Governing China’s Energy Sector to Achieve Carbon Neutrality

Philip Andrews-Speed

Senior Research Fellow at the Energy Studies Institute at the National University of SingaporeIssue

Issue #1Auteurs

Philip Andrews-Speed

21x29,7cm - 153 pages Issue #1, September 2021

China’s Ecological Power: Analysis, Critiques, and Perspectives

China accounts for nearly 30% of the world’s carbon dioxide (CO2) emissions from energy. The absolute quantity of emissions continued to rise at 2-3% per year during the decade to 2019 1 , and is estimated to have grown by 0.8% during the Covid-19 pandemic year of 2020 2 . This continuing increase of CO2 emissions is caused by the ongoing growth of the economy which in turn has been driving annual energy consumption rises of more than 4%. Fossil fuels are still dominant. In 2019, they provided for 85% of the primary energy supply, with coal accounting for 57%. Coal consumption did decline between 2013 and 2016, but it then rose a total of 3% between 2016 and 2019 3 . Energy consumption continued to rise during the 2020 pandemic, with that for coal increasing by an estimated 0.6%. 4 Demand for coal is likely to rise sharply in 2021 as the economy continues to rebound from the pandemic. 5 Consumption of both oil and natural gas continued to increase in 2020 and demand for both fuels is set to accelerate in 2021. 6

This, then, is the background against which China’s government will be drawing up their short- and medium-term plans for achieving President Xi Jinping’s pledge reach peak CO2 emissions before 2030 and to strive for carbon neutrality by 2060. A drastic reduction of CO2 emissions from the energy sector will be the most essential element, but not the only one. Other sources of emissions such as agriculture are also relevant, as are carbon sinks.

An increasing number of reports and papers are appearing that identify the specific challenges relating to the energy sector and the policy measures that should be implemented. 7 These include decarbonising electricity generation, electrifying end use sectors, switching to low-carbon fuels, sequestering CO2 and making demand sustainable. Technologies to be deployed at an accelerated rate include renewable energy sources, energy storage of different types, ultra-high voltage transmission, electric vehicles, hydrogen, and ‘smart’ technologies to manage electricity supply and demand. Further, the government aims to enhance the role of market forces in the energy sector, including through the national emissions trading scheme.

As is to be expected, central government ministries, local governments and state-owned enterprises are currently (as of March 2021) busy working out how to respond to the carbon-neutral challenge. The proposed 14th Five-Year Plan for National Economic and Social Development and Long-Range Objectives for 2030 was approved at the Fifth Plenum of the 19th CCP Central Committee in late October 2020 later by National People’s Congress in March 2021. 8 The document addresses the need for emissions to peak before 2030 but does not mention the issue of carbon neutrality by 2060. The Five-Year Plans for Energy and for others sectors are likely to be published later in 2021 or in 2022. Although these five-year plans may not explicitly address the 2060 objective, it is likely that the government will also publish medium- and long-term plans for different sectors over the next two or three years.

It is quite likely that CO2 emissions will peak by or before 2030, as long as the rate of economic growth remains relatively low. However, achieving carbon neutrality by 2060 is far more challenging and will provide a severe test to the way that China is governed. Whilst the Party-State has managed to enhance its control over the economy and society under the leadership of Xi Jinping, a number of questions remain in the context of the nation’s low-carbon transition. These include the existence of competing policy priorities across sectors, competing interests of different actors, the perpetual challenge of policy coordination, the way in which the energy sector is governed, and the need for technological and institutional innovation.

The aim of this paper is to identify the factors that will assist China’s transition to carbon neutrality and those that will constrain it by drawing on past experience in the energy sector. The next section shows how a combination of state and financial capacity has formed the basis of the country’s success to date in constraining the rise of carbon emissions. This is followed by an examination of those factors that have distorted or delayed energy policy implementation, with a focus of coordination challenges.

Factors that may assist the transition to carbon neutrality

China’s government is characterised by a formally centralised authority and strong state capacity. Together, these should assist the nation’s low-carbon transition. However, the capacity of the Party-State to design and implement policy has varied with time. The 1980s saw a high degree of decentralisation as part of economic policy. By the early 1990’s this decentralisation had resulted in a radical decline of the central government’s budget. The fiscal reforms of 1994 reversed this trend. 9 However, progressive economic reforms carried out during the 1990s reduced the influence of central government over the economy. This led to excessive economic growth, pervasive corruption and extensive environmental damage. 10

Under the leadership of President Xi Jinping, the central government has succeeded in increasing its control in many fields, including the economy. Economic growth has been allowed to slow to a “new normal”, state-owned enterprises remain central to government strategy and these enterprises have been subject to stricter fiscal and personnel controls. Within the energy sector, the state remains deeply involved. The production, transmission and transformation of energy within China is dominated by enterprises that are wholly or partially owned by the state at central or local government levels. The same applies to the highly energy-intensive energy industries such as steel, chemicals, cement and plate glass. Enterprises that are wholly or majority privately owned do play a significant role in some niches within the energy sector, especially those relating to new technologies such as renewable energy, batteries and electric vehicles. However, even these companies are likely to have close links with their local governments which, in many cases, have a significant shareholding in the company.

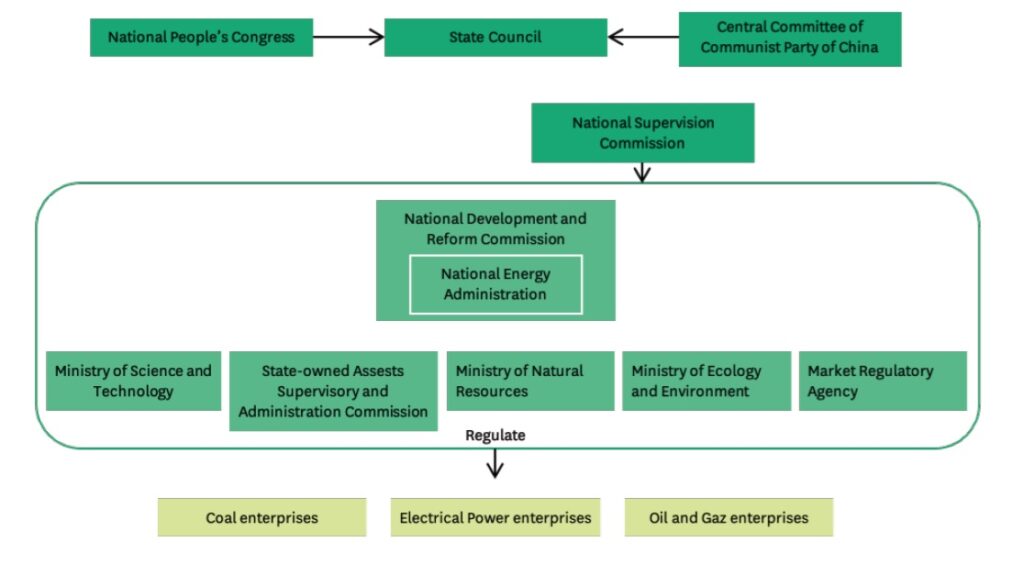

Within the government, the capacity to oversee the energy sector has also been growing. After the abolition of the short-lived Ministry of Energy in 1993, there was no clearly identifiable agency responsible for energy policy and regulation. Instead, these roles lay within departments of the State Planning Commission, now named the National Development and Reform Commission (NDRC). The government reforms of 2003 saw the creation of the National Energy Bureau within the NDRC. In 2008, this bureau was upgraded to be the National Energy Administration (NEA), also within the NDRC. Two years later, in 2010, a National Energy Commission was created, under the chairmanship of the Prime Minister, to oversee policy coordination across ministries. 11 The NDRC and other ministries have equivalents at all levels of local government. The NEA has six regional bureaus and 12 provincial offices that allow it to monitor and direct local developments in the energy sector. A reorganisation in 2018 led to the Ministry of Environment Protection being renamed the Ministry of Ecology and Environment (Fig.1) and taking over from the NDRC responsibility for implementing the national carbon market.

These structures along with the state ownership of most large enterprises along the energy supply chain have given the central government significant capacity to implement new energy policies over a relatively short timescales. The key to success has been the combination of administrative policy instruments and generous funding. Three historic examples are the energy efficiency campaign of 2005 to 2010, the programme to boost the deployment of renewable energy starting in 2009, and the measures to reduce air pollution from the power industry introduced in 2013.

When Wen Jiabao became Prime Minister in 2003, many Chinese provinces were suffering from a severe shortage of electricity resulting in systemic power outages. This was a result of soaring economic growth in the absence of new power generating capacity. In response, the government launched an energy efficiency campaign that aimed to reduce national energy intensity by 20% between 2005 and 2010. This involved setting energy intensity targets for local governments and state owned enterprises. A key component was the Top 1,000 Enterprises programme that focused on the large energy-intensive industries. Electricity tariffs for such industries were also raised. The outcome of these and other measures was that national energy intensity declined by an estimated 19.1% over this period, not far short of the target. 12

The development of wind and solar power in China dates back to the 1980s and 1990s respectively. However, it was only in 2005 that the central government made this a priority, in part on account of the power shortages just mentioned. The 2005 Renewable Energy Law introduced the concept of mandatory market share for renewable energy to any generating company with more than 5 GW of total capacity. Four years later, the 2009 Renewable Energy Law introduced feed-in-tariffs for the first time. Over the same period, the central government had been increasing funding for renewable energy research and development, and local governments were providing generous support in many forms for the manufacturers of wind power and solar photovoltaic (PV) equipment. 13 . The result was a surge in deployment of wind and solar PV infrastructure within China and growing exports of wind and solar power equipment. 14

Figure 1 • Simplified scheme showing the main energy-related organisations and enterprises at central government level after march 2018.

A further requirement for the success of this renewable energy was the development of direct current ultra-high voltage (DC UHV) transmission lines to carry the power from the remote northern and western regions of China to the demand centres in the centre and east of the country. Although the basic technology for UHV DC transmission had been developed in a number of countries, no commercial production of the equipment and no integrated UHV DC transmission system existed anywhere in the world at the beginning of the twenty-first century. It was the State Grid Corporation of China that was the first to commercialise the technology and to build an extensive network. 15

Air pollution from the use of coal in industry, heating and power generation has been a serious health problem in China for decades. Economic growth has led to a steady increase in the intensity of air pollution in the form of nitrous oxides, sulphur dioxide and particulate matter. Numerous attempts to constrain this rise met with limited success until 2006 when the levy for sulphur dioxide emissions was raised to a level above that of the cost of mitigation. This was accompanied by the installation of equipment to allow remote monitoring of emissions from all thermal power stations and the introduction of a subsidy to those plants using flue-gas desulphurisation equipment. These measures led to a decline in sulphur dioxide emissions. However, the economic stimulus that followed the global financial crisis of 2008 reversed this trend and by the winter of 2011/2012 the public outcry over the rising levels of air pollution threatened to undermine the legitimacy of the government. In 2013, an action plan of air pollution was issued. This was followed by other administrative and legal measures that together drove a sustained improvement of air quality, especially in the main cities. 16

An example more relevant to the future is the government’s policies for the development of battery technologies and electric vehicles. As was the case for renewable energy, support was directed along the full supply chain and involved both central and local governments.

Research into the technologies for new electric and hybrid vehicles began in the mid-1990s and from that time received progressively increasing support from government research and development funds. In response to the 2008 global financial crisis, twenty five cities were identified to push forward with electric vehicles. Subsidies from central and local government provided were directed at charging infrastructure and vehicle purchase, and covered both cars and city buses. By 2010 and 2011, the annual production of new energy vehicles had reached 7,000 and the national fleet exceeded 20,000. Of these, 25% were battery electric vehicles, the rest were hybrids. 17

The subsequent years saw central and local governments pursue an ambitious agenda for new energy vehicles, particularly for battery and plug-in hybrid electric vehicles. Quotas were set for manufacturers, subsidies were provided for vehicle purchase, and local governments preferentially licensed electric vehicles and, in some places, waived parking fees. 18 As a result, the annual sales of electric cars rose to 1.2 million in 2018. Sales remained at the same level in 2019 because the government had reduced the subsidies on vehicle purchase. 19 By mid-2020, annual sales of electric vehicles accounted for 4.4% of car sales. 20 December 2019 saw the government announce that electric cars should make up 25% of car sales by 2025, up from the 20% target set for 2025 in 2017. 21 This share could rise to 50% by 2035. 22

These and other examples show that China’s Party-State has the capacity, backed by ample funding, to take bold steps to address policy challenges and to take advantage of policy opportunities. The examples of renewable energy and electric vehicles reveal two additional features. First, that funding for research and development can be started decades before the appearance of commercial opportunity and, second, that strong synergies can be developed between industrial and energy policies.

A key to these and other policy successes in China continues to be the authority of the Communist Party and its deep involvement of the Party at all levels of government and in state-owned enterprises. At the top are the Central Leading Groups (sometimes referred to as Leading Small Groups) that are key coordinating bodies that exist in both the Party and the government. The former are more powerful. This power has been enhanced under the leadership of Xi Jinping for, since May 2018, he has headed at least five Party Leading Groups, in addition to his roles as Party General Secretary, President of China, and Chair of the two Central Military Commissions and of the National Security Committee. The most important of these Party Leading Groups for the economy is the Central Leading Group for Comprehensively Deepening Reforms, which was renamed as a Central Leading Committee in 2018.

The authority of the political leadership is transmitted downwards through three mechanisms: the nomenklatura system which controls staff appointments; the xitong system that allows the party to supervise activities across government agencies; and the dangzu groups that oversee the work of the Party Committees in all state-linked organisations. 23 More recently, the Party has taken steps to increase its oversight not only of state-owned enterprises, but also of private companies. 24

Despite the strong influence of the Communist Party, the multi-level and decentralised governance structure has brought two major advantages to China’s economic development. First, different localities have been able to pursue economic strategies that suit their conditions. Second, it has allowed the central government to carry out policy experiments in economic, administrative and political fields in a limited number of locations before deciding whether and how to roll out the policy across the country. 25

The growing awareness among citizens of the country’s environmental challenges has resulted in a dramatic increase in the number of environmental non-governmental organisations (NGOs) in China. They have become increasingly active in drawing attention to policy failures, arguing the case for certain policy measures and requesting information. However, they are rarely involved in policy deliberation and their influence remains weak. 26

Cautious experimentation has underpinned much of China’s economic success since the early 1980s. In the energy sector, this has involved the incremental liberalisation of producer and consumer tariffs for energy as well as the reform of state-owned energy enterprises. The steady corporatisation and commercialisation of these companies during the 1980s and 1990s was followed by a major restructuring in the period 1998-2002, accompanied by partial listing on domestic and foreign stock exchanges. However, these reforms did not succeed in introducing competition into the energy sector. Rather, the large centrally-owned, state-owned energy enterprises were able to increase their market power at the expense of private and local state-owned companies.

On his ascent to power, President Xi announced that he wanted to increase the role of market forces in the economy. The energy sector has been affected in three ways. First, 2015 saw the revival of plans to introduce competition across the full supply chain of electrical power, from generation through distribution to retail. 27 Second, in 2019, the oil and gas pipeline assets of the national oil companies were consolidated into a separate new company (PipeChina) 28 . Finally, the government launched the national carbon emission trading scheme in January 2021 after several years of local pilot schemes. 29 Whilst these market initiatives appear to promise improvements in economic efficiency and emission reduction, a range of institutional factors may constrain their effectiveness, as will be discussed in the next section.

Factors that may constrain the transition

The key challenge for China’s central government in any field of policy is coordination. Although legally a unitary state, formal authority lies at three main levels of government: central, provincial or municipal, and city or county. This structure combined with multiple ministries, powerful state-owned enterprises and huge geographic scale results in a complex matrix of governance that led to the creation of the term ‘fragmented authoritarianism’ 30 . Poor coordination is often the result. This may be caused by excessive haste in implementation that does not allow supply chains to react appropriately, or by excessive enforcement of new policies without due consideration for such issues as economic viability, technical standards or safety. In addition, local governments and state-owned enterprises retain the ability to ignore, undermine or distort central government policies to their own benefit. Such behaviours are often accompanied by false reporting, ‘feigned compliance’ and corruption, problems that date back to Imperial times. 31

This section illustrates the challenge of policy coordination by drawing on historical examples, before assessing the likely success of newly introduced market mechanisms in improving coordination. It concludes by identifying potential coordination difficulties between different policy fields.

Historical examples of poor coordination

Impetuous decision making

Impetuous policy making by central government can result in poor coordination in implementation and unintended consequences. A relatively recent example is the plan to convert the heating systems of up to four million households in northern China to natural gas or electricity in 2017 in order to reduce air pollution. At the same time, some 44,000 coal-fired boilers were to be scrapped and the sale of coal in the selected towns and villages banned. However, the construction of the necessary pipelines and storage tanks to support this dash for gas was an immense task with a cost of billions of RMB and could not be completed in the required time. 32

Although meeting with considerable success, the impetuous nature of this short-term gasification plan produced three undesirable consequences. First, although natural gas is more convenient and cleaner for families, it is more expensive than coal. Northern China is home to large numbers of low income families and the high price of natural gas led many households to reduce their use of heating. To alleviate such hardship, the government provided a certain quantity of gas at subsidised prices. Second, many coal-fired heating systems that were decommissioned had not been replaced by gas-fired ones by the onset of winter, leaving households without any heating at all. 33 Finally, the additional call on international markets for gas supplies had immediate effect on international markets, with Asian spot LNG prices reaching close to US$ 11 per million British Thermal Units (mmBTU) in January 2018, up from a low of less than US$6 per mmBTU in June 2017.

Local government resistance

Central government policy implementation often takes the form of vigorous campaigns, a style of governance in China that is not limited to the energy sector. 34 One such campaign in the late 1990s and early 2000’s was aimed at closing large numbers of small-scale township and village coal mines. During the 1980s and early 1990s these mines played a critical role in supplementing the output of large-scale, state-owned mines to ensure the nation’s growing economy was well supplied with energy. By the mid-1990s, some 80,000-100,000 of these small-scale mines accounted for nearly 50% of the country’s total coal production. But they were also the location of about 70% of the annual toll of coal mine 6,000 deaths in 1996. 35 A campaign to close large numbers of these mines was launched in 1998 on the grounds of safety, resource conservation and oversupply. This policy directly hit local economic interests. In response, many local governments systematically falsified their reports to higher authorities. Many mines that were reported as having been closed were either never closed or were closed and then quickly re-opened.

More recently, some local governments, often in collaboration with power companies, have taken active steps to protect or even promote coal-fired power generation in contravention of central government policy to increase the use of renewable energy. Such distortion of policy has taken two main forms. The first has involved favouring thermal power over renewable energy leading to substantial curtailment of wind and solar power. Average curtailment across the nation of wind energy rose from 8% in 2014 to 17% in 2016, with Gansu recording 40% that year 36 . The curtailment of solar power in 2016 also reached a peak, of 10% in this case. By 2019, curtailment of wind and solar power had declined to 4% and 2% respectively 37 .

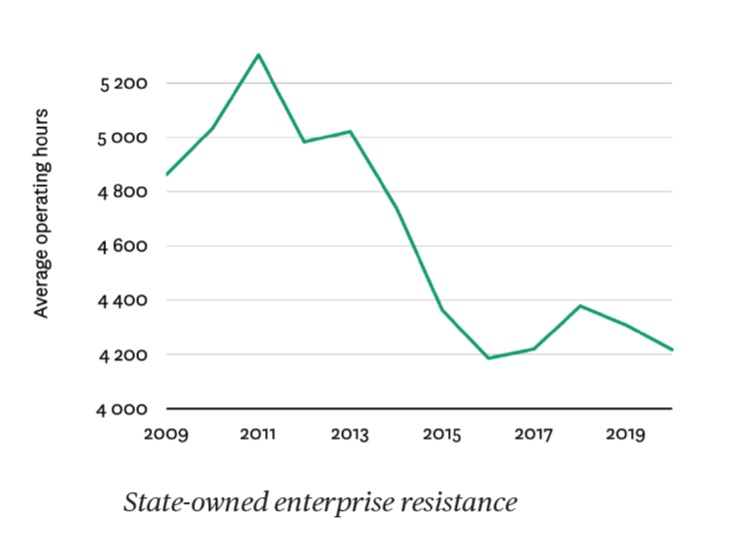

The sources of this high level of curtailment were numerous and included a number of purely technical issues. 38 However, the actions of local governments were also important. The number of hours of generation allocated to thermal plants was then still determined by local governments that created annual plans to be implemented by local system operators. Some local governments took advantage of this system to protect thermal power plants by dispatching thermal power in preference to renewable energy in direct contravention to the 2009 Renewable Energy Law as they employ more people and generate more local tax revenue than renewable energy installations. 39 Also, the thermal power stations lose out if the local grid operator dispatches renewable energy preferentially, for a reduction of operating hours raises the breakeven price. 40 Nevertheless, average annual operating hours for thermal power plants across China declined sharply after 2011 (Figure 2). 2016, annual averages have been consistently at or below 50%.

Local government support for coal-fired power has also been apparent in its encouragement for the construction of new generating plants in the absence of any obvious need in the form of an imminent supply-demand imbalance. In November 2014, the central government delegated the authority to approve the construction of new power plants to provincial governments. This led to permits being issued to 210 coal-fired plants with a total capacity of 165 GW in 2015 alone, mainly in coal-rich provinces. 41 Very few of these projects were approved by the central government. 42 Although the central government took back control over project approvals in April 2016, some 95 GW of new capacity was still under construction at the end of 2017. 43

Figure 2 • Average annual operating hours for China’s thermal power plants with capacity > 6 MW

State-owned energy enterprises also have the power to obstruct or ignore central government policies, and the national oil companies have been guilty of this on more than one occasion. Fuel quality is closely related to vehicle emissions, for the technology within the vehicle to reduce emissions relies on the concentration of pollutants in the fuel being below a certain level. Beijing banned the sale of leaded gasoline in 1997 and since then the central government has steadily raised the required standards of gasoline and diesel, especially for sulphur content. However, the actual quality of fuels sold has generally lagged behind the implementation of new standards, sometimes by several years. The main source of this weakness has been the reluctance of the national oil companies to upgrade their facilities. This has resulted not just in slow implementation but also in a high degree of variability across the country. 44

The legal system

It might be imagined that the legal system would form a route to address these abuses and distortions. However, despite reforms the overall approach to the law continues to bear a striking resemblance to that of Imperial times. The law is still seen as an instrument of government and the Party, to be deployed to retain power, maintain social order and promote economic development. 45

One innovation that should have supported the implementation of clean energy policies was a revision to the Environmental Protection Law that came into effect in January 2015 and for the first time permitted officially registered environmental NGOs to file public interest claims in the People’s Courts. 46 However, NGOs face a number of obstacles in filing cases in court. In addition to the requirement to be officially registered with the government, most Chinese environmental NGOs lack the funds and the expertise, face difficulties obtaining the necessary evidence, and encounter overly restrictive rules of standing. Moreover, they have no right to bring cases against public authorities. Only the procuratorates can do so. This is important because most violations have their roots in the failure of local governments to fulfil their obligations. Furthermore, Chinese law does not allow private parties to use the law to prevent other private parties causing damage before the damaging action takes place. 47

In 2016, the prominent environmental NGO, the Friends of Nature, filed cases against the grid companies of Gansu and Ningxia on the grounds that they had failed to purchase all the available wind and solar energy in their respective areas of jurisdiction. The claims were based on the environmental damage caused by the companies’ actions. Progress in the courts has been very slow and as of March 2021 neither case seems to have been resolved. 48

Likewise, as of 2018, no cases had been brought by either the NEA or renewable energy companies against the grid companies for failures to purchase renewable energy. The lack of action by the NEA relates to a range of technical and system management issues as well as the tension between these requirements and longstanding local practises. The Ministry of Ecology and Environment publically criticised the NEA and their local offices in January 2021 for failing to adequately implement a wide range of environmental policies. 49 In the case of the renewable energy companies, they face a large power differential between them and the vast monopoly that is the grid company. 50

Over-enthusiasm of local governments

Local governments are not always obstructive. Indeed, they can be over-enthusiastic in their implementation of central government policy, especially if it benefits economic activity within their jurisdictions. This has been evident in the manufacturing of equipment for wind and solar energy. The Renewable Energy Laws of 2005 and 2009 triggered a surge in deployment of wind and solar PV installations across China as well as in equipment exports. The central government and state-owned banks provided a range of supportive measures to equipment manufacturers through grants for research and development, low-cost loans, tax rebates and export credits. Local governments supplement these incentives by providing access to land and electricity supplies at subsidised prices. 51

This success in building a world leading renewable energy manufacturing industry was not achieved without cost. In addition to the substantial financial support described above, the rapid growth of the wind and solar PV manufacturing industries led to massive overcapacity in both cases. By 2011, 40% of the country’s wind power equipment manufacturing capacity was idle. 52 In 2012, it was reported that more than 2,000 enterprises in over 300 cities were developing solar PV manufacturing capacity. Capacity for producing PV panels had reached 20 times the national demand and twice that of global demand. 53 This excess of capacity arose from the over-enthusiastic support from local governments. Data from the U.S. investment agency, Maxim Group, showed that China’s top ten photovoltaic makers had accumulated a combined debt of 111 billion RMB by August 2012 leading the whole industry to the brink of bankruptcy. 54 This led to a period of industrial consolidation. The demand for higher standards of equipment is currently causing a second phase of consolidation among PV manufacturers, with the smaller players losing out. 55

Introducing market forces

To address these and other governance challenges, the government has been reinvigorating measures to enhance the role of market forces in the energy sector. The aims include aligning energy prices with market forces, improving the commercial performance of the state-owned energy companies and, in the case of oil and gas, boosting the production of domestic resources. 56 These efforts date back to the 1990s. The slow progress since then can be attributed to the influence of the state-owned energy companies on the policy-making process, natural caution of the part of leadership, and the ability of local governments and energy companies to undermine or distort the roll out of new market measures. The two most prominent initiatives are the introduction of competition to the electricity industry and the launch of a national carbon trading scheme.

Electricity market reform

The reforms to the electricity industry announced in 2015 proposed a number of measures: the promotion of competition in power generation by allowing generating companies to negotiate directly with large customers; the introduction of pilot spot markets; a system for setting and regulating transmission and distribution tariffs; opening investment in and operation of new distribution networks to companies other than the two existing grid enterprises; and the introduction of competition in electricity retail.

Whilst it is still early days in the reform process, a number of challenges have already appeared that reflect historical development China’s energy sector. 57 Local governments have been interfering with the market in different ways. They have been intervening in the bilateral transactions between generators and industrial consumers and not applying the agreed transmission and distribution tariffs. Local governments continue to undermine the key objective of enhancing inter-regional power trading, not least to reduce the curtailment of renewable energy 58 . Local agencies have also been distorting tenders for new distribution projects 59 as well as providing subsidies to loss-making power generators. 60

Further, the grid companies are able to use their strong market position to distort any emerging competition in distribution and retail. They have been demanding a controlling share of new distribution projects as a condition of providing access to the transmission infrastructure. 61 Likewise, the grid companies have set up nominally independent power retailers that draw on staff and information from the parent company, thus undermining fair competition with new entrants. 62

Carbon emissions trading scheme

In order to accelerate the decarbonisation of the energy sector, the country launched a national carbon emissions trading scheme in February 2021. Back in 2013, a number of pilot carbon emissions trading markets were initiated in different locations around the country. 63 The pilot carbon markets varied in design, but most suffered from several deficiencies: over allocation of allowances leading to low carbon prices, low market liquidity, weak institutional infrastructure, and inadequate monitoring, reporting and verification. 64 Of greater policy importance is the impact of the markets on carbon emissions. One study concluded that whilst the carbon emissions did decline in those industrial sub-sectors covered by the pilot schemes, this was due to a reduction of output rather than a reduction in emissions intensity. 65

In December 2017, the NDRC announced the long-awaited nationwide emissions trading scheme that would be implemented in phases. Initially, the national carbon market will cover only the power sector, including combined heat and power as well as the captive power plants of other industries. It will involve all units with annual emissions in excess of 26,000 tonnes of CO2 or energy consumption greater than 10,000 tonnes of coal equivalent. The power sector was chosen to be first as it has reasonably good data, relatively few points of emission, and is the largest producer of CO2 emissions in China.

As with other policy mechanism, issues relating to coordination and integrity are likely to characterise the national carbon market. For example, as provincial governments have responsibility for monitoring, verification and compliance, including for the accreditation of third-party verifiers, there is a risk that standards will vary across the country. 66 Such variability may be further enhanced as these local agencies have to pay the cost of verification. Also, emissions trading schemes do not operate in isolation and are affected by many other policies. A key challenge in China will be to achieve effective coordination between the national carbon trading market and policies for energy efficiency and renewable energy. The success of the national ETS is also highly dependent on how the electricity market reforms progress. 67 Without power sector reform, the national ETS is unlikely to reduce emissions in a cost-effective way. 68 Effective coordination between these two initiatives and with other policy instruments has been made more difficult by the allocation of responsibility for the national carbon market to the Ministry of Ecology and Environment, whilst the NDRC retains leadership for the power industry reforms.

With both of these new market mechanisms, electricity and emissions, there is a significant risk that trading may well expand but the effects on industry efficiency and emissions reduction may be drastically reduced by insufficient coordination and distorting behaviours. As discussed above, the legal system does not provide much scope for private actors to challenge the decisions and actions of local governments or large state-owned enterprises.

Coordination between different policies

The carbon neutrality pledge requires the rate of economic growth to remain relatively low – Xi Jinping’s “new normal”. However, the economic recovery plan implemented in response to the Covid-19 pandemic has triggered a surge of infrastructure development. This in turn caused coal consumption in 2020 to rise to levels above that of 2019, although the share of coal in the primary energy mix did decline. 69

This illustrates that the challenge for China’s leadership remains to keep economic growth high enough to maintain employment and social stability, but at the same time move from high-speed growth to high-quality growth by raising domestic consumption and reining in energy-intensive industries. However, the pace and energy-intensive nature of the economic recovery from Covid-19 70 combined with Xi’s proposal that GDP should double by 2035 71 will make it difficult for the planners to reconcile these trends with the low-carbon pledges, at least in the short-termthe aim of peaking carbon emissions by 2030.

Within energy agenda, a number of priorities expressed by the leadership in 2020 create potential tensions with priorities in other sectors. The government has repeatedly stated that the domestic production of energy of all types should increase and that dependence on oil and gas imports should decline. 72 This introduces two particular challenges. The first relates to industrial policy. The leadership has been encouraging state-owned enterprises of all types to become more commercially-oriented and has floated the possibility of creating a holding company like Singapore’s Temasek Holdings that would more clearly separate the government from the SOES and a reduction of their non-commercial obligations. 73 However, most of China’s remaining oil and gas reserves are likely to be of marginal commercial value, at best. These are not attractive targets for national oil companies that are supposed to shed their non-commercial obligations. Further, given the current leadership’s preferential support for the state-owned industries, it is far from clear that the energy markets will achieve their potential economic benefits, as discussed in the previous section.

The desire to constrain oil imports also conflicts with environmental policy. As road transport undergoes electrification, the future source of demand growth for oil will be from petrochemicals. As a result, Chinese companies are accelerating their construction of facilities to transform coal into chemicals. By 2018, coal was the source material for 16% of China’s petrochemicals, up from 3% in 2010. 74 These processes require large amounts of water and emit high levels of greenhouse gases. 75 To ameliorate the environmental impacts, companies will have to invest heavily in water recycling and carbon capture. Not only will this undermine the commerciality of the projects, but they will also require more energy, most probably in the form of coal.

Conclusion

President Xi Jinping’s pledge to strive for carbon neutrality by 2060 caught most observers by surprise. Modelling by Chinese and other analysts have shown that whilst this is technically possible, it will require radical changes across the whole economy, not just the energy sector. The recent record of achievements relating to energy efficiency and clean energy have shown that China can beat expectations when it comes to fulfilling ambitious tasks. The key to these successes lay in the combination of administrative instruments and generous financing deployed by the government to a sector dominated by state-owned enterprises. Nevertheless, policy coordination has continued to be a problem mainly due to the divergent interests of key actors. As a result, costs have been high, not all objectives have been met and unintended consequences have been numerous. Further, the current approach to governing the energy sector seems to be reaching the limits of its effectiveness. 76

Recognising this, the current leadership is pressing ahead by enhancing the role of market forces in the energy sector. In the absence of robust market regulation, local governments and state-owned enterprises are likely to retain the ability to distort these markets, at least to some degree. This will constrain the economic benefits to be gained from the energy markets as well as the environmental benefits from the carbon market.

The wider challenge facing the government is to balance the tensions between different policy priorities in a way that is supportive of the carbon neutrality pledge. The most profound of these tensions is between the need for economic growth to support employment and the rising living standards of a vast population and the requirement to keep economic growth relatively low and transition to a highly innovative, technologically-based economy. This challenge will be accentuated by the decline of the working age population 77 and the low level of education being received by the 70% of children that have rural residence permits. 78

Notes

- BP, BP Statistical Review of World Energy 2020, BP, 2020.

- Climate Action Tracker, China.

- BP, op. cit.

- The Business Times, “China’s Coal Consumption Share Falls to 56.8 % at End-2020”, march 2021.

- International Energy Agency, “Annual Changes in Coal Consumption by Type and Use in China, 2019-2021”.

- S&P Platts, “Commodities 2021 : China’s Economic Comeback to Add Sparkle to Oil Demand”, January 2021.

- For instance: The Energy Foundation, “China’s New Growth Pathway : From the 14th Five-Year Plan to Carbon Neutrality”, December 2020.

- B. Hofman, “China’s 14th Five-Year Plan : First Impressions”, East Asia Institute, National University of Singapore, EAI Commentary 26, March 2021.

- C. Wong, “Rebuilding Government for the 21st Century : Can China Incrementally Reform the Public Sector ? ”, The China Quarterly, vol. 200, 2009.

- B. Naughton, “The Chinese Economy.Transitions and Growth, Cambridge, Massachusetts ”, MIT Press, 2007 ; E. Economy, “The River Runs Black.The Environmental Challenge to China’s Future ”, Cornell University Press, 2004.

- P. Andrews-Speed and S. Zhang, “China as Global Clean Energy Champion : Lifting the Veil ”, Springer Nature, 2019.

- P. Andrews-Speed, “The Governance of Energy in China : Transition to a Low-Carbon Economy ”, Palgrave Macmillan, 2012.

- S. Zhang, P. Andrews-Speed, X. Zhao et Y. He, “Interactions Between Renewable Energy Policy and Renewable Energy Industrial Policy : A Critical Analysis of China’s Policy Approach to Renewable Energies”, Energy Policy, 2013.

- S. Zhang et al, “Interactions Between Renewable Energy Policy”, REN21,Renewables 2018 – Global Status Report, REN21, 2018.

- Y.-C. Xu, Sinews of Power, “Politics of the State Grid Corporation of China”, Oxford University Press, 2017.

- D. Seligsohn and A. Hsu, “How China’s 13th Five-Year Plan Addresses Energy and the Environment”, ChinaFile, 10 March 2016.

- H. Gong, M.Q. Wang, et H. Wang, “New Energy Vehicles in China : Policies, Demonstration, and Progress”, Mitigation and Adaptation Strategies for Global Change, 2013.

- V. Krusmann, “Mobility in 21st century China : Snapshots, Dynamics, and Future Perspectives”, GIZ, 2019.

- T. Gersdorf et al, “McKinsey Electric Vehicle Index : Europe Cushions a Global Plunge in EV sales”, McKinsey, July 2020.

- T. Gersdorf, R. Hensley, P. Hertzke et P. Schaufus, “Electric Mobility Demand After the Crisis : Why an Auto Slowdown Won’t Hurt EV Demand”, McKinsey, September 2020.

- Bloomberg News, “China Raises 2025 Electrified-Car Sales Target to About 25% , December 2019.

- Reuters Staff, “China’s NEV Sales to Account for 20% of New Car Sales by 2025, 50% by 2035”, Reuters, October 2020.

- Y. Zheng, “The Chinese Communist Party as Organizational Emperor. Culture, Reproduction and Transformation”, Routledge, 2010.

- S. Livingston, “The Chinese Communist Party Targets the Private Sector”, Center for Strategic & International Studies, 2020.

- S. Heilmann, “Economic Governance : Authoritarian Upgrading and Innovative Potential”, in J. Fewsmith (ed.), China Today, China Tomorrow. Domestic Politics, Economy, and Society, Rowman & Littlefield, 2010.

- J.Y.J Hsu et R. Hasmath, “Governing and Managing NGOs in China. An Introduction”, in R. Hasmath et J.Y.J. Hsu (eds.) NGO Governance and Management in China, Routledge, 2016. G. Chen, Politics of Renewable Energy in China, Edward Elgar, 2019.

- Central Committee of the Communist Party of China and the State Council, “Opinions on Further Deepening the Reform of the Power System”, document number 9, 2015.

- Downs et S. Yan, “Reform is in the Pipelines : PipeChina and the Restructuring of China’s Natural Gas Market”, Columbia/SIPA, Center on Global Energy Policy, Commentary, 2020.

- F. Jotzo et al, “China’s Emissions Trading Takes Steps Towards Big Ambitions”, Nature Climate Change, 2018.

- K.G. Lieberthal et M. Oksenberg, “Policy Making in China. Leaders, Structures and Processes”, Princeton University Press, 1988.

- L.W. Pye, “The Spirit of Chinese Politics”, Harvard University Press, 1992.

- D. Sandalow, A. Losz, et S. Yang. “Natural gas giant awaneks: China’s Quest for Blue Skies Shapes Global Markets”, Columbia/SIPA, Center on Global Energy Policy, Commentary, 2018.

- M. Lelyveld, “China’s Fuel Fiasco Leaves Citizens in the Cold”, Radio Free Asia, December 26th 2017.

- J.J. Kennedy, J. James et D. Chen, “State Capacity and Cadre Mobilization in China : The Elasticity of Policy Implementation”, Journal of Contemporary China, 2018.

- E. Thomson, The Chinese Coal Industry : An Economic History, RoutledgeCurzon, 2003 ; P. Andrews-Speed, Energy Policy and Regulation in the People’s Republic of China, Kluwer Law International, 2004.

- A. Hove, “Current Direction for Renewable Energy in China”, Oxford Institute for Energy Studies, Commentaire, June 2020.

- Annual data for wind and solar power curtailment in recent years is published on the website of the National Energy Administration.

- Z.-Y. Zhao, R.-D. Chang, et Y.-L. Chen, “What Hinder the Further Development of Wind Power in China ? – A Socio-Technical Barrier Study”, Energy Policy, 2016.

- Z.-Y. Zhao, S. Zhang, Y. Zou, et J. Yao. “To What Extent Does Wind Power Deployment Affect Vested Interests ? A Case Study of the Northeast China Grid”, Energy Policy, 2013.

- M.R. Davidson et al, “Modelling the Potential for Wind Energy Integration on China’s Coal-Heavy Electricity Grid”, Nature Energy, 2016.

- L. Myllyvyrta et X. Shen, “Burning Money. How China Could Squander Over One Trillion Yuan on Unneed Coal-Fired Capacity”, Greenpeace, 2016.

- M. Ren et al, “Why has China Overinvested in Coal Power ?”, The Energy Journal, 2021.

- C. Shearer et al. “Boom and Bust 2018. Tracking the Global Coal Plant Pipeline”, Coalswarm/Sierra Club/Greenpeace, March 2018.

- Y. Wu et al, “On-Road Vehicle Emissions and Their Control in China : A Review and Outlook”, Science of the Total Environment, 2017. ; J. Wang et al., “ Vehicle Emission and Atmospheric Pollution in China: Problems, Progress, and Prospects ”, PeerJ, 16 May 2019.

- C. Wang et N.H. Madson, Inside China’s Legal System, Chandos Publishing, 2013.

- R.Q. Zhang, et B. Meyer, “Public Interest Environmental Litigation in China”, Chinese Journal of Environmental Law, 2017.

- P. A. Barresi, “The role of law and the rule of law in China’s quest to build an ecological civilization”, Chinese Journal of Environmental Law, 2017.

- X. Wang, “Serious Wind and Solar Curtailment : Environment Protection Organization v. State Grid Gansu will Enter Trial”, January 2019 (in Chinese).

- Ministry of Ecology and Environment, “The Sixth Central Ecological and Environmental Protection Supervision Group Feedbacks the Inspection Situation to the National Energy Administration”, January 2021 (in Chinese).

- H. Zhang, “Prioritizing Access of Renewable Energy to the Grid in China : Regulatory Mechanisms and Challenges for Implementation” Chinese Journal of Environmental Law, 2019.

- P. Andrews-Speed et S. Zhang, “Renewable Energy Finance in China”, dans C.W. Donovan (ed.), Renewable Energy Finance, Imperial College Press, 2015.

- J. Li, et al. “China Wind Power Outlook 2012”, Greenpeace,2012 (in Chinese).

- D. Collins, “China’s Photovoltaic Industry on Brink of Bankruptcy”, August 2012.

- “China’s PV Industry is on the Verge of Bankruptcy”, Qianzhan, September 2012.

- M.Hall, “Chinese Polysilicon Makers Driving Industry’s Second Great Consolidation”, PV Magazine, October 2020.

- Central Committee of the Communist Party of China and the State Council,“Opinions on Further Deepening the Reform of the Power System”, Document Number 9, March 25th 2015 (in Chinese) ; ‘The Central Committee of the Communist Party of China and the State Council issued the “Several Opinions on Deepening the Reform of the Oil and Gas System” ’, Xinhua News Agency, May 21th 2017.

- C. Lin, “The Problem of Immature Market Trading Mechanism and Gaming of Local Interests Still Exist in the Four Years of ‘Electricity Reform’ ”, Sina, March 2019.

- P. Wang, “Opportunities and Challenges in the Construction of Power Spot Market”, China Power Enterprise, 2019, (in Chinese) ; L. Ma, “Analysis of the Development of the Power Industry and Prospects for the Reform of the Power System”, Polaris Transmission and Distribution Network, August 2019.

- P. Fan, R. Li, et P. Han, “What is the Solution to the Problem of Incremental Distribution Reform?”, China Energy News, January 2019 (in Chinese).

- Interview with a scholar in Beijing, October 2019.

- Y. Miao, Y. Liu, Z. Cao et M. Li, “Analysis on the Major Contradictions in the Reform of Incremental Distribution Network Business”, Journal of Shanghai University of Electric Power, June 2019, (in Chinese).

- South China Energy Regulation Office of National Energy Administration, “Report on Comprehensive Coordinated Supervision in 2018”, December 2018 (in Chinese).

- M. Duan et Z. Li, “Key Issues in Designing China’s National Carbon Emissions Trading System”, Economics of Energy and Environmental Policy, 2017.

- L. Xiong et al. “The Allowance Mechanism of China’s Carbon Trading Pilots : A Comparative Analysis with Schemes in EU and California”, Applied Energy, 2017. ; M. Duan, Z. Tian, Z. Zhao, et M. Li, “Interactions and Coordination between Carbon Emissions Trading and Other Direct Carbon Mitigation Policies in China”, Energy Research and Social Science, 2017.

- H. Zhang, M. Duan, et Z. Deng, “Have China’s Pilot Emissions Trading Schemes Promoted Carbon Emission Reductions ? – The Evidence from Industrial Sub-Sectors at the Provincial Level”, Journal of Cleaner Production, 2019.

- L.H. Goulder, R.D. Morgenstein, C. Munnings et J. Schreifels, “China’s National Carbon Dioxide Emission Trading System : An Introduction” Economics of Energy and Environmental Policy, 2017.

- F. Jotzo et al, “China’s Emissions Trading Takes Steps Towards Big Ambitions”, Nature Climate Change Commentary, 2018.

- F. Teng, F. Jotzo et X. Wang, “Interactions between Market Reform and a Carbon Price in China’s Power Sector”, Economics of Energy and Environmental Policy, 2017. ; M. Dupuy, “The Quiet Power Market Transformation Behind the New Carbon Market in China”, Energy Post, janvier 2018.

- Business Times, “China’s Coal Consumption Share Falls to 56.8% at End-2020”, March 2021.

- C. Shepherd et T. Hale, “China’s Economic Recovery Jeopardises Xi’s Climate Pledge”, Financial Times, November 2020.

- M. Pettis, “Xi’s Aim to Double China’s Economy is Fantasy”, Financial Times, November 2020.

- Xinhua Press Agency, “Full text : Energy in Chin’s New Era”, December 2020.

- “The State Council Has Approved the Temasek-Style Form of Chinese State-Owned Enterprises”, Caifu Hao, October 2020 (in Chinese).

- C. O’Reilly, “CTO and MTO Projects in China May Decelerate”, Hydrocarbon Engineering. May 2019.

- R. Liu, Z. Yang, et X. Qian, “China’s Risky Gamble on Coal Conversion”, China Environment Forum, January 2020.

- B. Lin, “China is a Renewable Energy Champion. But It’s Time for a New Approach”, World Economic Forum, Agenda, May 22th 2018.

- J.S. Black et A.J. Morrison, “Can China Avoid a Growth Crisis?”, Harvard Business Review, September-October 2019.

- S. Rozelle et N. Hell, Invisible China. How the Urban-Rural Divide Threatens China’s Rise, University of Chicago Press, 2020.

citer l'article

Philip Andrews-Speed, Governing China’s Energy Sector to Achieve Carbon Neutrality, Sep 2021, 56-66.

à lire dans cette issue

voir toute la revue