO to greater participation by nongovernmental entities are important areas for reform.

2. From Notification & Review to Monitoring & Evaluation

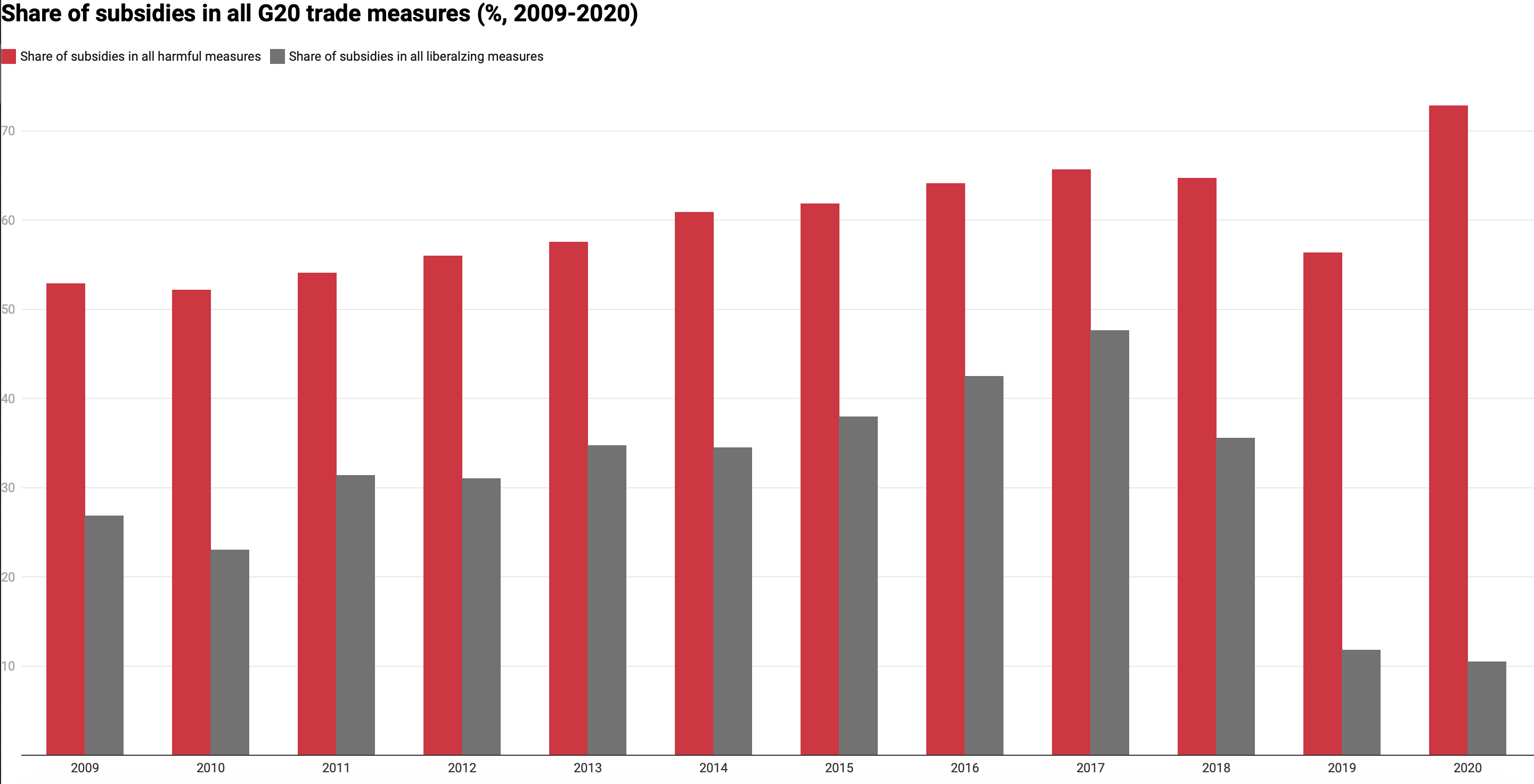

As things stand, monitoring is entrusted to members, who supply information through notifications, complemented by WTO Secretariat preparation of periodic Trade Policy Reviews (TPRs) for all members. Cross-notifications of Chinese subsidies by the United States, for example, make clear that the notification process results in a (very) incomplete picture in some areas of trade policy 10 . Independent monitoring by the Global Trade Alert initiative reveals many more subsidies. Although many subsidies are removed each year, more harmful measures are introduced each year than are removed, and the gap has been increasing (Figure 1). The WTO Secretariat should be mandated to compile publicly available information on national policies 11 . The need goes beyond subsidies, and includes policies affecting investment and trade in services and cross-border data flows. On services, for example, the WTO only reports data for a subset of the membership 12 .

Source : Global Trade Alert. https://www.globaltradealert.org/.

The WTO cannot outsource this core function but would benefit from cooperating with other organizations in this effort (IMF, World Bank, UNCTAD, ITC and OECD). A focal point for such collaboration could be the G20 Trade and Investment Working Group, in which all these organizations participate.

3. Negotiating Anew

In 2020, the Ottawa Group requested analysis of adopted COVID-19 measures 13 . The WTO Secretariat is prohibited from expressing a view whether policies are consistent with WTO rules, and is not tasked with assessing the ex-post impacts of WTO agreements or the cross-border spillover effects. Fiorini et al. found that evaluation – as distinct from monitoring – was ranked last as a priority for the next DG 14 . Creating more space for the Secretariat to analyze the global economic effects of policies affecting competitive conditions on markets, by cooperating with other institutions, would help determine whether policies cause spillovers that are systemic in nature 15 . Greater use of ‘thematic sessions’ of WTO bodies – in which external actors are invited to participate and the agenda includes matters that are not (yet) subject to multilateral rules – and overcoming silo problems by establishing dedicated working parties spanning all WTO bodies that deal with different dimensions of a policy area are pragmatic ways of fostering deliberation. Greater direct involvement in the operation of the WTO by the business community can help keep the WTO relevant by providing officials with up-to-date information from the core constituency they represent 16 .

In late 2017 many WTO members launched plurilateral initiatives to define good practices and new rules in four areas: e-commerce, investment facilitation, services domestic regulation and supporting micro, small and medium-sized enterprises to exploit trade opportunities. Dubbed Joint Statement Initiatives (JSIs), these plurilateral initiatives are a positive development 17 . Plurilateral domain-specific cooperation that focuses on policies underlying current trade tensions offers a means for WTO members to engage meaningfully with like-minded trade partners on subjects of common interest. The MFN constraint may of course block plurilateral cooperation because of free riding concerns. Creating a legal basis in the WTO to incorporate and govern discriminatory agreements is an important area for reform 18 . Open plurilateral agreements (OPAs) that are applied on an MFN basis, as argued by Hoekman and Sabel, will help assure non-signatories of their compatibility with the WTO 19 .

Special and differential treatment (SDT) of developing countries means that developing nations may offer less than full reciprocity in trade negotiations and claim greater freedom to use certain trade policies than high-income countries. Outside the group of UN-defined LDCs, there are no criteria that define what constitutes a developing country. SDT has been used, abused, and created problems. The Trade Facilitation Agreement (TFA) allows scheduling of commitments by developing countries and links implementation to technical assistance. Low et al. go further and argue for a new bargain on what differentiation means, designing SDT in terms of specific individual country needs at the sectoral or activity level 20 .

4. Dispute Settlement

The WTO includes independent, third-party adjudication of trade disputes reflected in the principle of de-politicized conflict resolution 21 . If the prospects of effective enforcement decline, there will serious negative consequences for future rule-making efforts in the WTO. Action to address the weaknesses of the Dispute Settlement Understanding (DSU) is therefore a priority area of WTO reform. Since its establishment in 1995, some 600 bilateral trade disputes (598 as of end December 2020) have been adjudicated. The International Court of Justice (ICJ), a state-to-state court that adjudicates disputes in all areas of international law, has only addressed 178 disputes since 1947 22 . Some members, notably the US, have been critical of the system, alleging that the Appellate Body (AB) has too frequently overstepped its mandate. The antidumping zeroing case law, the core US concern, AB rulings on the use of safeguard actions, and as discussed by Ahn 23 , the case law on “public body” all contributed to the doubts about the quality of outcomes. The objective function of courts is to make law predictable. There is often, no predictability generated by AB rulings in this area. The AB ceased operations in December 2019 because of US refusal to agree to appoint new AB members and/or re-appoint incumbents. Resolution of the crisis requires reform of how the system works. As of October 2020, fourteen appeals were pending before the dysfunctional AB 24 , raising the question what the status is of the associated panel reports 25 .

WTO members most concerned with effective dispute settlement need to launch negotiations on specific procedural dispute settlement reforms. These can build on the ‘Walker principles’ 26 that address core US concerns, e.g., that adjudicators do not exceed their mandate and engage in rulemaking. Reform efforts should include a focus on the first stage panel process and the role of the WTO bodies and the Secretariat in helping to defuse and resolve disputes. Wauters 27 , echoing previous analysts 28 , characterizes the Secretariat as the “invisible experts” who influence the preparation of reports. This must change. The key need in any reform process is to maintain the de-politicized nature of WTO dispute adjudication. This need not require an appeals board 29 , even though most WTO members prefer to maintain the two-stage process 30 . And there is scope for constructive engagement under WTO auspices, which could be emulated elsewhere: ‘specific trade concerns’ (STCs) in committee deliberations 31 provides an illustration 32 .

5. China Inc.

As Mavroidis and Sapir note 33 , China’s accession, hailed initially as a milestone for the multilateral trading system, became a source of acrimony 34 . The US especially has raised a series of complaints before the WTO, mostly dealing with the role of the state in the workings of the economy – what Wu 35 has termed the China Inc. problem. The behavior of state-owned enterprises (SOEs) and measures requiring transfer of technology have been central to US concerns. Furthermore, China has not changed its policies because of US measures, or the announced EU White Paper on subsidies 36 . If the major trade powers do not (cannot) negotiate new, specific disciplines for subsidies, SOEs and transfer of technology, the various reform areas discussed above will have much less salience.

Conclusion

The question looking forward is whether rulemaking, which increasingly has shifted to deep regional trade agreements 37 can occur under WTO auspices. For the WTO to open its door to deeper forms of cooperation the membership must accept variable geometry. The new DG has an important role to play in this regard.

Notes

- See, T. Bollyky and C. Bown, “The Tragedy of Vaccine Nationalism: Only Cooperation Can End the Pandemic,” Foreign Affairs, 2020 https://www.foreignaffairs.com/articles/united-states/2020-07-27/vaccine-nationalism-pandemic.

- See, M. Fiorini, B. H. Hoekman and A. Yildirim, “COVID-19: Expanding access to essential supplies in a value chain world,” in R. Baldwin and S. Evenett (eds.), COVID-19 and Trade Policy: Why Turning Inward Won’t Work, London: CEPR Press, 2020.

- See, S. Evenett and L. A. Winters, “Preparing for a Second Wave of COVID-19: A Trade Bargain to Secure Supplies of Medical Goods”, 2020: https://www.globaltradealert.org/reports/52.

- See e.g., Canada. 2018. Strengthening and modernizing the WTO. JOB/GC/201, 24 September; Canada. 2018b. Strengthening the deliberative function of the WTO. JOB/GC/211, 14 December; China. 2019. China’s Proposal on WTO Reform. WT/GC/W/773, 13 May; China. 2019. China’s Proposal on WTO Reform. WT/GC/W/773, 13 Ma; European Union. 2018. Concept Paper on WTO Modernization, at https://trade.ec.europa.eu/doclib/docs/2018/september/tradoc_157331.pdf.

- See, https://globalgovernanceprogramme.eui.eu/research-project/revitalizing-multilateral-governance-at-the-wto-2-0/.

- See M. Wu, “The ‘China, Inc.’ Challenge to Global Trade Governance,” Harvard International Law Journal, 2016, 57: 1001-63.

- See, M. Bronckers, “Trade Conflicts: Whither the WTO?” Legal Issues of Economic Integration, 47(3): 221–244; S. Charnovitz “Solving the Challenges to World Trade” 2020: https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=3736069; O. Fitzgerald, (ed.), Modernizing the World Trade Organization, Waterloo: CIGI, 2020. See also, bringing together a compilation of suggestions for a post-COVID-19 work program, S. Evenett and R. Baldwin (eds.), Revitalising Multilateralism: Pragmatic ideas for the new WTO Director-General, London: CEPR Press, 2020.

- See, B. M. Hoekman. 2019. “Urgent and Important: Improving WTO Performance by Revisiting Working Practices,” Journal of World Trade, 53(3): 373-94.

- The 2007 Warwick Commission report, The Multilateral Trade Regime: Which Way Forward? proposes greater recourse to critical mass-based deliberation and proposes that WTO members be called upon to explain their reasons for objecting to proposed agenda items. See https://warwick.ac.uk/research/warwickcommission/worldtrade/report.

- See, R. Wolfe, “Is World Trade Organization Information Good Enough? How a Systematic Reflection by Members on Transparency Could Promote Institutional Learning”, Queen’s University – School of Policy Studies, 2018: https://ssrn.com/abstract=3299015.

- This has begun to be done – see e.g., WTO, Overview of developments in the international trading environment, WT/TPR/OV/23, Geneva: WTO, 2020.

- See, B. M. Hoekman and B. Shepherd, “Services Trade Policies and Economic Integration: New Evidence for Developing Countries,” World Trade Review, 2020; R. Wolfe. 2021. “Yours Is Bigger Than Mine! Could an Index Like the PSE Help in Understanding the Comparative Incidence of Industrial Subsidies?”, The World Economy, forthcoming.

- See, Ottawa Group. 2020. “COVID-19 and Beyond: Trade and Health,” Communication from Australia, Brazil, Canada, Chile, the European Union, Japan, Kenya, Republic of Korea, Mexico, New Zealand, Norway, Singapore and Switzerland, WT/GC/223, November 24 2020.

- See, M. Fiorini, B. M. Hoekman, P.C. Mavroidis, D. Nelson and R. Wolfe, “Stakeholder Preferences and Priorities for the Next WTO Director General”, Global Policy, 2021. Note that on February 15, 2021, the General Council agreed by consensus to select Ngozi Okonjo-Iweala of Nigeria as the organization’s seventh Director-General.

- See, B. M. Hoekman and D. Nelson, “Rethinking International Subsidy Rules,” The World Economy, 43(12): 3104-32, 2020.

- See, E. Alben and L. Brown, “Is the WTO in Sync with the Business Community?”, Global Policy, 2021. For specific proposals on mechanisms to do this see C. Findlay and B. Hoekman, “Value chain approaches to reducing policy spillovers on international business,” Journal of International Business Policy, 2020.

- Note however that the legality of JSIs has recently been challenged in a communication signed by India and South Africa, see WTO Doc. WT/GC/W/819 dated Feb. 19, 2021.

- See, B.M. Hoekman and P. C. Mavroidis, “Embracing Diversity: Plurilateral Agreements and the Trading System,” World Trade Review, 2015, 14(1): 101-16. See also, M. Bronckers. 2020. “Trade Conflicts: Whither the WTO?”, Legal Issues of Economic Integration, 2015, 47(3): 221–244.

- See, B. M. Hoekman and C. Sabel, “Plurilateral Cooperation as an Alternative to Trade Agreements: Innovating One Domain at a Time”, Global Policy, 2021.

- See, P. Low, H. Mamdouh and E. Rogerson, Balancing Rights and Obligations in the WTO–Shared Responsibility, Stockholm: Government of Sweden, 2018.

- See, B. M. Hoekman and P. C. Mavroidis. 2020. “To AB or Not to AB? Dispute Settlement in WTO Reform”, Journal of International Economic Law, 2020, 23(3): 703-22.

- International Court of Justice: https://www.icj-cij.org/en/cases.

- See, D. Ahn, “Why Reform is Needed: WTO ‘Public Body’ Jurisprudence”, Global Policy, 2021./

- See, B. M. Hoekman and P. C. Mavroidis, “Preventing the Bad from Getting Worse: Is it the End of the World (Trade Organization) As We Know it?”, European Journal of International Law, forthcoming.

- In response to the demise of the AB the EU developed the MPIA (Multi-Party Interim Appeal Arbitration Arrangement). This commits signatories that are complainants or respondents in panels to either accept a panel report or to use the MPIA to appeal findings through a process that closely mirrors what the AB would do. Participation is open to any WTO member. At the time of writing only 23 WTO members had joined the MPIA, including the EU and China.

- D. Walker, Informal Process on Matters Related to the Functioning of the Appellate Body – Report by the Facilitator, H.E. Dr. David Walker (New Zealand), OMC, 2019.

- See, J. Wauters. “The Role of the WTO Secretariat in Dispute Adjudication”, Global Policy, 2021.

- See, H. Nordström, “The WTO Secretariat in a Changing World”, Journal of World Trade, 2005, 39: 819-853. See, also J. Pauwelyn and K. Pelc., “Who Writes the Rulings of the World Trade Organization? A Critical Assessment of the Role of the Secretariat in WTO Dispute Settlement”, 2019: https://ssrn.com/abstract=3458872.

- See, B. M. Hoekman and P. C. Mavroidis, “To AB or Not to AB? Dispute Settlement in WTO Reform,” Journal of International Economic Law, 2020, 23(3): 703-22.

- This is a clear finding emerging from the survey of practitioner views on the DSU and the AB crisis by M. Fiorini, B. Hoekman, P. C. Mavroidis, M. Saluste and R. Wolfe, “WTO dispute settlement and the Appellate Body: Insider perceptions and Members’ revealed preferences,” Journal of World Trade, 2020, 54(5): 667-98. Compare R. Howse, “Appointment with Destiny: Selecting WTO Judges in the Future”, Global Policy, 2021.

- See, M. Karttunen, Transparency in the WTO SPS and TBT Agreements: The Real Jewel in the Crown, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2020.

- A corollary of the STC process is that members have a greater incentive to notify new measures coming under the purview of the TBT- and SPS committees. The notification track record in these areas is good as is reflected in the databases that are maintained by the Secretariat on new TBT and SPS measures M. Karttunen, “Transparency in the WTO SPS and TBT Agreements: The Real Jewel in the Crown”, Cambridge University Press, 2020; R. Wolfe, “Reforming WTO Conflict Management: Why and How to Improve the Use of Specific Trade Concerns,” Journal of International Economic Law, forthcoming.

- See, P.C. Mavroidis and A. Sapir, “All the Tea in China: Solving the ‘China Problem’ at the WTO”, Global Policy, 2021.

- Since 2011, under President Xi, there has been a shift towards increasing the role of the state in the economy.

- See, M. Wu, “The ‘China, Inc.’ Challenge to Global Trade Governance,” Harvard International Law Journal, 2016, 57: 1001-63.

- See, European Commission, White Paper on levelling the playing field as regards foreign subsidies, Brussels, June 17 2020 COM(2020) 253 final: https://ec.europa.eu/competition/international/overview/foreign_subsidies_white_paper.pdf.

- See e.g., A. Mattoo, N. Rocha and M. Ruta (Eds.), Handbook of Deep Trade Agreements, Washington, DC: World Bank, 2020.

citer l'article

Bernard Hoekman, Petros C. Mavroidis, Avoiding a Requiem for the WTO, Aug 2021, 95-97.

à lire dans cette issue

voir toute la revue