Is Chinese Industrial Policy Compatible with its Environmental Ambitions

Anaïs Voy-Gillis

Associate researcher at CRESAT (University of Haute-Alsace)Issue

Issue #1Auteurs

Anaïs Voy-Gillis

21x29,7cm - 153 pages Issue #1, September 2021

China’s Ecological Power: Analysis, Critiques, and Perspectives

On 22 September 2020, Xi Jinping made a commitment to the United Nations General Assembly that China would achieve carbon neutrality by 2060 1 , even though the country is the world’s largest energy consumer and the largest emitter of carbon dioxide (CO2). This goal therefore seems particularly ambitious in view of its production structure and organisation, which are mainly centred on heavy and polluting industries, as well as its growth goals.

Although China’s environmental commitments begin before 2020, their effects are still somewhat limited. For instance, as early as 2007, President Hu Jintao supported the idea of an ecological civilisation 2 , which he saw as the foundation for a renewed civilisational leadership and would define a new direction of Chinese development.

And so, the environmental issue is also a geostrategic asset on which China has been counting to strengthen its international leadership at a time when Donald Trump’s United States was turning away from the matter. Nevertheless, despite China’s national five-year plans, its race for growth since the late 1970s has caused irreversible damage to the environment and biodiversity.

The environmental question is mainly addressed through the issue of carbon, whereas in reality it requires a systemic approach. While carbon neutrality is a laudable and necessary goal, it is rarely sufficient on its own. Focusing on carbon can have devastating and disruptive effects on ecosystems. For instance, the construction of dams has serious consequences for entire communities 3 and threatens water resources in areas downstream, with both environmental and economic consequeneces.

Environmental damages must not only be considered in relation to Chinese territory, but also for peripheral territories where the country may also be tempted to locate some of its most polluting and carbon-intensive activities. One country’s carbon neutrality should not be achieved at the expense of another’s.

The Chinese central government has progressively strengthened its consideration of environmental concerns by developing a regulatory framework for environmental protection, by adopting a proactive policy in its five-year plans, and by investing in renewable energy. These commitments have been the subject of much criticism, not only regarding their true ambition, but also in how these goals are carried out at the local level, as well as China’s capacity to make meaningful changes to its productive model to move towards more environmentally sound and sustainable industries.

China’s desire to move towards carbon neutrality raises many questions about this ambition’s compatibility with the country’s growth goals. While the issue of environmental protection and our system’s transformation should be the central concern of all future international agreements, it is hardly mentioned in the Comprehensive Agreement on Investment (CAI) between the European Union and China which was announced this past December 30th 4 . Consequently, questioning the compatibility of China’s environmental ambitions with its industrial policy also leads us to broaden the debate to question the Western production model. In fact, by de-industrialising, European nations have transferred part of the environmental responsibility linked to their consumption habits to external parties — including the responsibility related to waste management.

A growth model incompatible with China’s environmental ambitions

China’s modernisation since the end of the 1970s has been a massive process of industrialisation and urbanisation 5 with an average annual economic growth of about 9% 6 . The expansion of construction has increased energy-intensive production such as aluminum, steel, and cement. China’s intensive growth has also not been without consequences for the environment, as it has been dependent on an intensive use of natural resources, very high energy consumption, and long-term pollution of soil, water, and air. Decades of rapid economic growth have reduced nature to the resources it produces and the wealth that can be derived from them 7 .

This massive and destructive exploitation of natural resources has many serious consequences today: diseases 8 , unusable land, artificialization of arable land, etc.

The Chinese production model suffers from inconsistencies that have shaped its development. For instance, the government has supported or supports the development of heavy industries through subsidies or by being a shareholder in public companies, which has led to situations of overproduction in several sectors. In Europe, the most well-known example is certainly steel. Competition is no longer based on quality, but on prices and quantities sold. Each company tries to sell more and at a lower cost, without taking into account the devastating environmental impacts of this type of production and without massive investment in production units to reduce negative externalities. Moreover, this situation has had harmful effects on other industries, particularly European ones who find themselves competing with low-cost, subsidised steel. This prompted the European Commission to take anti-dumping measures in 2016 when the European manufacturing base was experiencing lasting damage from this situation 9 .

However, without attempting to minimize the environmental consequences, this development model should be viewed in the context of the global economic pattern that has been in place since the mid-1970s. In 1979, under the leadership of Deng Xiaoping, China moved towards a strategy of opening to Western nations by focusing on developing its industry, and in particular its heavy industries in the eastern provinces of the country 10 . It has become what is commonly referred to as the “workshop of the world”, though this has not been driven solely by its openness to the rest of the world. This was made possible by the spread of a shared belief in many Western countries that it was necessary to move away from manufacturing activities because they were considered to be of lower value and no longer necessary for the development of these nations. Supply chains were fragmented in the search for greater cost optimisation to the detriment of independence and economic sovereignty considerations.

China has relied on exports of low-cost products to satisfy world demand while developing strategies for acquiring technologies in key areas such as the automobile industry by buying Volvo and Lotus, for instance, and by developing its own national leaders such as the China State Railway Group Company (CR) in the railway sector.

However, this enormous industrial development has relied on massive coal consumption to supply power plants. Coal is cheap in China because the country has abundant 11 and good quality resources, which do not require sophisticated facilities to exploit. Since the first Five-Year Plan (1953) presented it as the main source of primary energy for heavy industries (steel, metallurgy, chemicals), coal has been China’s main energy source This explains the considerable amount of time needed to move away from dependence on this energy. Coal is also used in the residential sector for heating homes and cooking food.

Its low cost makes it an energy favoured by industries. In 2019, for example, 58% of the country’s primary energy came from coal 12 . Fossil fuels combined represented 86% of primary energy consumption 13 compared with 48.1% in France 14 . This distribution is changing, thanks to investment in renewable energies, which now account for around 13% of primary energy consumption (8% for hydroelectricity and 5% for other renewable energies). However, coal-fired power plants continue to be built every year. The closure of coal-fired power plants in Europe and the United States is offset by the opening of new plants in China, despite the country’s carbon neutrality goal Global Energy Monitor, 2020. In 2020, 76% of the 50.3 GW of new coal-fired power generation capacity in the world were Chinese 15 .

To address pollution issues and achieve its environmental ambitions, China is investing heavily in renewable energy to meet the 30% target of its energy mix by 2030 16 . However, some of the energy produced by solar and wind power is not used and is often not connected to the central electricity grid. As Stéphanie Monjon and Sandra Poncet pointed out, “in the absence of significant technical progress, and without a major change in the way China’s electricity distribution system works, the installation of wind turbines and solar panels, even at a frenzied pace, will not be enough to reduce the demand for coal” 17 . It should be remembered that in order to achieve carbon neutrality in 2060, China intends to increase solar power capacity by a factor of 10 and wind and nuclear power capacity by a factor of 7 18 .

In addition, as of 1 January 2021, China has prohibited the import of “solid” waste on its territory, even though it has previously received up to half of the world’s total waste. This new tightening of regulations is in line with government policies adopted in recent years, including the ban on the import of 24 types of waste, including textiles and individual and household plastic waste, in 2017. Waste imported into China must now meet multiple criteria (quality, level of contamination). The country’s development has led to an increase in its waste production and by refusing to accept waste from the rest of the world, China intends to protect its environment by limiting the entry of polluting materials onto its soil. This will lead to an increase in the flow of waste to other countries in South-East Asia. For example, since 2018, the import of scrap metal has increased by 14% in Vietnam and a similar situation can be observed in other countries. This subject brings us back to the need to redefine European industrial development models in order to reconsider the materials used in products to move towards recyclable materials, the way products are designed to increase the share of bio-sourced materials, managing the life cycle of products by integrating this topic beginning with the design stage, and especially the way we consume in order to drastically reduce waste production. The current system’s lack of sustainability must push us to find recycling solutions, even if the economic cost remains high.

A systemic approach to industrial and environmental issues

In its Five-Year Plan, published in 2011, the Chinese government announced the need to “build a sustainable, environmentally friendly society”. To achieve its goals, it must strike a balance between economic growth, energy security, and environmental protection. The 2021-2025 Five-Year Plan intends to refocus the country’s economy on the domestic market and emphasises food supply, energy, and technology. The government also aims to reduce the country’s exposure and vulnerability to external shocks. This plan reflects China’s industrial ambition to accelerate scientific and technological development, particularly in the field of quantum technology and high value-added industrial production, while also taking advantage of lower production costs than in other developed countries. This ambition was already part of its “Made in China 2025” 19 plan and has been reinforced by US sanctions. China intends to increase its research and development (R&D) expenditure by 7% per year by 2025 which would represent a total expenditure of 490 billion euros in 2025.

In comparison, R&D expenditure was €51.8 billion in France in 2018 and about €318 billion for the whole European Union in 2017. Through these measures, the Chinese government aims to pursue the transformation of its economic model, which was based on the over-consumption of energy, the production of low value-added goods, and an abundant labour force for decades, into a model centred on technology, innovation, and capital investment.

China is therefore expanding into various industrial sectors of the future, including that of the electric vehicle. The density of its population is an asset that enables the country to compete with foreign electric vehicle manufacturers for exports while developing its domestic market. As a reminder, China had more than half of the world’s electric vehicle fleet in 2018 and it has adopted a systemic approach to this matter. Electric vehicles solve a pollution issue. To encourage the development of this type of vehicle, the country has set up infrastructure to support their sale as well as production capacity. It has also put in place a strategy to control supplies, notably through the New Silk Roads.

In addition, China has become a major player in the mining industry. The country has developed a domestic mining sector but is also increasingly acquiring resource exploitation rights or sites in Australia, South America, and Africa. Given the resources allocated and the nature of the companies 20 , China is becoming a major player, which will accentuate the dependence of other nations on it 21 . In contrast, European manufacturers have fallen behind in this sector due to lack of anticipation and a strategic choice to initially focus on solutions other than electric vehicles. Moreover, the European manufacturing base is not necessarily geared toward the production of electric vehicles. For instance, Europe is only just beginning to set up factories to produce batteries for electric vehicles, although this is a key component. Asian countries have a more advanced command of this type of technology, which gives them an advantage in the electric vehicle market. It has also put in place a strategy to control supplies, notably through the Belt and Road Initiative. Furthermore, China has become a major player in the mining industry, which plays a key role in many of the value chains of the energy transition, such as electric vehicles. It has developed a domestic mining activity, but it is also multiplying its acquisitions of resource exploitation rights or sites in Australia, South America and Africa. In terms of resources allocated and nature of the companies, China is becoming a major player in this industry, rapidly increasing the dependence of other nations on its companies’ services and materials. For example, according to a study released by the European Commission, China was the world’s leading supplier of 30 of the 43 individual critical raw materials. This includes all rare earths and critical raw materials such as magnesium, tungsten, antimony, gallium and germanium. It should be noted, however, that although China is the world’s largest supplier, EU Member States can also source certain materials from other producing countries such as Mexico for fluorite, Russia for tungsten and Kazakhstan for phosphorus.

However, it is clear that while China has strong industrial and technological ambitions, it does not have the same commitment to achieve its environmental ambitions. The environmental component is not the subject of significant measures in the 14th Five-Year Plan, which raises questions about the ability of the country to achieve its goals. For instance, unlike the 13th Plan, there is no maximum threshold for energy consumption over five years. The 14th Plan also does not set a maximum threshold for CO2 emissions, or take steps to prohibit new coal-fired power plant projects. On the contrary, its goals do not represent a significant transformation of China’s ambitions. For example, carbon intensity goals remain the same as in the 13th Plan, the energy intensity target is 13.5% for the period 2021-2025 compared to 15% for 2016-2020. At best this will allow the current level of emissions to be maintained, but not drastically reduced.

As the plan does not set a cap on emissions, they will depend on the country’s actual growth. According to a study by the Centre for Research on Energy and Clean Air (CREA), China could meet its targets if its growth is between 5 and 6% per year 22 . There is also a strong possibility that the country will not meet its goals, as has been the case in the past. For instance, it has exceeded the CO2 intensity targets set out in its two previous five-year plans, as noted by Carbon Brief 23 .

Questioning the effectiveness of institutions and legislation

The five-year plans are non-binding guidelines for local authorities. Therefore, the consensus at the central level may not be reflected at the local level, as Mylène Gaulard explains when she talks about the ‘myth of an omnipotent state’

24

. For several years, the inconsistencies between the different levels have been reinforced by the system of evaluation and promotion of local authorities.

The first criteria considered were economic profitability and the preservation of social consensus, i.e. GDP growth and job creation. But environmental policies generally produce results in the long term, while local authorities change every three years. Since the 12th Plan, criteria for environmental protection and energy intensity reduction have been included in the performance evaluation of regional civil servants to ensure that ambitions are translated into concrete actions at the local level.

The National Environmental Protection Agency has very little influence and power against large state-owned enterprises and other local offices. It is under the responsibility of local authorities, which can impose their vision of the missions 25 . Furthermore, the Ministry of Environmental Protection (later renamed Ministery of Ecology and Environment) has little or no influence on local authorities. We can also observe a very high degree of fragmentation within the environmental bureaucracy. For example, offices exist at different levels (province, county, municipality) but they are independent of each other and may pursue different goals and strategies.

Overlapping areas of authority make conflicts of interest unavoidable, increase obstacles, and lead to inefficiency in decision-making at different levels. A lack of power also has repercussions on the application of laws. In 2018, for instance, according to a survey conducted by the Chinese Ministry of the Environment, 7 out of 10 companies did not comply with environmental standards despite a 2016 law on the taxation of emissions from industrial activities (excluding CO2 and nuclear waste) 26 . There are many cases of the law being circumvented which can also be explained by regulations that are sometimes vague, making their implementation complex. For example, the regulation on trucks specifies that vehicles that represent an “obvious danger” must be taken off the road without giving any further details. The combination of strict standards and unclear roles and responsibilities between institutions results in no institution taking real responsibility for controls.

Environmental concerns are becoming a central issue in China with the increase in cancers that have made pollution and its consequences highly visible. However, environmental movements are not coordinated on a national level and tend to be local. The response of authorities to any public concern over a particular factory or project, particularly when it comes to chemicals production plants 27 , is usually to cancel the project and transfer it to another location. Problematic factories are relocated to less populated and poorer areas. For example, a project rejected by the population of the coastal city of Xiamen (south-east), Fujian province, in 2007 was relocated in the same province to Gulei, a less densely populated area. It should be noted that this factory experienced a first explosion in 2009, without injury, and a second in 2015, injuring at least twenty people 28 .

Censorship and repression are another reason for limited engagement. Sanctions are applicable to anyone who challenges party policy, and they are imposed as soon as movements are considered dangerous to social and political stability. For example, in 2016, a protest against air pollution in Chengdu (capital of Sichuan province) was dispersed by the police. Protest leaders were arrested and the official media censored 29 . Some environmental NGOs 30 have been allowed to develop, but their freedom is restricted, and they operate within the limits set by the central government which generally means that they can carry out actions that are considered harmless, such as raising awareness of environmental issues.

In addition, many organisations do not have legal status and are not eligible for funding. The possibilities for civil society to act are therefore greatly reduced.

Environmental ambitions are absent from EU-China comprehensive agreement

The European Union and China have only recently agreed in principle on a comprehensive investment agreement, even though discussions began in 2013. However, on 4 May 2021, the European Commission announced, through its Vice-President Valdis Dombrovskis, that the ratification process was on hold due to the political climate between the EU and China. This agreement had raised several questions on the economic front, but above all there was a serious lack of ambition on the environment. While it is true that the agreement establishes a reciprocal obligation to implement the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC) and the Paris Agreement, it should be noted that the Paris Agreement does not commit to results 31 . While China wishes to present itself as a leader in the fight against global warming, the European Union is struggling to position itself as a geopolitical power and to make its voice heard on the environmental issue.

The agreement aims to open the respective markets more widely to mutual investments. China will therefore benefit from greater access to Europe’s energy and manufacturing sectors, and, in return, it will commit to facilitating the entry of European companies into promising new markets such as clean vehicles, health, finance, and the cloud. Very few environmental commitments were included, even though there was an urgent need to build common and transnational solutions on the matter. There is also a need to rebalance trade between European companies constrained by high environmental standards and Chinese companies, some of which are subsidised by the State, which practice environmental and social dumping.

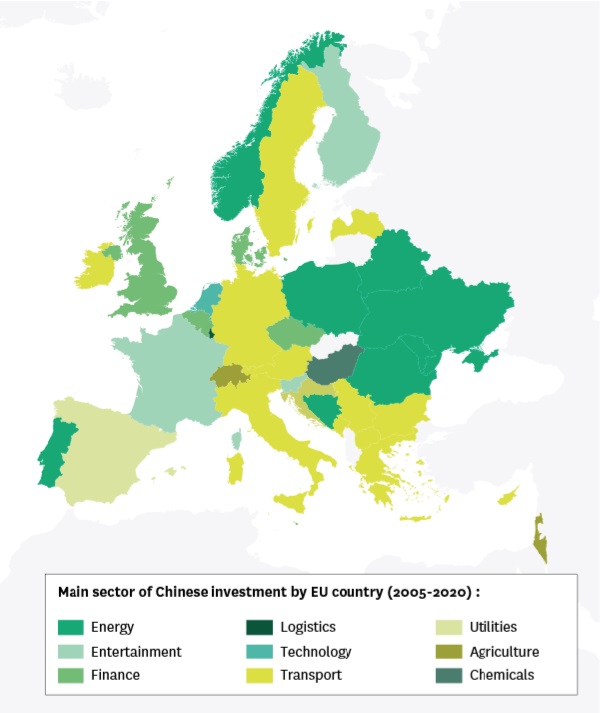

The agreement can be seen as Europe’s desire to harmonise the bilateral treaties signed by the different Member States with China. There is also a question of reciprocity in access to the market and to companies. In the last few years, several European flagship companies have been acquired by China, such as Volvo in Sweden, Pirelli in Italy, Lanvin in France, and Kuka in Germany. Between 2010 and 2020, Chinese groups made 650 acquisitions in Europe, including 174 in Germany, 102 in the UK, and 72 in France. Of the 72 French acquisitions, 40% were made by conglomerates that are wholly or partly owned by the Chinese state 32 . Chinese companies took advantage of the euro crisis in 2008/2009 to make several acquisitions in Europe, particularly firms in crisis. The global treaty could increase Chinese acquisitions in Europe, even if the European Commission wants additional tools to better protect European industries 33 . For example, on 11 October 2020, a screening mechanism for direct foreign investment came into effect at the European level. It is an undeniable step forward and is based on an exchange of information between Member States.

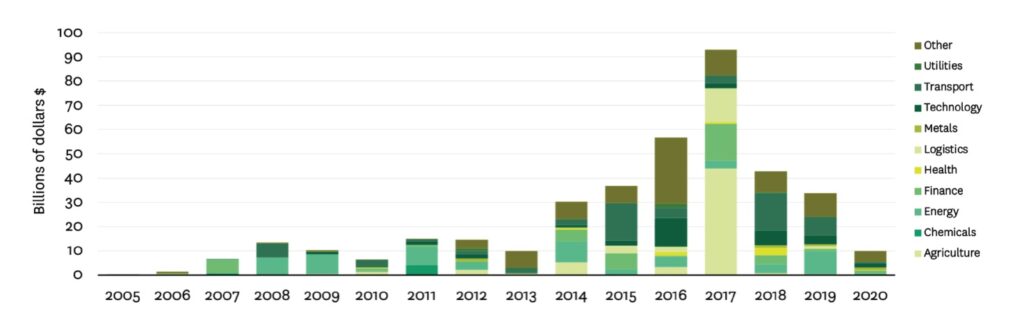

Figure 1 • Chinese investment in the European Union (28), by sector

Each state remains free to evaluate whether investment presents a risk or not. However, this mechanism does not apply to all investments, but only those likely to jeopardize security or public order. It will therefore be necessary to examine the use of this mechanism by the Member States (only 12 of which have a national filtering mechanism) and the reactions of the European Commission. The European view is that the mechanism should not be a means of preventing the free movement of capital for purely economic reasons, but some Member States may see it as a means of circumventing European rules to go further than simply protecting national security. Furthermore, Chinese acquisitions in Europe are diverse and therefore raise questions about the definition of strategic assets. It is therefore possible to divide Chinese investments as follows:

- Achieving technological breakthroughs: acquiring technologies, know-how and skills 34 to limit R&D efforts, thus saving time and money and focusing financial and human resources on the technologies of tomorrow such as clean vehicles, robotics, quantum, etc.

- Ensuring food safety: numerous food scandals have affected China, particularly in infant food, which has led the country to make foreign acquisitions in this area to secure its supplies.

- Acquiring a brand image: the acquisition of well-known and established European brands is a guarantee of quality because they often have a good brand image and are also a means of gaining a foothold in the European market, particularly in the automobile or apparel sector with so-called “accessible luxury” brands such as the SMCP 35 group or luxury brands such as Sonia Rykiel and Lanvin.

Even if the European market is open, European companies are subject to restrictions when investing in China. The rules have recently evolved in China, but for several years companies wishing to invest in China have been obliged to create joint ventures with local companies and to accept technology transfers. Since 1 January 2020, the Foreign Investment Law replaces three previous laws and lays out restrictions for foreign investment. Strategic sectors which relate to state sovereignty, such as information services, are closed to foreign companies. China has banned certain companies from entering its market and has worked towards the emergence of national competitors such as Baidu covering Google’s domains, Alibaba covering Amazon’s, Sina Weibo covering Twitter’s, etc. Other sectors such as telecommunications are also subject to investment restrictions.

One of the interests of the agreement was to review several years in which China has focused on developing bilateral relations with EU member countries. The projects were of various nature, but mainly concerned infrastructures. In Italy, for example, through the New Silk Roads, the ports of Genoa and Trieste were made available to Chinese companies wishing to establish themselves in Europe. In Greece, the port of Piraeus was turned over to the shipping company Cosco. In Spain, Cosco controls the ports of Bilbao and Valencia. As a result, China has an influential strategy on the Member States that could ultimately challenge European cohesion. The global agreement can therefore be seen as a means for the European Commission to avoid bypassing European authorities.

In addition to environmental issues, this agreement raises economic questions. It seems unbalanced since it binds the European Union more than China due to the nature of the Chinese system. While China has committed to joining the International Labour Organisation (ILO), it rarely respects all commitments made in international agreements. It has repeatedly violated its trade commitments in order to pursue its political and economic interests, such as when Australia denounced China’s policies in Xinjiang, Hong Kong, and Taiwan in spring 2021. As a reminder, since 2001 and its entry in the World Trade Organisation (WTO), China has not honored its commitments to respect human rights. And so, a geopolitical reading of the agreement reminds us that the European Union is not a political organisation and that it struggles to define a geopolitical ambition which unites the 27 Member States. Trade policy must be a foreign policy tool. This agreement, if it goes ahead as it is, will show Europe’s weak strategic vision, in contrast to China, which has a geopolitical vision. It will also expose the nations’ lack of ambition regarding environmental matters and the transformation of industrial models in order to achieve the established goals.

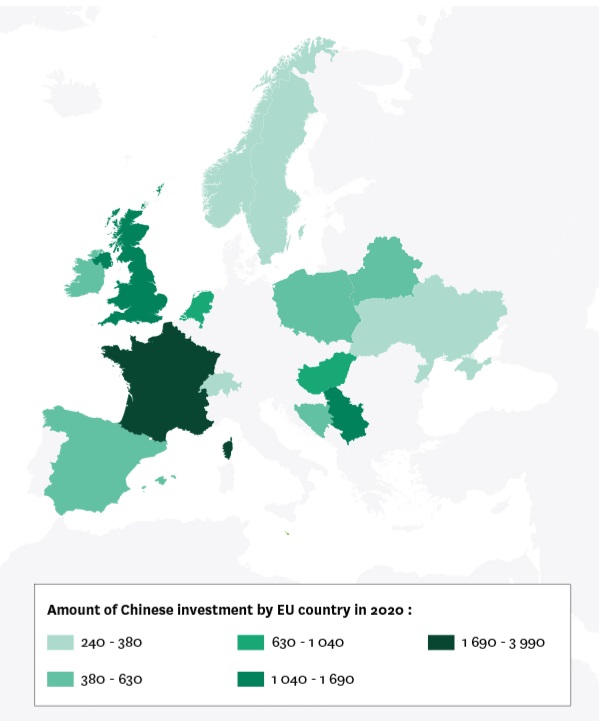

Figure 2 • Amount of chinese investment by EU country in 2020 36

Figure 3 • Main sector of chinese investiment (FDI) by EU country (2005-2020)

Conclusion

It is still early to judge the effectiveness of China’s environmental policy considering the progress the country still has to make. Moreover, it is possible to address the environmental issue more broadly by asking whether States have really become aware of the transformation required to achieve environmental goals. The more time passes, more drastic concessions will be required to achieve these goals. The emergence of a truly ecological society will require a deeper questioning of the functioning of the Chinese economy and institutions, starting with the end of the coal-based production model. In addition, the transformation of the Chinese model is not just a concern for China, given the current interdependence of economies and the global nature of the environmental problem. In other words, the environmental issue calls for a profound transformation of the production, distribution, and consumption models of all Western countries.

In addition to the coal issue, China needs to improve the efficiency of its industry, which is more energy intensive than world standards. It also needs to build sufficient energy infrastructure and put effort into innovating in the right areas, starting with the energy sector. The systemic approach is key, as the example of the electric vehicle shows. However, care must be taken to not create new environmental problems by aiming for carbon neutrality or to relocate the problem to other countries, as Western countries have partially done with the phenomenon of relocation.

China’s environmental ambitions also reflect a desire to be a leader in this area and therefore address geopolitical concerns. There is still a long way to go, but the fight against global warming is not and cannot be a competition. Each country must strive to reduce its overall environmental impact, not merely to achieve carbon neutrality, and to do so in a spirit of cooperation with other nations and to preserve the world’s shared resources.

Notes

- Statement by H.E. Xi Jinping President of the People’s Republic of China At the General Debate of the 75th Session of The United Nations General Assembly, Beijing, 22 septembre 2020

- C. Goron, “ Civilisation écologique et limites politiques du concept chinois de développement durable ”, Perspectives chinoises, 2018-4 | 2018.

- The Three Gorges Dam had significant social consequences with the displacement of more than 1.3 million people. The environmental impacts are also significant, with numerous landslides and the disappearance of certain species.

- European Commission, “EU and China reach agreement in principle on investment”, European Commission press release, 30 December 2020. The vice-president of the European Commission Valdis Dombrovskis indicated on Tuesday 4 May the suspension of the ratification process of the agreement concluded in December 2020, due to the tense political climate between the European Union and China.

- H. Liao, Y. Fan, Y. Wei, “What Induced China’s Energy Intensity to Fluctuate: 1997–2006?”, Energy Policy, Vol. 35, 23, 2007.

- According to data made available by the World Bank for the period 1975-2019. Over the period from 1961 to 2019, the average annual growth is just over 8%, which represents a GDP growth of about 122% over the period.

- J. Shapira, Mao’s War Against Nature, Cambridge University Press, 2001.

- Cancer is the number one source of illness in China. Several reports highlight the disastrous consequences of polluted water on certain villages where a majority of inhabitants develop cancer.

- European Commission, Report from the Commission to the European Parliament and the Council, 30 April 2020.

- He C., Wang J., “Energy Intensity in Light of China’s Economic Transition”, Eurasian Geography and Economics, vol. 48, no. 4, 2007.

- China has the fourth largest coal reserve in the world. At the end of 2019, China’s proven coal reserves were estimated at 141.6 billion tonnes of coal, or nearly 13.2% of the world’s reserves. This data comes from the Statistical Review of World Energy 2020, published annually by BP.

- Energy Information Administration, 2020.

- BP Statistical Review of World Energy, June 2020.

- In France, the share of renewable energy is 11.6% and that of nuclear energy is 40.3%. Ministry of Ecological Transition, Chiffres clés de l’énergie, Édition 2020, September 2020.

- Ibid.

- 13th Five Year Plan (2016 – 2020).

- S. Monjon, S. Poncet, La transition écologique en Chine. Mirage ou virage vert ?, Paris, Éditions Rue d’Ulm, 2018.

- As part of China’s 14th Five-Year Plan (2021-2025).

- «Made in China 2025» plan unveiled to boost manufacturing”, China News, May 2015.

- The major Chinese mining groups are almost all state-owned or semi-state-owned.

- J. Yves. “La sécurisation des approvisionnements en métaux stratégiques : entre économie et géopolitique”, Revue internationale et stratégique, vol. 84, no. 4, 2011.

- L. Myllyvirta, “China’s five-year plan: baby steps towards carbon neutrality”, Centre for Research on Energy and Clean Air, mars 2021.

- “Q&A: What does China’s 14th ‘five-year plan’ mean for climate change?”, Carbon Brief, 12 March 2021.

- M. Gaulard, “La lutte contre le réchauffement climatique en Chine, une nouvelle remise en question du Consensus de Pékin”, Développement durable et territoires, Vol. 8, no. 2, July 2017.

- S. Kuen, “La participation du public en droit environnemental chinois”, in C. Eberhard (dir.), Traduire nos responsabilités planétaires. Recomposer nos paysages juridiques, Bruylant, 2008.

- E. Gautreau, “Explain to us… China’s paradoxical environmental situation”, FranceTVinfo, 8 January 2018.

- For example, there have been numerous protests against plans to build factories producing chemicals such as paraxylene, a toxic petrochemical, as in 2007 in Xiamen (south-east), in 2011 in Dalian (north-east) and in 2013 in Kunming (south-west). On each occasion, the local authorities eventually abandoned the projects concerned

- “Violent incendie après une explosion dans une usine chimique”, Courrier international, 7 April 2015.

- G. Pitron, “En Chine, la ligne rouge du virage vert”, Le Monde diplomatique, July 2017.

- NGO with official status (registered with the Ministry of Civil Affairs as a social organisation), NGO with semi-official status (registered as a company), NGO with unofficial status (no official recognition or existence), governmental NGOs established by government agencies (hybrid status specific to China).

- A. Canonne, M. Combes, N. Roux, I. Verheecke, “ Accord UE-Chine : l’UE rassure les investisseurs au mépris des droits humains ”, Note de décryptage, AITEC – ATTAC France, April 2021.

- J. Zaugg, “Comment la Chine fait main basse sur les pépites européennes”, Les Échos, April 2021.

- European Commission, “Mise à jour de la stratégie industrielle de 2020 : construire un marché unique plus solide pour soutenir la reprise en Europe”, Press Release, European commission, 5 May 2021.

- S. Guillou, “ Doit-on s’inquiéter de la stratégie industrielle de la Chine ? ”, OFCE, Policy Brief n°31, January 2018.

- The SMCP group comprises the brands Sandro, Maje, Claudie Pierlot and De Fursac.

- Source: The American Enterprise Institute, China global investment tracker, Autumn 2020, consulted on 17 June 2021.

citer l'article

Anaïs Voy-Gillis, Is Chinese Industrial Policy Compatible with its Environmental Ambitions, Sep 2021, 151-158.

à lire dans cette issue

voir toute la revue