Economic Growth and Climate Change — Beijing’s Hard Choices

Thibaud Voïta

Associate researcher at the IFRI Energy and Climate CentreIssue

Issue #1Auteurs

Thibaud Voïta

21x29,7cm - 153 pages Issue #1, September 2021

China’s Ecological Power: Analysis, Critiques, and Perspectives

China’s emergence as a global economic power in recent years was accompanied by a growing role on the global climate stage. But this was not necessarily obvious since the fight against climate change has not always been one of Beijing’s priorities and may even appear to contradict its national objectives.

First, in terms of growth, China’s emergence as the world’s second largest economic power (and probably the first within the next few years) was only possible through an impressive increase in its energy consumption, and more specifically through coal, which remains by far the dominant source in the country’s energy mix with a little less than 60 % 1 . At the same time that its economy was growing, its greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions reached record level and by 2004, China had become the world’s largest emitter 2 . But in the second half of the 2000s, faced with the environmental and climatic consequences of its growth and energy security pressures, Beijing had to start massively investing in clean energy, renewables, and energy efficiency, which created a huge market for its companies, both nationally and internationally. Then, in the first half of the 2010s, China actively worked to join the Paris Agreement.

Yet at the same time, since the 2000s, China showed a significant acceleration in its foreign investment, particularly by companies in the fossil fuel sector and by constructing coal-fired power plants in various countries. But China is struggling to overcome this addiction : the equivalent of nearly 247 GW of coal-fired power plants (which is enough to supply Germany with electricity) are currently under construction, compared with the closure of only 9 GW 3 4 .

This paper aims at showing how China is being forced to move forward on climate issues, despite conflicting pressures arising primarily from economic growth.

China as a major climate player

Since 2004, Beijing has been the world’s largest GHG emitter, the United States. While its emissions seemed to have plateaued in 2013-2014, hovering around 9.80 gigatonnes emitted per year, they rose again in 2017, up to 9.84 gigatonnes, and have continued to rise ever since. In comparison, that same year 2017, total global emissions amounted to 34.74 gigatonnes, with the second largest emmitter, the United States, accounting for 5.27 gigatonnes 5 . In addition, the 2020 respite related to the Covid-19 crisis and the freeze of certain activities has proved very brief. At the beginning of 2021, we learned that Chinese emissions were quick pick up again, rising by 4 % in the second half of 2020, which is an increase by 1.5 % compared to the total emissions of 2019 6 . All in all, China emits just under 30% of the planet’s total GHG emissions.

In recent history, there certainly have been some modest yet numerous signs of political will to tackle this problem in an increasingly direct manner. During the first half of the 2000s, Beijing studied the possibility of calculating its green GDP, that is to say the traditional GDP from which losses related to environmental damage would be subtracted 7 . Despite several efforts in this direction, the project remained dormant until the announcement 15 years later, in June 2021, by the city of Shenzen that it was adopting an equivalent indicator. This “Gross Ecosystem Product” includes 19 indicators related to natural ecosystems (forests, wetlands, oceans, etc.) and artificial ecosystems (farms, pastures, etc.) 8 .

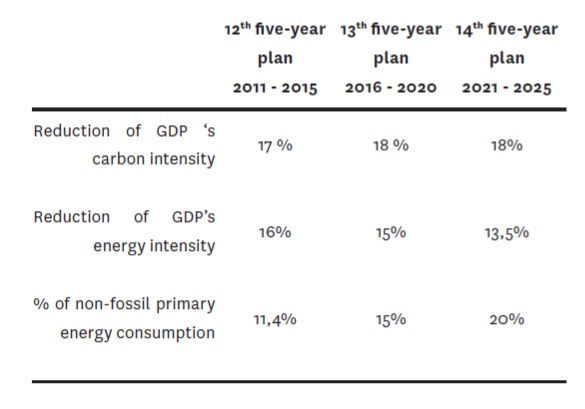

The 2000s have nevertheless seen the growing importance of climate issues, addressed in particular in terms of improving energy efficiency and as a way of responding to energy security concerns. The various Five-year plans were initially — starting with the 11th plan from 2006 to 2011 — given energy intensity targets, meaning energy consumed per unit of GDP produced. This in itself is only indirectly linked to a reduction in emissions as it does not imply a reduction in energy consumption or the use of decarbonized energy sources. Then, in 2011, the Five-Year Plan included a carbon intensity reduction target — which is also not a guarantee of absolute GHG reduction — which would be supplemented by new absolute targets in 2016 (see Table 1). The protection of the environment has even appeared in political thought with the emergence of the concept of “ecological civilisation” (which is vague in theoretical and political terms), enshrined in the 2012 Constitution of the Chinese Party which advocates cooperation on climate change and the acceleration of the energy transition 9 .

TABLE 1 • Carbon intensity reduction objectives in previous Chinese Five-year plans 10

At the international level, China waited until the 2010s to establish itself as a driving force in climate negotiations. As a result, the 2000s ended badly for Beijing,following the failure of the United Nations Climate Conference held in Copenhagen in 2009 (COP 15) where China was singled out for its lack of cooperation 11 . Things started to change as the COP 21 approached, especially thanks to the work done with the Obama administration. A first agreement between the two countries on reducing greenhouse gases before the COP 20 in 2014 allowed the emergence of a new Chinese-American leadership on the matter and sent a very strong international signal, which culminated in the signing of the Paris Agreement in December 2015 12 . Unfortunately, the election of Donald Trump and the announcement of the United States’ withdrawal from the Paris Agreement strained the partnership. During the Trump era, China played a more ambiguous role, despite participating in several initiatives that allowed the country to reaffirm its role with respect to climate change on the international stage: a ministerial summit with Canada and the EU in September 2017, participation and presence of Xie Zhenhua at the Global Climate Action Summit in San Francisco in 2018 (organised by Jerry Brown, then Governor of California, and not by the federal government), participation in the UN Climate Summit in 2019 where China was the shared leadership of an initiative on nature-based solutions (such as reforestation or prairies and wetlands extension) 13 . In addition, China is set to host a UN summit on biodiversity in Kunming in autumn 2021 (the summit was initially planned for 2020, but it has been postponed due to the Covid-19 pandemic).

If many hope that the European Union will carry the torch left by Obama and work with China on climate issues, the latter has tempered Brussels’ ambitions and has made it clear that climate cooperation comes after other priority issues. And so, China only agreed to a joint climate declaration with the EU after the recognition of its market economy status, which will push this declaration’s finalization back by one year 14 . China is also taking a more aggressive position in climate negotiations, sometimes returning to positions that were believed to have been abandoned in favour of the “spirit of Paris” that made the COP 21 successful. In particular, China once again started to use the “shared but different responsibility” principle, which stipulates that developed countries with the largest accumulated carbon footprint must increase their support to developing countries (including China) in the fight against climate change 15 .

The election of Joe Biden and the return of the United States to the climate stage has changed the deal once again. It is still too early to assess China’s potential readjustment, but it is interesting to note that very shortly after Biden’s election and John Kerry’s appointment as special envoy on climate, Chinese negotiator Xie Zhenhua came out of retirement to resume his duties 16 . Xie had worked with Kerry in preparing the Paris Agreement, and this is the second time he has returned to his former role when he was supposed to be retired. The fact remainsthat the first exchanges between the two old acquaintances and their respective administrations have not led to any definitive results 17 . In any event, it should be noted that the EU is struggling to establish a privileged relationship with Beijing, who remains more receptive to Washington’s calls.

Climate pragmatism and diverging priorities

China’s position remains equally complex at the national level, with the fight against climate change still subject to growth demands. During the Maoist era, strongly influenced by the Soviet Union, China sought to use nature and its resources to develop its manufacturing base. This trend accelerated with the country’s growth in the 1980s. And so, the country developed without really considering the impact of its growth on the environment and even less so on the climate, relying on its coal reserves and developing its heavy industry. The question now in the early 2020s is whether the country’s growth targets can really be compatible with the 2030 peak in GHG emissions or the carbon neutrality announced for 2060. However, the new Five-year plan, which spans the first half of the decade, must still be clarified and does not answer these questions at the time of writing. Experts differ on how to interpret the new Chinese objectives especially since, in 2020 18 , China still has the equivalent of 247 GW of coal-fired power plants under construction — more than the total capacity of the United States — which will make it difficult to achieve these carbon targets 19 .

Not surprisingly, Beijing’s development-centered policy creates tensions and disagreements within the government itself and sometimes forces leaders to walk a fine line. First, environmental or climate issues can threaten social order as was seen in the 2000s with the increase in protest movements concerning the pollution of rivers and lakes, or at the unprecedented degradation of air quality 20 . More recently, in 2019, major (and rare) demonstrations were held in the city of Wuhan to protest against plans for of a waste incineration plant 21 . However, the country needs to maintain rapid growth in order to keep absorbing the number of young graduates entering the labour market, and more generally to maintain social peace.

The government is therefore faced with the daunting task of continuing to promote growth while preserving the climate. This leads to, among other things, measures aiming at achieving “green growth”, which include support for so-called green technologies: renewable energy, electric vehicles, carbon sequestration, etc. Nevertheless, consensus on these topics is only superficial and can sometimes show cracks, as this was seen with former finance minister Lou Jiwei, who recently and publicly expressed concern about the impact of environmental reforms on the country’s growth. His concerns are strongly echoed by local governments, which are sometimes reluctant to implement the guidelines coming from Beijing 22 .

These contradictions are also reflected in foreign policy. China has placed the principle of non-interference at the centre of its foreign relations and, unfortunately, climate issues do not seem to be an exception this rule 23 . And so, through its New Silk Roads initiative, Beijing can sell both wind turbines and coal-fired power plants, as it does to countries such as Pakistan as well as at the EU’s doors, which is not without concern for Brussels 24 .

An impossible position in the long term?

The fact remains that the world is changing, climate change is accelerating, and China’s attitudes, inherited from recent decades, are increasingly difficult to maintain. We mentioned the negative impact of COP 15’s failure. This trend could accelerate. Last September, China responded by announcing a target to be carbon neutral by 2060, and the country is also actively seeking to reduce its dependence on coal. Beyond these announcements, the country’s evolving institutions could mark the beginning of a paradigm shift. For example, in 2019, we saw the strengthening of the Ministry of the Environment (renamed Ministry of Ecology and Environment, MEE) at the expense of the all-powerful National Development and Reform Commission (NRDC) 25 . In addition, the MEE recently published a blacklist of the most polluting projects of the New Silk Roads initiative, calling on Chinese banks to no longer support investments in these projects. Some see this as a sign of a possible ban on foreign investment in coal 26 . Finally, if there are currently no youth movements in China similar to Fridays for Future, protests could increase in the future as the effects of climate change start to be felt 27 .

China’s national and international climate positions can appear perplexing. Based on its announcements, we could think that Beijing is accelerating the fight against climate change. However, the reality seems much more ambiguous as leaders try to reconcile the seemingly divergent, or even contradictory, objectives of promoting a low-carbon society while maintaining strong economic growth, maintaining low unemployment and enriching the population, all in order to maintain social peace. If Beijing manages to reconcile these objectives, then it will have succeeded in solving the seemingly impossible equation of green growth.

Notes

- Reuters Staff, “Coal’s share of China energy mix falls to 57.7% in 2019 – stats bureau” Reuters, 2020.

- “How is China Managing its Greenhouse Gas Emissions”, China Power, 2018, updated in August 2020.

- Global Energy Monitor, Sierra Club, CREA et al. “Boom and Bust 2021. Tracking the Global Coal Plant Pipeline” Global Energy Monitor, 2021.

- “Analysis : China’s CO2 emissions surged 4% in second half of 2020”, Carbon Brief, 2021.

- China Power, op. cit ; [ndlr] see also the Infography titled “Preface: Chinese Statistics”, page 6.

- Carbon Brief, op. cit.

- “Le PIB vert, si proche et si loin”, China Analysis, Asia Centre, n°9, 2006.

- “China’s tech hub Shenzhen moves ahead with GDP alternative that measures value of ecosystem goods and services”, South China Morning Post, 2021.

- H. Wang-Kaeding, “What does Xi Jinping’s New Phrase ‘Ecological Civilization’ Mean”, The Diplomat, 2018.

- Objectives are set compared to 2005 levels.

- “How do I know China wrecked the Copenhagen deal? I was in the room”, The Guardian, 2009

- “Changement climatique : la Chine règne-t-elle désormais sur les COP ?” Asialyst, 2017.

- Reuters Staff, “China to tackle climate change with ‘nature-based solutions’ ”, Reuters, 2019.

- T. Voïta, “4 défis que devra relever la Chine pour être un partenaire fiable dans la lutte contre le changement climatique”, Huffington Post, 2018.

- Ibid et Asialyst , op. cit.

- “Climate veteran Xie Zhenhua returns as China’s special envoy”, Climate Home News, 2021.

- “Big thing : The fraught US – China climate relationship”, Axios Generate, 2021.

- “Q&A : What does China’s 14th ‘five year plan’ mean for climate change?”, Carbon Brief, 2021.

- Global Energy Monitor (GEM), Centre for Research on Energy and Clean Air (CREA) “China Dominates 2020 Coal Plant Development”, Briefing, 2021.

- See also “China blames growing social unrest on angst over pollution”, The Guardian, 2007 ; Y. Deng, G. Yang, “Pollution and Protest in China : Environmental Mobilization in Context”, The China Quarterly, 2013.

- “China has made major progress on air pollution. Wuhan protests show there’s still a long way to go”, CNN, 2019.

- M. Velinski, “China’s Ambiguous Positions on Climate and Coal”, Éditoriaux de l’IFRI, 2019.

- K.S. Gallagher, R. Bhandary et al., “Banking on coal? Drivers of demand for Chinese overseas investments in coal in Bangladesh, India, Indonesia and Vietnam”, Energy Research & Social Science, 71, 2021.

- “China pivots to old ally Pakistan for coal after Australia spat”, Nikkei Asia, 2020 ; “Why the Balkans is struggling to kick coal”, China Dialogue, 2020.

- M. Velinski, op. cit.

- “Belt and Road pollution blacklist discourages fossil fuel investments”, Financial Times, 2020 ; “China’s environment ministry floats ‘ban’ on coal investment abroad”, Climate Home News, 2020.

- Only one activist, Howey Ou, is officially part of the movement. See “Einsame Aktivistin in China gibt nicht auf”, Energie Zukunft, 2020.

citer l'article

Thibaud Voïta, Economic Growth and Climate Change — Beijing’s Hard Choices, Sep 2021, 19-22.

à lire dans cette issue

voir toute la revue