Issue

Issue #1Auteurs

Jean-Paul Maréchal

21x29,7cm - 153 pages Issue #1, September 2021

China’s Ecological Power: Analysis, Critiques, and Perspectives

On 4th December 2012, during Doha’s COP 18, an article summarising Beijing’s position regarding climate change was published in the online China Daily. It stated that “according to one wealthy country responsible for huge amounts of greenhouse gases emissions that has yet to sign on to make binding cuts, there is no rich-poor divide in emissions obligations. As usual, the United States has challenged the principle of ‘common but differentiated responsibilities’ during climate change talks in Doha, Qatar, saying that the future agreement on coping with climate change should be based on ‘real-world’ considerations and should not specify different responsibilities for rich and poor countries. But this really depends on what kind of real world the US is living in.” The author later went on to explain that “between developed and developing nations, there is a world of difference. That’s why equality can only be realized when different players bear obligations in line with their capacities.”, before reminding that “at the Durban Climate Conference in 2011, Xie Zhenhua, the head of the Chinese delegation, expressed the country’s willingness to discuss binding emissions cuts after 2020.” 1

Five years later, at the 2017 Davos Forum, two months after Donald Trump’s victory, Xi Jinping insisted that the countries who had signed the Paris Agreement should “stick” to the agreement “instead of walking away from it”. That same month, Xie Zhenhua stated that his country was “capable of taking a leadership role in combating global climate change”. 2 On October 18th of the same year, during the CCP’s 19th Congress, Xi Jinping declared that, “What we are doing today to build an ecological civilization will benefit generations of Chinese to come. We should have a strong commitment to socialist ecological civilization and work to develop a new model of modernization with humans developing in harmony with nature. Our generation must do its share to protect the environment.” 3

In the meantime, Xi Jinping and Barack Obama had met in Beijing in November 2014 at the Asia-Pacific Economic Cooperation (APEC) Forum, during which the two presidents issued a joint statement on the fight against climate change. The Chinese president stated China’s intent to reach peak CO2 emissions around 2030 and to make every effort to achieve it before then. The US president had claimed that by 2025, the US would reduce its emissions by 25 % to 28 % from 2005 levels and that it would do its utmost to reach 28 %. A year later, all of this would be included in the Paris Agreement (2015).

Are the Chinese really changing direction? And how much credit should be given to Beijing’s (relatively recent) commitments? Among the many reasons that could explain the Chinese government’s change of attitude towards the fight against global warming, there are three that seem particularly important to us. They are, respectively, socio-environmental (1), economic (2) and diplomatic (3) the problems observed and the measures taken in each of these areas tend to reinforce one another. Hence the commitments that were made, especially at an international level, whose truly binding nature is questionable (4).

Socio-environmental reasons

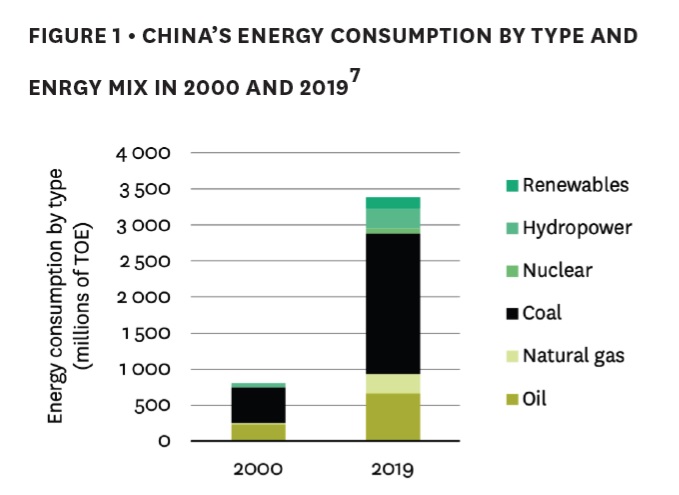

Since the beginning of the reforms initiated in 1978, China has experienced dramatic economic growth. In fact, between 1980 and 2017, China’s GDP (including Hong Kong) rose from 395.7 to 10,441.4 billion dollars (2010) which represents a 26.4-fold increase. In constant yuan terms, it was multiplied by 28.9 4 . At the same time, GDP per capita increased 18.6-fold, rising from $401.10 to $7,491.30. Such an economic boom over such a long period of time was only possible because of energy consumption that is without precedent in the country’s economic history. Total primary energy demand went from 602 million tons of oil equivalent in 1980 to 3,077 million in 2017 — a little more than a 5-fold increase 5 . Fossil fuels — and especially coal — have been, and still are, heavily used to reach such levels of production (Figure 1).

This has led to an explosion in Chinese CO2 emissions from 789.4 million tons in 1971, to 2.12 billion in 1990, and 9.3 billion in 2017 6 . Such levels of emissions have brought about both a deterioration in air quality – and thus strong public discontent – and a growing awareness from the authorities regarding the dangers of climate change.

Figure 1 • China’s energy consumption by type and enrgy mix in 2000 and 2019 7

The first phenomenon – the degradation of air quality – is often summarised with a neologism, “airpocalypse”, which appeared in the 2000s to refer to the record levels of pollution observed in major Chinese cities. The main pollutants affecting the well-being of city residents are nitrogen oxides (NOx), sulphur dioxide (SO2), carbon monoxide (CO), heavy metals (arsenic, cadmium, etc.) present in coal combustion ashes, etc. In 2009, 19 out of the 36 cities in the world with the highest levels of pollution from particles with 10 micrometers or less in diameter (PM10) were in China — including Xian, Tianjin, Harbin and Shanghai. In early 2013, for instance, a spike in pollution hit Beijing for three days 8 . On January 11th, the levels of PM 2.5 in some parts of the city reached 993 micrograms per cubic metre, i.e. approximately 40 times more that the WHO standard, which estimates that being exposed to levels above 25 micrograms for more than three days per year is harmful to health 9 . These pollution levels generated such strong frustration that the authorities responded to public pressure by finally agreeing to publish air quality data for Beijing in 2012 and for 74 other cities the following year 10 . The fact that the Chinese authorities asked the meteorological station at the American Embassy in Beijing to stop publishing pollution alerts in 2012 because the practice was deemed to be an interference in Chinese domestic politics, is very revealing of the extent of the issues at stake 11 ! The same year, an MIT study estimated the cost of air pollution in China at $112 billion (at their 1997 value), whereas it was $22 billion in 1975 12 .

For many years, it was believed that outdoor air pollution in China caused between 350,000 and 400,000 deaths per year 13 . However, a 2015 study — based on Chinese measurements conducted at 1,500 sites and including PM 2.5 (particles smaller than 2.5 microns in diameter, and more dangerous than PM 10) — found that air pollution actually causes 1.6 million deaths per year, i.e. 17% of all deaths in the country. 83 % of Chinese people are exposed to levels of air pollution that, in the United States, are considered hazardous to health or hazardous to frail people 14 . In February 2021, a study published on the website Environmental Research estimated that PM2.5 pollution from fossil fuel combustion alone will likely cause 3.9 million premature deaths 15 .

In the long run, such a situation risks eroding the legitimacy of the Party, which now largely, if not solely, rests on its capacity to improve the population’s well-being. Indeed, since the events of 1989, it is as if the government had “exchanged” the absence of democratic reforms with the promise to improve the living conditions of Chinese citizens. However, the massive deterioration of the environment seriously compromises the fulfillment of such a promise. And so, during the 2000s, as pollution problems increased, causing public frustration 16 , the government realized that it was necessary to take a certain number of measures. One of the most significant moments in this evolution occurred in 2006 when Hu Jintao called for the construction of a “harmonious society”, i.e. a form of development that would take social inequalities and environmental damage into account. This priority was announced before the 17th CCP Congress — which was held in 2007 and confirmed Hu Jintao for a second term as the country’s leader — and was finally written into the Party’s constitution as “scientific development”. A year later, in 2008, the Environmental Protection Bureau (created in 1974) became the Ministry of Environmental Protection; it holds the 16th official rank out of the 25 ministries and commissions of the State Council. Despite this shift, the environment continues to deteriorate.

It is especially because of the increasing number of pollution peaks in major cities that the current leaders, which came to power in 2012 during the 18th Congress, launched a series of ambitious initiatives 17 . It is in such a context that in September 2013 the government introduced an action plan to control and prevent air pollution. In 2015, the (National) Environment Act, which dates back to 1979 and was already revised in 1989, was thoroughly revised once again. In addition, the last three five-year plans (the 13th plan covered 2016-2020) contained increasingly stringent environmental targets.

Beyond social frustration caused by the “airpocalypse” 18 , the Chinese government is also gradually coming to the realization of the threats that rising temperatures pose to the country: endangerment of coastal cities (Shanghai, Hong Kong, etc.), increase in the number of extreme weather phenomena, multiplication and aggravation of droughts and floods, desertification (in a country that already has to feed nearly 20 % of the world’s population with only 7 % of the world’s arable land resources), not to mention the disruption of air traffic (during the most severe episodes), the closing of schools, and the limitation of outdoor activities 19 .

Climate change may, for instance, exacerbate existing water stress. Even though China holds 20 % of the world’s water reserves, its volume per capita is probably only 2,000 cubic metres per year (compared to a world average of 6,200). This can be explained by the poor distribution of water. The north of the country (north of the Yangtze), where two-thirds of farmable land and 40 % of the population are located and which generates half of the national GDP, holds only 20 % of the country’s water. Climate change is likely to reduce rainfall in this region, while at the same time, groundwater is being depleted 20 . 440 out of China’s 660 major cities (i.e. 353 million inhabitants) are suffering from a severe water shortage. There is also a qualitative dimension to this quantitative problem. The water supply in half of Chinese cities does not meet WHO standards 21 . In a press conference held in Beijing in February 2012, Hu Siyi, the vice-minister of the Ministry of Water Resources, revealed that 40 % of rivers were seriously polluted, and 20 % of rivers were so toxic that humans should not even come into contact with their water. Two-thirds of Chinese cities are experiencing water supply stress, while 300 million people in rural areas have no access to clean water 22 . Groundwater quality has also deteriorated: 60% of groundwater in the north of the country is polluted to a level that makes it unsafe for drinking 23 .

In June 2007, China published its first long-term plan on climate change. A 2011 report by the State Oceanic Administration warned that sea levels bordering the country had risen by 2.65 millimetres per year over the past three decades, and that average atmospheric and marine temperatures had risen by 0.4 and 0.6°C respectively over the past ten years. According to the State Oceanic Administration, sea level rise is a “gradual” marine disaster that could “worsen the consequences of storms and coastal erosion” 24 . In 2015, the head of the government’s meteorological service warned that climate change posed “serious threats” to rivers, food supply, infrastructure, etc. 25

Of course, the deterioration of air quality and greenhouse gas emissions are partly independent phenomena. Nevertheless, given the share of fossil fuels in China’s energy mix, it is obvious that reducing the share of coal and oil will automatically decrease the emissions of microparticles, black carbon, etc., which are detrimental to the quality of life of millions of Chinese people 26 .

Economic reasons

The second reason for China’s change in direction is probably to be found in the fantastic potential in terms of exports and influence that “green” or, more precisely, “low-carbon” technologies, represent. This is how, over the last twenty years, China has become the world’s leading producer of LEDs, wind turbines, solar panels, electric cars batteries, electric cars, and more.

Behind all of these “success stories” is of course the talent of Chinese researchers, company directors and their engineers, technicians, and workers — but also the “visible hand” of the Chinese government. A study conducted by the European Union Chamber of Commerce in China highlights that within the framework of the China Manufacturing 2025 strategic plan launched by Beijing in May 2015 (on which the regime no longer communicates much however), the financial support for Chinese companies announced by both the central and local governments will amount to several hundred billion euros. Among the sectors targeted by this initiative are electric vehicles, electric equipment, and robots 27 . In comparison, the recovery plan approved by France to help the aeronautical sector, a victim of the crisis caused by the Covid-19 pandemic, amounts to some twenty billion euros. Of this, “only” 1.5 billion euros are destined to “decarbonized” aviation 28 .

When it comes to energy production, there is massive investment. In January 2017, the National Energy Administration of China announced 360 billion dollars of investments in new energy production capacities between 2017 and 2020: 144 billion for solar energy, 100 billion for wind power, 70 billion for hydroelectricity 29 , etc. Meanwhile, the International Energy Agency estimated that the Chinese public and private sectors would invest more than 6 trillion dollars in low-carbon energy production technologies between now and 2040 30 . As a comparison, in 2015, Chinese companies had invested more than $100 billion in renewable energy, while American firms had spent only $44 billion. 31

We can see the results. Throughout its territory, China now accounts for a third of the world’s wind power and a quarter of the world’s photovoltaic power capacity. Chinese companies in these sectors benefit from a domestic market whose size allows them to achieve significant economies of scale and thus extremely low production costs. The same could be said for the manufacturing of lithium batteries for cars or hydroelectricity. According to the International Energy Agency, four of the top ten wind turbine manufacturers in the world and six of the top ten solar panel producers are Chinese 32 .

The automobile sector is not lagging behind either. The purchase of electric vehicles has been massively aided both directly ($8.4 billion in government aid in 2015, i.e. ten times more than in the United States) and indirectly (tax incentives according to the type of vehicle) 33 . In view of its success, this costly system was brought to an end in 2018. Indeed, as early as 2015, sales of electric cars (annual and cumulative) in China exceeded those made in the US 34 . Between 2011 and 2017, the number of electric cars sold in China jumped from 4,200 to 601,700, while worldwide sales rose from 49,600 to 1,202,700.

Beyond these essentially economic reasons, the development of green technologies in China also serves some more geopolitical objectives.

Since the fall of 2019, the United States has increased its oil production to the point of becoming a net exporter. China currently imports 70% of its oil and this figure could rise to 80% by 2030 35 . The country could thus find itself much more exposed than the US economy to the consequences of possible unrest in a Middle Eastern region where Washington now has fewer direct interests.

By strengthening the country’s energy security, the massive development of green technologies in China makes it possible to limit (at least partially) these risks. It could also counter the influence of the United States by offering low-carbon solutions to foreign countries, enabling them to reduce both their oil consumption and their CO2 emissions.

As summarised by Amy Myers Jaffe, if Beijing’s strategy is successful, it will make a valuable contribution to the global fight against climate change and help China “to replace the United States as the most important player in many regional alliances and trading relationships”. In other words, China “hopes that demand for clean energy technology from countries looking to reduce their carbon emissions will create jobs for Chinese workers and strong relationships between foreign capitals and Beijing, much as oil sales linked the Soviet Union and the Middle East after World War II. That means that, in the future, when the United States tries to sell its liquefied natural gas to countries in Asia and Europe, it may find itself competing not so much with Russian gas as with Chinese solar panels and batteries.” In the middle of the ongoing transformation of the energy market, China could thus obtain an edge in the rivalry between “electro-states” and “petro-states” 36 .

However, a country’s influence also depends on its capacity to entice and on its ability to conduct effective “public diplomacy”, which is undoubtedly one of the reasons why Beijing played a part in the Paris agreement.

Public diplomacy factors

Beijing is using the climate issue to try and improve its international image which tends to be marred by the regime’s evolution.

Indeed, between the implementation of the “social credit” system 37 (and the electronic surveillance of citizens that is a part of it 38 ), the detention of a million Uyghurs 39 , the takeover of Hong Kong in violation of the commitments made at the time of its retrocession, the hawkish declarations with regard to Taiwan 40 , the expansionism in the South China Sea 41 , the request for censorship towards Cambridge University Press or Springer 42 , the inclusion in 2017 of “Xi Jinping’s vision, of a socialism with Chinese characteristics for a new era” in the Party charter 43 — along with the creation of an institute dedicated to the interpretation and dissemination of this vision 44 —, or the modification of the constitution in 2018 which now allows Xi Jinping to run for as many presidential terms as he wishes, China definitely lacks some “soft power”, to quote the phrase coined by Joseph Nye thirty years ago.

In an argument reminiscent of Antonio Gramsci’s thoughts on hegemony in his “Quaderni” 45 , Joseph Nye writes that “if a state can make its power seem legitimate in the eyes of others, it will encounter less resistance to its wishes. If its culture and ideology are attractive, others will more willingly follow. If it can establish international norms consistent with its society, it is less likely to have to change. If it can support institutions that make other states wish to channel or limit their activities in ways the dominant state prefers, it may be spared the costly exercise of coercive or hard power.” 46 Simply put, “soft power is the power of attraction”. 47

Aware of this attractiveness deficit, Hu Jintao said in 2006: “The enhancement of China’s international status and international influence must be reflected in both hard power, including the economy, science and technology, and national defence power, and in soft power, such as culture”. 48 Six years later, Xi Jinping launched the idea of the “Chinese Dream”; the dream of a moderately prosperous society, of a newfound national pride, of the advent of a spiritual socialist civilisation. Political communicators are never short of a new slogan, and the “Chinese Solution” emerged in 2015, a formula used for the first time by Xi Jinping during a New Year’s message on 21 December 2015 and repeated notably during the 95th anniversary of the founding of the Chinese Communist Party in July 2016. On that occasion, the President claimed that the Chinese people were “fully confident that they can provide a Chinese Solution to humanity’s search for better social institutions”. 49

Given a pattern of human rights violations at home, contributing to the implementation of the Paris Agreement can only serve China’s image abroad. Thus, in January 2017, just after Donald Trump’s victory and Washington’s predictable withdrawal from the Paris Agreement, Xi Jinping insisted at the Davos Forum that the signatory countries of the Paris Agreement should “stick” to the agreement “instead of walking away from it”.

While the term “Chinese Solution” hasn’t clearly been defined, it nevertheless says a lot about the Middle Kingdom’s determination to exercise leadership over world affairs and its confidence in doing so. The discourse on soft power can then serve to conceal the power relations that Beijing, like any actual or potential hegemon, is trying to establish in international relations. As Philip Golub showed, Chinese speeches on soft power, like their American counterparts, conceal and minimise the power relations present in international politics. 50

Binding commitments?

The reasons we have just outlined were translated into commitments in the Paris Agreement 51 . In its “National Determined Contribution” — the commitments made in December 2015 — Beijing promised to cap its CO2 emissions around 2030 and to do its utmost to do so before then, to reduce its CO2 emissions per GDP unit (i.e. carbon intensity) by 60-65% by 2030 compared to 2005 levels, to increase the share of non-fossil fuels in primary energy consumption to around 20% and, finally, to increase its forest stock volume by around 4.5 billion cubic metres compared to 2005 levels. These objectives, especially the first three, are potentially achievable within the announced timeframe. There are three main reasons for this.

The first is obviously the slowdown in Chinese economic growth which, in the context of a “new normal” announced in the mid-2010s 52 , is now just over 6%.

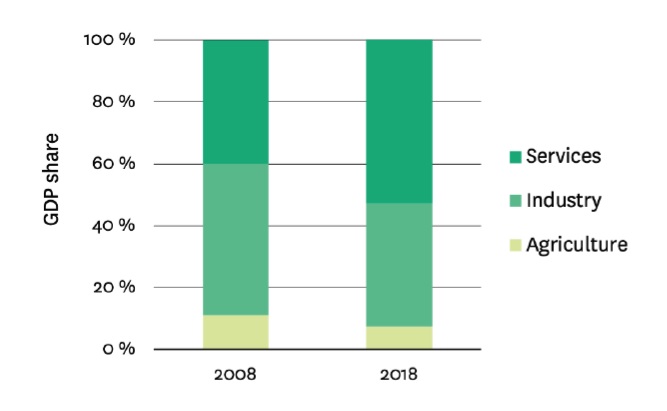

The second is to be found in the growth of the country’s service sector. Over the past ten years, the Chinese economy has become a service economy (Figure 2); services increased from 40% to almost 53% of GDP, while industry lost 10 percentage points, falling from 49% to 39.9%. However, a study conducted from 1992 to 2012 shows that the average carbon intensity of services in China is 67.5 tonnes of CO2 per million yuan of GDP, while that of industry is 838.7 tonnes, or 12.4 times higher 53 .

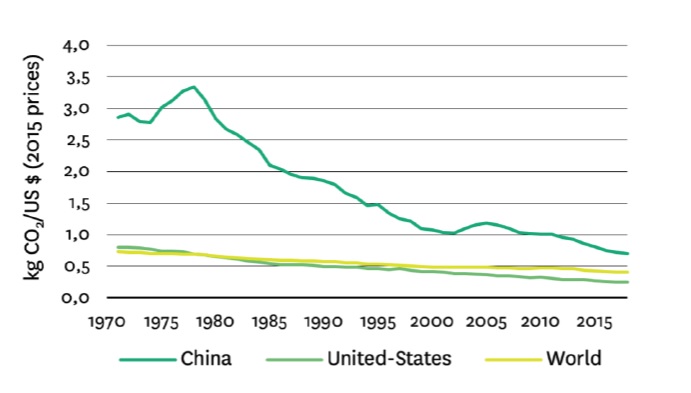

As for the commitment to improve the carbon intensity of the economy from 60 to 65%, this too will be achieved for a simple reason. This indicator has been improving everywhere for several decades under the combined effect of the improved efficiency of devices that use fossil fuels and the evolution of the energy mix in favour of technologies that do not directly emit CO2 such as nuclear, wind, photovoltaic, hydroelectricity, etc. As Jacques Percebois and Jean-Pierre Hansen have shown, the improvement of an economy’s carbon intensity is closely linked to that of its energy intensity. However, the improvement in a country’s energy intensity is a phenomenon that can be found in all industrialised countries and this occurred long before concerns about climate change emerged 54 55 . It is true that China’s carbon intensity has already decreased significantly (Figure 3), but there is still significant room for improvement. Indeed, CO2 emissions per dollar of wealth created are still higher in China today (990 grams) than in the US in 1971 (870 grams). As for energy intensity, over the past 40 years, as seen above, China’s GDP has multiplied by 26 and its energy consumption by “only” 5.

Figure 2 • Evolution of china’s gdp by sectors 56

If the 2015 commitments could be met — even if we must always be cautious when it comes to forecasting (especially when it comes to China!) — what about the new ones? 57 The presentation of the new five-year plan at the beginning of last March did not provide any particularly convincing elements.

At the December 2020 summit held (by videoconference) to mark the 5-year anniversary of the Paris Agreement, and where countries were to make announcements increasing their climate commitments, China committed itself to capping its CO2 emissions “before” 2030 and no longer “around” 2030, to reduce its carbon intensity by “more than 65%” instead of “between 60 and 65%” and to increase its share of renewable energy to 25% of primary energy by 2030 (it is already at almost 13% as can be seen in Figure 1). This progress is not spectacular, and so these promises will be kept 58 .

Figure 3 • CO2 emissions /GDP at current exchange rate 59

In addition, an announcement was made on September 22nd that carbon neutrality would be achieved by 2060. It is of course difficult to give an opinion on such a distant deadline, but certain simulations prompt caution. For example, projections by the International Energy Agency show that if Beijing were to add the measures announced in the 13th plan to the policies already implemented — what the IEA calls a “new policies” scenario — total energy consumption would rise from 3 billion tonnes of oil equivalent in 2016 to almost 3.8 billion in 2040, i.e. an annual 1% increase. In other words, despite the considerable efforts made, China will still be the world’s largest consumer of coal in 2040 and the largest oil consumer in 2030 60 . It is thus difficult to imagine that it will be carbon neutral 20 years later.

Beijing did not specify whether its new targets were for domestic emissions or also includes their investment in coal plants abroad, particularly along the New Silk Road. This is not a rhetorical question when you consider that in the first half of 2020, China built 60% of the world’s new coal plants 61 . Chinese financing of coal plants abroad is expected to lead to an increase in generating capacity of 74 GW between 2000 and 2033. It is estimated that Chinese-funded coal plants outside the country already account for annual emissions of 314 million tonnes of CO2, i.e. slightly less than Polish emissions. It is worth pointing out that many of the plants sold abroad use outdated technology and could no longer be installed in China where standards have become much stricter! 62

It is true that the new power plants built in China are either “supercritical” or “ultrasupercritical” and that, in 2018, they represent respectively 19 and 25% of the national network. In comparison, the United States has only one ultrasupercritical plant at the moment. The results are clear: “The deployment of these technologies has significantly reduced coal consumption, and therefore CO2 emissions, per unit of electricity produced: in 2006, more than 340 grams of coal were necessary to produce one kWh, whereas in 2018, it took an average of 308 grams. In the 100 most efficient power plants, coal consumption is even down to 286 g/kWh.” 63 Using this kind of power plant is a result of the acknowledgement that diversifying the energy mix will probably not be sufficient to reduce polluting emissions and CO2 discharges as quickly as desired.

However, some of the information remains worrying. For instance, a report published in September 2018 highlighted that a total of 259 GW of coal powered generation capacity was under construction in China, an amount equivalent to the production capacity of all of the US’s coal plants (266 GW)! This 259 GW is added to to the 993 GW already in place and jeopardises Beijing’s target of not exceeding 1,100 GW of coal power generation over the course of the 13th Plan 64 . A year later, another report showed that between 2018 and June 2019, China had increased its coal power generation capacity by 42.9 GW while the rest of the world had reduced it by 8.1. 65

Conclusion

Finally, it is quite clear that China’s evolving position highlighted at the beginning of this article is a fairly accurate reflection of Beijing’s changing interests.

These are now embodied in quantified commitments based solely on intensity indicators (whereas the EU has adopted quantitative targets since the Kyoto Protocol), unquantified long-term promises, a reference year in the future, as well as an intense international communication on the issue of the climate emergency.

This does not mean, however, that China is not making many successful efforts. For instance, air quality is improving in Chinese cities. The concentration of PM2.5 in China is said to have fallen by 43.7 % between 2012 and 2018, which would have reduced the annual number of premature deaths from 3.9 to 2.4 million. It is true that, as it is the source of 28 % of global CO2 emissions, China can influence the earth’s climate, and therefore the weather conditions in its own territory.

Joe Biden’s election is going to change the structure of the Chinese-American duopoly on climate. This may be for the better if collective leadership emerges. But caution is needed. As Paul Valéry wrote in 1935, we are living in an era where “any forecast becomes […] a possibility for error”.

Notes

- “Welcome to real world of climate change”, China Daily, 2012.

- “No cooling”, The Economist, 2017.

- Full report of Xi Jinping at the 19th National CCP Congress.

- World Bank, OCDE, “PIB par habitants (unités de devises locales constantes)”, consulted on January, 26th 2021.

- IEA, “CO2 Emissions From Fuel Combustion. Highlights ”, 2019.

- Ibid.

- Sources: BP, “BP Statistical Review of World Energy”, 2002 and 2020. Renewables = solar + wind.

- The Economist, “Pocket World in Figures. 2013”, Profile Books, 2012.

- B. Pedroletti, H. Thibault, “Pékin émerge du cauchemar de la pollution”, Le Monde, 2013.

- H. Thibault, “Les villes de Chine contraintes de rendre leur air transparent”, Le Monde, 2013.

- M-C. Bergère, “Chine. Le nouveau capitalisme d’État”, Fayard, 2013.

- K. Matus et al., “Health damages from air pollution in China”, Global Environmental Change, n° 22, 2012.

- B. Vermander, “Chine brune ou Chine verte ? Les dilemmes de l’État-parti”, Les Presses de Sciences Po, 2007.

- R. A. Rohde, R. A. Muller, “Air Pollution in China: Mapping of Concentrations and Sources”, 2015.

- K. Vohra et al., “Global mortality from outdoor fine particle pollution generated by fossil fuel combustion: Results from GEOS-Chem”, Environmental research, 2021.

- N. Salmon, Chapter 4 : “Analyse d’une mobilisation environnementale : inquiétudes sanitaires et enjeux politiques liés à la pollution de l’air par les microparticules”, in J-P. Maréchal (éd.), La Chine face au mur de l’environnement ?, CNRS Editions, 2017.

- J-F. Huchet, La crise environnementale en Chine, Les Presses de Sciences Po, 2016.

- In 2005, over the recorded 87,000 “mass incidents”, 51,000 (58%) were linked to pollution issues. Even if this data is officially not published anymore since 2010, the number of incidents is estimated to 150,000 per year. See B. Pedroletti et F. Lemaître, “Chine 70 ans de règne de l’État-parti”, Le Monde, 2019. Some sources estimate the number to 180 000. See F. Godement, Que veut la Chine ?, Odile Jacob, 2012 and J-P. Maréchal, Chine/USA. Le climat en jeu, Choiseul, 2011.

- J-F. Huchet, op. cit.

- J-M. Chaumet, Chapter 12 : “L’impact des problèmes environnementaux agricoles sur le commerce et les relations internationales chinoises”, in J-P. Maréchal (éd.), La Chine face au mur de l’environnement ?, op. cit.

- J-F. Huchet, op. cit.

- Y. Jian, “China’s River Pollution ‘a Threat to People’s Lives’ ”, Shanghai Daily, 2012.

- J-F. Huchet, op. cit.

- H. Thibault, “La Chine s’inquiète de la montée du niveau de la mer sur son littoral”, Le Monde, 2011.

- The Economist, “No Cooling”, 2017.

- [editor’s note] See the article of S. Monjon and L. Boudinet titled “État de l’environnement en Chine : quelles évolutions ces dernières années ?”, page 126 for the current state of play of the environment in China.

- European Union Chamber of Commerce in China, “China Manufacturing 2025. Putting Industrial Policy Ahead of Market Forces”, 2017.

- J-P. Maréchal, “Le décollage de l’aéronautique ‘vert’, effet ‘secondaire’ de la crise de la Covid-19 ?”, Choiseul Magazine, 2020.

- IRENA, “Renewable Energy and Jobs – Annual Review 2017”, 2017.

- A. Myer Jaffe, “Green Giant. Renewable Energy and Chinese Power” Foreign Affairs, 2018.

- S. Roger, “Trump brouille les négociations climatiques”, Le Monde, 2017.

- “The East is Green”, The Economist, 2018.

- France Stratégie, “L’avenir de la voiture électrique se joue-t-il en Chine ?”, La Note d’analyse n° 70, 2018.

- A.Myer Jaffe, op. cit.

- Ibid.

- “Petrostate v electrostate”, The Economist, 2020.

- “Creating a digital totalitarian state”, The Economist, 2016 ; “Keeping tabs”, The Economist, 2019.

- B. Pedroletti, “En Chine, le fichage high-tech des citoyens”, Le Monde, 2018.

- Monde chinois nouvelle Asie, L’envers des routes de la soie : analyser la répression en région ouïghoure, 2020.

- “Dire strait”, The Economist, 2019.

- Y. Roche, “La stratégie de Pékin en mer de Chine du Sud : entre séduction et coups de force”, Diplomatie, Les grands dossiers, Géopolitique de la Chine, 2018.

- “At the sharp end”, The Economist, 2019.

- B. Pedroletti, “À Pékin, le sacre de Xi Jinping”, Le Monde, 2017.

- “Mind-boggling”, The Economist, 2018.

- For Antonio Gramsci (1891-1937), a policy led by a given social group can be considered as hegemonic if the policy is consented to by the dominated classes. Initially created to analyze the workings of internal State policies, in particular Italy since the Risorgimento, the notion of hegemony has seen its greatest developments in studies of international relations.

- J. Nye, “Soft Power”, Foreign Policy, 1990.

- J. Nye, Soft Power, the Means to Succeed in World Politics, Public Affairs, 2004.

- P. Golub, “Soft Power, Soft Concepts and Imperial Conceits”, Monde chinois nouvelle Asie, 2020.

- “Tortoise v hare”, The Economist, 2017.

- P. Golub, op. cit.

- Numerous internal policy measures are not considered here.

- H. Angang; “Embracing China’s ‘New Normal’”, Foreign Affairs, 2015.

- X. Zhao, “ Decoupling Economic Growth from Carbon Dioxide Emissions in China: A Sectoral Factor Decomposition Analysis ”, Journal of Cleaner Production, 2017.

- J. Percebois, Chapter 49 “Énergie” in Xavier Greffe et al. (dir), Encyclopédie économique, Economica, 1990.

- J-P. Hansen et J. Percebois, Énergie. Économie et politiques, De Boeck, 2015

- Sources: The Economist, Pocket World in Figures 2011, Profile Books, 2010 and Pocket World in Figures 2021, Profile Books, 2020.

- AFP, “Émissions de CO2 : brouillard sur les prévisions chinoises”, 2021.

- A. Garric, “De timides avancées sur le climat”, Le Monde, 2020 ; A. Garric, “2021, année cruciale dans la lutte contre le dérèglement climatique”, Le Monde, 2021.

- Source: International Energy Agency, CO2 Emissions From Fuel Combustion, 2017 Edition.

- International Energy Agency, World Energy Outlook 2017, OECD/IEA, 2017.

- “A greener horizon”, The Economist, 2020.

- S. Nicholas, “A New Generation of Coal Power in Belt and Road Countries Would Be Toxic for the Environment and for China’s Reputation”, South China Morning Post, 2019.

- T. Laconde, “Transition énergétique ; des efforts qui tardent à payer”, La Jaune et la Rouge (École Polytechnique), 2019.

- C. Shearer et al., “Can China’s central Authorities Stop a Massive Surge in New Coal Plant Caused By Provincial Overpermitting?”, CoalSwarm, 2018

- C. Shearer et al., “Out of Step. China Is Driving the Continued Growth of the Global Coal Fleet”, Global Energy Monitor, 2019.

citer l'article

Jean-Paul Maréchal, China’s Climate Realpolitik, Sep 2021, 23-30.

à lire dans cette issue

voir toute la revue