European Strategic Autonomy and the Biden Presidency

Rosa Balfour,

Emil Brix,

Maria Demertzis,

Deputy Director at BruegelMichel Duclos,

Maya Kandel,

Historian and researcher at the Université Sorbonne Nouvelle Paris 3Jacob Kirkegaard,

Resident senior fellow with the German Marshall Fund of the United StatesHans Kribbe,

Charles Kupchan,

Senior Fellow at the Council on Foreign Relations (CFR) and professor of international affairs at Georgetown University in Washington D.CElena Lazarou,

European Strategic Autonomy and the Biden Presidency,

Giovanna de Maio,

Claudia Major,

Laurence Nardon,

Kristi Raik,

Director of the Estonian Foreign Policy Institute at ICDSAndrei Tarnea,

Bruno Tertrais,

Nathalie Tocci,

Pierre Vimont

Ambassador to the United States from 2007 to 2010

08/02/2021

European Strategic Autonomy and the Biden Presidency

Rosa Balfour,

Emil Brix,

Maria Demertzis,

Michel Duclos,

Maya Kandel,

Jacob Kirkegaard,

Hans Kribbe,

Charles Kupchan,

Elena Lazarou,

European Strategic Autonomy and the Biden Presidency,

Giovanna de Maio,

Claudia Major,

Laurence Nardon,

Kristi Raik,

Andrei Tarnea,

Bruno Tertrais,

Nathalie Tocci,

Pierre Vimont

08/02/2021

Voir tous les articles

Voir tous les articles

European Strategic Autonomy and the Biden Presidency

The four years that separate the inauguration of Donald Trump from that of Joe Biden have helped to accelerate the debate about the European Union’s dependence on the United States and the profound meaning of strategic autonomy.

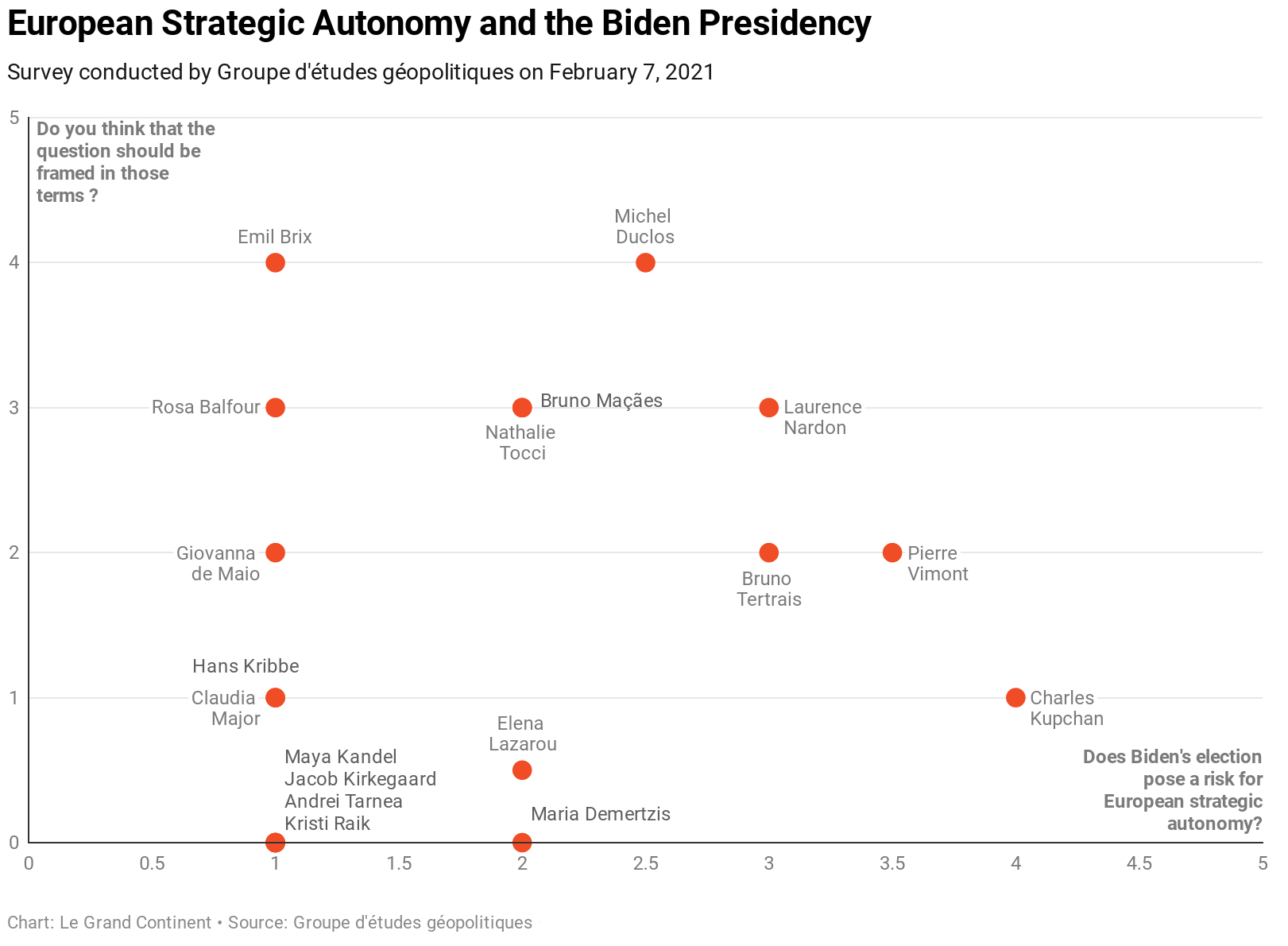

As part of the Groupe d’études géopolitiques publications on European Strategic Autonomy 1 , we asked some twenty international personalities from different horizons and backgrounds to reflect on the impact of the Biden presidency for the future of European strategic autonomy. In order to address this question from a multidimensional perspective, we asked contributors to position themselves on a scale from 0 to 5 by answering two questions:

Question 1 (Q1) Does Biden’s election pose a risk for European strategic autonomy?

0 (No, absolutely no risk) to 5 (Yes, a serious risk)

Question 2 (Q2) Do you think that the question should be framed in those terms ?

0 (No, it is not the right way to look at it) to 5 (Yes, it is a crucial question)

Contributors’ marks are represented in a graph. In order to allow them to elaborate on their choices, we also asked each author to review the fundamental issues that will shape the transatlantic relationship in the short / medium term.

This report is available in French on Le Grand Continent.

Rosa Balfour

Director, Carnegie Europe

(Q1) 1/5 | (Q2) 3/5

The biggest risk to strategic autonomy does not come from the US but from divided Europeans lacking a shared vision. Born in the NATO context, strategic autonomy has become an ambivalent concept. Many EU and NATO member states see it tied to the US: the more of one implies the less of the other. Yet, the US itself has long been asking for Europeans to up their game in security and defence with little success, so the equation does not stand up to scrutiny. Indeed, among those who invest in defence are countries pushing for strategic autonomy (eg.France) and those opposed to it (eg.Poland).

Strategic autonomy has recently acquired a broader – but imprecise – framing, charactérised by concepts such as ‘European sovereignty’, ‘economic sovereignty’, ‘geopolitical Commission’. In economics, trade, competition, Brussels strives to make a more political use of the single market and its economic tools to simultaneously strengthen its global position in the face of geopolitical rivalry and internal unity in the face of Brexit, under the cloak of strategic autonomy.This path could perhaps beef up Europe’s global clout by taking advantage of its strengths. But it does run the risk of falling into a ‘Europe first’ trap. The Biden Administration has pledged to work with allies to repair and reform the multilateral system for a rules-based order. The challenge for Europe’s strategic autonomy will be to find a balance between potentially competing goals.

Emil Brix

Austrian diplomat and historian

(Q1) 1/5 | (Q2) 4/5

Most analysts tend to complain that the European Union has become a champion of making plans for “strategic autonomy” and for a “sovereign Europe” without acting accordingly. However, an EU without a constitutional moment will not overcome this structural weakness. The threat of being left behind in the meagre role of a likeable rule-setter and sometimes referee is not yet felt strongly enough in all the capitals of the EU-27 to make them agree to radical power shifts towards Brussels. It is very unlikely that the change in the US administration will transform the piecemeal engineering tradition of the EU. In the geopolitical competition between the US and China, the risk for European strategic autonomy does not lie in the expected advantages or disadvantages of a renewed transatlantic partnership but in the medium and long-term “crowding-out effects” of global competition for economic leadership between the US and China. We might learn from the ongoing geopolitical decline of Russia that strategic autonomy comes at a price and that this price increases over time.

Nevertheless, the Biden administration represents a clear opportunity for cooperation on major global issues, including reform of multilateral institutions, the common fight against climate change and common activities where we clearly have a shared interest like the Western Balkans. But this does not mean that Europe can expect a return to the idea of the US as the global policemen. The risk that the EU puts less efforts in a more sovereign Europe in the fields of defence or possibly even trade, only to rely on a more predictable American ally, is real. Therefore, framing Biden’s election as a risk is the right way to look at the prospects of the transatlantic relations. Europe cannot relax. The underlying structural situation did not change. As Joseph Nye recently stated: “Europe still shares a border with a large amoral Russia which it cannot deter alone without an American alliance. And Europe has begun to discover that Asia is about geopolitics and not just a matter of export markets.”

Maria Demertzis

Deputy Director at Bruegel

(Q1) 2/5 | (Q2) 0/5

Joe Biden’s election brings the promise of major change with global relevance. From climate to multilateralism, trade and managing global public goods, there is a lot that the EU can agree on with the US.

We can hope that the ‘America first’ rhetoric will stop even though we understand that the US will still pursue American interests first. In the past 4 years however, the EU took big steps to promote its strategic autonomy, which de facto is an attempt to separate from the US. Is this pursuit of autonomy now justified?

While there is a lot to agree with there is also scope for significant disagreements.

The most obvious is how to deal with big tech giants. EU initiatives to regulate and tax them will create the impression that the EU is looking to attack US firms, a fact that will not sit well with the new administration.

The Biden administration will seek to continue and strengthen the US stance against China, by calling like-minded countries to form a front against it. The EU is very reluctant to do this, preferring instead to maintain a very transactional relationship with China.

Despite differences, it is hard to imagine how either the EU or the US can do better on the big issues if they pursue their interests separately. Rather than pursuing strategic autonomy, it is time to concentrate on building strategic alliances.

Michel Duclos

Senior Fellow, Institut Montaigne, Former Ambassador

(Q1) 2,5/5 | (Q2) 4/5

Should there be any risk, it remains limited. The United States will continue to prioritize other issues than Europe when it comes to crisis management and the allocation of its resources. Although the Biden administration will considerably improve transatlantic relations, it is ultimately likely to be aligned with Obama and Trump. This means that Europeans must organise themselves to deal with threats coming from the other side of the Mediterranean and perhaps from the Balkans.

This is a major issue because it would be better for both sides to develop their relationship in good intelligence. This is especially true for France because “French ideas” regarding European defence will only find a critical mass in Europe if positive impulses come from Washington as well. By contrast, if the United States are willing to reinstate their unequivocal leadership, jolts and tensions are to be expected. The French Presidency of the Council of the European Union should be an opportunity to consolidate a new transatlantic consensus on security but also on core elements of European sovereignty – technology, climate, investment, trade, China – for which an American understanding would be of common interest.

Maya Kandel

Historian, specialist in American foreign policy, associate researcher at the Sorbonne Nouvelle University

(Q1) 1/5 | (Q2) 0/5

Biden’s election opens a window of opportunity to adapt the transatlantic relation to the new global context, under favorable conditions. Trump turned this relation upside down by pointing fingers at the EU as an enemy, something no American President had ever done before. Above all, he raised the awareness of Europeans about the deep political evolution on the other side of the Atlantic: before Trump, European stances on strategic autonomy diverged according to their heterogeneous analyses of the US. Trump led to a convergence. The EU intends to become a geopolitical actor and protect its strategic interests. With respect to the transatlantic relation, this requires protection against the US internal political division and the resulting radicalization, as well as the consequences of this internal situation on its foreign policy. Trumpism emanates from deep-seated changes, it has left its mark and could return to power in four years. There are still numerous aspects of the transatlantic relation that can be enhanced for the benefits of all, but it would certainly be pointless to dedicate time, energy, and political capital on some others.

The novel European awareness makes this question irrelevant. Modernizing the transatlantic relation requires identifying and accepting, as Europeans, the convergence and divergence of interest on both sides of the Atlantic. This notably applies to China, where we have different objectives. For the US, it is a matter of hegemony; whereas Europeans do not have global hegemonic claims. For Europeans, China raises questions about principles and norms (such as international law), and about economic choices past and present. This matter should also be a concern regarding digital and commercial challenges. On certain issues like climate or the pandemic, Biden’s election is clearly a new opportunity. In any case, a new American administration who believes in multilateralism and international cooperation, prioritizes global threats, condemns political repression while promoting democracy should be considered an opportunity for Europeans.

Jacob Kirkegaard

Senior fellow, German Marshall Fund of the United States

(Q1) 1/5 | (Q2) 0/5

I vote for a 1, i.e. limited risk to European strategic autonomy (ESA). The need for Europe to pursue ESA origins in the collapse of the post-war US consensus over its role and commitments in the global economic and political system. One of America’s two parties, the GOP, remain largely beholden to Trumpist notions of America First, trade protectionism and limited commitment to US treaty commitments. This platform, despite Biden’s victory, received the second highest public vote ever for any US presidential candidate and looks set to continue to dominate political thinking inside the GOP. The pursuit of ESA is hence warranted, as the traditional transatlantic community of values is now limited to one party in Washington, which is not a credible foundation for Europe to rest its security on. Biden’s victory doesn’t change this, though it makes it easier as ESA can now be pursued generally in collaboration with Washington, not locked in conflict.

ESA is required because it now matters which party wins the US presidency, not so who actually won. Biden’s election will make it easier to pursue, but that is not the most important issue. It is the longer-term undermining of bipartisan support for the traditional US foreign policy position – hard to imagine that there used to be a time when partisan politics stopped at the US shore – that necessitates ESA, not who actually wins the White House.

Hans Kribbe

Author of « The Strongmen: European Encounters with Sovereign Power » (Agenda Publishing, 2020)

(Q1) 1/5 | (Q2) 1/5

Why strategic autonomy? In the last four years, it took just two words and three syllables for autonomy advocates to answer that question: Donald Trump. End of discussion. In the next few years, answers may take longer, but they will be no less compelling.

By all accounts, Joe Biden is a profoundly decent and sensible man with his heart in the right place. His view of the United States and his own role as President is traditional, that of the world’s benign, liberal hegemon, the Leader of the Free World. Why, then, should Europe still want to emancipate itself as a sovereign power?

The answer to that question no longer sits in the Oval Office. It no longer has a blog on Twitter. Instead, it is found elsewhere, in tectonic and structural shifts that are inexorably pushing America and the world in new directions, in the changes that prompted Obama’s “Asian pivot” well before Trump, in China’s rise as a superpower, and in the storming of the Capitol in Washington more recently.

Biden promises a renaissance of the West. But so far in foreign policy we have hardly seen a rupture with the Trump era. Why not? Import restrictions on European steel and aluminium, popular with US steel workers, remain in place. So do US sanctions targeted at Berlin’s pipeline project Nord Stream. Trump’s China policy is backed by both US political parties. The WTO remains in gridlock, thanks to Washington.

Trump’s ghost lingers but will soon vanish, optimists say. Then all will be fine. More likely, four years of Biden will teach us that many of Trump’s policies have ghosts of their own, perfectly capable of surviving without him.

Charles Kupchan

Senior fellow at the Council on Foreign Relations (CFR), professor of international affairs at Georgetown University

(Q1) 4/5 | (Q2) 1/5

Had Trump been reelected, Europeans would have legitimately questioned the reliability of their American partner and become increasingly uncomfortable with their traditional dependence on the transatlantic relationship to ensure their security and advance global governance. Biden’s arrival in the Oval Office restores a significant measure of confidence in America’s commitment to collective defense and multilateralism. Most Europeans are breathing a sigh of relief, easing the political momentum that had been building behind the push for so-called strategic autonomy. Europe should continue its efforts to become more militarily capable, but the term “strategic autonomy” is unhelpful and misleading. For sure, Europe should be prepared to act on its own if necessary, but transatlantic teamwork should be the option of first resort. The stronger Europe becomes geopolitically, the better partner it will be for the United States. More Europe will fortify, not weaken, the transatlantic bond. Giving Europe more geopolitical heft is a long-term project; under the best of circumstances, the process will slowly move forward. In the meantime, Europeans and Americans should immediately begin efforts to map out a common strategy toward Russia and China. Transatlantic partners should also work together toward domestic renewal, discussing the kinds of investments and policy choices needed to revitalize political life within, and solidarity among, the Atlantic democracies.

Elena Lazarou

Analyst, European Parliamentary Research Service (EPRS)

(Q1) 2/5 | (Q2) 0,5

The move towards European strategic autonomy has been intensified due to transformations in the geopolitical, geotechnological and geoeconomic environment. Trump was a manifestation of these changes, but he was not the root cause. Thus, the change of guard in the White House is not as big of a risk to EU strategic autonomy as it is sometimes made out to be since these wider conditions remain unchanged. The debate should not be framed in binary terms but rather in qualitative ones: a Biden presidency opens up a wider door for strategic autonomy within a special partnership. For the most part, strengthening the EU’s ability to act autonomously eg. through new financing (NDICI) or peacekeeping capacity, is seen positively by the US. Similarly, major objectives of the EU’s global ambition – on climate, multilateralism and human rights – are fronts on which a stronger EU and Biden’s US will work side by side.

In defence, progress in EU-NATO cooperation and in third country participation in the EU’s defence plans, coupled with renewed trust, could smooth out tensions surrounding the misguided narrative of the EU “going at it alone and separately”. Biden’s commitment to Article 5 can be seen as a valid reason to strengthen the EU flank in NATO, making it an even more valuable ally, rather than as a reason to backtrack on strategic autonomy. Reconciling the EU ambition for digital sovereignty and industrial/trade aspects of open strategic autonomy with a reinvigorated transatlantic relationship will perhaps be the biggest challenge. But, indications that the new administration will rejoin discussions on a global digital tax, as well as shared concerns about supply chains and China (albeit framed differently) could lead to convergence rather than divergence. It is still early days, but labelling the Biden election as a risk for EU strategic autonomy is a risk in itself.

Bruno Maçães

Former Europe Minister of Portugal, Author of « The Dawn of Eurasia », (Penguin, 2018)

(Q1) 2/5 | (Q2) 3/5

The transatlantic relationship will be marked by China. The EU wants to make it very clear that it intends to have an autonomous China policy. This is not about whether that policy will be hawkish or dovish. It is about autonomy, about not being led by Washington on how to deal with the China challenge. The logic is eminently plausible, but it remains to be seen whether the Biden administration can fully understand it. The second important file will be technology. Europe is making a desperate bid to remain a major player in the technological field. The stakes are very high and we need a constructive approach from the Biden administration. Also here it is important that Washington understands what is meant by strategic autonomy. Europe cannot become dependent on technology produced elsewhere, even in the United States.

Giovanna de Maio

Nonresident Fellow, Foreign Policy, Center on the United States and Europe, Brookings

(Q1) 1/5 | (Q2) 2/5

“European strategic autonomy” is still a vague concept. Indeed, although EU member states have enhanced their defense cooperation through several projects under the PESCO umbrella, they are far from having a unified European command capable of performing military capabilities independently. Most importantly, member states do not share the same security culture nor perception of threats. As for the impact of Biden’s presidency, his administration does not represent “a risk” or a threat to European security ambitions. Quite the contrary. Given the domestic pressure on ending the endless wars, Biden and his team understand that it is in the US’ interest to empower allies in order to safely disengage from areas that are no longer considered a crucial security threat to the US but indeed impact international security. In this regard, it is likely that Biden will push for a division of labor within NATO, as he has already repeatedly mentioned the importance of increasing the alliance’s military deterrence vis-à-vis challenges posed by China and Russia. To do so there is no other way than increasing European military and defense capabilities. If Europe and the US interact in those terms, Washington will have little interest in discouraging European’s attempts to foster defense cooperation. Increasing transatlantic security and deterrence vis-à-vis China and Russia will be at the top of the transatlantic agenda together with managing the pandemic and addressing climate change.

Claudia Major

Senior Associate, German Institute for International and Security Affairs (Stiftung Wissenschaft und Politik)

(Q1) 1/5 | (Q2) 1/5

The Biden presidency is not a threat to European strategic autonomy in security and defense. The biggest risk is still to be found in Europeans themselves: by allowing themselves to be torn by division, by indulging into debates about sens and wording (European strategic autonomy, sovereignty, responsibility, good or bad) rather than concentrating political energy on implementation: agreeing upon political priorities, joining forces, and developing the necessary capabilities.

There is no single European reaction to Biden, but many. Central and Eastern Europeans, and the UK, fear to get less US attention for their worries and wishes, dread to see their special relationship suffer and to have to accommodate their European partners again. Others, like France, fear that the current enthusiasm naively oversees the shifting US priorities and the changing world order and that it breaks the momentum for European autonomy. And then there is Germany, likely to be the new transatlantic go-to partner in a Biden administration, which will let rise jealousy. Europeans need to resist the temptation of a divisive beauty contest to be Biden’s prime partner and should cooperate to increase their joint capacity to act.

The second question asked in this paper wrongly implies that a well-functioning transatlantic relationship would be a risk to a European capacity to act. Yet increased European autonomy is not only compatible with a stronger transatlantic bond – it is its precondition. Only a more capable (read autonomous) Europe can be a meaningful partner for a Biden government: to jointly shape global order, from regulating technologies to dealing with autocracies, and to defend a multilateral rule-based world order.

Laurence Nardon

Researcher, director of the United States programme at the French Institute of International Relations (IFRI)

(Q1) 3/5 | (Q2) 3/5

With a return to multilateralism and the will to mend America’s moral compass (democracy, human rights, freedom), the Biden Administration can only be constructive for Europeans. Antony Bliken – the new Secretary of State (who spent half of his childhood in Paris), Jake Sullivan – the National Security Advisor (Rhodes Scholard at Oxford) and Advisor Julie Smith (who holds strong connections with Germany) will most certainly restore links with European chanceries. They might probably take an “Obamian” stance on the European project, which considers a strong European Union as a valuable asset for the United States (unlike Trump for whom this supranational project was unbearable).

Some Euro-pessimists are concerned that the American friendship will incite EU actors to disengage from European strategic autonomy. They must rest assured that the United States will continue serving its own national interest and will not make things easy for European, especially regarding upcoming controversial issues such as trade, the GAFA tax or the protection and development of technology vis-à-vis China…

Above all, the Biden administration cannot rewind to 2016. The principle of free trade and military interventionism are now widely questioned in Washington, on both ends of the political spectrum. The United States will remain a friendly partner, but at a distance.

Kristi Raik

Director, Estonian Foreign Policy Institute of the International Centre for Defence and Security

(Q1) 1/5 | (Q2) 0/5

Joe Biden’s presidency is an opportunity to strengthen European and Transatlantic consensus on European strategic autonomy. The idea of European strategic autonomy was never going to generate consensus in the EU if defined as a distanciation from the US. Even in the event of a second term of Donald Trump, which luckily for the transatlantic alliance and global stability did not come about, few European countries would have reassessed the importance of the US for their security. In Eastern and Northern parts of the EU, a strong commitment of the US remains indispensable to contain the increasingly authoritarian and unstable Russia. At the same time, countries that worry most about Russia tend to take the need to strengthen their national defence capabilities seriously.

In a world of tightening great power competition and erosion of a rules-based order, Europe and the US need each other. Joe Biden’s election serves to reaffirm that the US and Europe share the same values and many similar interests in global politics. Europe must strengthen its capacity to act and ability to take care of its own security, but it is not ready to do it alone and should not aim at doing it alone.

Andrei Tarnea

Romanian diplomat, director general for communication and public diplomacy, Ministry of Foreign Affairs

(Q1) 1/5 | (Q2) 0/5

The new US administration’s approach will undoubtedly reduce some of the risks of transatlantic decoupling. This alone is not a sufficient reason to renounce the need for an actual EU strategic capability.

European strategic autonomy cannot be achieved simply as an alternative to the role which the US currently plays in security and strategic matters in our hemisphere. Neither will it come about as a result of the shifting dynamic of the transatlantic relations or due to the changing priorities in Washington. If it is ever to come about, it will be because of a shared European perception of strategic imperatives and a common will to jointly bear the cost of addressing them. Europe’s agenda is not that different compared to the US (climate change, nuclear security, terrorism, digital and AI revolution, addressing challengers like Russia and China etc), its means of achieving results are.

Strategic autonomy needs to have a wider and a more articulated set of objectives, means, and underlying values that an “alternative to the US”. To be frank, strategic autonomy has huge obstacles and significant political costs. To be able to justify those, Europe needs a credible and largely supported narrative of European exceptionalism akin to the one that underpinned the popular support for US foreign and security policy for many decades. This will necessarily be rooted in the concept of Europe as a normative power that respects and promotes its values at home and abroad. Its litmus test domestically will be the treatment of illiberal populist politics, externally it will be the security and stability of its eastern and southern neighbourhoods.

Bruno Tertrais

Deputy Director, The Foundation for Strategic Research

(Q1) 3/5 | (Q2) 2/5

Biden’s administration should probably see the idea of Europe taking more responsibility for its own destiny as a good thing. In the meantime, its willingness to “repair alliances” and “re-engage the United States” could be at ill with the idea of “European sovereignty.” The way in which the United States will address European strategic autonomy will not look so different from the Clinton Administration. At the time, it was our own doubts regarding the reliability of American involvement, especially in the Balkans, that led Paris to start advocating for the concept. Our disagreements about European dependence on the American defence industry, or on the extraterritoriality of the American law were already strong at that time.There are, however, some notable differences nowadays, starting with what is known across the Atlantic as the return of competition between major powers.

Russia and China represent much greater challenges today than they did at the time – which reinforces the arguments for enhanced Western cohesion. As for institutions, their enlargement to the East has undoubtedly led to a stronger transatlantic bias. These elements will not strengthen, in Europe at least, the credibility of the traditional French narrative which had regained strength under Obama and Trump, pointing out America’s ditherings in Europeand its growing interest for Asia which, in turn, is beneficial for greater European autonomy. Finally, I do not really believe in the idea that the US will increasingly allow for Europe to be in charge of the MENA region’s security. It is a region incoming American presidents should always be warned about in the following terms: you might not be interested in the Middle-East but the Middle-East will always be interested in you.

Nathalie Tocci

Director of the Istituto Affari Internazionali (IAI), Special Advisor to EU High Representative and Vice President of the Commission Josep Borrell, Rome

(Q1) 2/5 | (Q2) 3/5

President Biden in and of himself does not represent a risk in the pursuit of European strategic autonomy. The risk is posed by Europeans, and Europeans alone, and their reluctance to tackle hard questions in order to walk the talk, rather than just talk about this goal. Such practice requires that Europeans reinforce their internal cohesion, resilience and strength and take greater risk and responsibility externally to reduce asymmetric dependences that can be exploited to our disadvantage. However, to the extent that a friend in the White House reawakens European instincts for inaction, the Biden administration could indirectly and inadvertently increase such risk. It would be tragic if Europeans were to fall in this trap and, rather than fully reap the gains of a revamped transatlantic bond, they were to hide behind it in order to shy away from their own responsibilities. Were this to happen, we would only have ourselves to blame.

Pierre Vimont

Senior fellow, Carnegie Europe

(Q1) 3,5 | (Q2) 2/5

One is more assertive when faced with adversity rather than among friends. Trump, at least, had the merit of raising Europe’s awareness regarding its fragility and compelled it to react. Armed with a firm ambition to erase Donald Trump’s legacy, the new Biden administration is both reassuring Europeans and paving the way towards a “return to normal”. Although European nations might have to take on a greater share of the transatlantic defence burden, there will be a strong incentive to rely on a partnership largely based on the American vision of the world. With this risk in mind, avoiding an over-simplistic alignment will certainly not be enough for Europeans to acquire a new sovereignty. If Europe truly wants to build a serious “strategic autonomy”, it will have to think far beyond its relationship with the United States. To reach a real geopolitical ambition, Europe will have to develop its own strategic vision and translate it into operational objectives and concrete capability to meet the challenges of our time. This is a much more difficult endeavour than the search for a more balanced relationship with its American ally.

Notes

citer l'article

Rosa Balfour, Emil Brix, Maria Demertzis, Michel Duclos, Maya Kandel, Jacob Kirkegaard, Hans Kribbe, Charles Kupchan, Elena Lazarou, European Strategic Autonomy and the Biden Presidency, Giovanna de Maio, Claudia Major, Laurence Nardon, Kristi Raik, Andrei Tarnea, Bruno Tertrais, Nathalie Tocci, Pierre Vimont, European Strategic Autonomy and the Biden Presidency, Feb 2021,