The EU and China: Climate and Trade Increasingly Intertwined

Susanne Dröge

Senior Researcher in the Global Issues Programme of the German Institute for International and Security Affairs (SWP)Issue

Issue #1Auteurs

Susanne Dröge

21x29,7cm - 153 pages Issue #1, September 2021

China’s Ecological Power: Analysis, Critiques, and Perspectives

The EU and China – different ambitions and actions on climate

The interlinkages between trade and climate change have risen to the top of the international negotiations on climate cooperation. This effect is partly caused by the Green Deal of the European Commission, by the revival of international climate and trade talks after the US elections 2020, and by the increasing knowledge and data that show that trade flows can both undermine and support climate action. Trade flows cause transport emissions and they help to disseminate emission-intensive goods and practises, but trade flows can also help to speed up deployment of climate-friendly technologies.

In Europe, climate protection to an increasing degree becomes part of political projects like industrial strategies, social justice and post Pandemic recovery 1 . The EU also aims at greening financial market regulation and government procurement rules as well as a growth stimulus. The European Union has decided to reduce its GHG-Emission by 55 percent in 2030 and to become climate-neutral until 2050.

China, on the contrary, has no such concrete ambitions in place yet. China’s latest five-year plan does not show any intensification of climate protection activities. Rather, it repeats the level of ambition from the last five-year plan (minus 18% carbon intensity).

As China is the most important trade partner of the EU (16% in 2020 2 ), it matters for both parties, how strict or lax they implement constraints on fossil fuel consumption and other key emission sources. The trade flows between the EU and China will be influenced by carbon pricing, regulation and standards that are implemented domestically. Moreover, the EU is currently redefining its foreign policy towards China. Given that there is a fundamentally different approach towards human rights, strong economic competition as well as a need for international and bilateral cooperation on climate protection with China, the relationship is complex 3 . The European Union thus is seeking new approaches to connect with China on climate policy, while at the same time to signal that red lines exist with respect to human rights and intellectual property rights violations.

Over the last decades, many production processes have been outsourced to China and the People’s Republic was successful in becoming the global economic powerhouse with an increase in world income from the end of the 1970 of 5% to over 17% in 2016 4 . Yet, this immense economic success came along with high emissions and nowadays China has a share in global emissions of around 28%. The highest share of Chinese emissions stems from coal (70% in 2019 5 ), cement production is the sector with the highest single share in overall CO2-emissions (0.8% of chinese emissions in 2019). The 2020 economic recovery after the Pandemic was driven by carbon-intensive industries 6 . The Chinese government made an announcement on its future climate targets last September. Before 2030 Beijing aims at peaking the domestic emissions and before 2060 it plans for carbon (not climate) neutrality 7 .

The EU is in the process of reforming its legislative activities to deliver on the 2030 climate target of minus 55% (compared to 1990 emissions) and climate neutrality by 2050. The new proposal by the Commission for an EU trade strategy, published in February, holds a potential, too, to create more momentum for climate action in the EU and internationally. In the Trade Policy Review the Commission emphasises that the EU trade policy should react to rising uncertainty due to political and geo-economic tensions, in particular the rapid rise of China, global technological evolutions and the pandemic. Climate change, biodiversity loss and environmental degradation need to be tackled with a green transition. The proposal also signals to important trade partners like China that the EU actively will keep up its own interests by increasing its strategic autonomy, with the Green Deal agenda and the intention to keep up leadership, own values and engagement 8 .

As part of the legislative climate package (“Fit for 55”), the Commission has planned for a concrete proposal for a Carbon Border Adjustment Mechanism (CBAM) announced in July 2021. The idea of charging a CO2-price for imported goods has brought carbon pricing to the attention of trade policy experts and policymakers. The CBAM is supposed to address the risk of carbon leakage for energy intensive industries. The ultimate goal is to prevent the relocation of emissions from the EU to third countries. So far, the EU applies free allowance allocation and electricity cost compensation to that end. Sectors like cement, steel, aluminium, and chemicals receive up to 100% emission certificates for free, depending on their actual efficiency, exposure to trade and their CO2-intensity. Moreover, with the CBAM the Commission hopes to make an impression on countries that do not show much ambition in following the EU climate policy example 9 .

By November 2021, when the 26th Conference of the Parties (COP 26) takes place in Glasgow, all parties to the Paris Agreement are asked for their renewed nationally determined contributions (NDCs) and long-term climate plans. China still has to make its announcements an official NDC.

In the mix of trade and climate policy approaches by the EU towards China, the CBAM could potentially play an interesting role. Whether it will become a game changer in EU China climate relations will depend on a number of factors, such as human rights issues, EU-China intellectual property rights and investment negotiations, the political pressure from US trade and climate policy put on China. The CBAM could facilitate more cooperation in dealing with emissions from energy intensive industries and the traded goods from sectors like steel and cement. Cement production alone is responsible for around 8 % of global CO2-emissions 10 and China produces the largest part of cement globally, about 60 %. Yet, given the trade tensions that already exist between the EU and China, the CBAM could also add another complexity to the list of unresolved issues between the two players.

Connecting 2021 to the mid-term

The climate policy decisions in the EU and in China (and other big economies) this year will be key for what can be achieved globally by 2030 and beyond. The EU has already a longer list of proposals for legislation to implement the Green Deal, including the reform of the EU ETS, the Energy Tax Directive, and more 11 . The full “Fit for 55” package will induce climate action with a view to the new climate targets. Also, the EU managed to couple the funds for the economic recovery after the Pandemic 12 with its Green Deal and with the new EU multiannual financial framework. Public money will thus be partly earmarked for climate policy purposes.

As the US government returned to the international negotiation table 13 , started its own very ambitious climate policy agenda and announced a similar set of climate targets as the EU did 14 , there is a stronger signal now that transatlantic cooperation will set the pace when it comes to creating markets for climate-friendly products. The US plans for 100% “pollution-free” electricity production by 2035 15 and stricter regulation for the transport sector, buildings and industry will be added. If the plans materialise, this would help to create critical market sizes for green products in the US along with the EU for the next decade.

China, on the other hand, has not yet decided to speed up climate protection. The country holds on to a capacity increase in coal combustion 16 , investments that will last for at least two or three decades. As China consumes around 50 % of global coal supply alone for this purpose 17 , a decline in coal use would make a huge difference for global emissions. Moreover, fossil fuel capacities are promoted by Beijing also externally through its Belt and Road Initiative that reaches out to its neighbouring countries, and also to Africa and the Balkan countries 18 . Currently the forecasts for China’s emissions trajectory are rather pointing to insufficient and slow progress towards emissions reduction 19 . This is contradicted to a certain extent by the high investment in renewable energy, where China is a world leader in absolute and relative terms.

In 2021, the international climate policy is fully focused on the COP 26 in November in Glasgow. By then all parties to the Paris Agreement are supposed to have handed in their new climate commitments for the mid- and the long-term. Thus, major summits, like the Leaders Climate Summit in April 2021, the G7 summit in June, the G20 Summit in October are having a role in motivating laggards to bring their offers to the table. Finishing the Paris Rulebook, by agreeing on the settings for international emissions trading and the rules for transparent reporting on emissions data, as well as reliable financial commitments to help developing countries, belong to the key issues that need to be addressed. The EU plus the UK and the US are pairing 20 to build a renewed coalition of progressive countries that drive climate protection. Trade cooperation is one of the building blocks, it seems.

Also in 2021, the international trade system of the WTO is at the centre of attention of multilateralism. Reforms are overdue. Decades in which new regional and bilateral trade arrangements flourished, the US blockage of the dispute settlement system, with an increasing number of anti-dumping cases, the EU-China conflict about the status of China as a market economy, and many more issues have undermined the functioning of the multilateral trade order. The plan to negotiate a Doha Development round was put on hold – a frustrating situation for developing country members.

After COP 26, the WTO will hold its 12th Ministerial Conference and hopes are high that some of the issues, in particular the needs for a new round of trade talks that help developing countries’ agendas, can be resolved. But also the pressure is rising at the WTO to help countries in implementing their NDCs and defining a role for the WTO in this respect 21 . With the EU’s plans to introduce carbon border adjustments for some energy-intensive sectors, however, the WTO system and its forums will experience another stress test. More proactive proposals, in particular the revival of talks about a plurilateral environmental goods agreement (EGA), are emerging in the debates 22 . Under an EGA, tariffs for climate-friendly technologies and goods could be lowered, and trade could add to a speedier implementation of national climate policies. If the WTO and the settings of regional and bilateral trade talks can become “greener”, e.g. by also considering the climate targets and measures, by using reporting tools for climate policies that relate to trade and by formulating common interests on how reforms could help advancing climate protection, this would increase chances that the climate policy implementation would gain speed with a view to 2030 targets.

Carbon embedded in trade and the EU CBAM

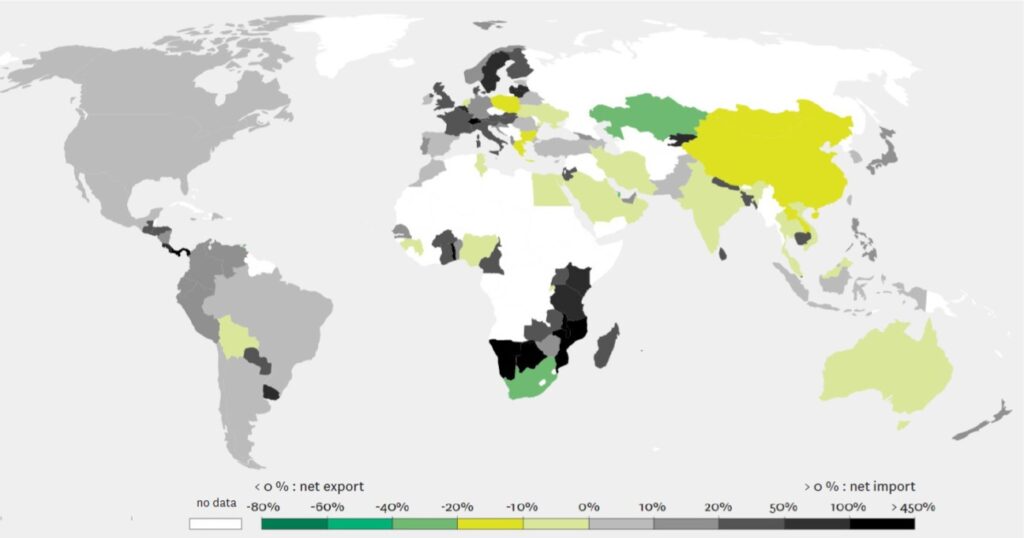

Traded products cause carbon emissions in the country of production. These emissions are not accounted for in countries of consumption. Yet, the overall picture shows that industrialised countries emissions balances benefitted over time from the outsourcing of production to developing countries (Figure 1 23 ).

Particular attention has been paid by researchers to the flows of CO2 since the 1990s globalisation kick-off. As a pattern, the industrialised countries are mostly net importers of embedded carbon, while emerging economies and some developing countries are net exporters. Peters and Hertwich described this effect from international division of labour as carbon leakage 24 .

China’s high share in global emissions has evolved both from its domestic growth, driven also by the increasing share of China in international trade 25 . In 2014, 26% of the EU-28 emissions relating to final demand were emitted in China. They were embedded in Chinese goods delivered to the EU. Outsourcing CO2-intensive activities to China, and importing the related goods, contributed to Europe’s decline in emissions and China’s increase. This also holds for other countries 26 .

The EU CBAM will have an influence on these trade flows. The CBAM is supposed to prevent future relocation of industries outside the EU or changes in trade flows due to asymmetric climate regulations. This type of relocation would undermine the EU effort to reduce emissions from EU production. However, although the EU is the third largest trading partner worldwide, going it alone will be risky, from a legal, a political and an economic point of view 27 .

The CBAM will most likely start with a few sectors in order to test the approach. Among those to be included are cement and steel, often mentioned in consultations. Both contribute large shares, respectively about 6% and about 8% 28 , to global emissions and range among the sectors at risk of leakage 29 and are traded between the EU and China. The full list of at-risk-sectors is longer, including chemicals, fertilisers, aluminium and other energy-intensive industries. An extension of the CBAM coverage is unclear, yet the legal draft is supposed to be “sector-neutral”, so that an extension will not need a new legal proposal.

Figure 1 • Share of carbon dioxide (CO₂) emissions embedded in international trade imports and exports in 2018

The details of the EU CBAM legislative proposal are still unclear, some features are very likely though. The roadmap 30 , issued by the Commission in March 2020, included different ways to connect a border levy to EU internal policy approaches to price CO2. They include a border tax, a customs duty and an extension of the EU ETS. The key carbon pricing instrument in the EU is the EU ETS, while a CO2 tax is not likely to emerge at all, however some of the member states have individual CO2-taxes in place 31 . A virtual EU ETS for importers is a likely outcome for the CBAM design. It would mean that importers will be paying the EU ETS CO2 price, but will not participate in trading not carbon trade the allowances.

For the mid to long-term, the CBAM’s success will be mirrored in a decreasing differential between trade partners – it would be successful if it eventually phases out, as trade partners follow the EU example and reduce emissions. Another CBAM potential is that it could trigger more transparency in emissions data around the globe, because companies and countries want to show that they improve their emissions performance or even become climate-neutral. Last but not least, international standards for certification and monitoring of emissions could be pushed this way.

The CBAM as intended by the EU will probably not cover the full carbon footprint of traded goods (from cradle to grave) but rather the direct emissions and those from electricity use, as it is the case with the EU ETS.

A calculation of a CBAM for imports will have to take into account several elements. It should relate to the carbon content of imports, that is, some data and assumptions are needed on how much CO2 is caused during the production abroad. In order to comply with WTO rules, there should be no discrimination between trade partners of the EU. Thus, using the EU-average for calculating direct CO2 emissions of a sector would be a good starting point to calculate how much CO2 is embedded in an imported good. For indirect emissions from electricity use, the calculation could use the average country-of-origin CO2-intensity. For both assumptions, the EU average for direct emissions and the country-of origin emissions from electricity, the EU should allow that companies individually prove that they are performing better than these averages. Moreover, in order to not create double protection for European producers through the CBAM, the degree of free allowance allocation needs to be subtracted from the calculation, either as a credit for the carbon price that is used or as a credit for the assumed amount of CO2 that is embedded in imports Also the price that will be charged at the border under a virtual ETS, would need to be reduced by a CO2 price, if any, in the exporting country. It is very important to avoid double pricing for imported products.

Implications for and reactions by China

A rough estimation of the carbon price that Chinese firms would face under a CBAM for the steel sector can be made based on the latest trade data for steel. The steel imports from China to the EU-27 were worth 1.7 billion Euros on average in 2019 and 2020. The traded weight in tonnes was 1.9 million tonnes in the 2 years average. If a CBAM would apply the average EU CO2-intensity of 1.3 tonnes of CO2 per tonne of steel (NACE 2410 32 ), then the imported CO2 from China from steel alone would add up to 2.5 million tonnes per year. Putting a price of 25 euros would in theory mean a 62,5 million euros bill. In light of the calculation details, however, this has to be corrected for free allowances that the EU steelmakers have received. The steel industry in Europe has received up to 100 percent free allowances during the last years. As long as this is the case, the Chinese imports would not be charged. Yet, the future decrease in free allocation, as planned for under the EU ETS until 2030, will define whether or not a CBAM will charged in the future. Also, China has started an ETS itself and the CO2-price has to be credited for. Moreover,the trade in steel is more complex than the focus on imports suggests. There is considerable export of steel from the EU, including export of steel products to China 33 . Thus, the steel industry is also subject to carbon leakage outside Europe, which occurs if it loses market shares in other markets to producers with higher CO2-intensity of steel products.

A number of reactions could arise from this first test of the CBAM for steel. China’s industry is carbon-intensive. So the assumption that the EU average will be used to calculate direct emissions for the CBAM could be in favour of China’s producers. But also Chinese producers -mostly state-owned enterprises – could reshuffle clean energy input to exported goods to bring down the CBAM bill. If cement or steel is being produced with renewable power (for steel this is relevant mostly for recycling of scrap steel), then a proof that the CO2-intensity of the electricity for exported goods is below Chinese average could help reduce the CBAM price. Reshuffling as such is not desirable from a climate policy point of view as it would mean that fossil sources will simply be used for other purposes and there is only limited reduction of emissions as a reaction to the CBAM.

Also, China could consider diverting its deliveries to the EU via countries that do not have to pay the CBAM, either because they have negligible amounts they export to the EU, or because they are exempt due to their status as Least Developed Country (LDC). Such exemptions are likely to be part of the CBAM design in order not to burden poor countries and to keep the fairness principle under the Paris Agreement.

The EU has a rather long history of steel trade conflicts with China 34 . The EU claims that the Chinese state-owned companies export overcapacities that they sell at prices below production cost to Europe 35 . If this kind of dumping can be proven, the WTO rules allow for countervailing measures. The EU has implemented countervailing duties on Chinese steel products and has launched new investigations last year. The issue has not yet been resolved under the WTO dispute settlement system or elsewhere.

The CBAM would thus add to the tensions. It will be regarded by Chinese officials as another means to suppress Chinese steel (and also other) imports to the EU. It is highly likely that the CBAM will be politicised. In international forums and EU-China-meetings first, partly fierce reactions emerge 36 . China together with other members of the BASIC group (Brazil, South Africa, India) protested against the EU plan 37 .

The way forward

The EU relationship with China is in a phase of strategic reorientation. The threefold characterisation of China by the EU as a political rival, competitor and cooperation partner shows that the complexity of handling the ties with China are increasing. Using climate and trade policy to address this on an issue-by-issue basis may become more relevant to EU policymakers. The CBAM thus could become a tool to put economic pressure on China, for instance used in order to push Beijing to reduce coal combustion. 2021 is a very important year in this respect. The upcoming high-level meetings will show how far the EU and China will be able to agree on climate cooperation in light of the mounting pressures put on China, and on their trade priorities in a manner that is mutually beneficial.

Notes

- European Commission, “The EU budget powering the recovery plan for Europe”, Communication from the Commission, May 2020. European Commission, “A Union of vitality in a world of fragility”, Annexes – Commission Work Programme 2021, 2020.

- Client and Supplier Countries of the EU27 in Merchandise Trade (value %) (2020, excluding intra-EU trade), European Commission, DG TRADE.

- J. Oertel, J. Tollmann, B.Tsang, “Climate superpowers: How the EU and China can compete and cooperate for a green future”, European Council on Foreign Relations, January 2021.

- S. Brakman, C. van Marrewijk, “China: An Economic powerhouse that depends on the Rest of The World – RSA Main”, January 2020.

- Global Carbon Project, 2019.

- M. Grant, H. Pitt, K. Larsen, “Preliminary 2020 Greenhouse Gas Emissions Estimates for China”, Rhodium Group, 2021.

- The neutrality targets take different points of reference. The EU is aiming at climate neutrality. This comprises all Greenhouse Gases. The goal of carbon neutrality is aiming at net-zero CO2-emissions only. Thus, it is not as ambitious as climate or GHG-neutrality. See O. Geden, J. Rogelj, A. Cowie et al., “Three ways to improve net-zero emissions targets”, Nature, 2021.

- European Commission, “Trade Policy Review – An Open, Sustainable and Assertive Trade Policy”, Communication, 2021.

- S. Pickstone, “Timmermans says he hopes not to use CBAM against China” Ends Europe, May 2021.

- “Q&A: Why cement emissions matter for climate change”, Carbon Brief, September 2018.

- European Commission, “Trade Policy Review – An Open, Sustainable and Assertive Trade Policy”, Communication, 2021.

- European Council, “Special Meeting of the European Council”, Conclusions du Conseil, 17-21 July 2020.

- “Executive Order on Protecting Public Health and the Environment and restoring Science to Tackle the Climate Crisis”, The White House, 20 January 2021.

- “Executive Order on Tackling the Climate Crisis at Home and Abroad”, The White House, 27 January 2021.

- M. Darby, I. Gerretsen, “Which countries have a net zero carbon goal?”, 2019.

- In February 2020, China had about 250 GW of new coal plants under development. Reuters Staff, “China’s new coal power plant capacity in 2020 more than 3 times rest of world’s – study”, Reuters, February 2021. The latest chinese FYP (2021-2025) does not plan for a decrease during 2021-2025, as even if moderate, the coal consumption growth is planned to be positive (0.1% to 0.9% per year). See “Q&A: What does China’s 14th ‘five year plan’ mean for climate change?”, Carbon Brief, March 2021.

- BP Statistical Review of World Energy, BP, June 2020.

- [ndlr] See in the issue the article of H. Chen and C. Springer titled “China’s Uneven Regional Energy Investments”, page 92.

- Carbon Brief, op. cit.

- United States Department of State, Joint declaration : “The United States and the European Union Commit to Greater Cooperation to Counter the Climate Crisis”, 2021.

- C. Deere Birkbeck, “How can the WTO and its Ministerial Conference in 2021 be used to support climate action?”, One Earth, Vol 4, May 2021.

- M. Sugathan, “Addressing Energy Efficiency Products in the Environmental Goods Agreement”, International Centre for Trade and Sustainable Development, 2015.

- Source: Peters et al, Global Carbon Project.

- G. P. Peters, E. G. Hertwich, “CO2 Embodied in International Trade with Implications for Global Climate Policy”, Environ. Sci. Technol., 2008.

- S. Heli, “CO2 emissions embodied in EU-China trade and carbon border tax”, 2020.

- K. He, E. G. Hertwich, “The flow of embodied carbon through the economies of China, the European Union, and the United States”, Resources, Conservation and Recycling, 2019.

- L. Hook, “John Kerry warns EU against carbon border tax”, Financial Times, mars 2021 ; G. Zachmann, B. McWilliams, “A European Carbon Border Tax: Much Pain, Little Gain”, Policy Contribution, May 2020.

- C. Hoffman, M. Van Hoey, B. Zeumer, “Decarbonization challenge for steel”, McKinsey, June 2020.

- “Carbon leakage refers to the situation that may occur if, for reasons of costs related to climate policies, businesses were to transfer production to other countries with laxer emission constraints. This could lead to an increase in their total emissions. The risk of carbon leakage may be higher in certain energy-intensive industries”, European Commission, Climate action, EU ETS.

- Commission Européenne, “ EU Green Deal (carbon border adjustment mechanism). Inception Impact Assessment ”, 2020.

- For instance France has a CO2-tax since 2014 on fossil fuels. Sweden has a CO2 tax since 1991.

- Eurostat, “Statistical classification of economic activities in the European Community”, NACE code 2410 “Manufacture of basic iron and steel and of ferro-alloys”.

- 20.5 millions tons of finished steel products exported from the EU in 2019, almost as much as the import of finished steel products (25.3 millions). China is the 4th export destination, 2020 European Steel in Figures, Eurofer, 2020.

- European Commission, “General overview of active WTO dispute settlement cases involving the EU as complainant or defendant and of active cases under the Trade Barriers Regulation”, 2013.

- European Commission, “The European Union’s Measures Against Dumped and Subsidised Imports of Solar Panels from China”, 2016.

- K.Taylor, “Chinese president slams EU carbon border levy in call with Macron, Merkel”, EURACTIV, April 2021.

- South African Government, “Joint Statement issued at the conclusion of the 30th BASIC Ministerial Meeting on Climate Change hosted by India on 8th April 2021”, 2021.

citer l'article

Susanne Dröge, The EU and China: Climate and Trade Increasingly Intertwined, Sep 2021, 159-164.

à lire dans cette issue

voir toute la revue