European Strategic Autonomy in 2020

Alberto Alemanno,

Jean Monnet Professor in European Union Law & Policy and founder of The Good LobbyAnu Bradford,

Henry L. Moses Professor of Law and International Organization at the Columbia Law SchoolThierry Chopin,

Special Advisor to the Jacques Delors InstituteCaroline de Gruyter,

European Affairs correspondent for NRC HandelsbladDaniel Fiott,

Security and Defence Editor at the EU Institute for Security Studies (EUISS)Ulrike Guérot,

Benjamin Haddad,

Pierre Haroche,

LecturerYannis Koutssomitis,

Ivan Krastev,

Political scientist and chairman of the Center for Liberal Strategies in SofiaHans Kribbe,

Charles Kupchan,

Senior Fellow at the Council on Foreign Relations (CFR) and professor of international affairs at Georgetown University in Washington D.CBrigid Laffan,

Emeritus Professor at the European University InstituteEuropean Strategic Autonomy in 2020,

Jean-Dominique Merchet,

Joseph Nye,

Simone Tagliapietra,

Senior Fellow at Bruegel on climate and energy policy and on the political economy of global decarbonisationNathalie Tocci,

Tara Varma,

Nicolas Véron,

Senior fellow at Bruegel and at the Peterson Institute for International EconomicsPierre Vimont,

Ambassador to the United States from 2007 to 2010Cornelia Woll,

Charles Wyplosz

29/12/2020

European Strategic Autonomy in 2020

Alberto Alemanno,

Anu Bradford,

Thierry Chopin,

Caroline de Gruyter,

Daniel Fiott,

Ulrike Guérot,

Benjamin Haddad,

Pierre Haroche,

Yannis Koutssomitis,

Ivan Krastev,

Hans Kribbe,

Charles Kupchan,

Brigid Laffan,

European Strategic Autonomy in 2020,

Jean-Dominique Merchet,

Joseph Nye,

Simone Tagliapietra,

Nathalie Tocci,

Tara Varma,

Nicolas Véron,

Pierre Vimont,

Cornelia Woll,

Charles Wyplosz

29/12/2020

Voir tous les articles

Voir tous les articles

European Strategic Autonomy in 2020

When Ursula von der Leyen spoke about a “Geopolitical Commission” when she took office in 2019, the disruption brought about by the year 2020 could not quite be predicted.

Faced with the world’s upheavals, caught up in between Sino-American rivalry, it is essential to assess and question the Union’s position in the world and its perspectives for the future. At the heart of this endeavour is a debate on the meaning of European strategic autonomy.

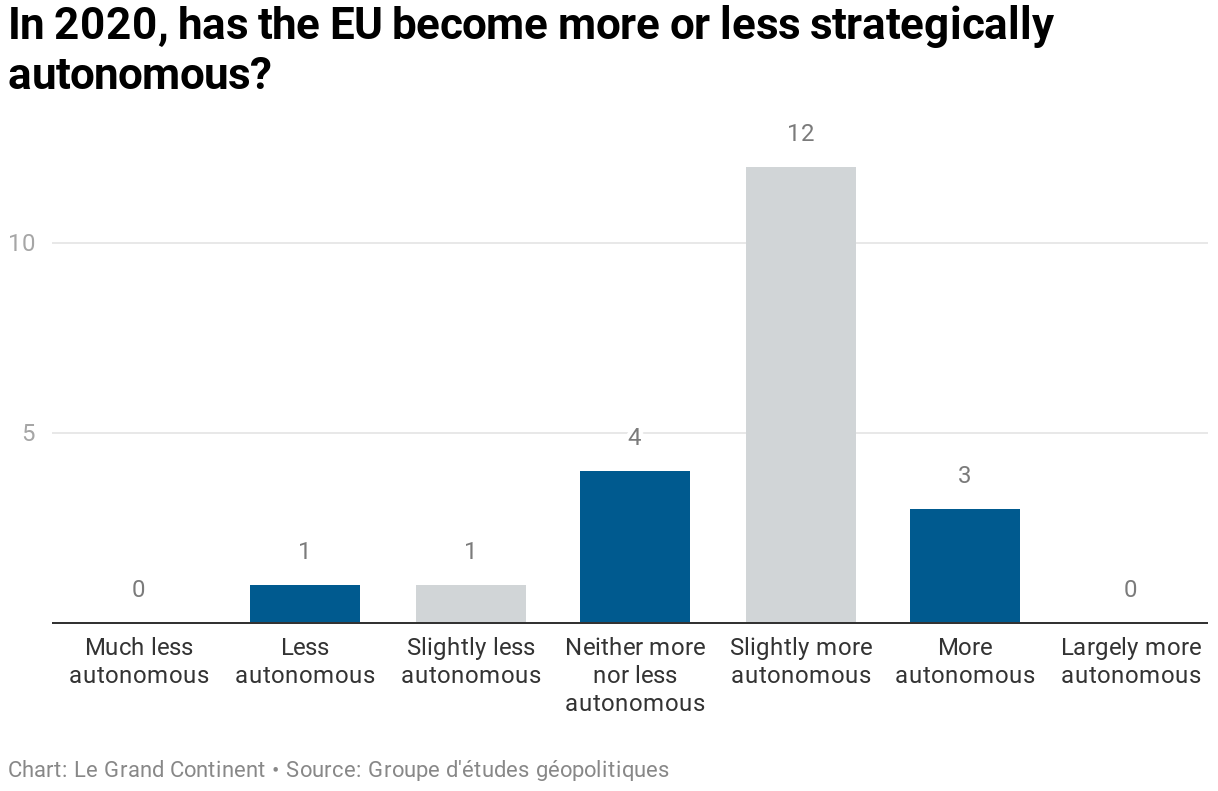

As part of the Groupe d’études géopolitiques’ publications, following a major interview with the French President and a long analysis written by the High Representative of the Union for Foreign Affairs and Security Policy, we have asked some twenty scholars, observers and experts from multiple horizons, nationalities and fields of expertise to position themselves on a scale from 0 (“the EU has become less strategically autonomous”) to 5 (“the EU has become more strategically autonomous”), explaining their mark with a short text

Alberto Alemanno

Jean Monnet Professor in European Union Law & Policy at HEC and Founder of the Good Lobby

1/5

In 2020 the EU has become less strategically autonomous due to its major regression on the rule of law. In other words, how can the EU increase self-sufficiency at the very same time it departs from its foundational self-organisational principle of the rule of law?

Historically, what brought together – and kept together – EU countries is not only a set of shared rules, but also and especially a deeper commitment to abide by them. Yet recent events, from the EU response to Covid – both as a health and financial crisis – to Brexit itself, are putting into doubt the Union’s adherence to, and relationship with, the rule of law. Here’s how and why this might have consequential effects for the Union’s strategic autonomy.

Amid Covid, the EU nonchalantly suspended most of its existential and operational rules, from Schengen free-travel area to state aids. Those rules being now in a limbo, they are difficult to reinstate, and might have been enduringly damaged. This builds upon another disturbing, present-day trend: the EU Commission’s reluctance to act as a guardian of the Treaties by going after those countries that depart from EU obligations. Against such a backdrop the EU has been turning a blind eye to major, systemic infringements of the rule of law, such as the attacks to judicial independence or that of the media in Hungary and Poland, and that despite those breaches having already been found by the ECJ. Yet the most spectacular disregard for the rule of law happened when, during the December 2020’s EU Summit, the EU member states – in a bid to persuade recalcitrant member to sign off the EU budget and Recovery Plan – committed a coup by illegitimately replacing the Parliament and Commission, in full disrespect of the principles governing the Union as a community based on the rule of law.

2020 has revealed the fragility of the rule of law underpinning the Union’s democratic life. This self-inflicted, complacent erosion of the rule of law is inevitably set to affect the EU’s ambition to self-sufficiency. The Union can’t be and appear a democracy when it no longer acts as one. Instead, to acquire its long-dreamt strategic autonomy, the Union must hold on to its core values and practices. This should be all the more so in a time of uncertainty and fear. Ultimately, the rule of law is a sine qua non condition for the Union’s strategically autonomous future.

Anu Bradford

Anu Bradford is Henry L. Moses Professor of Law and International Organization and the Director of European Legal Studies Center at Columbia University. She is an author of “The Brussels Effect: How the European Union Rules the World” (OUP 2020).

3/5

In many ways, the EU emerges from the year of 2020 stronger than before. Despite the calamity of the pandemic, the EU has shown its collective capacity to act decisively. The vaccine developed in Europe is now being procured and administered under a common EU vaccine strategy. This past July, the EU leaders agreed to a historical 750-billion-euro Recovery fund to restore European economies. These developments may pave the way towards an EU health union and closer fiscal integration, showing how the crises can usher in a stronger and more autonomous EU.

Yet whether we talk about military, economic, or technological independence, the EU remains far from being able to declare itself strategically autonomous. The EU is not a military power—it is questionable if it will ever be, or if it even wants to be one. The EU also remains vulnerable to the US’s ability to weaponize the dollar’s hegemony as long as the euro remains a small share of global foreign exchange reserves. The EU has further not made significant inroads towards compromising US and Chinese hegemony in technology.

For example, when it comes to regulating technology, the EU is able to assert its sovereign vision effectively. The year 2020 further entrenched this global regulatory power with the unveiling of significant new regulatory acts and initiatives. Yet, the EU should not only strive to be a global referee in the technology race between the US and China; it must develop its own technological capabilities to become a more autonomous player. A narrow industrial policy focused on creating European champions does not offer the right path towards technological sovereignty; European Google will not emerge through protectionism. Completing the digital single market and the capital markets union, together with attracting the world’s best innovative talent to Europe are much more likely to enhance the EU’s capabilities and, with that, technological sovereignty.

Thierry Chopin

Thierry Chopin, professor at the Université catholique of Lille (ESPOL), special advisor, the Jacques Delors Institute

2,5/5

The end of the year 2020 was marked by the deal between the EU and the United Kingdom on post-Brexit relations. It is remarkable that the 27 EU member states displayed a united front against the British. The balance of power was clearly in favour of the EU, a situation which can be explained by several factors, some of which could apply to the management of other strategic challenges for the EU : an acute awareness of a higher common interest – the absolute need to preserve the integrity of the internal market as a fundamental aspect of the EU’s political existence; the unanimous will not to grant the United Kingdom, as a third country, a more favourable status outside the EU than as a member state; the EU’s economic and commercial weight and lesser commercial dependence on the United Kingdom than the other way around; the unanimous mandate given by the 27 member states to the EU’s chief negotiator, Michel Barnier, who embodied the unity of the Union.

From a geopolitical point of view, it is interesting to note that the necessity for the EU-27 to negotiate with a state destined to become a third country was a unifying factor. Moreover, surveys conducted following Brexit suggest that European public opinions has become more favourable to participation in this Union. One of the lessons that can be drawn is that what binds member states together is also what distinguishes them from the outside, and identifying an outsider can strengthen internal cohesion. This is one of the important geopolitical lessons of Brexit for the EU, a lesson that can be useful for other external challenges.

Moreover, with regard to the discourse on European sovereignty, the year 2020 was marked by an awareness that Europe is facing geopolitical competition for health, technology, collective security, etc. However, the crisis has shown that Europe is ill-equipped and does not yet have the means to react effectively: slow reaction to the propaganda war waged by powers such as China and Russia in the first phase of the sanitary crisis; limited influence on the Belarusian question and lack of action in the Nagorno Karabakh conflict; laborious decision to sanction Turkey’s aggressive policy in the Eastern Mediterranean; cuts in the European defense budget; a step backwards for the German government in defence after the election of Joe Biden. Moreover, although we should rejoice over European rules introduced by the Commission to regulate GAFAM activities (competition, taxation, personal data, content), what about the means available beyond regulatory instruments? What about industrial policies that remain national? If Europeans want to counter US digital giants, we must be able to offer alternatives (an endeavour which China is successfully accomplishing), which implies considerable investments that can only be made at the European level. The importance of “size” as a crucial factor must be stressed here, not only the size of the European market but also the size of its budgetary capacity; however, progress remains to be made on this last point in Europe against China and the United States because of the fragmentation of capital markets. In other words, to be strong in global competition, one must be strong in industries, an endeavour which requires collective European investments, a collective capacity that must be replicated in many areas which are fundamental for sovereignty.

The awareness of the need to develop greater strategic autonomy at the EU level has not yet been translated into reality (apart from the defence fund and the protection of strategic assets, even if Europe must not lower its vigilance vis-à-vis China). The lessons of the situation in which Europeans currently find themselves must be drawn and lead to decisions on the means to be pooled at the European level in order to fight on equal terms in the global geopolitical and geo-economic competition. This is the condition for developing a true European “strategic autonomy”.

Caroline De Gruyter

Europe correspondent and columnist for the Dutch newspaper NRC Handelsblad

3/5

Each year, gradually, the European Union becomes a little more “strategically autonomous”. This was also the case in 2020, but not in those areas where some people continually insist that it must become so, such as Josep Borrell. By his repeating that the Union must become strategically autonomous, he is merely pointing out that it is not. When Charles Michel proclaims that “Europe is strong”, he only highlights that it is not. If it were, it would be self-evident.

Real progress is elsewhere, and goes almost unnoticed. Here are two examples:

The first is the gradual establishment of the Union’s external borders. To protect itself from Covid, Europe closed its external borders for the first time. The pandemic gave both a practical as well as symbolic meaning to such borders, crystallising the difference between “us” and “them”. The sense of belonging cannot be decreed.

Another example is Michel Barnier. Throughout his negotiations with the United Kingdom, he never described the strength of the European Union with words but projected it as self-evident through his actions and behaviour, with calm yet powerful force, having understood that boasting would have reflected weaknesses and led to disaster.

I give the European Union a three out of five. It’s a somewhat generous grade but it comes with a condition: that in 2021 European leaders stop talking about strategic autonomy as a vague objective but express it concretely in acts and behaviour.

Daniel Fiott

Security and Defence Editor EU Institute for Security Studies

3/5

Opponents may unfairly say that the EU, in its quest for greater strategic autonomy, has only progressed in rhetorical terms during 2020. The high-level public debate on strategic autonomy enabled by Le Grand Continent is a tonic for the intellectual debate, but this should not mask the real advances taken by the Union in 2020.

In defence, Permanent Structured Cooperation projects continued to be developed and €205 million was invested in preparatory defence research and capability programmes for the Union. The EU also deployed Operation Irini to the Mediterranean and an advisory mission to the Central African Republic. Illegal drilling in the Eastern Mediterranean also saw the EU impose sanctions on individuals from Turkey. Political leaders from Belarus and Russia were subject to sanctions too.

Furthermore, the EU also imposed its first cyber sanctions for attacks on the Organisation for the Prohibition of Chemical Weapons. The European Parliament established a new special committee on foreign interference in all democratic processes in the EU too, which is designed to monitor and counter disinformation and foreign interference.

More broadly, EU data, digital, AI, industrial, raw material and cyber strategies published in 2020 will now guide the billions of euros of investment that will come online as from 2021. Such measures occurred alongside the full operationalisation of the EU’s screening framework for foreign direct investment.

Finally, the EU achieved agreement on a revision of the European Stability Mechanism, which will offer the Union a lender of last resort and financial stability. Finally, the post-pandemic recovery package of €1.8 trillion represents an unprecedented attempt to recover and reform the European economy.

Ulrike Guérot

Founder European Democracy Lab

N/A

History is not a scale, history is a series of action.

Judging, on a scale of 0 to 5, whether Europe is more strategically autonomous, at the end of the perilous year 2020 and its multiple challenges, is a double-edged task. It could give the misleading – even fatal – illusion that we could assess European autonomy objectively.

Let’s say that we evaluate this European autonomy at 1,8 or 3,9 on a scale of 5. What would that mean?

The “Gramscian” reality is that while the facts may be a source of distress, European activism might be one of solace. Much has been accomplished in 2020, including some innovations never seen before. A European Recovery Plan, the first joint credits, up to 750 billion euros, has been agreed upon. A social pillar, including European unemployment insurance, is being negotiated. The strategic choice has been made to use the pandemic for the modernization of European industries and their digitalization. The objective of achieving carbon neutrality by 2050 has been affirmed anew with greater determination. A European high-speed train network is being planned. The European budget has been voted, despite difficulties linked to its being conditioned to the rule of law.

Achieving all this during zoom-meetings cannot be looked down upon. In this situation, European citizens have woken up like Sleeping Beauty. An alliance of more than 60 European NGOs (Citizens Take Over Europe, #CTOE) was formed as the European Citizen Assembly and has been meeting since May 9, 2020, every Wednesday on the Internet between 10 and 12 a.m. with a view to drafting a European constitution. This is a sign that European citizens aspire to a European autonomy and to its constitutionalization. But is it enough?

Europe lacks a firm positioning between China – winner of the crisis – and the United States. It lacks taxation mechanisms for digital technology giants, such as Amazon. It lacks a European response to Octopus – the Chinese “Zoom”. It lacks a much more welcoming policy towards refugees – one thinks of the horrible images coming from Moria. However, above all, it lacks the famous political will to make Europe strategically autonomous.

Therefore, we cannot objectively evaluate Europe’s strategic autonomy. One wonders whether the promises made on Europe’s balconies in March 2020, “Together in, together out”, will be kept. In order to keep this promise of a strategically autonomous Europe, there is still a lot to be done!

Benjamin Haddad

Director Future Europe Initiative, Atlantic Council

3/5

The European Union emerges strengthened in its unity and political identity in 2020. The Covid crisis could have profoundly accelerated divisions and nationalist reflexes, as suggested by a few initial weeks of hesitation. On the contrary, via an ambitious recovery plan this summer, but also the conclusion of the Brexit chapter in recent weeks, the European Union ends the year with reaffirmed unity. Chinese mask diplomacy propaganda attempts against European public opinion have failed.

But the year 2021 will be decisive. The Biden administration represents a clear opportunity for cooperation on major global issues, from the post-Covid era to the fight against climate change. But the temptation will be great for some to abandon the efforts undertaken in recent years in the fields of defense or trade, only to rely again on a more predictable American ally. In order to exist as an independent actor within the transatlantic relationship, Europe has every interest in continuing to invest in its own sovereignty. However, the first signals, particularly coming from Berlin, are not encouraging in this respect.

Pierre Haroche

European Security Researcher at Institut de Recherche Stratégique de l’École Militaire (IRSEM)

3/5

For the European Union, the strategic year 2020 has been a moment of truth. Since 2017, the EU has sought to strengthen its strategic autonomy with the establishment of the European Defence Fund and permanent structured cooperation. This incremental institutional construction gave way this year to a direct confrontation with the new power competition.

Although the Covid crisis has crystallized the Sino-American rivalry, previously divided Europeans have also consolidated their position with regard to Beijing, whether by de facto sidelining Huawei from their 5G networks or by collectively asserting their desire to reduce external dependence in strategic areas, which mainly concern Chinese influence. Considerations over the Chinese threat has pushed the EU towards a broader definition of the concept of strategic autonomy, including with regards to economic matters.

At the regional level, Europeans have confronted the Turkish power. Ankara’s all-out activism has spread from Syria to Libya, from confrontation with Greece and Cyprus to support for Azerbaijan. If the EU’s response to provocations in the Mediterranean is still timid, Europeans have gradually closed ranks.

The election of Joe Biden could be conducive to a revival of the transatlantic partnership on two aspects: technological and industrial cooperation against China; assertion of strategic autonomy to engage with regional crises, so as not to overburden the US.

Yannis Koutsomitis

European affairs analyst

3/5

2020 will probably go down in history as the world’s most dreadful year since World War II. The Covid pandemic has brought the world’s economies to their knees and put has the societies in dire stress, especially in Europe. However, it has been a year during which the EU has realized, albeit the hard way, that it needs to reposition itself as an autonomous power in the global arena. European leaders made a remarkable breakthrough in August, as they found common ground to support member-states’ economies and societies by letting the Union issue common debt, while preserving the rule of law. This historic decision has strengthened the EU’s unity and resilience. The EU’s decision to increase the bloc’s emission-reduction target to 55% by 2030 will make Europe less dependent on fossil fuels from the Middle East and Russia and paves the way for an energy autonomous future by 2050. The EU’s Digital Strategy is a positive step in positioning Europe as a competitive player in the global technology field.

The EU didn’t get a better score because it still can’t agree on how to strike a common strategy on foreign affairs and defence policy. Regional geopolitical crises in Libya, Syria and Caucasus are vivid examples of Europe’s inability to find a unified approach and protect its strategic interests in her own neighborhood. Overall, the European Union is gradually walking a new path towards its strategic autonomy, but it needs to move fast on cutting-edge technology and reach basic consensus in foreign affairs.

Ivan Krastev

Ivan Krastev is the chairman of the Centre for Liberal Strategies in Sofia and permanent fellow at the Institute for Human Sciences, Vienna

2/5

When one of the most powerful rulers taking part in the Vienna Congress, Tsar Alexander I., fainted during one of his visits to Vienna in 1814, the initial suspicion was that he had been poisoned. Later, it became clear that the Russian sovereign was suffering from extreme exhaustion as a result of excessive ball dancing.

Two centuries later, in 2020, the foreign policy of the European Union almost fainted because of excessive zooming. When the Union’s foreign policy was turned into a home office mode, it produced a lot of concepts but failed to initiate many actions. While Russia and Turkey used the geopolitical vacuum opened by the pandemic to assert their interests in the European neighborhood, Brussels was basically passive and pre-occupied with reconciling the diverging interests of the different member states. While zooming, Brussels failed to define an effective strategy for addressing the crisis in Belarus. It went simply absent from the conflict in Nagorno-Karabach. It failed to demonstrate unity concerning Lybia, while the blockage of the start of negotiations with North Macedonia and Albania weakened its position in the Western Balkans. While the newly found concept of strategic autonomy of the EU was meant to promise a more active presence of the EU in the world, in 2020 EU’s strategic autonomy meant mostly absence from the world scene. The Covid crisis made others view the EU as a risk-averse global player that means well, thinks well and does not do much. I hope this is going to change when the pandemic is over.

Hans Kribbe

Author: The Strongmen: European Encounters with Sovereign Power (Agenda Publishing, 2020)

4/5

Strategic autonomy is not a state of affairs, it is the process of Europe coming of age, of gradually building up “immunity”, of the EU learning to stand on its own feet in the world. Inevitably, this process is shaped by crisis, defeat and humiliation. It is when we are forced to confront our inadequacy and mortality that resilience grows. That which does not kill us makes us stronger, as Nietzsche taught.

This has been a grim and testing year for everyone. But by and large Europe’s body politic has survived the pandemic in one piece. It has shown signs of wanting to “toughen up”. Do we want to depend on China for essential (medical) equipment, become aid recipient rather than aid donor? Clearly, we don’t. We learned about the need for effective European procurement structures in the global race for vaccines. We saw flaws in Europe’s arsenal to combat the economic downturn, and agreed a new and massive EU Recovery fund.

In its role as the great revealer, Covid ruthlessly uncovered the EU’s political fragility, as it did in other countries. This will take time to address. But the virus also showed that for some things we best rely on ourselves, something that Donald Trump had already made clear before. Not that long ago, if you uttered the words “strategic and “autonomy” in Brussels, you’d be laughed out of the room. Only fools are laughing now.

Charles A. Kupchan

Charles Kupchan is a senior fellow at the Council on Foreign Relations (CFR) and professor of international affairs at Georgetown University in the Walsh School of Foreign Service and Department of Government.

3/5

The EU has made modest progress toward “strategic autonomy.” The issue is now receiving the political attention it deserves. Active discussions are under way about how the EU can best increase its geopolitical heft and acquire more collective military capability. However, it remains to be seen whether the current deliberation leads to consequential outcomes and a quite significant increase in Europe’s ability to project military power. The jury is still out. Moreover, I do not like the term “strategic autonomy.” I prefer talk of a strong European pillar. Europeans will more often than not act alongside their American partner. Europeans should also be prepared to act alone if necessary. But let’s stop all the theological debate about “autonomy” and focus much more on building capability. Less talk and more action please.

Brigid Laffan

Director and Professor at the Robert Schuman Centre for Advanced Studies and Director of the Global Governance Programme at the European University Institute (EUI), Florence

3/5

In 2020 the discourse on strategic autonomy became much more pronounced in Europe, driven by great power competition and the impact of the Covid pandemic. 2020 was the year when the Union began to grapple with what strategic autonomy might mean and how it could be achieved across multiple domains. The concept made its way into the conclusions of the October European Council. Put simply, the EU has embarked on an ambitious effort to translate a vague and ambiguous concept into a concrete project. Part of this effort was to launch a major review of European trade policy in July. A key driver of the review is to make Europe more assertive with regard to trade defense mechanisms, monitoring of subsidies and the design of a carbon border levy. The latter is central to a related strategic policy, the European Green deal. The pandemic exposed vulnerability to a small number of suppliers in key areas such as the supply of PPE and related medical products. Europe will not turn its back on global supply chains but will seek to limit its exposure. The challenge for Europe in trade is to enhance its strategic use of its market power while remaining open because strategic autonomy could unleash protectionism. Technology and the big tech giants form another dimension of strategic autonomy. Here Europe is much weaker as it has failed to create powerful digital companies. And then there is defense and security where Europe has failed in the past to translate defense expenditure into real capability.

Bruno Macães

Former Minister for European Affairs of Portugal. Author.

3/5

I think there have been some baby steps. Contrary to what you sometimes hear, the focus is not on security but on geoeconomics and in this area the EU has continued to develop tools that allow it to approach markets and trade more strategically than before. The bloc should be able to reciprocate when its interests are affected. This applies to tariffs, public procurement, and control over supply chains. We saw how Trump was unusually cautious when considering whether to move against EU interests, or how China is now starting to take the EU more seriously. The recovery plan is also good news because it creates a new asset class and will no doubt help expand the international role of the euro. In the security area, the balance is less positive. I think less about the Eastern Mediterranean – where the EU continues to have leverage – than Belarus. It was disappointing to confirm that the EU continues to have difficulty using its influence in the immediate neighbourhood. Karabakh was another example. I am less pessimistic than others because I continue to think that the main arena where the EU can play a superpower role is geoeconomics. Most of the problems we face could be addressed if the EU’s economic clout would be better used to pursue strategic aims. If we need institutional changes those would also be in this area. 2021 will be a pivotal year. Eyes are on the EU-China investment treaty and on the geopolitics of technology.

Jean-Dominique Merchet

Defense columnist l’Opinion

2,5/5

It is too early to know whether 2020 will have seen any progress in Europe’s strategic autonomy, as professed by the sycophants of powers holders, whether in Paris or Brussels. The year that is drawing to a close has indeed seen some extremely important developments, which could bring about a paradigm shift. The months and years ahead will tell us if this is the case.

The pandemic. Two major accomplishments: the decision of member states to take on joint debt and the massive common purchase of vaccines by the European Commission. We do not know whether the European Recovery Plan is a first step towards the establishment of a sustainable borrowing mechanism. If it is, it will be a qualitative leap forward. The distribution of vaccines is equally important. By pooling the purchase at EU level, the Union is acting on the right scale on a subject that concerns each individual. If the vaccination campaign is successful, this decision will be a milestone.

Digital policy. The adoption of the Digital Services Act (DSA) and the Digital Market Act (DMA) is an important moment for Europe, but it is still impossible to assess the real effects of such measures on the digital giants. One basic fact remains: Europe does not have digital champions …

Brexit. Although the 27 remained undivided and the UK withdrawal is made within the framework of an agreement, the departure of a Member State cannot be considered as good news for the EU, whose principle is to bring all Europeans together. Except, like some Frenchmen do, ones adheres to the Stalinist maxim: a party becomes stronger by purging itself?

Biden. For many Europeans, the election of a courteous Atlanticist in the White House recreates a comfortable ecosystem that is not very favorable to European strategic autonomy. Trump’s re-election would have, on the contrary, undoubtedly strengthened such ambitions.

Joseph Nye

University Distinguished Service Professor, Emeritus and former Dean of the Harvard’s Kennedy School of Government

3/5

The Trump years increased distrust and unpredictability in transatlantic relations, and this increased Europe’s attention to strategic autonomy. But the underlying structural situation did not change. Europe still shares a border with a large amoral Russia which it cannot deter alone without an American alliance. Within that structural reality, greater European defense spending and coordination is good. It is not a threat to NATO, but should be welcomed when coordinated. Europe’s efforts in the Sahel and Eastern Mediterranean are important and should increase. And Europe has begun to discover that Asia is about geopolitics and not just a matter of export markets. The Biden Administration should welcome these steps.

Simone Tagliapietra

Research fellow at Bruegel, Brussels

2,5/5

In 2020, ‘strategic autonomy’ has become one of the most utilised catchphrases in Brussels policy circles. EU officials have increasingly stressed the need of introducing strategies and measures to boost the EU’s ‘strategic autonomy’ or ‘strategic sovereignty’ in a number of areas, spanning from defense to digital, from pharmaceutical to green. However, policy vision has yet to turn into sensible policy action. Take the crucial issue of industrial policy. In March 2020, the European Commission published a plan for a ‘New industrial strategy for Europe’, a strategy primarily aimed at ‘managing the green and digital transitions and avoiding external dependencies in a new geopolitical context’, to use the words of EU Internal Market Commissioner Thierry Breton. The main underpinnings of the strategy were the need to face emerging global competitors and promote Europe’s ‘strategic autonomy’, and the necessity to face the twin ecological and digital transitions. The strategy encompassed a number of areas, from intellectual property to public procurement, and had a strong focus on competition policy – in line with the 2019 Franco-German manifesto for a European industrial policy. Covid and its massive economic implications rapidly made clear that the strategy failed to provide the strong EU industrial policy framework that is required to turn ‘strategic autonomy’ ambitions into reality. That’s the reason why, in her September 2020 State of the Union speech, President von der Leyen herself pledged to revise the industrial strategy in 2021. The economic disruption caused by Covid has forced the EU to rethink itself in a pragmatic manner, also with regard to ‘strategic autonomy’. The European Recovery Plan is just the most evident sign of this. After the year of disruption and rethinking, 2021 must be the year of action.

Nathalie Tocci

Director of the Istituto Affari Internazionali (IAI); Special Advisor to EU High Representative and Vice President of the Commission Josep Borrell, Rome

2,5/5

In the previous political-institutional cycle, foreign policy issues received much more attention than they do now. This was partly due to exogenous factors, such as the crisis in Ukraine, Brexit, the election of Trump. But all this outward attention was also resulting from an internal factor: the total inability of the Union to make progress on issues such as the reform of the Eurozone and the issue of migration.

In 2020, things have completely changed. Against the pandemic, we have found internal cohesion and solidarity on multiple issues, with the agreement on the European Recovery Plan. This has given a new impetus to the fundamental condition for a successful European foreign policy: solidarity. I find it absolutely unrealistic to think that there is a common perception of threats in Europe. The geography, history and political culture of member states prevent this. What we need to work on at the political level, and where we can really succeed, is solidarity.

While these internal measures bode well, the attention paid to foreign policy issues has dropped over the past 18 months. This can be seen very clearly in the discussions on the European budget. Although the budget has been considerably increased, the share allocated to foreign policy, the European Defence Fund and the European Peace Facility has been cut in half compared to initial expectations. As a result, the EU is much more introverted than it was a few years ago. In the midst of the pandemic, it is natural that attention is shifting towards socio-economic and health issues. That said, as we know, the multiple crises surrounding us will remain unresolved.

Ultimately, the central issue is precisely the need for a common political will to take risks and responsibilities to tackle those pressing issues.

Tara Varma

Policy fellow and head of the Paris office of the European Council on Foreign Relations

3/5

At the beginning of the year 2020, the new European Commission was barely a month old. It boasted the ambition to be more “geopolitical” and to assert itself as a power. The Covid crisis soon shuffled the cards. After a few chaotic days, it seemed clear that leadership was expected from the EU to coordinate health management efforts against the pandemic which affected member states unevenly. The Union’s dependence for the procurement of active pharmaceutical ingredients needed for the production of medicines was greeted with stupefaction. This shock was followed by an existential debate on the meaning of solidarity that led to fears of a return to the worst hours of the financial crisis, which had battered European cohesion and whose effects were still being felt in the current health crisis. Germany’s shift from the Frugal camp to that of those in favor of greater financial and health solidarity, which led to a partial mutualization of European debts, sealed the fate of European strategic autonomy in health matters. Although this area is still not part of the Union’s competences, common strategic stocks have been created thanks to pre-existing institutions and political will, as well as a common strategy for the acquisition and deployment of Covid vaccines. However, there is still a lack of European coordination on the movement of people and the implementation of common health protocols at airports, train stations and other critical locations. The Union continues to strive for strategic autonomy.

Nicolas Véron

Nicolas Véron, senior fellow at Bruegel (Brussels) and the Peterson Institute for International Economics (Washington DC)

4/5

From an economic and financial policy perspective, the agreement on the recovery plan has been the most momentous European development of 2020. Much coverage has gone to the arduous negotiations and to the challenges of apportioning the money and spending it wisely, not least as it entails grants to member states. But arguably the most lasting and structural consequence is about something else: namely, that the plan will be financed by direct issuance of securities by the European Union, or EU bonds. Whereas the EU has been issuing bonds before, the Recovery plan volumes are unprecedented. That changes everything. In the next few years, EU bond issuance will be of the same order of magnitude as that of a large EU member state. EU bonds will become a reference point for the European sovereign debt market. Their interest will be lower than that of most member states, and it will be clear to everyone that they are the best way to finance EU policies – in practice and not just in theory. After a few years, their termination will be rationally viewed as implausible. EU bonds will be used to fund other spending programs, and possibly to refinance the reimbursement of those issued for the Recovery Plan. Even though the question of which “own” (i.e. fiscal) resources back them does not need to be answered immediately, an answer will be found over time. As German finance minister Olaf Scholz and others have put it, the Recovery plan may not be a fiscal union yet, but it is a decisive step towards it.

Pierre Vimont

Senior fellow at Carnegie Europe

3/5

The European Union already acts as a strategically autonomous entity, but it does so unassumingly. At times, it even seems to be particularly careful not to show excessive audacity. Yet, throughout the Trump years, it has demonstrated a real capacity for resistance in defending the Paris climate agreement, for example, or to keep the nuclear deal with Iran alive.

In 2020, real progress has been made which augurs well for the future. The embryo of European defense has been consolidated and equally promising objectives have been set for the climate, the regulation of digital platforms or reciprocity in the commercial field. Better still, the European Recovery plan with its common borrowing mechanism is a significant upgrade which will reinvigorate the euro on financial markets.

But these promises will fizzle out if there is no real intellectual paradigm shift. The Union now needs the common political will to position itself as an autonomous power. However, many member states are reluctant to take the risk of alienating the United States or China with excessive demonstrations of independence. Even more difficult still, those member states are reluctant to make the Union what they did not foresee it could become, i.e. a player acting on the world stage for its own interests and with its own methods.

So there is still work to be done.

Cornelia Woll

Professor of Political Science, Co-Director of the Max Planck Sciences Po Center

4/5

The year 2020 dramatically ended faith in the stability of an economically integrated world order. Transatlantic and Sino-European tensions confirmed the new Commission’s geopolitical ambition. With the United Kingdom exiting, EU members had to lock shoulders and were able to agree on a common Covid Recovery Plan. At least the objective of strategic autonomy is now well identified.

Does this mean the EU has the capacity to take strategic external actions alone where and when it is necessary? Obstacles remain numerous, not least in agreeing on what is “necessary”. Strategic interests and risks are unequally distributed among member states, slowing considerably all progress on joint actions. When tensions erupted between Turkey and Greece, France would have preferred a more forceful EU sanctions approach than Germany was willing to support. Despite calls for action, the EU was invisible in the conflict in Nagorno-Karabakh. But Europe continues to speak out in unison against Russia, most recently with sanctions over the Navalny poisoning. member states also pursue a common approach to Iran, hoping to return to the Iranian deal with the new Biden administration.

To be sure, it is easy to speculate about the EU’s strategic autonomy in the shadow of NATO. Military capacity of the EU-27 is still nowhere close to replacing the transatlantic alliance. And yet, NATO’s role as a forum for a coordinated security strategy for Europe is dwindling, leading Europe to slowly broaden its own capacities, with a multitude of initiatives. The challenges of 2020 certainly confirmed this necessity.

Charles Wyplosz

The Graduate Institute, Geneva. Editor, Covid Economics

3/5

Not much has really changed. Admittedly, there was the Recovery Plan, which represents a real breakthrough, but which is poorly constructed and could, in the end, become a symbol of Europe’s inability to do things properly. Beyond the Recovery Plan, what else? Fine-tuned but ineffective statements against the destructive work of soon-to-retire President Trump. I can’t see a single strategic area where Europe has taken an initiative that could initiate a paradigm shift. With regards to the pandemic, there has been no coordination, beyond the collective purchase of vaccines from non-European laboratories (the German creator of the vaccine went to Pfizer in the United States), not even to help poor countries. Northern countries remain wary of Southern countries that tend to be reluctant to face the cost of their own economic mistakes, Eastern countries are struggling to convert to democracy and, in the middle, France is pursuing its dream of a European power that nobody else wants. Have the Germans converted to French-style industrial policy to promote European champions? I strongly doubt it. For them, European champions have to be German, with only a few remaining crumbs for the others, this philosophy will not get us very far. Lack of ambition in Germany, French romantic unrealism, we’re not moving forward, and we’ve lost Great Britain along the way.

citer l'article

Alberto Alemanno, Anu Bradford, Thierry Chopin, Caroline de Gruyter, Daniel Fiott, Ulrike Guérot, Benjamin Haddad, Pierre Haroche, Yannis Koutssomitis, Ivan Krastev, Hans Kribbe, Charles Kupchan, Brigid Laffan, European Strategic Autonomy in 2020, Jean-Dominique Merchet, Joseph Nye, Simone Tagliapietra, Nathalie Tocci, Tara Varma, Nicolas Véron, Pierre Vimont, Cornelia Woll, Charles Wyplosz, European Strategic Autonomy in 2020, Dec 2020,