China’s Uneven Regional Energy Investments

Issue

Issue #1Auteurs

Han Chen , Cecilia Springer

21x29,7cm - 153 pages Issue #1, September 2021

China’s Ecological Power: Analysis, Critiques, and Perspectives

In the lead-up to the first Belt and Road forum in May 2017, China published its “Guidance on Promoting Green Belt and Road,” “Belt and Road Ecological and Environmental Cooperation Plan,” and “Vision and Actions on Energy Cooperation in Jointly Building Silk Road Economic Belt and 21st-Century Maritime Silk Road”, emphasizing that its investment projects will be used to promote the Paris Agreement and 2030 Sustainable Development Goals and are motivated by the need to “share the ecological civilization philosophy and achieve sustainable development.”

Despite official policy, China’s Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) has come under continued criticism for promoting dependence on fossil fuels in developing nations and investing in environmentally damaging infrastructure projects. The BRI is heavily invested in global energy infrastructure. Within the energy sector, power generation is the largest destination for Chinese development finance, and of that, coal-fired power generation makes up the largest share 1 . Fossil fuel-based power generation produces CO2 emissions that contribute to climate change, as well as local air pollution that damages the health of communities near a given power plant.

The regional distribution of power plants with Chinese involvement is highly uneven, and the share of different fuel types also varies by region. Host country preferences play a major role in determining the types of electric power generation that are developed with Chinese partners, demonstrating a complex network of “supply push” and “demand pull” factors that ultimately determine fuel choice and technology quality for a given project 2 .

In seeking to understand regional patterns in Chinese involvement with the global electric power generation sector, we first clarify types of Chinese involvement. Prior research has heavily focused on overseas development finance disbursed by China’s state policy banks, the China Development Bank and the China Export-Import Bank. However, since a peak in 2016, Chinese overseas development finance for the energy sector has decreased over time 3 . In order to capture changing trends in how Chinese finance flows overseas, we also include data on China’s foreign direct investment (FDI) in the power generation sector. We also track Chinese involvement via construction companies, such as those with Engineering, Procurement, and Construction (EPC) contracting arrangements, a growing channel for Chinese companies going overseas 4 .

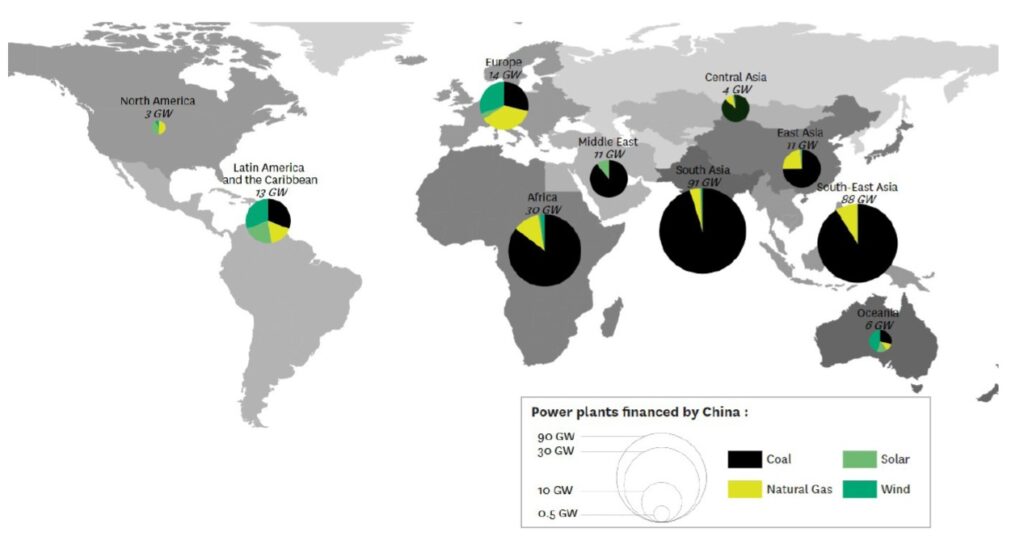

Assembling this novel dataset, we then explore regional patterns in Chinese involvement, as well as regional distribution of power generation capacity for different types of fuels receiving Chinese finance and investment. We focus on the patterns between fossil fuel generation and renewable energy, in the forms of coal and natural gas for fossil generation, and wind and solar for renewable energy. Our final dataset includes 1,027 coal, gas, wind, and solar plants representing 272 GW of capacity, including operational and planned plants between 2000 and 2033 (Figure 5). In this dataset, all plants involving a chinese EPC arrangement are coal plants. Given that fossil fuel generation is inherently carbon intensive, while wind and solar are low carbon sources of electricity, we focus our discussion on case studies and policy recommendations that affect the incentives for Chinese developers of both categories of energy. We conclude with policy recommendations for China to achieve its stated aim of a green BRI that aligns with the Paris Agreement and the Sustainable Development Goals of China.

Main Findings

Shifting Trends in How China is Involved in Overseas Power Generation

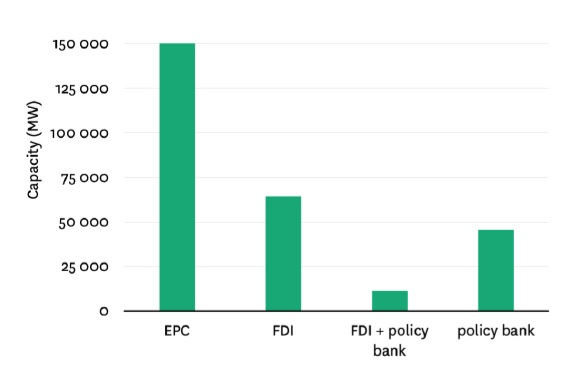

Our dataset shows that, from 2000, there are a significant number of Chinese construction contractors going overseas to build coal plants, not necessarily financed by Chinese policy banks or FDI. In the coal sector alone, the capacity represented by these arrangements dwarfs Chinese policy bank finance and FDI for coal, gas, solar, and wind combined (Figure 1). Our dataset tracks construction arrangements without associated policy bank finance or FDI, although the plants with identified Chinese policy bank finance or FDI may also have Chinese construction contractors (that is, the capacity associated with Chinese construction companies should be seen as a minimum).

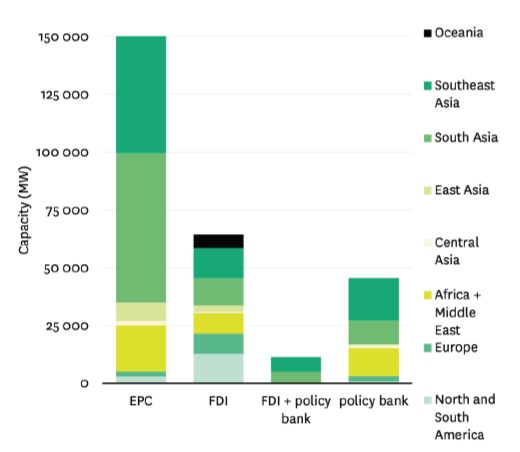

Breaking this down by region, we can see that policy bank finance for power generation and construction arrangements for coal are dominant in South and Southeast Asia, while Chinese FDI is distributed more evenly across regions.

Figure 1 • Global Power Plants with Different Types of Chinese Involvement

It is interesting to note the outsize role that India represents in terms of Chinese construction arrangements for coal plants without associated development finance or FDI. We found a total of 150 GW of global coal capacity with Chinese construction contractors; 49 GW of this, or 33% of the total, was in India alone. This likely reflects the complicated relationship between India and China. The Indian government imposed import duties on power equipment in 2012, reducing Chinese participation in the coal power sector in India 5 . However, it is clear that Chinese construction contractors have a strong presence in India’s coal plant development market.

Many projects with Chinese involvement face significant, even permanent delays, especially coal plants in countries with looming overcapacity issues 6 . Although there is a significant amount of power generation capacity in Africa with Chinese involvement, looking at specific plants, we note that some of this capacity is represented by plants that are unlikely to ever enter operation, following years of pushback from civil society. Our dataset includes the Lamu plant in Kenya (3 coal-fired generating units of 350 MW each) and the Hamrawein plant in Egypt (6 coal-fired generating units of 660 MW each), both of which had planned to use Chinese contractors. The Lamu project faced significant legal challenges and opposition from local Kenyan activists 7 . The Hamrawein project was cancelled in 2020 as Egypt’s electricity authority opted to focus on renewable energy 8 .

Figure 2 • Chinese Overseas Power Plant Involvement Type by Region

Regional Disparities by Fuel Type

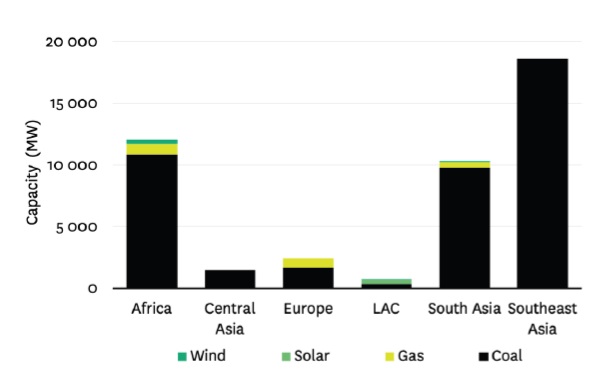

Looking at the regional variation in type of generation supported by different kinds of Chinese finance, we find that China’s policy banks have almost entirely supported coal projects abroad, exclusively so in Central and South Asia (Figure 3) over the time period covered in our dataset, 2000-2033. Among a wider range of energy types not included in this analysis, it is known that hydropower follows coal as the second largest source of global capacity receiving Chinese policy bank finance and FDI. By looking only at coal, gas, wind, and solar, our analysis shows just how stark China’s focus on coal has been, compared to wind and solar, for policy bank finance.

China’s foreign direct investment has favored investments in gas, with a majority of capacity receiving Chinese FDI in Africa, East Asia, and Southeast Asia represented by significant capacities of gas plants (Figure 3).

Europe has received policy bank finance exclusively for coal and gas, while Chinese FDI going to Europe is split between natural gas plants and wind generation, with a small amount of solar. We find that the United Kingdom is the predominant destination for both Chinese FDI within the European region, representing 48% of FDI capacity in Europe.

Figure 3 • Regional fuel breakdown for chinese policy bank finance

Our finding that a significant amount of Chinese FDI goes towards natural gas power represents a major step towards understanding the broader fossil fuel portfolio of China’s overseas activity. Prior research and advocacy has heavily focused on Chinese involvement with global coal-fired power plants. This represents a future area for research, especially the emissions impacts of Chinese gas FDI.

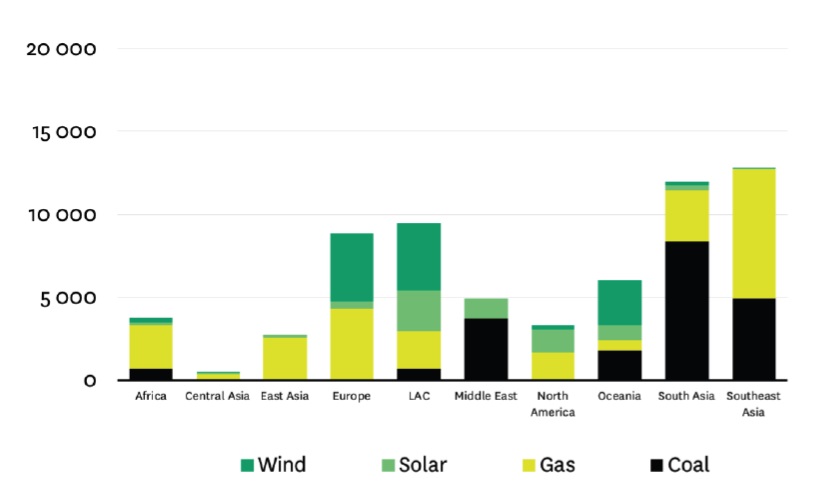

Interestingly, the portfolio of Chinese overseas finance for power generation does not appear to have become cleaner over time. Following major commitments to low-carbon emissions trajectories such as the Paris Agreement in late 2015, the overall composition of global power plants receiving Chinese finance has not significantly changed. Although policy bank finance is generally on the decline, in recent years it continues to be essentially entirely for coal-fired power generation. Focusing on plants that came into operation between 2000 and 2021, we see that annual FDI has oscillated between renewable-heavy and fossil-heavy projects over the past few years (Figure 4).

Figure 4 • Regional fuel breakdown for china’s Foreign Direct investment

Regional Policy Barriers to China’s Overseas Renewable Energy Investment

Given the trends we have identified of significant Chinese FDI into overseas natural gas plants and no evidence of transition towards renewable energy in recent years, in this section, we explore policy barriers to promotion of renewable energy through Chinese overseas development finance, FDI, and construction arrangements. With China’s recent announcement of a commitment to achieving carbon neutrality by 2060, there is an increasing discrepancy between the types of power generation China is promoting domestically compared to overseas. Will Chinese companies expand their dominant position in domestic solar and wind installations to more projects overseas?

In terms of the other countries within the Belt and Road Initiative, research suggests that there have been strong preferences for lowest-cost electric power generation, which often translates into local policymakers’ preferences for coal power plant construction 9 . However, as more nations announce decarbonization commitments as part of the Paris Agreement, it is likely that there will be greater interest in increasing renewable energy’s role in more countries. However, many barriers still exist to increasing investment in global renewable energy. These barriers are both general to renewable energy investment, but must be specifically addressed with regards to the Chinese financing context.

Renewable energy is increasingly economically viable on a stand-alone basis. However, many developing countries face underdeveloped capital markets to finance renewable energy infrastructure. Thus, attracting and accessing more foreign capital is necessary to finance projects. This requires a comprehensive enabling environment on the part of the host country, including changes in policy, financing, and planning.

While there have been some recent advances in innovative partnerships between philanthropy, donor governments, local governments and businesses, such efforts have not been scaled up to the level needed to help countries meet their Paris Agreement targets. Countries can create a more attractive investment environment for renewables by re-directing fossil fuel subsidies towards renewables. The broader grid system must also be considered. In many countries, outdated or underdeveloped grid infrastructure is a limiting factor for renewables integration (IRENA 2018), leading to high risk aversion from grid companies and conventional lenders. For example, in rural areas with low electricity access, renewable energy buildout may need to be relatively distributed and small-scale, leading to comparatively higher transaction costs and less commercial appeal 10 .

Figure 5 • Author’s dataset: Power plants financed by china, under construction or in operations (2000-2033)

Chinese financiers and construction companies can play a role in facilitating the pipeline for renewable energy overseas. As China increases its focus on a green Belt and Road Initiative, there may be more opportunities for host country stakeholders active in sustainability initiatives to connect with interested stakeholders or investors in China. China has a major comparative advantage not only in manufacturing wind and solar generating technology, but also related technology that can support the integration of renewables, like ultra-high-voltage transmission lines and energy storage. However, there has yet to be a systematic effort from within China to direct overseas energy investments towards renewables or to facilitate Chinese renewable energy companies in going overseas. A recent report sponsored by China’s Ministry for Ecology and Environment introduced a “traffic light” system to grade investments on their sustainability (BRI IGDC 2020), but such a rating system has yet to be incorporated into decision-making. A major area of opportunity is facilitating the transfer of Chinese technical capacity through capacity building initiatives that can help host countries with energy planning, renewables integration, modern grid design and piloting. Chinese companies that are closely involved in the region, either as construction contractors or as shareholders in local grid companies and generation projects, have very valuable experience in clean energy and can be a key resource for renewable energy transition.

Given that our data has revealed a major concentration of fossil fuel power generation with Chinese finance and investment in Asia, we examine three subregions within Asia to assess the state of renewable energy and specific policy barriers.

Central Asia 11

The region has rich renewable resource potential, including wind resources in Kazakhstan and solar in Uzbekistan. However, the aging power generation infrastructure in the region needs modernization 12 . Moreover, Central Asia is 42-73 percent rural and many areas have yet to be electrified 13 . Investment in renewables has been low, with most projects promoted by multilateral development banks such as the European Bank for Reconstruction and Development, the Asia Development Bank, and the World Bank, while private sector investors have only played a small role thus far.

Given Central Asia’s prominence in the Belt and Road Initiative (the BRI was officially launched during Xi Jinping’s visit to Kazakhstan in 2013), there is room for more Chinese engagement in renewable energy, especially through FDI. Central Asian governments need to articulate demand for overseas investment for renewables and provide quality information about the region to attract investors. Countries can educate the public on the importance of renewables through issue linkages, such as highlighting the impact that the smog generated by coal-fired power plants in Bishkek (Kyrgyzstan) has on public health and how renewables can mitigate that.

South Asia 14

Many South Asian countries have untapped renewable energy resource potential, but a major investment gap. Countries in the region are currently facing large capacity payment issues for carbon-intensive power plants, meaning that system operators still need to pay power plants even when the plants are idle. This is a growing concern in Pakistan and Bangladesh, where power planning forecasts indicate there may be excess capacity in the years ahead if current planned investments, many of them with Chinese partners, are implemented. Pakistan has 10GW of coal-fired power generation capacity planned, but also has a 30 percent renewables target for 2030. Chinese investment in Pakistan has frequently clustered in special economic zones or industrial corridors, highlighting the need for more diverse energy investments both in terms of type of energy, location, and the necessary transmission and distribution infrastructure to facilitate energy access. The Bangladesh government received much criticism for a coal-heavy power development plan in 2020, and has since scaled back. In 2018, idle power plants in Bangladesh received over $1 billion in capacity payments, a significant loss of government revenue 15 . Even given these losses, official future energy scenarios in Bangladesh still heavily feature coal, natural gas, and LNG imports 16 .

India remains a world leader in solar installation and bringing down the levelized cost of electricity for solar energy. India may propose a World Solar Bank to finance investments in solar energy, which will likely benefit neighboring countries seeking to scale up solar energy and move away from coal. However, there are competing influences from China and India within other South Asian countries, and geopolitical tensions may obstruct cooperation on renewable energy.

Southeast Asia 17

The current status of renewables deployment is highly uneven between countries in Southeast Asia. Some countries are still facing electricity access issues, namely Myanmar and Cambodia. However, other countries have many “shovel ready” projects in renewable energy looking for financing. Given grid interconnections between some countries and China, careful planning of renewable energy expansion can help address issues with access and reliability in southern China, Laos, and Myanmar. Despite proximity to China, Chinese renewable energy developers have yet to make major headway into Southeast Asia.

Some Southeast Asian countries are emerging as regional energy developers, especially Vietnam and Thailand. Vietnam recently extended its feed-in-tariff by two years, and Malaysia announced plans for a large-scale solar program which will generate thousands of jobs. Vietnam’s impressive growth in renewables is a success story, including the move from feed-in-tariffs to auctions, but the risks of over-building gas infrastructure will need to be addressed as well. Given China’s involvement in the full range of countries in Southeast Asia, there are opportunities for regional collaboration on development of renewable energy projects that take advantage of positive experiences both from China and Vietnam, for example.

Discussion

Given rapid global expansion in renewable energy, it is evident that renewable energy investments are profitable, economically viable, and critical to achieving climate goals. China can facilitate this continued global expansion if it aligns its domestic focus on carbon neutrality and green development with its overseas activities in BRI countries. Many BRI countries are developing countries that can use Chinese assistance to develop modern, clean energy systems with less environmental impact. Our data has shown that despite a major focus on fossil fuels, especially in certain regions, China is to some extent already facilitating renewable energy overseas in the form of development finance and FDI. Although not included in our study, Chinese construction contractors and equipment exporters are also playing a role in overseas renewable energy development.

Positive Case Studies

Given the general and regional barriers discussed above, we sought to identify positive case studies of Chinese involvement in overseas renewable energy in order to glean policy lessons for implementation and scaling. Some notable examples of Chinese involvement in overseas renewables projects include:

- The Sweihan Photovoltaic Project, a 1.17 GW project jointly developed by China’s JinkoSolar and Japan’s Marubeni in Abu Dhabi, UAE, which includes a 25 year power purchase agreement (PPA) with the Abu Dhabi Water and Electricity Authority;

- Sinomach and General Electric’s cooperation on a 100 MW wind power demonstration project in Kipeto, Kenya;

- Chinese financing and construction of the 300 MW Cauchari Solar PV plant in Argentina, expanding to 500 MW over time. The $390 million project is primarily being funded by the Export-Import Bank of China and Shanghai Power Construction is leading the construction using Chinese company Talesun’s solar panels;

- The acquisition of an 80% stake in the German Meerwind offshore wind farm by the Three Gorges Group;

- The Silk Road Fund’s purchase of shares in a Shanghai Electric and Saudi ACWA concentrated solar power project;

- PowerChina participated in the Dawood Wind Farm project in Pakistan as the developer and EPC.

China’s renewable investments abroad are not limited to BRI countries. Chinese financing for specific renewable energy projects has occurred in Australia, the United States, and the United Kingdom, for example. Chinese financiers may be willing to work with partners in such countries on renewable energy due to relatively developed energy markets that provide greater policy certainty for solar and wind development, either through incentives such as renewable portfolio standards, tax cuts, or other policy measures. In contrast, investment in renewables has been lower in countries that do not offer a stable policy environment for renewables deployment. While the technical renewable energy potential in regions such as Southeast Asia is very high, policy incentives for Chinese engagement in the region are still lacking, as discussed above.

In terms of solar photovoltaics specifically, as the top manufacturer of solar PV products, China has exported these products to an increasingly diverse array of countries around the world in response to growing demand for low-cost, low-carbon energy 18 . Private Chinese companies like Jinko Solar, Canadian Solar, LONGi, Trina Solar, JA Solar and more have established solar cell and module production bases in countries like Vietnam, Malaysia, Thailand, Indonesia, and Germany, forming a supply chain and market network of high-end solar equipment connecting China with foreign countries. In going global, these companies have lowered global solar prices through their highly efficient vertical supply chains. Chinese solar companies provide FDI, construction arrangements, and equipment sales and services.

In terms of wind, Chinese power companies including the China Three Gorges Corporation, the China General Nuclear Power Group, the China Energy Investment Company, Goldwind, Envision Energy, Ming Yang Smart Energy, etc. have participated in the investment and construction of wind projects in the UK, Germany, Australia, and others.

Policy Recommendations

We focus our policy recommendations on three key groups: Chinese institutions, host countries, and global partner institutions.

Chinese Institutions

At present, BRI deals between China and host governments are often led by Chinese State-Owned Enterprises (SOEs), with large projects requiring approval from China’s National Development and Reform Commission and/or other government agencies. As such, project recommendations may sometimes be driven more by China’s domestic supply side considerations for SOEs (who are more experienced in fossil-fuel related infrastructure), and less motivated by what would be most sustainable for the host country. China has already signalled high-level political commitment to green the BRI in principle, though implementation remains a challenge. There are already initiatives such as BRI Low Carbon Cities, tools like the China Green Finance Committee’s calculator for environmental impacts, the Committee’s innovative green finance products to lower the cost of renewables, and the green project investment database under the Green Investment Principles for the Belt and Road, which can help potential green BRI projects access global public sector and private sector capital.

Further measures that could have significant impact include the following:

- China can share its expertise in innovative financial products: sustainable bonds, green/ESG bonds, crisis recovery facilities.

- As government funds are limited, including for China, Chinese companies can increase their engagement with multilateral development banks and financial institutions such as EBRD, African development bank (ADB) and Asiatic infrastructure investment bank (AIIB) to pool more capital for renewable energy projects.

- China could promote and contribute to more integrated solutions for energy infrastructure in host countries, including grid infrastructure and capacity building that are choke points for the broader deployment of renewable energy.

- Chinese civil society organizations can connect with those in developing countries for greater South-South cooperation and exchange on promoting renewable energy.

- China can consider encouraging its companies to enhance environmental and climate considerations for project investments overseas, e.g. through the “traffic light system” discussed earlier.

Host Countries

To green the BRI, host countries must articulate demand for more renewable energy investments, and less fossil energy investments. Countries should increase collaboration on renewable energy investment with Chinese SOEs and private companies that are contractors, project developers, and financiers.

Many challenges are still ongoing in host countries, including political challenges of reforming fossil fuel subsidies and introducing carbon pricing, finding transition solutions for countries dependent on exporting fossil fuels, the need to take into account worker transition, and the need to diversify local economic models.

Further measures that could have significant impact include the following:

- Countries must address the conservatism in behavior of relevant ministries and procurement officers. These stakeholders can benefit from learning about the rapidly changing energy landscape so they are less likely to prefer fossil fuel infrastructure technologies that could pose long-term stranded asset risks or burdens for government budgets.

- More government guarantees for renewable energy projects can put them on a more level playing field.

- A growing market for green investments and bonds can attract more private sector capital.

- One potential idea is to develop a green coalition of BRI nations, with a shared investment framework and higher environmental, climate and health standards. A green coalition could link regulators, utilities, financiers, project developers and others, standardizing procurement policies. Many resources exist, but countries should improve information sharing via existing channels (e.g. ASEAN, Southeast Asia Energy Transition Partnership). Having Green BRI “pilot countries” will allow learning on scaling green investment.

- Countries can develop enabling conditions for sustainable energy, such as stable regulatory environments for renewables with clear operational guidance, mechanisms like PPAs, and improve the conversation between regulators, investors and utilities.

- Adopt a long term carbon neutrality goal, as China and several other countries have done, to drive policy and finance across all parts of the economy.

- Conducting more public awareness programs on the benefits of renewables and of reducing pollution or smog.

Global Partner Institutions

Global institutions and partners can help enable Chinese institutions and host countries to develop renewable energy through these measures:

- Global institutions such as development banks, intergovernmental institutions and coalitions can encourage the formulation of stronger environmental and social governance standards around BRI projects – articulating the need for these policies with key Chinese institutions such as the National Development and Reform Commission, Ministry of Commerce, and the State-owned Assets Supervision and Administration Commission, and with ministries in each BRI country.

- Global institutions should encourage China to implement green investments with clear targets and timelines.

- Countries and partner institutions can support more rapid deployment of green projects by establishing a Green Guarantee Fund to reduce project risk costs, such as through participation in the Green Investment Principles for the Belt and Road, which has already brought together 37 global institutions with total assets of over 41 trillion USD.

- Institutions can support the development of green BRI pilot countries, facilitate dialogues and exchanges on standardization of project development and procurement, help crowd in private finance, provide blended financing and other options.

- Institutions can accelerate South-South peer-to-peer awareness raising and learning, investment, and development by promoting regional hubs of excellence.

- The private sector and multilateral financial institutions can engage more with Chinese companies that are leaders in renewable energy.

- Multilateral Development Banks could help bring initial capital support to finance higher risk clean project pilots, as well as financing development missions such as education and awareness enhancement.

Conclusion

Renewables are already competitive with coal plants in many countries in Asia such as China, South Korea, Thailand, Vietnam 19 , and more and more fossil fuel investments may become “stranded assets,” which are as disastrous financially for investors as they are environmentally for local communities. Our data shows that, from 2000, China has provided development finance weighted towards coal, and FDI weighted towards natural gas, as well as significant construction arrangements for global coal-fired power plants, and that renewable energy has not superseded fossil investments in recent years.

Fortunately, the efforts to green the Belt and Road can help to drive financial flows towards more sustainable renewable energy resources. This paper has highlighted the current policy barriers to Chinese finance for renewable energy around the world, and identified policy recommendations to overcome these barriers.

In early 2021, the Chinese embassy in Bangladesh indicated via a letter that the Chinese government would not finance a coal plant in Bangladesh as “the Chinese side shall no longer consider projects with high pollution and high energy consumption, such as coal mining, coal-fired power stations, etc.” 20 . During the annual meeting of China’s National People’s Congress in 2021, a researcher from the State Council indicated that China is no longer financing coal power projects and focusing on solar, wind and nuclear projects to promote a green Belt and Road Initiative 21 . A shift away from coal is a positive development in terms of global emissions. Further research will be required to verify if the end of coal support from China will cover only policy bank financing, or whether this restriction will also extend to other areas such as construction arrangements and FDI.

Method: Data Collection

We assembled a novel dataset on global power generation projects spanning Chinese involvement via development finance, foreign direct investment, and construction arrangements. We selected only power plants with coal, gas, wind, and solar as their primary fuel, and excluded canceled and retired plants from 2000 to 2033. We also only examine plants outside of China.

For power plants with Chinese development finance from policy banks and foreign direct investment, we used the Boston University China’s Global Power (CGP) database 22 , which spans power plants commissioned and planned between the years 2000 and 2033. Plants with years of commission from 2021 and beyond are under planning or construction, while plants from 2020 and prior have been verified to be in operation.

To identify construction arrangements, we used the Platts World Electric Power Plants (WEPP) database to identify the country of origin for the architecture and engineering or construction company involved with each individual plant. For EPC arrangements, we only investigated coal plants due to the relative completeness of data on this type of power plant. We began with a list of known Chinese construction companies, and matched this list to the companies noted in the WEPP data. It should be noted that these plants with Chinese construction contractors are mutually exclusive from the CGP dataset; that is, these represent power plants without identifiable Chinese finance or investment, yet that still have Chinese construction contractors. There are likely a significant number of global power plants that have both Chinese finance or investment and a Chinese construction contractor. Given significant missing data on engineering and construction companies at the plant level, our estimates should be seen as a bare minimum for Chinese construction arrangements for global coal plants.

The final dataset includes 1,027 coal, gas, wind, and solar plants representing 272 GW of capacity, including operational and planned plants between 2000 and 2033 (Figure 5).

Notes

- K.P. Gallagher et al., “China’s Global Power Database”, Global Development Policy Center, Boston University, 2019 ; M. Muñoz Cabré et al., “Expanding Renewable Energy for Access and Development: the Role of Development Finance Institutions in Southern Africa”, Boston University, Global Development Policy Center, 2020 ; Z. Li et al., “China’s global power: Estimating Chinese foreign direct investment in the electric power sector”, Energy Policy 136, 2020.

- B. Kong, & P. K. Gallagher, “Inadequate demand and reluctant supply: The limits of Chinese official development finance for foreign renewable power”, Energy Research & Social Science 71, 2021.

- X. Ma, K. Gallagher, S. Chen, “China’s Global Energy Finance in the Era of Covid-19”, Boston University Global Development Policy Center. Global China Initiative Policy Brief, 2021.

- H. Zhang, “The Aid-Contracting Nexus: The Role of the International Contracting Industry in China’s Overseas Development Engagements”. China Perspectives 17–27, 2020. For a full discussion of our methods, see the last section of this article.

- Peng, “ China’s Involvement in Coal-Fired Power Projects Along the Belt and Road ”, Gei China, 2017.

- S. Nicholas, “Shelving of huge BRI coal plant highlights overcapacity risk in Pakistan and Bangladesh”, China Dialogue, 2020.

- Shi, “Kenyan Coal Project shows why Chinese investors need to take environmental risks seriously”, China Dialogue, 2021.

- Farag, “Egypt postpones $4.4 billion, 6GW coal plant, pushes renewables instead”, Institute for Energy Economics and Financial Analysis, April 2020.

- E. Downs, “ The China-Pakistan Economic Corridor Power Projects: Insights into Environmental and Debt Sustainability ”, Columbia University Center on Global Energy Policy, 2019.

- M. Muñoz Cabré et al., “Expanding Renewable Energy for Access and Development: the Role of Development Finance Institutions in Southern Africa”, Boston University, Global Development Policy Center, 2020.

- Includes Mongolia, Kazakhstan, Tajikistan and Uzbekistan in the dataset.

- Kim, “In Central Asia, a Soviet-era electricity network could power future energy sharing”, 2020.

- World Bank, “Rural population (% of total population) – Europe & Central Asia”, 2021.

- Includes India, Bangladesh, Sri Lanka, Nepal and Pakistan in the dataset.

- S. Nicholas, “Shelving of huge BRI coal plant highlights overcapacity risk in Pakistan and Bangladesh”. China Dialogue, 2020.

- A. Gulagi, et al., “Current energy policies and possible transition scenarios adopting renewable energy: A case study for Bangladesh”, Renewable Energy 155, 2020.

- Includes Cambodia, Indonesia, Laos, Malaysia, Myanmar, Papua New Guinea, Philippines, Singapore, Thailand and Vietnam in the dataset.

- M. M. Jackson, et al., “A green expansion: China’s role in the global deployment and transfer of solar photovoltaic technology”, Energy for Sustainable Development 60, 2021.

- Wood Mackenzie, “Renewables in most of Asia Pacific to be cheaper than coal power by 2030”, 2020.

- China Economic Review, “China turns its back on Bangladesh BRI coal projects”, 2021.

- Xinhua News Agency,. “Interpretation of the Two Sessions: The “Belt and Road” construction will maintain its upward momentum in 2021”, 2021.

- K. Gallagher et al., “China’s Global Power Database”, Global Development Policy Center, Boston University, 2019 ; K. Gallagher et al., “China’s Global Energy Finance”, Global Development Policy Center, Boston University, 2019.

citer l'article

Han Chen, Cecilia Springer, China’s Uneven Regional Energy Investments, Sep 2021, 98-107.

à lire dans cette issue

voir toute la revue