Regional election in Hauts-de-France, 20-27 June 2021

Issue

Issue #2Auteurs

Tristan Haute , Marie Neihouser

21x29,7cm - 167 pages Issue 2, March 2021 24,00€

Elections in Europe : June 2021 – November 2021

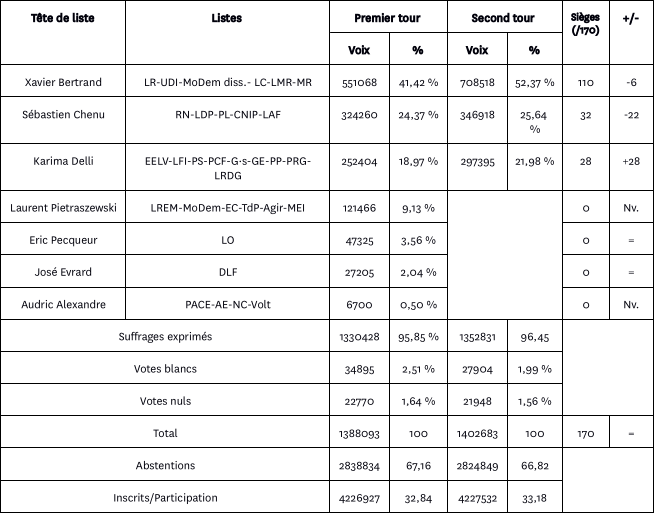

On June 20 and 27, 2021, the citizens of Hauts-de-France were called to the polls of the regional election. This election was marked by very low turnout: 32.84% in the first round and 33.18% in the second round compared to 54.81% and 61.24% respectively in the previous election in December 2015.

1

While the election was held amid the Covid-19 crisis, the voter demobilization, also observed in the rest of the country but even more pronounced in Hauts-de-France, was nevertheless not directly related to the epidemic risk. In June 2021, unlike in the 2020 municipal election (Haute et al. 2021), demobilization was not greater among the most at-risk elderly, unvaccinated people or antivaccinationists than in the general population (Haute 2021). While the vaccine uptake was associated with higher voter turnout (Jaffré 2021), this stands also true for the municipal election (Ward et al. 2020). Voter turnout in this regional election was in fact dependent on the same social and political logic as in the previous 2015 election (Gougou 2017a: 52-53), with a much more massive demobilization of young people, the working classes, and voters least interested in politics (Haute 2021; Jaffré 2021), three categories who traditionally participate less than the average voter.

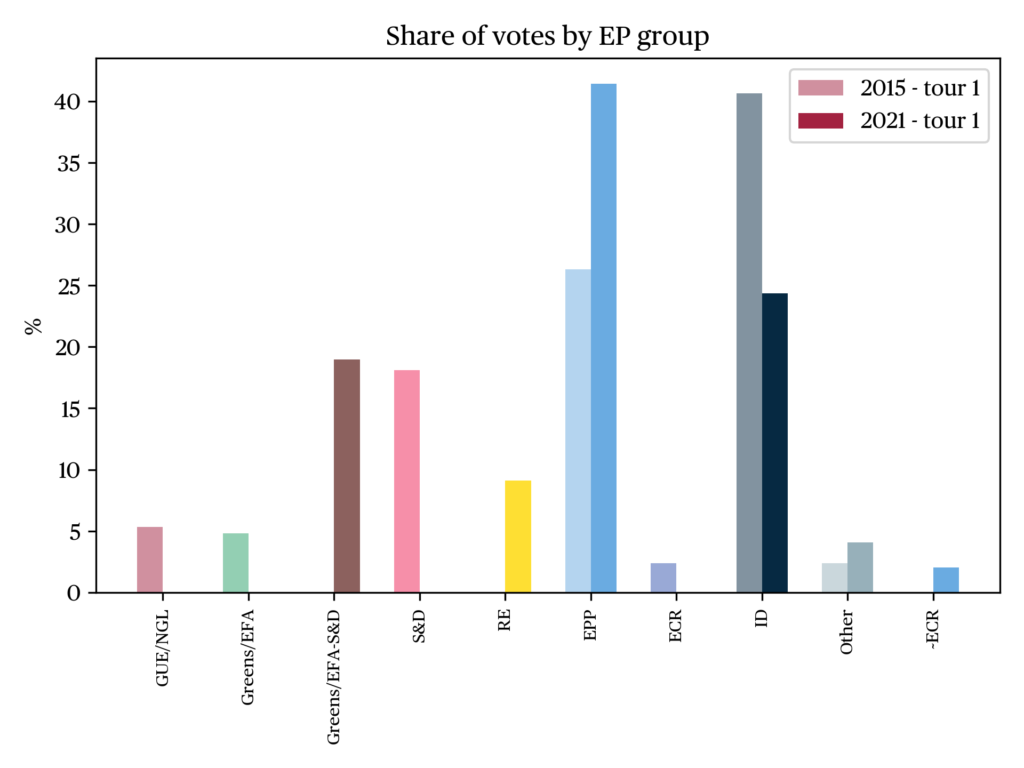

A political landscape marked by the decline of the left and the success of the far right

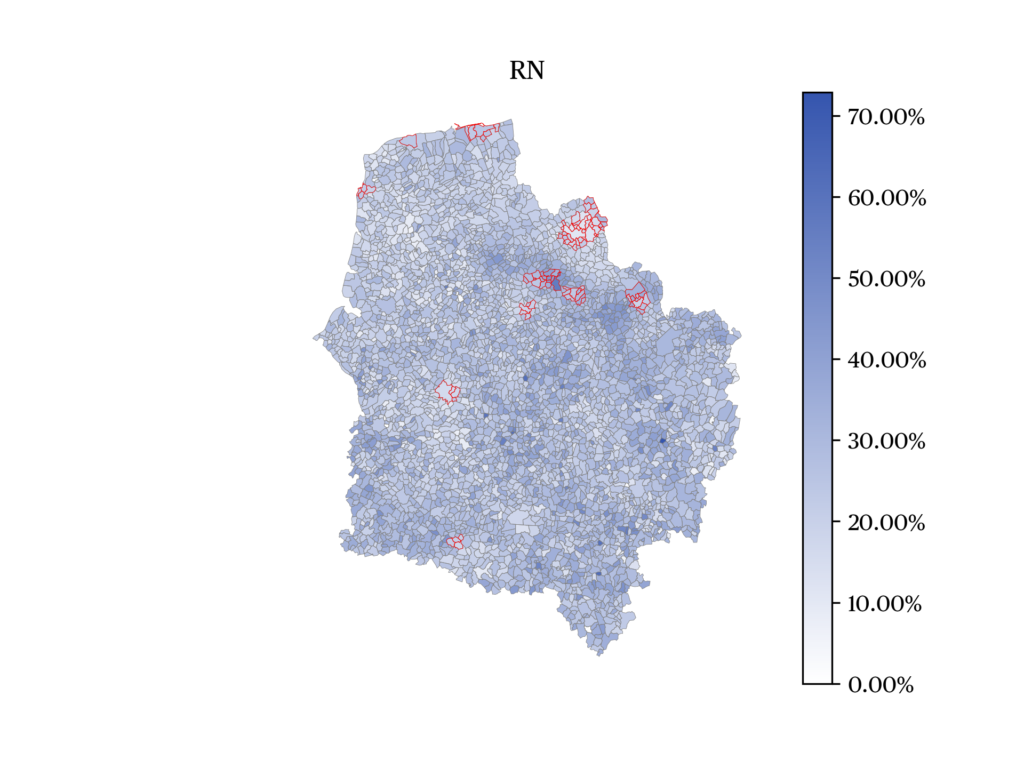

The Hauts-de-France region (6 million inhabitants), which was formed in the 2015 merger of the former Nord-Pas-de-Calais (4 million inhabitants) and Picardie (2 million) regions, is a place of historical left-wing dominance, particularly in the Nord and Pas-de-Calais departments. However, the Socialist Party (PS, S&D) and the French Communist Party (PCF, GUE/NGL), which had many strongholds in the region, have seen their electoral results decline sharply in recent decades. In 2015, the left lost control of the region and 4 of the 5 departments, retaining only a thin majority in Pas-de-Calais. At the same time, the National Front (FN), which has become the National Rally (RN, ID), has obtained results above its national average in the region since the 1980s. From the end of the 2000s, the FN developed its local presence in the former mining basin, but also in more rural areas in the east of the region. Between 2014 and 2020, the FN won 3 municipalities, 13 cantons and 5 legislative districts in the region. In the first round of the 2017 presidential election, Marine Le Pen, who was both the candidate and leader of the FN, scored nearly 10 percentage points higher in the region than its national average (31% against 21.30% of votes cast).

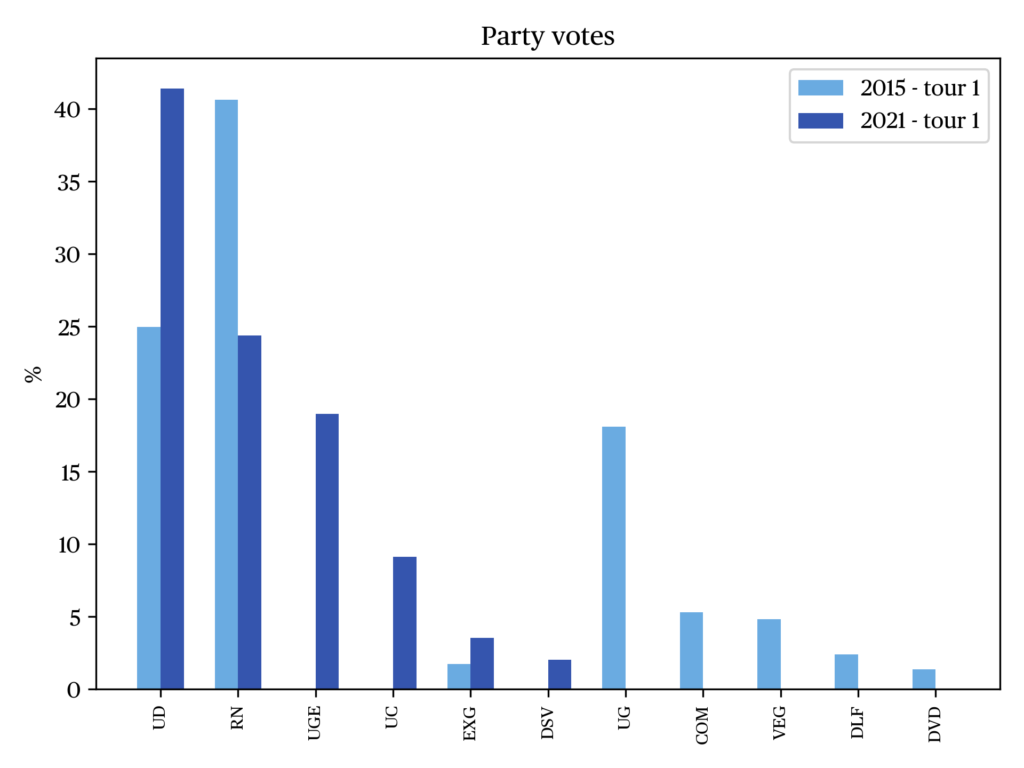

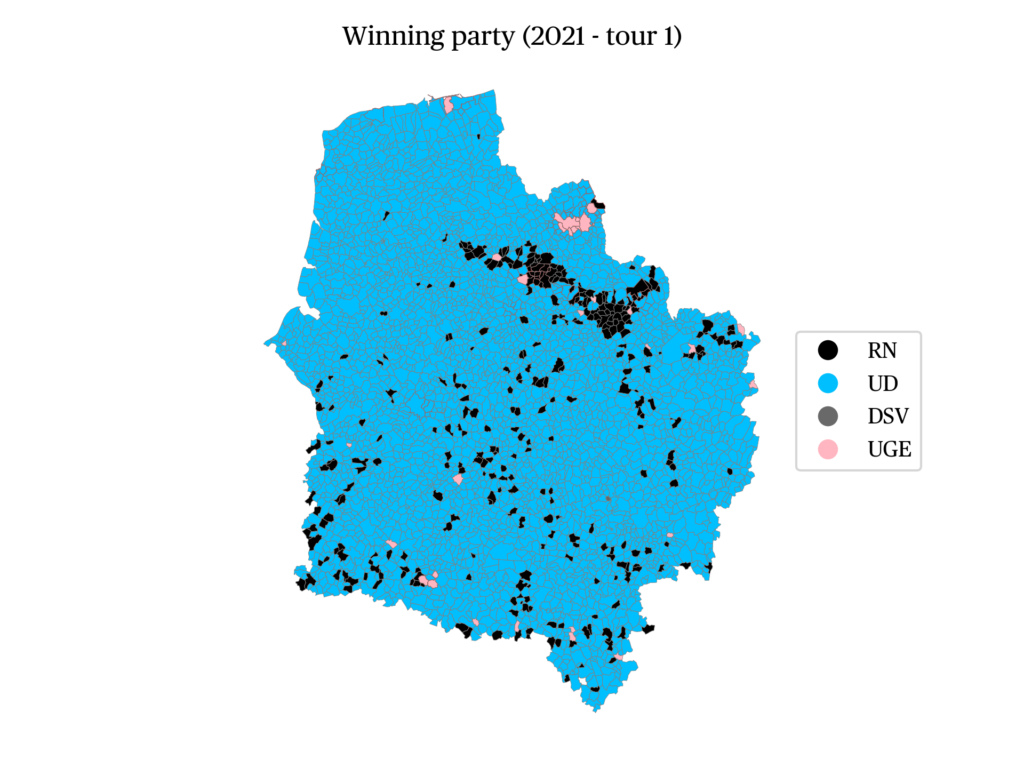

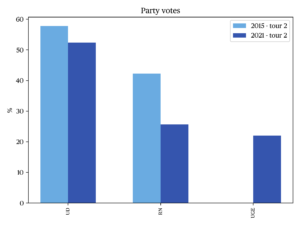

In 2015, as the new region was only weakly identified between the populace — in fact, it did not even have a name —, the main issue at stake in the regional election was the possible victory of the Le Pen list (FN), which gave rise to a highly nationalized campaign (Lefebvre 2016) and generated greater electoral mobilization than at the national level. The FN list gathered a plurality of votes in the first round (40.64%) (see Figure a) but failed in the second round (42.23%) against the united right and center parties led by Xavier Bertrand (57.77%) (see “the data”). The latter, taking advantage of the demobilization of voters favourable to the left, particularly among the working classes (Gougou 2017a: 50-51), in the logic of “intermediate elections” (Parodi 1983), came second in the first round with 24.97% of the vote. The left, divided between three lists, was then forced to withdraw from the second round in favor of Xavier Bertrand to block the extreme right from seizing control of the regional executive (Dolez & Laurent 2016).

In 2021, the situation had changed little. The RN, led by deputy Sébastien Chenu, was counting on winning the region, especially since the polls prior to the first round showed it neck and neck with incumbent Bertrand (32% against 33% on June 16, 2021) (OpinionWay 2021). The latter, making his re-election at the regional elections a prerequisite for his presidential ambitions for 2022, had managed to set up a list of the united right and center parties under his own leadership despite having himself left his former party, the Republicans (LR, EPP). President Macron’s La République en Marche (LREM, Renew) presented a list led by Secretary of State Laurent Pietraszewski, in charge of an unpopular pension reform, on which 4 other members of the government were also running. Finally, the left, having drawn conclusions from their 2015 defeat, presented a list in the first round led by ecologist MEP Karima Delli and including members from Europe-Ecology-The-Greens (EELV, Greens/EFA), Unbowed France (LFI, GUE/NGL), the PCF and the PS.

The campaign was of very low intensity due to the health context. The main issue addressed was insecurity, even though the region’s competencies in this area are limited. A second issue, which was more local but not solely related to the region, was related to the establishment of wind farms in certain rural areas of Hauts-de-France, which was strongly criticized by both far-right and right-wing parties (Patinaux 2022). Bertrand’s declared presidential ambition and the massive presence of ministers on the LREM list, including Justice Minister Éric Dupont-Moretti and Interior Minister Gérald Darmanin, further contributed to nationalizing the campaign. However, unlike in 2015, the risk of the RN winning the region appeared much lower (OpinionWay 2021), which did not help mobilize voters.

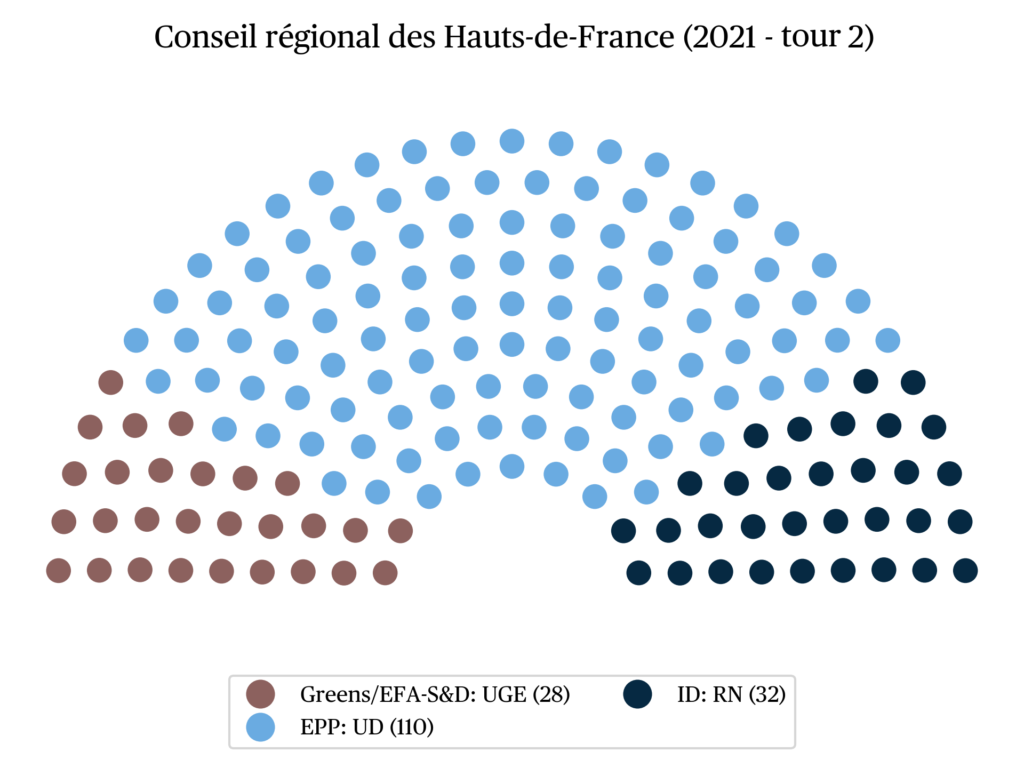

Unexpected outcomes

In the evening of the first round of voting in 2021, Bertrand (LR) came out on top by a wide margin (41.42%), clearly ahead of Chenu (RN, 24.37%), Delli (United left and Ecologists, 18.97%) and Pietraszewski (LREM, 9.13%) (see “thre data”). In the second round, Bertrand was overwhelmingly re-elected with 52.37% of the votes cast, while the RN and the left improve their scores only marginally with 25.64% and 21.98% respectively (see Figure b).

The presidential majority list, eliminated from the second round as in many regions, was a victim of the unpopularity of the government. The LREM list had to face fierce competition from the Bertrand list within its own electoral base. Indeed, the latter enjoyed a high profile and cultivated a certain localism despite his presidential ambitions. This is evidenced by his ability to bring together on his list the different currents of the right and center as well as representatives of “civil society,” particularly from the business world. On the left, while the score of the united list in the first round allowed it to advance to the second round and regain seats in the regional assembly (see Figure b), it was nevertheless much lower than the total votes of the three left-wing lists in 2015 (-9.30 points), which testifies to the inability of the United left and Ecologists’ list to stem the demobilization of traditionally supportive social groups (Gougou, 2017a). At the same time, as in other regions, the RN was also impacted by a massive electoral demobilization, which seems unusual (Gougou 2017a). Many voters from the working classes often facing precariousness who had turned to the FN in 2015 (Mayer 2017) have stayed away from ballot boxes in 2021. Moreover, Bertrand was able to benefit from both a much better notoriety than his other competitors and a more mobilized electoral base: right-wing voters are most represented among older, more educated, and higher-income groups (Sauger 2017: 64-65), which had the highest turnout rates in June 2021. This combination of high visibility and lower demobilization of their electoral bases explains why, at the national level, all outgoing presidents, both right-wing and socialist, have been largely re-elected. Indeed, it should be remembered that one of the rare distinctive features of PS voters compared to those of other left-wing parties is their older age (Gougou 2017b: 58), an important difference at a time when the ballot box is becoming increasingly grey (Haute & Tiberj 2022).

Persistent electoral contrasts

The Hauts-de-France region is marked by electoral contrasts that reflect not only political legacy — as evidenced by the RN’s strength in the former mining basin or the PCF’s in the Valenciennes region — but above all demographic, economic and social inequalities (Rivière et al. 2012). Indeed, while the region has a younger, more working-class, and a somewhat less educated population than the rest of the country, it remains nonetheless very heterogeneous.

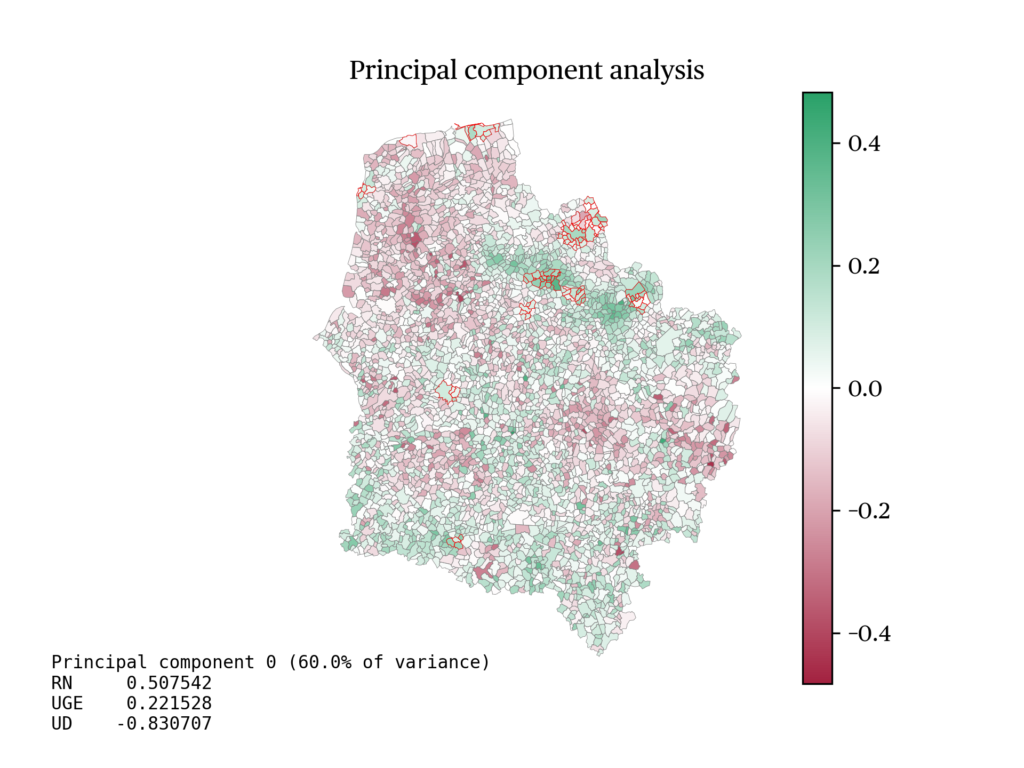

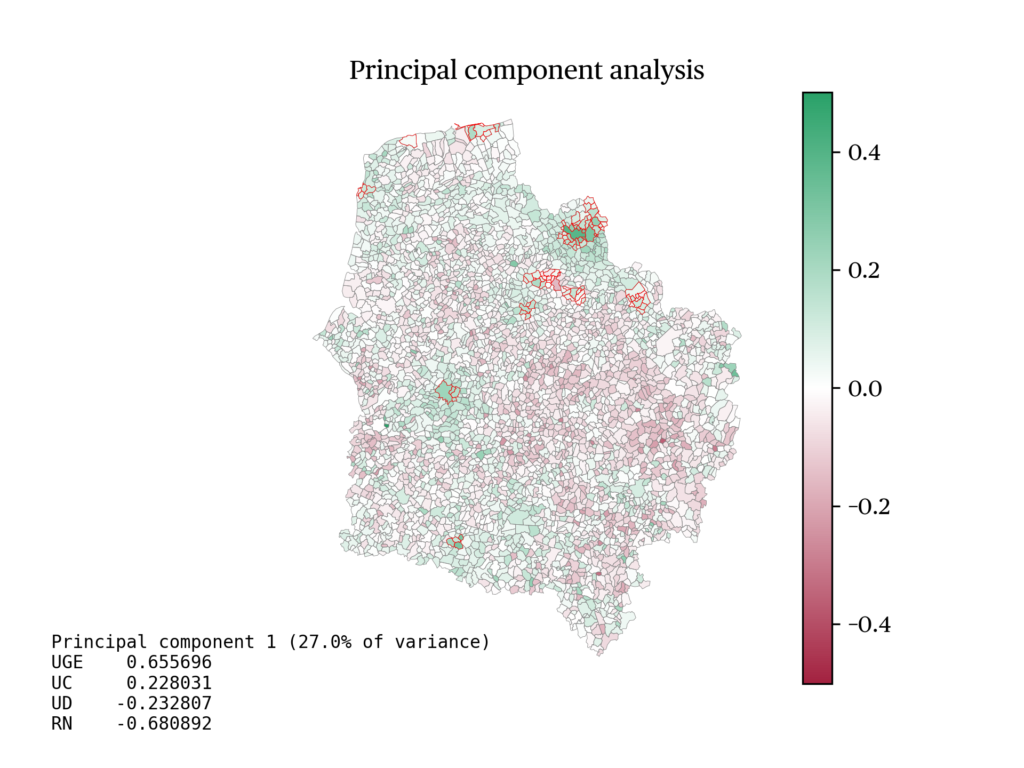

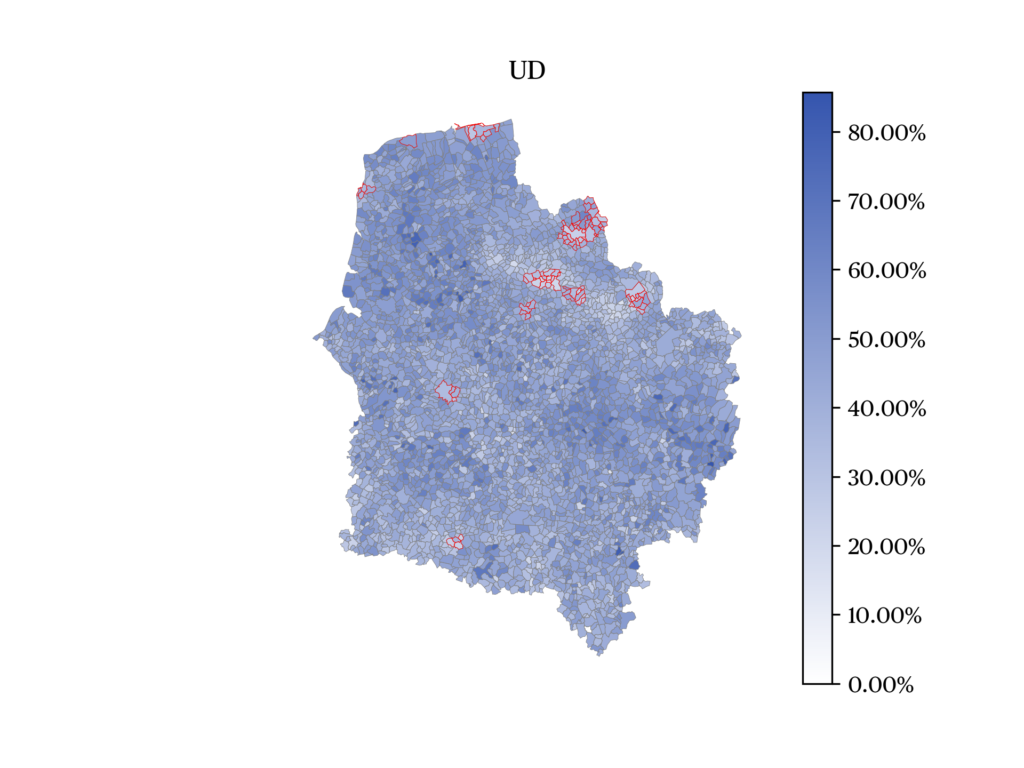

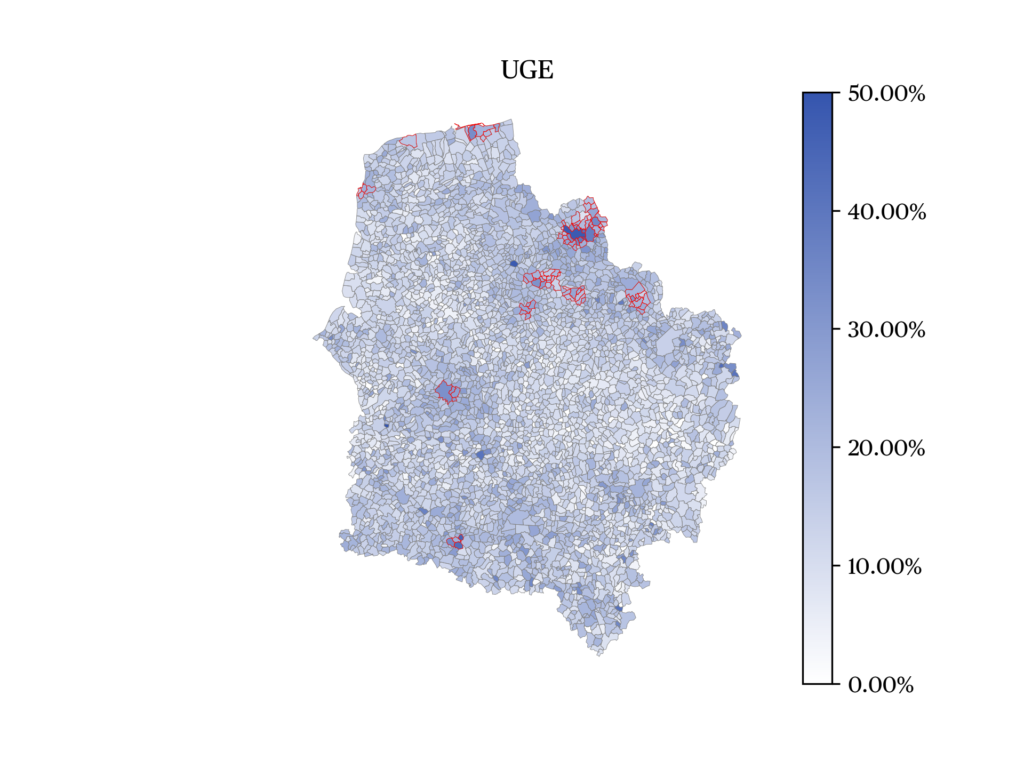

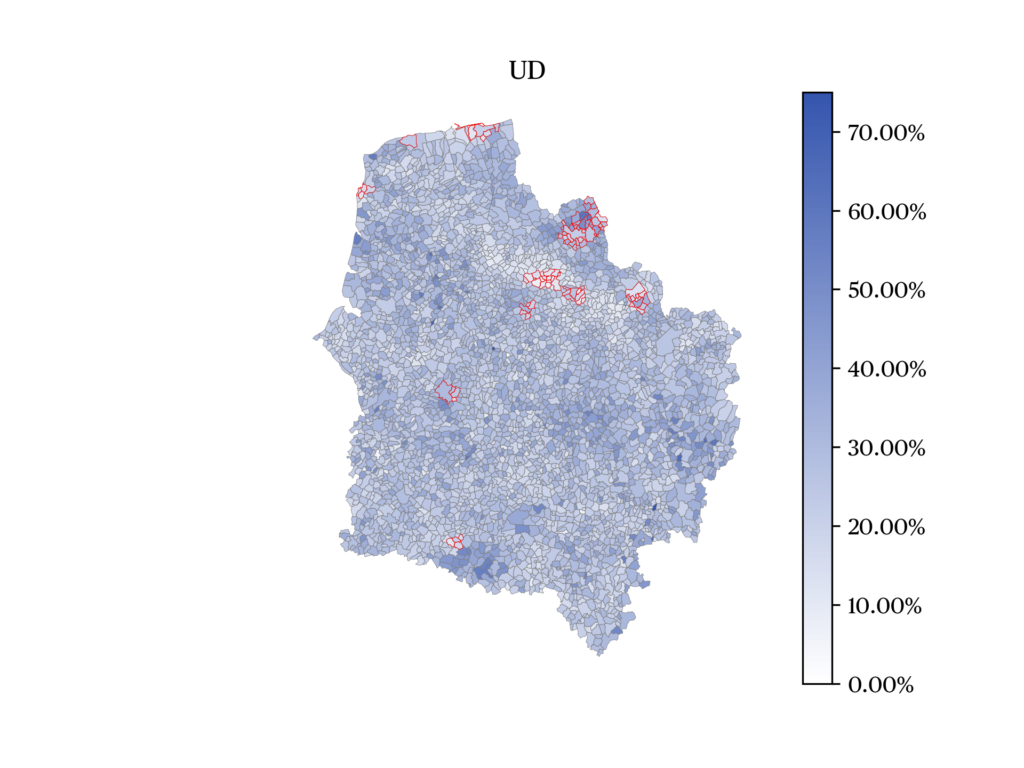

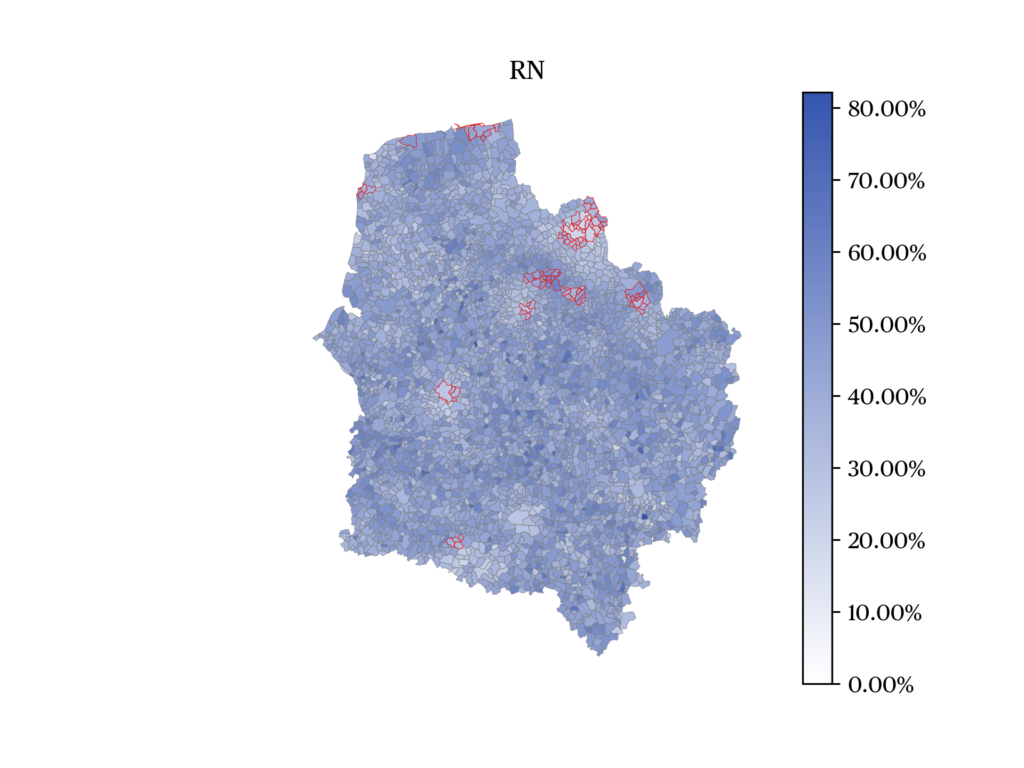

In 2021, two main socio-spatial cleavages appear to structure voting choices. The first one opposes the communes of the former mining basin to the region’s numerous rural communes. While the former suffered from deindustrialization and mass unemployment, leading to the RN and the left obtaining results higher than their regional averages (Wadlow 2021), the latter are home to an older population less confronted with job insecurity, allowing right-wing parties to obtain results higher than their regional average (see Figure c, left). A second one cleavage opposes urban areas — around Lille and Amiens in particular — which, although very heterogeneous (Rivière et al. 2012), concentrate a more educated population that votes more for the center or the left, with peripheral territories where the working classes are relegated, particularly the east of the region, where the results of the right wing and the RN are higher than their regional averages (see Figure c, right).

Despite the evolution of the results of the different parties between 2015 and 2021, the electoral geography has changed little, showing that it depends less on the presence of specific candidates than on long-term social and political logic. This is the case for the Bertrand vote (Figure d, center). For the RN, the two maps are very similar (Figure d, left); the party manages to limit its decline in the two communes of the mining basin that it controls (Hénin-Beaumont since 2014 and Bruay-la-Bussière since 2020) (Wadlow 2021), but not in the other constituencies or cantons gained in 2015 and 2017. The electoral impact of its local presence in these territories, while not negligible, remains therefore limited. Finally, the United left and Ecologists’ list (Figure d, right) obtained results higher than its regional average in Lille (52.4% of the vote) and its periphery, in the few other large cities of the region (Amiens, Dunkirk, Boulogne-Sur-Mer) as well as in the mining basin. While similar trends could already be observed in 2015 for the PS and EELV lists, the case of the PCF was different. In 2015, the PCF had especially mobilized in their popular strongholds of Valenciennes and the mining basin, two areas in which the left-wing vote was not always above average in 2021. The United left and Ecologists’ list therefore seems to have had great difficulty in mobilizing former PCF voters.

Conclusion and perspectives

While some parties and candidates saw the regional elections in the Hauts-de-France as a “launching pad” for the 2022 presidential election, it must be said that the results of the election fell short of their expectations. The inability of the United left and Ecologists to stimulate a mobilization dynamic only confirmed how divided the left was. Similarly, the failure of the RN, who proved unable to conquer the region and to remobilize voters who had turned to them in 2015, has weakened the candidacy of Le Pen, who is now competing with fellow far-right candidate Éric Zemmour (Reconquest). Finally, despite winning the election by a large margin, Bertrand did not set in motion a national dynamic that would have allowed the right’s potential electoral base, who has been shrinking socially and politically since 2017, to expand again (Desplaces et al. 2021). These thwarted prospects are linked to the very low turnout recorded during this election. This low participation in turn reflects the difficulty of parties and candidates to mobilize citizens who are the most distant from politics, or at least partisan politics. This election highlights the political imbalances that result from massive electoral demobilization, which benefits the parties and candidates (in this case Bertrand), whose potential voters are keen to participate.

Literature

Desplaces, P., Dorlencourt, J., Haute, T. & Neihouser, M. (2021, 26 December). Ce que l’analyse des sondages nous dit de la candidature avortée de Xavier Bertrand. The Conversation. Online.

Dolez, B. & Laurent, A. (2016). Nord-Picardie, tournant historique : victoire de Bertrand. Revue politique et parlementaire, 1078, pp. 119-138.

Eliazord, G. & Haute, T. (2021, 5 July). Départementales dans le Nord et le Pas-de-Calais : sous l’abstention, la stabilité ? DailyNord. Online.

Gougou, F. (2017a). Les dynamiques de la participation. In Gougou, F. & Tiberj, V., La déconnexion électorale. Paris: Fondation Jean Jaurès, pp. 47-54.

Gougou, F. (2017b). Les électeurs de gauche. In Gougou, F. & Tiberj, V., La déconnexion électorale. Paris: Fondation Jean Jaurès, pp. 55-60.

Haute, T. & Tiberj, V. (2022). Extinction de vote ? Paris: Presses universitaires de France.

Haute, T. (2021, 23 June). Abstention : au-delà de la crise sanitaire, les vraies raisons de la démobilisation. The Conversation. Online.

Haute, T., Kelbel, C., Briatte, F. & Sandri, G. (2021). Down with Covid: Patterns of Electoral Turnout in the 2020 French Local Elections. Journal of Elections, Public Opinion and Parties, 31 (1), pp. 69-81.

Jaffré, J. (2021, June). Participation régionale, adhésion vaccinale : même orientation. Note du Baromètre de la confiance politique, Sciences Po / CEVIPOF, vague 12bis.

Lefebvre, R. (2016). Les élections régionales en Nord-Pas-de-Calais-Picardie. Une non-campagne ? Annuaire des Collectivités Locales, 36, pp. 93-109.

Mayer, N. (2017). Les électeurs du Front National, 2012-2015. In Gougou, F., Tiberj, V. (éd.), La déconnexion électorale. Paris: Fondation Jean-Jaurès, pp. 68-77.

OpinionWay (2021). Sondage OpinionWay pour CNEWS sur les intentions de vote pour l’élection régionale dans les Hauts-de-France — Vague 3. Online.

Parodi, J.-L. (1983). Dans la logique des élections intermédiaires. Revue politique et parlementaire, 903, pp. 42-71.

Patinaux, L. (2022, 27 January). Éoliennes, la transition sans débat. Métropolitiques. Online.

Rivière, J., Colange, C., Bussi, M., Cautrès, B., Freire-Diaz, S., Jadot, A. (2012). Des contrastes électoraux intra-régionaux aux clivages intra-urbains. Éléments sur le scrutin régional de 2010 dans le Nord-Pas de Calais. Territoire en mouvement, 16, pp. 3-17.

Sauger, N. (2017). Les électeurs de droite. In Gougou, F., Tiberj, V. (eds.), La déconnexion électorale. Paris: Fondation Jean Jaurès, pp. 60-67.

Wadlow, P. (2021, 7 November). Des terrils « bleu Marine » : quelle place pour le Rassemblement national dans le bassin minier ? The Conversation.

Ward, J. K., Alleaume, C., Peretti-Watel, P. (2020). The French public’s attitudes to a future COVID-19 vaccine: The politicization of a public health issue. Social Science & Medicine, 265.

Notes

citer l'article

Tristan Haute, Marie Neihouser, Regional election in Hauts-de-France, 20-27 June 2021, Mar 2022, 40-45.

à lire dans cette issue

voir toute la revue