Regional election in Occitania, 20-27 June 2021

Julien Audemard

Researcher in political science at CNRS (Montpellier)Issue

Issue #2Auteurs

Julien Audemard

21x29,7cm - 167 pages Issue 2, March 2021 24,00€

Elections in Europe : June 2021 – November 2021

The regional elections of June 20 and 27, 2021 are the first since the merger of the former French regions in 2015. The Occitanie region, born of the merger of the former Languedoc-Roussillon and Midi-Pyrénées regions in 2015, now represents 13% of the French metropolitan territory, with its six million inhabitants spread over 13 departments, 4,454 municipalities, and 162 inter-municipalities, including the two metropolitan areas of Toulouse and Montpellier.

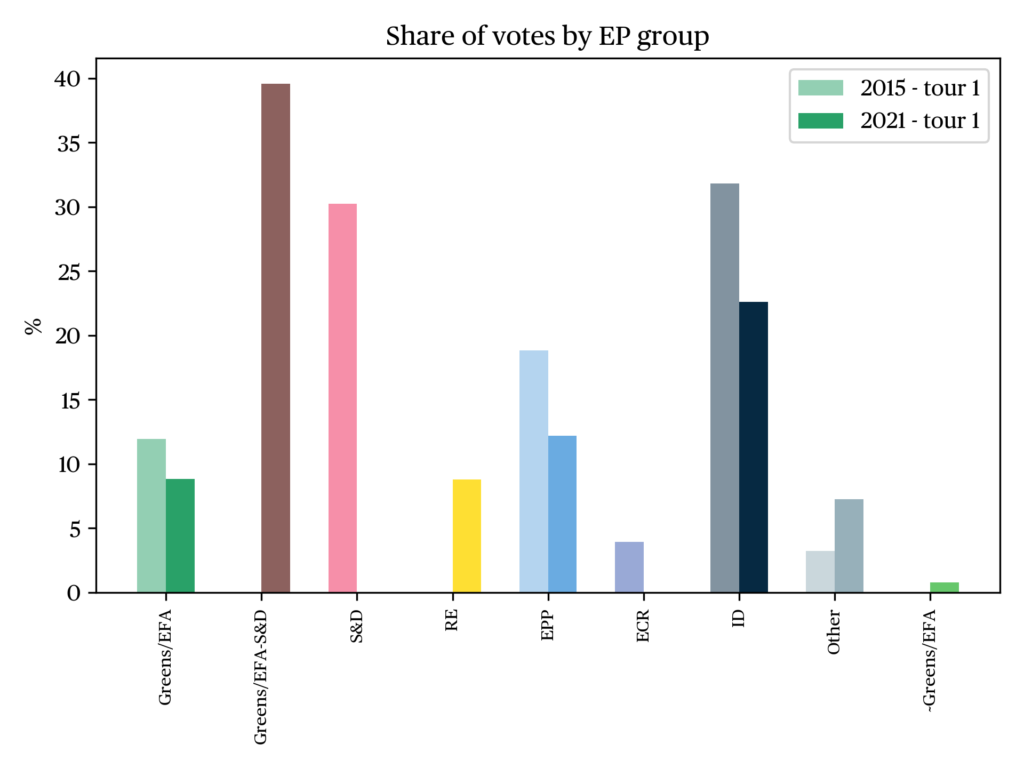

Against the backdrop of the pandemic, the abstention rate reached record levels (66.7% in the first round, 65.3% in the second). These elections were also marked by a status quo in the political balance: no region of metropolitan France swung from one camp to the other. The June 2021 elections thus confirm the territorial hegemony of two major traditional government parties, the Socialist Party (PS/S&D) and the Republicans (LR/EPP), whose dominant position at the national and municipal levels has been largely challenged for several years by the emergence of new forces – La République En Marche (LREM/Renew Europe) – or the assertion of opposition forces – La France Insoumise (LFI/The Left), Europe Écologie Les Verts (EELV/Greens/EFA) and the National Rally (RN/ID).

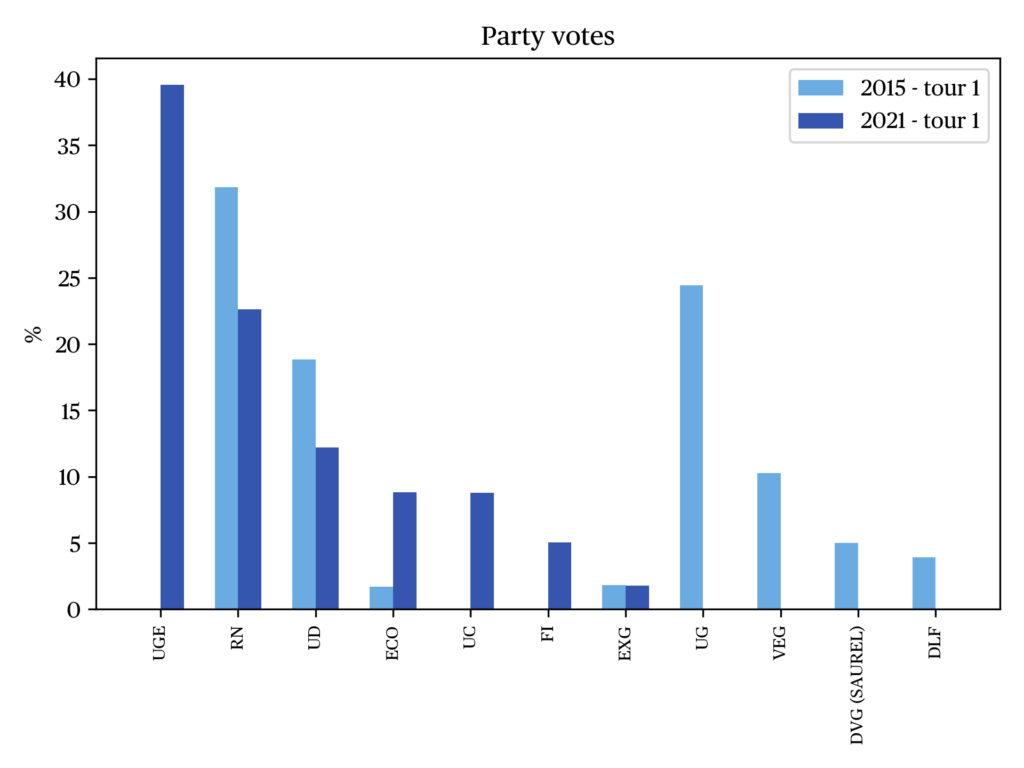

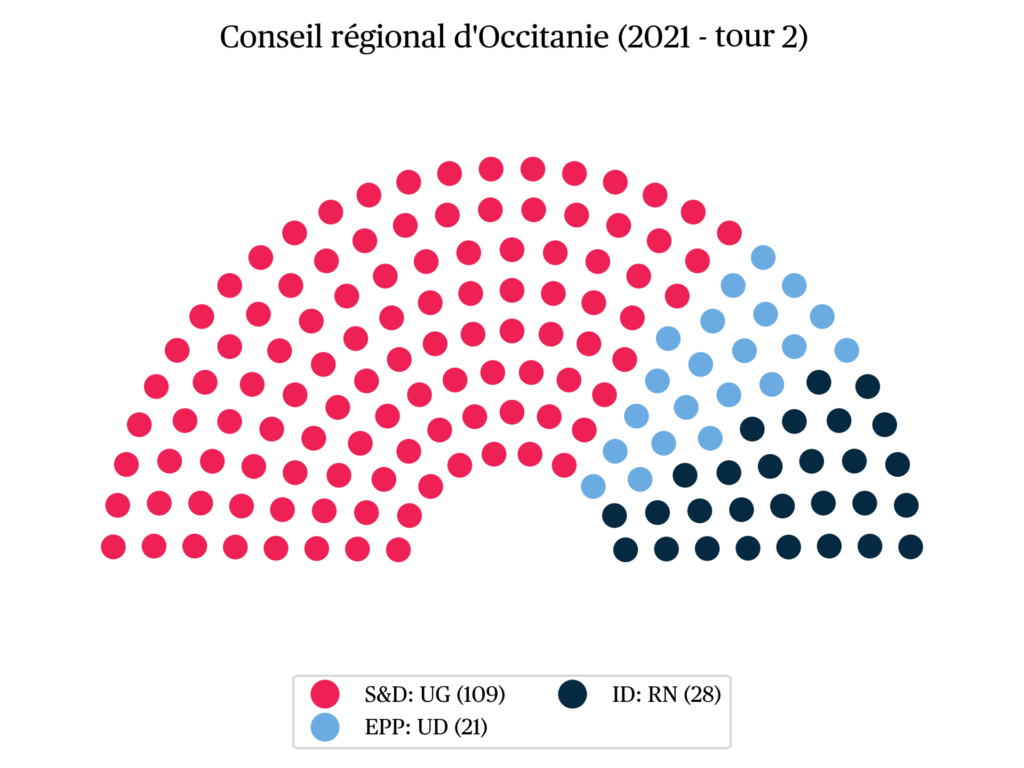

The voting in Occitania was no exception. Abstention was very high – 62.8% for the first round, 62.2% for the second – and very high compared to the previous elections in 2015 (+15 points and +17.7 points). In this context, the premium on outgoing candidates was, more than ever, relevant. The PS list led by the outgoing President of the region, Carole Delga, came out on top in the first round of the regional elections with 39.6% of the votes cast, ahead of the RN list, which finished far from the scores promised by the pre-election polls (22.6%), and the LR list (12.2%). The EELV (8.8%), LREM (8.8%) and LFI (5.1%) lists did not manage to cross the 10% threshold necessary to remain in the second round. At the end of the second round, the PS list won with a large majority (57.8%) against the RN list, whose score did not increase (24%) and the LR list (18.2%).

The left-wing majority now holds 109 seats, compared to 87 in the last legislature. Within this majority, the elected members of the Socialist group have seen their position strengthened, with 69 seats compared to 50 previously. EELV, whose list this time did not merge with the PS list in the second round, loses the 8 seats acquired in 2015 to the benefit of the communist elected representatives, who increase from 6 to 14 seats. In the opposition, while the LR and related candidates managed to hold on to their positions, the RN appeared to be the big loser in the regional elections. The LREM and their allies (3 seats in 2015) and the elected members of the far left minority (6 seats in 2015) disappeared from the Toulouse assembly landscape.

The Socialist Party, a party with reinforced hegemony

Despite a comfortable position, with a solid regional majority acquired in 2015

1

, the control of all the departmental executives of Occitania except Aveyron and Tarn-et-Garonne and the return of Montpellier

2

to the socialist fold, the traditional moderate left could have some concerns about the outcome of these new local elections for at least two reasons.

The first is related to its inability to situate itself with respect to contemporary forms of protest, whether socio-territorial, with the Yellow Vests, or socio-environmental, with the mobilizations on the theme of climate change. What was for a long time the essence of the left and, in particular in one of the poorest regions of France, the mark of its territorial hegemony, seemed to escape it. The second reason is related to its own internal problems: at the end of 2017, the union built between the two rounds of December 2015 between the PS and its allies and the group «A new world in common» which itself came from an alliance between ecologists, LFI, French Communist Party (PCF) and regionalists, broke up with the separation between LFI and the other components, the latter remaining allied with the socialist majority led by Carole Delga. The PS list approached the regional elections of 2021 by being competed, on its left, by LFI and by EELV, strong of its recent successes in the European elections of 2019 and municipal elections of 2020 for the latter.

The result of the regional elections of June 20 and 27, 2021, may therefore appear surprising. The first reason for this is undoubtedly the divisions among the left-wing opponents of the PS. Some of the ecologist forces called to vote for Carle Delga, particularly in Montpellier. The second reason is the massive abstention of the Occitan electorate. If we find, behind this large demobilization, the differences in participation traditionally observed between social categories and backgrounds (Braconnier, Coulmont & Dormagen, 2017), we note that it is very largely structured by an urban/rural divide (Tarrow, 1971).

Thus, in the first round of the regional elections, there were significant differences between Haute-Garonne (36.7%) and Hérault (33.3%), the two most populous departments in the region, and Lozère (48.4%), the least populous department, and other rural departments such as Gers (44.7%) and Lot (43.8%). More mobilized, the rural departments are also those where abstention increases the least compared to the first round of 2015. There is also an inverse relationship between the size of the municipalities and the rate of participation in the first round of these regional elections: 51.8% for municipalities with less than 500 inhabitants, 43.6% for municipalities with 500 to 1000 inhabitants, 38.9% for municipalities with 1000 to 5000 inhabitants, 35% for municipalities with 5000 to 40,000 inhabitants and 30.2% for the 13 municipalities with more than 40,000 inhabitants in the region.

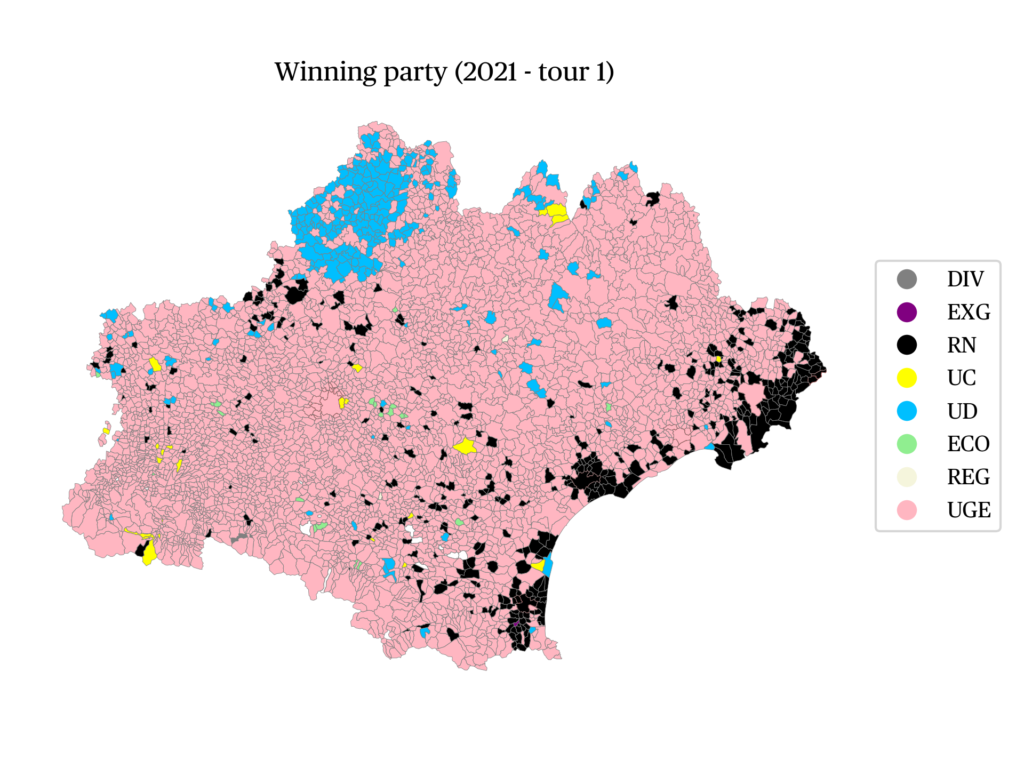

The political forces of the left, such as LFI or EELV, could only note the failure of their solitary undertakings, and the weakness of their territorial roots, which is all the more prohibitive in this context of weak mobilization of urban areas. On the other hand, the outgoing majority was able to rely on its roots to clearly amplify all the polling forecasts. The Delga vote is relatively homogeneous throughout the territory, with new areas of strength, quite unusual, formerly uncontested bastions of the right (Lozère). Only a specific area and very little mobilized, the vast Languedoc coastline, remains one of its main areas of weakness.

On the right, the RN, a loser’s hegemony

Convinced of its dominant position on the right in the last European elections, the RN had at least the hope of repeating the feat in these regional elections, in a region where, with its allies, it had succeeded in retaining the cities of Beaucaire and Béziers, acquired in 2014, and had won, in addition to Moissac, its first French municipality of more than 100,000 inhabitants with Perpignan. Without it being possible to speak of a real anchoring, the party could therefore rely on these victories, as well as on a contingent of 36 regional elected officials spread across all departments.

The regional elections in Occitania have allowed, as elsewhere, to highlight the structural weaknesses of the RN. In decline compared to 2015 in all departments, its areas of strength are even more concentrated on the Mediterranean coast, where the fall in its scores is more contained than elsewhere. The situation of the RN in these regional elections once again calls into question the old idea of a positive link between the scores of the far right party and abstention. It is not absurd to think that the RN suffers, in a context of very low mobilization, from the characteristics of its electorate – urban and peri-urban, from the working classes and the small middle class. Thus, with rare exceptions, the RN’s scores in the first round are systematically down compared to 2015 in municipalities with more than 1000 inhabitants. While it retains a hegemonic position on the right where it is ahead of the LR list everywhere except in three departments (Aveyron, Lot and Lozère), it does not even ensure that it maintains the positions acquired in 2015: the RN thus sees the number of its regional elected representatives fall to 28.

The low number of RN elected officials in communal and departmental executives may also explain the party’s inability to mobilize a larger share of its electoral base. Conversely, the anchoring of the LR list guarantees that it will initially remain in the second round of the election and then achieve a score fairly close to that of 2015, allowing it to retain 21 seats in the regional assembly.

Allied with the Mouvement Démocrate (MoDem) in the 2015 election, LR had only been able to obtain 21.3% of the votes in the second round, far behind the 33.9% of the Front National (FN), now the leading force on the right in the region. Prior to the 2021 election, the alliance between the right and the center had nevertheless won Toulouse in the 2014 municipal elections, and then retained it in 2020. However, unlike in 2015, the right and the governmental center this time made separate lists, LR allied with the Union of Democrats and Independents (UDI) and LREM with MoDem.

If the LR list shows a significant decline in 2021 compared to the first round of 2015 in all the departments of the region, and in particular in the departments where the left-wing vote is best established (Ariège, Haute-Garonne, Hautes-Pyrénées and Tarn), it is clearly progressing in the Lot, where its score in 2021 (34.8%) is 58% higher than in 2015 (22%), undoubtedly due to a «local friendship effect» (Audemard & Gouard, 2020) beneficial to the head of the regional list Aurélien Pradié, «the child of the country». Unsurprisingly, the absence of an alliance proved to be a failure for the presidential party, which does not benefit from such an anchoring. The list led by Vincent Terrail-Novès could not make it to the second round.

Parties and territories: a deceptive consecration

Presented as modern forms of organization on the way to supplanting the traditional parties and their rigid, territorialized structure, the movements have had an even harder time of it in this electoral sequence than their territorial establishment has been rehabilitated. Like Europe Écologie Les Verts, La République En Marche counted neither directly (elimination in the first round) nor indirectly (absence of alliance) at the regional level. As for France Insoumise, it also suffered a defeat due to an underestimation, on its part, of the inter-partisan constraints of the political game. In its case, however, another constraint, a sociological one, has affected it in the same way as the Rassemblement National: the demobilization of its popular electorate. Instead of this resistible rise of movements against the territories, it is indeed the latter that have played a strong role.

However, it would be inappropriate to see these results as a consecration. The disaffection of a large majority of the electorate for the ballot box has once again been confirmed. The democratic impasse facing the parties remains — more than ever — on their programmatic and strategic agenda. The reason for this is that, with the control of the outgoing executives, they were the least weakened by the massive abstention movement, accentuated by the pandemic context, from which these local elections did not escape.

Literature

Audemard, J. & Gouard, D. (2020). Friends, neighbors, and sponsors in the 2016 French primary election. Revisiting a classical hypothesis from aggregated-level data. Political Geography, 83.

Braconnier, C., Coulmont, B. & Dormagen, J-Y. (2017). Toujours pas de chrysanthèmes pour les variables lourdes de la participation électorale : chute de la participation et augmentation des inégalités électorales au printemps 2017. Revue française de science politique, 67(6), pp. 1023–1040.

Négrier, E. (2021). L’analyse électorale à l’épreuve de la recomposition politique. Le cas des élections municipales en Occitanie et à Montpellier. Pôle Sud, 54, pp. 13–30.

Négrier, E., Volle, J-P. & Coursière, S. (2016). Nouveaux territoires et héritages politiques. Les élections départementales et régionales de 2015 en Languedoc-Roussillon/Midi-Pyrénées. Pôle Sud, 44, pp. 111–132.

Tarrow, S. (1971). The Urban-Rural Cleavage in Political Involvement: The Case of France. The American Political Science Review, 65(2), pp. 341–357

Notes

citer l'article

Julien Audemard, Regional election in Occitania, 20-27 June 2021, Mar 2022, 52-55.

à lire dans cette issue

voir toute la revue